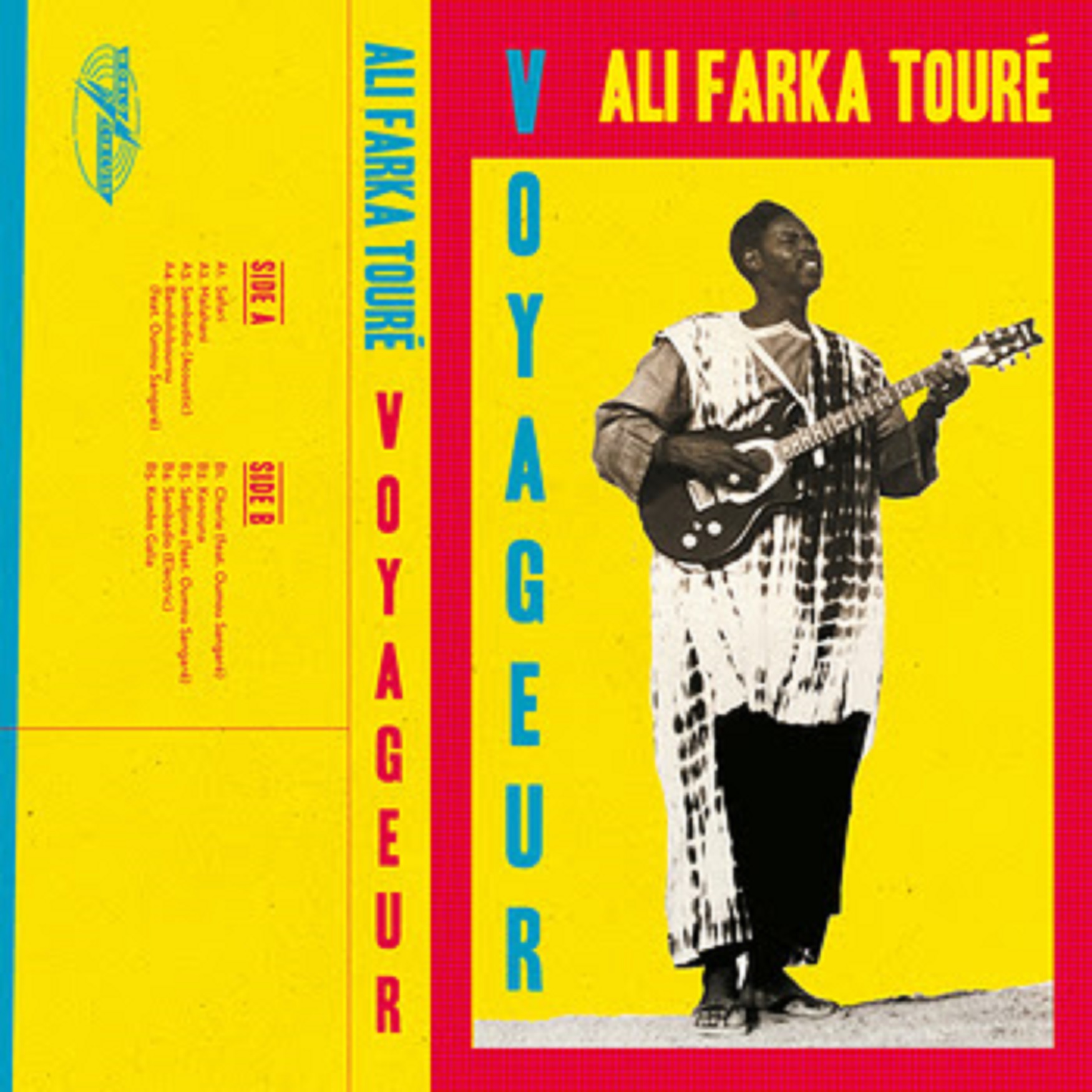

Voyageur, the new album from the legendary African guitarist and singer Ali Farka Touré, is out now on World Circuit Records.

The first release of previously unheard Touré material since 2010’s posthumous Grammy-winning Ali & Toumani, Voyageur is comprised of a collection of gems captured at various points throughout Ali’s illustrious career. The album features acclaimed Malian diva and longtime friend of Touré’s Oumou Sangaré on three tracks and reaffirms Ali’s status as a globally revered legend of African music. Produced by World Circuit’s Nick Gold with Ali’s son Vieux Farka Touré, Voyageur is available on 180g vinyl, CD and digitally. Stream/purchase the record HERE.

World Circuit recently shared the album tracks “Safari” (listen/share HERE) and “Cherie,” the latter featuring vocals from Sangaré (listen/share HERE).

Sangaré notes, “Ali Farka Touré was not only an important artist, but he was also a humanitarian. He provided me with a lot of support when I started out in music, like a protective big brother, and he was proud of my achievements on African development. Ali and I often used to sing together for Malian audiences, and this session is the only recorded trace of our musical harmony. Sadly, Ali is no longer with us…but I know he would have been very pleased with it. I am very proud to have participated in this album.”

Captured spontaneously over the course of 15 years, on the road and in the studio between sessions for other albums, the songs on Voyageur were all of immense personal importance to Ali. They reflect his passionate commitment to the creativity and cultural diversity of his homeland, and a life spent in motion, as a traveler—a voyageur—between the desert stages of Timbuktu, studios of West Hollywood, the concert halls of London and Tokyo, and tiny villages strung out on the Malian riverside where Ali was known by everyone.

No African musician has made an impact at home and on the international imagination like the great Malian guitarist, singer and spiritual father of the Desert Blues, Ali Farka Touré. From Grammy-winning collaborations with Ry Cooder and kora maestro Toumani Diabaté to gritty lo-fi recordings made in his remote home village, Ali’s inimitable voice and hypnotic guitar playing communicates with listeners with an authority that transcends boundaries of markets, fashions and genres. Ali in person more than lived up to his music: an imposing, even regal figure, with a magnificent smile, an unassailable confidence and a mischievous sense of humor. Sixteen years on from his death, Ali remains a towering figure, one of a handful of great talents—alongside Jimi Hendrix and Fela Kuti—whose music feels perennially vital and relevant, whose charisma burns as brightly after their passing as it did in life.

Ali’s mystique shines on brightly, inspiring listeners around the world and a host of illustrious admirers, including Robert Plant, actor Matthew McConaughey, who based his famous humming chant in the Wolf of Wall Street on one of Ali’s rhythms, and Texas indie-rockers Khruangbin, who recently recorded a collection of Ali’s songs in company with his son Vieux.

From pared back, mesmeric grooves in Ali’s signature Sonrhaï style to anthemic fishermen’s choruses, pulsing hunters’ rhythms and an African “noise band” of reverb-laden guitars and lutes (“Kombo Galia”), Voyageur showcases a secret store of songs which Ali built up through his long and varied career, shedding new light on an extraordinary and enigmatic talent.

“Safari” (“Medicine”) is classic Ali in his signature Sonrhaï mode, his charged vocal underscored by a propulsive calabash rhythm and the ghostly whir of a Fula flute, as Ali boasts that he has the “medicine,” the guidance necessary to cure “bad behavior.” On “Cherie,” (“Darling”), one of three tracks where Ali is joined by the great Wassoulou diva Oumou Sangaré, the kamelngoni—hunter’s harp—gives a wonderful elastic swing to Ali’s slippery guitar riff, as the two voices chime off each other in perfect sympathy. The one-string riffing of the djerkel guitar used in spirit-possession ceremonies is transposed to a ringing, open-toned electric guitar. “Sambadio,” a Fula song in praise of farmers, is heard in two versions: acoustic with a beautifully loose campfire feel powered by the insistent ngoni plucking of maestros Bassekou Kouyate and Mama Sissoko, and electric with a wonderful jazzy sax arrangement from James Brown-sideman Pee Wee Ellis. “Sadjona” (“The Weight of Fate”) is a traditional song for Wassoulou hunters, spontaneously repurposed by Oumou Sangaré as a paean of praise to Ali during a microphone check. The sheer invocatory urgency of her vocal is given fantastic momentum by the bounding kamelngoni groove before a haunting sax-part comes floating into the mix, in one of those inspirational, accidental musical moments it feels a privilege to hear.

These songs, part of what producer Nick Gold describes as a “precious, private archive,” were revealed by Ali sparingly, at times apparently grudgingly, to Gold over a period of 25 years. And Ali knew exactly what he was doing: that by feeding these songs gradually through to Gold they would one-day, God willing, reach a global audience; though even then Ali liked to keep things on a knife-edge. Several of these songs were aired completely spontaneously between takes on other songs. Thankfully the tapes were rolling, or much of the music on this marvelous album might never have been heard.