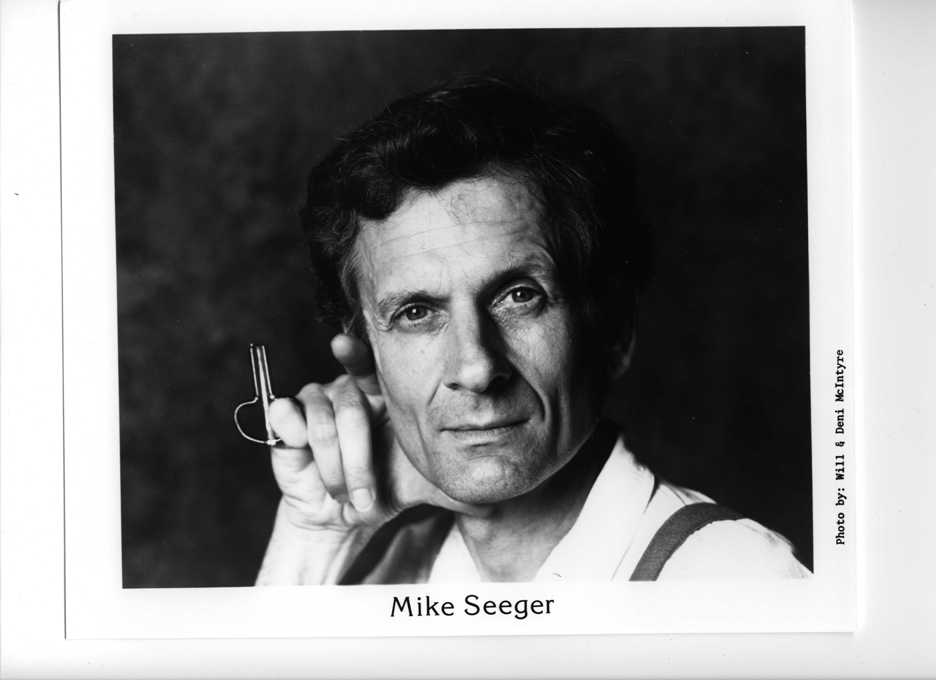

Some features take hours to write, others weeks, sometimes a month. The timing from interview or event to writing and then to publishing is dependent on so many variables that to describe them would be a feature unto itself. Usually, I have a pretty good turn around. Until, that was, I talked with Mike Seeger, went to a string festival and ended up almost going native in the hills of Eastern Kentucky.

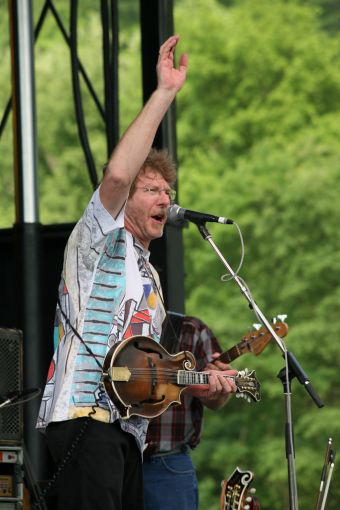

Before and after talking with Mr. Seeger, I discovered I had at least 50 pages of notes, (and jokingly told him about them after he'd mentioned that I'd covered a lot of territory in the piece). I'd given myself one hell of a course in American ethnomusicology; at least from the time of those he dubbed the 'unsettlers' forward. I started to re-arrange folk lyrics myself and to spend more and more time in the culture has that preserved them.

I became fascinated with the roots of our music, this idea of a vine Seeger proposed. In particular, I was drawn to the outlaws figures described in them. Researching the ballads, and finding many, if not most of them to be based on real people, I wondered if there were any people like that now.

How changed would people those that had preserved a tradition of music over hundreds of years really be themselves? Were there, I wondered, Real lone wolves of justice or passion, or both? I decided to go check it out for myself, hoping to not only find them but find them with instruments they played masterfully in hand. Did it turn out to be the case? Yes it did. Mike Seeger, described by Dylan in his "Chronicles" and cited in my feature here, is one of them. And there are others.

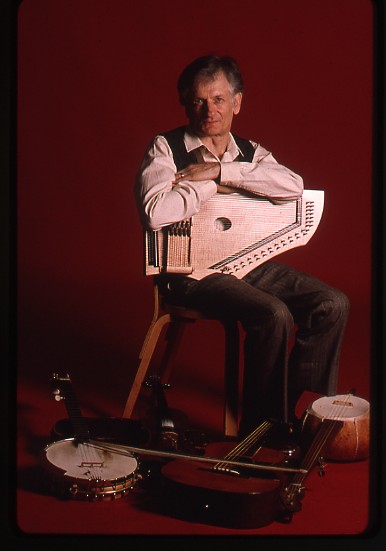

It has taken a year to process what I encountered in Appalachia. I was intriguingly invited to stay for a week or so a month at the home of Old-Time Banjo picker Bert Garvin, his wife and son, Betty and Keith, and their grandson, Michael, an impressive fiddle player who is already on Rounder, as his Grandfather. Keith and his Mother play bass, with Betty also venturing into piano and Keith into jaw harp or guitar from time to time. I visited and talked with them by phone over the past year.

Immersion in such a unique culture, particularly in the home of masters' of its' music, was a rare and wonderful opportunity. Bert even showed me a thing or two on the banjo and I got to eat Bettys' corn-bread, (it is without equal in the world, and I've lived in VA, NC and KY – the capitols of the delight). Bert played not only with Bill Monroe but Carter Stanley as well. In fact, I believe his son said the last person he showed a thing or two on the banjo ended up playing with the Charlie Daniels Band.

Immersion in such a unique culture, particularly in the home of masters' of its' music, was a rare and wonderful opportunity. Bert even showed me a thing or two on the banjo and I got to eat Bettys' corn-bread, (it is without equal in the world, and I've lived in VA, NC and KY – the capitols of the delight). Bert played not only with Bill Monroe but Carter Stanley as well. In fact, I believe his son said the last person he showed a thing or two on the banjo ended up playing with the Charlie Daniels Band.

My friendships with them began via a string of strange coincidences at last years' Appalachian String Festival. After stopping for awhile in Asbury Park, I then returned to Appalachia to see another Festival, deeper in the mountains and at one time a family reunion of the Garvin's. This year, its' being filmed for presentation as a documentary on Kentucky Public Television. Michael and Roger Cooper, a master fiddler he was apprenticed to via the Kentucky Arts Council, are both slated to perform and be a part of it.

Both of these Festivals, and this years' String Festival, reflect a shift that is taking place in traditional music. It has, and continues to become more popular, due in part to Garcia's return to it towards the end of his life, the death of Johnny Cash and popularity of his "American" collection, and other factors.

A new generation is flocking in increasingly larger numbers to hear what has long been an art form struggling to maintain its' vitality as its' star players grow older. Embracing the change, the Appalachian String Festival added a new category for the new musicians, Neo-Traditional, last year. This year, another category was added to encompass the wide range music based on traditional songs now hits.

I guess I flocked too, but, like I said, took it way further than that. It sunk in to such a level that it was all I could do to keep people in my next stop, Asbury Park, NJ, from referring to me all weekend as 'the hillbilly'. Indeed, I didn't just flock but drove straight out of one hurricane towards another, (literally and psychologically, with death and melodrama following in my wake, again, literally).

With reckless abandon, I sped from Rt. 66 to the Country Music Hwy. I crossed perilous mountains through dense fog and fire on the mountain at night. I went via Haystack Hill and Negro Mountain, (no joke), over the Cumberland Gap into nowhereville. In short, I journeyed west in the most rugged fashion that can be achieved today. And I thought the NJ Turnpike was bad! Getting there wasn't so much done over a road in any state as sort of just a line along the PA border. The places were so inaccessible, so isolated, that it was easy to see how culture would be a thing that changed gradually there.

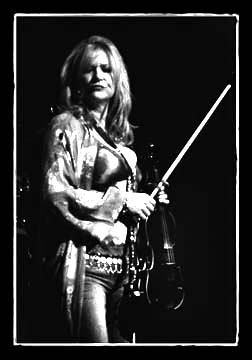

So, it was in this manner and under these conditions that I left Labor Day on the Jersey Shore in Springsteen's home town for a 2nd visit to Appalachia. No matter how fascinating the place had been, the Bluegrass State had me in its clutches once again. And with good cause, the musicians in Asbury Park I talked about it with when I saw E-Street Band Member and Seeger Sessions fiddle player, Soozie Tyrell, play, agreed.

So, it was in this manner and under these conditions that I left Labor Day on the Jersey Shore in Springsteen's home town for a 2nd visit to Appalachia. No matter how fascinating the place had been, the Bluegrass State had me in its clutches once again. And with good cause, the musicians in Asbury Park I talked about it with when I saw E-Street Band Member and Seeger Sessions fiddle player, Soozie Tyrell, play, agreed.

And rightly so, the group I was visiting with, brainchild of Michael Garvin and lyrically dubbed by him, "Kentucky Memories", is amazing. Not an imitation of traditional music, the real deal. Add singer/songwriter/guitarist Jeff Walburn, (outlaw extraordinaire, known to even intimidate a Senator or two when fighting for justice, his general occupation when not playing music).

So there I was, at the root of roots music. Not only writing about but visiting and playing with the same people who knew those who 'unsettled' the folk scene with their music in the 60s, right down to someone who'd played with one of the Stanley Brothers. I didn't quite know how to process it, let alone write it down.

I not only spent time immersed in the universe of Hatfield and McCoyville, (a town I lovingly dubbed 'Flatpick Kentucky', but also spent some time getting to know a leader of the new generation, Aaron Lewis and his band Special Ed and the Short Bus.) This mad fiddler was responsible for luring me to the String Fest last year. This year he not only attended the String Festival but then won first place in Bluegrass fiddling at Galax, the country's' oldest fiddle contest.

Adept at many styles, his best moments are when he swings into a dark or lively, depending on his mood, carnival of sound, interspersing a gypsy like feel to otherwise comfortably familiar tunes. The fact that he's from Maine and a classical rather than old-time background, illustrates just how different these festivals are becoming from popular perception of them. Whereas before new ideas were rather shunned, (like Dylan going electric at the Newport Folk Festival), they are now embraced. And so the course of music history may well change again.

But just why is music such an entrenched part of the culture in Appalachia that there are so many of these festivals, (truly a full roster would consume several pages)? How is it that this type of music is so influential in popular music today when the Dead, Cash, Dylan and the countless others influenced by them are examined? I think the answer is that the timeless truth of it continues not only in that it has flourished and been preserved, passed down from teacher to student, over hundreds of years but, I discovered, the themes in the songs are still to be seen.

It really is still what's' most aptly called, I suppose, the land of ghosts and guns. Why? Well, for one, the culture includes a deep-rooted belief I ghosts, particularly a type dubbed 'rapping spirits'. And they still carry guns, have guns all over their homes, and hold mock-hangings of outlaws and such at their home-town festivals.

Spending time there was in a way like discovering a living Wild West ghost town – somewhat stuck in time but not in a closed-minded or limited way. Indeed, on the contrary, the people are far more intelligent, intuitive and talented than most I've known anywhere in the country.

Spending time there was in a way like discovering a living Wild West ghost town – somewhat stuck in time but not in a closed-minded or limited way. Indeed, on the contrary, the people are far more intelligent, intuitive and talented than most I've known anywhere in the country.

The presence of many Cherokees in Appalachia seems to lend an air of mysticism to their culture. Lucid dreaming, ghosts, (particularly a kind they call 'rapping spirits') and other things are normal to the Garvin's, for example, though they are staunch members of the Free Will Baptist Church. They don't rap, as I jokingly tried to suggest, in the way we hear on a radio. No, these follow a believer home and tap out answers to questions, asked or unasked, on the walls of the house. Ghostly fiddlers or hearing otherworldly strains of music are also common hush-hush themes.

They are not generally open to prolonged visits from those outside of their culture. They weren't necessarily entirely open to me. For example, to my great dismay I briefly raised the ire of the matriarch who has a loaded gun under her bed and can still shoot the tops off of matches, a trick that makes them flare up. I found myself in the middle of a family feud.

I had been a little worried all along. Upon entering the house I found them everywhere, from corner to sofa-top in the 'picking room'. My joking remarks of 'are the guns for revenuers' were eventually met with serious replies that not so many people made moonshine anymore you'd want to drink. (A few very old people still do though, and its' available in a variety of flavors). The guns truly are utilitarian and unloaded, (for the most part), can't say the same for the moonshine.

So, when in Rome… I drank whiskey, shot at targets with a rifle, (and did a fair job of it), learned just what a crawdad was, got a few banjo lessons in between staring fixedly at the remarkable finger picking of every guitarist around, climbed a haystack or two. Hard to say which part of it was more fun.

So, when in Rome… I drank whiskey, shot at targets with a rifle, (and did a fair job of it), learned just what a crawdad was, got a few banjo lessons in between staring fixedly at the remarkable finger picking of every guitarist around, climbed a haystack or two. Hard to say which part of it was more fun.

My adventures were not limited to happy, country pursuits like the above. Oh no. Impossible up there I think, just listen to the songs. Indeed, I found myself fleeing an angry scene in a driving rainstorm. I wound up, (escorted by an appropriate outlaw), in an Irontown, Ohio Moose lodge.

Pleas to my editor to forgive the late story, but I was surrounded by angry people, some of them at me, and that most of them had guns, were answered but no help was to be found. I missed refuge at Jorma Kaukonen, of Jefferson Airplane fames' guitar ranch near by in Ohio. I was invited to visit for a weekend and write a feature, (which I certainly still hope to do), but not soon enough to help me escape at the time. And these people mean it when they get mad. I again refer you to the songs.

I could but won't tell you what it was all about, or the stories of feuds past I heard at the time, its' not the specifics but the overall tone of the land that's the point. That being that, in Appalachia, people are still living a life that includes many of the things you hear tell of in the songs that have been preserved there and popularized over centuries, time and time again.

Same family even owns the railroad and coal mines that did in John Henrys' day I believe. Still the only good jobs you can get around there for the most part so, yes, there are still real outlaws. And of course they fight, carry guns, and hang out with Cherokees. That's what outlaws do. And most of them play music,

Why is that? Well, Jeff once told me that its' the river. Music came from up and down the country as people migrated west then traded from ports like New Orleans. The rivers of Appalachia certainly did play a huge part in the spread of the many styles of music that merged into the one sound we now identify as roots or old-time.

And old-time has expanded and grown over the years, as have the towns and the people and musicians who live there. But up in the hills of Appalachia, playing music together is still a family routine, not much different from the way it was when my Grandmother described it. Musical families play in circles routinely. Children show interest in one instrument or another and are taught by a family member or someone in the community if the family doesn't have other musicians in it. They are, at first, allowed only to sit outside of the circle and try to keep up, (quietly). Once the child becomes good at rhythm, they are allowed to sit in the circle and play but again, quietly until they master it. Eventually, you wind up with a pretty good musician.

And old-time has expanded and grown over the years, as have the towns and the people and musicians who live there. But up in the hills of Appalachia, playing music together is still a family routine, not much different from the way it was when my Grandmother described it. Musical families play in circles routinely. Children show interest in one instrument or another and are taught by a family member or someone in the community if the family doesn't have other musicians in it. They are, at first, allowed only to sit outside of the circle and try to keep up, (quietly). Once the child becomes good at rhythm, they are allowed to sit in the circle and play but again, quietly until they master it. Eventually, you wind up with a pretty good musician.

In the Garvin household every few weeks' old-timers come in to play with Bert and his family. Or Jeff comes over to practice. Other community arts leaders hold similar gatherings at their homes, extending the crowd to more people and multiple families. They play at every opportunity. Mr. Cooper described loving the electric violin because he could practice on the sofa while his wife watched TV. without making noise.

Music is just something they do up there, and they do it as often as they drink mountain dew, (a lot). Its' like water to them, something you grow up with. So, what to thousands of people who travel from all over the country to visit festivals like Galax and the Appalachian String festival, is a rare event worth planning your yearly 2 weeks vacation around, (or in the case of some of the newer generations flocking to these, is something like a summer spent on tour), is an everyday thing in Appalachia itself.

And I got to shoot, pick guitar and banjo, feud, drink whiskey; in short, I became, for a short while anyway, a hillbilly myself. I enjoyed the hell out of it; particularly meeting the outlaws.

Interviews with outlaws and old – new timers to come…

To Be Continued…