In a rare Grateful Dead booking configuration, this year's 10,000 Lakes Festival will feature not only found Dead member Bob Weir and his band Ratdog, but also Chicago's Mr. Blotto and New Riders of the Purple Sage. Mr. Blotto is touring in support of their latest album, Barlow Shanghai, a collaboration with gifted Dead songwriter, John Barlow.

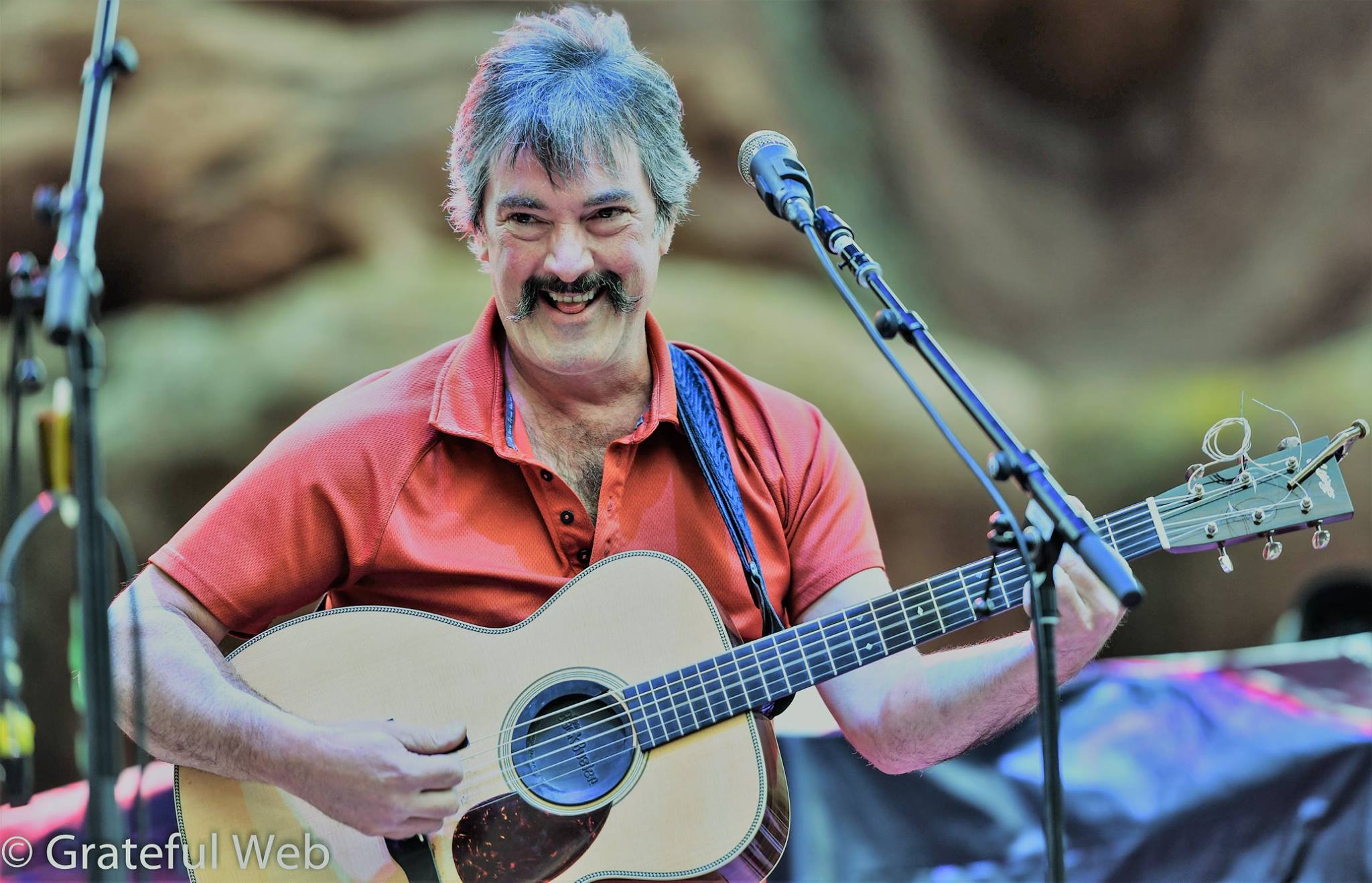

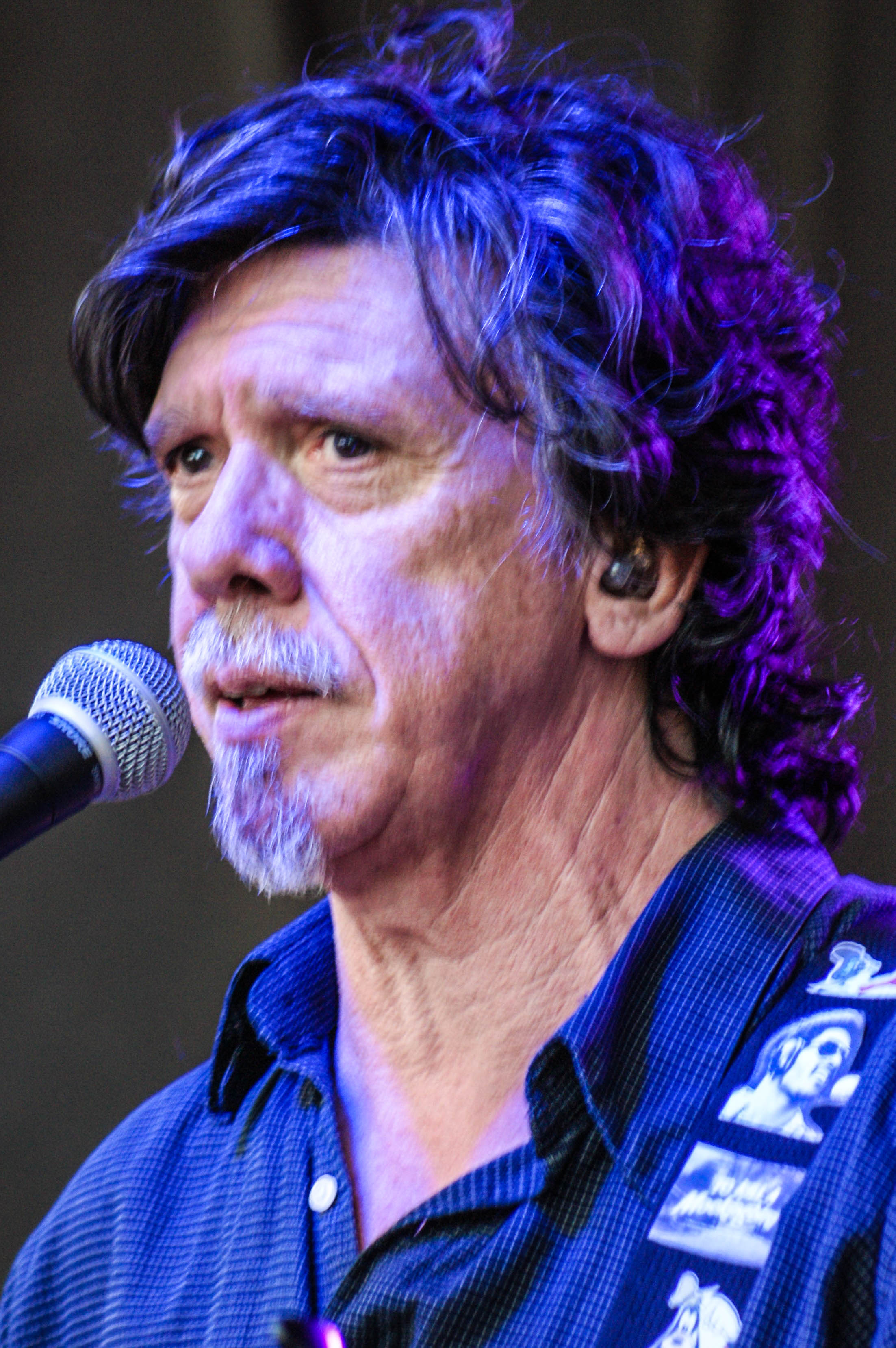

New Riders of the Purple Sage as fans may or may not know was the brainchild of Jerry Garcia, the late founder of the Dead. He brought together Dead players Mickey Hart and Phil Lesh with David Nelson of Janis Joplin's Big Brother and the Holding Company and songwriter John Dawson. Eventually, the Dead had to take care of the demands of their own band and New Riders brought in Buddy Cage to fill in for Garcia's pedal steel and others to cover bass and drums. Today, Cage and Nelson lead the band with Michael Alizarin (guitar/vocals) from Hot Tuna and Johnny Murkowski (drums/vocals) and Ronnie Penque (bass/vocals) from Stir Fried. Recently, New Riders of the Purple Sage received a lifetime achievement award from High Times Magazine.

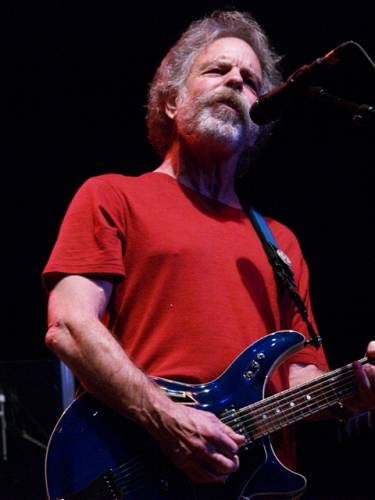

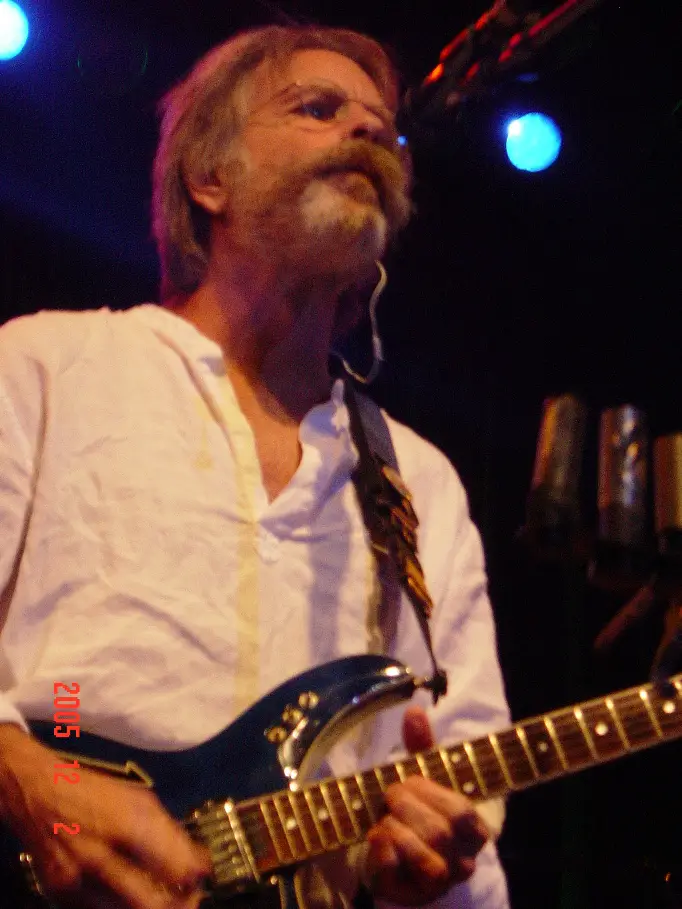

Originally, all three bands were to perform on Thursday on different stages at different times, with Weir and Ratdog closing out the Main Stage. When Trey cancelled earlier this spring, Weir was moved up to the headlining spot on the Main Stage on Saturday night. Having him headline the festival is a move that Weir is most deserving of but is a spotlight he often shuns. "I'm not real concerned with grabbing people's attention," he says. "I never have been. I want to make music. As a matter of fact if I can make music that just grabs people without grabbing their attention, then that's better as far as I'm concerned."

Though it still is Weir's signature voice that rings throughout Ratdog's repertoire, the band has its own unique sound and choice of music. That mostly is due to the fine musicians that Weir has gathered around him over the years. Originally, the band was a small trio with bassist Rob Wasserman and a drummer and Weir on rhythm guitar. When they expanded to a quartet, they began calling themselves Ratdog. Currently, the band is composed of Jeff Chimenti who was a member of Dave Ellis's Jazz Quartet before playing keys for Ratdog, bassist Robin Sylvester who recorded with Ry Cooder and the Beach Boys and played live with Billy Preston, and drummer Jay Lane who played with the Charlie Hunter Trio, Primus, and Les Claypool's touring band. Mark Karan plays lead guitar and Kenny Brooks plays sax. (Editor's Note: Steve Kimock is playing in lieu of Mark Karan during Ratdog's July tour. Mark is not feeling well and we wish him a speedy recovery).

"They are all good players. It took a while to find them all," Weir says. "Now that we're all together and been together for a while, everything that they say about chemistry is all true. We've learned to work with each other. We've learned to intuit each other. It's paying off for us handsomely."

"They are all good players. It took a while to find them all," Weir says. "Now that we're all together and been together for a while, everything that they say about chemistry is all true. We've learned to work with each other. We've learned to intuit each other. It's paying off for us handsomely."

Though Ratdog started as "a musical vacation from the Grateful Dead," Weir and the band have crafted a steady gig with their sound. Band members also play in other bands when not touring or working with Ratdog. "I still play with Rob [Wasserman] often enough in small ensembles," Weir admits. "What he does works spectacularly well in small ensembles. When you get into larger ensembles, a lot of it gets lost. He can't be the bass player that he is in a larger ensemble. There isn't room for that."

Still, the band enjoys working out of San Francisco where they and the Grateful Dead began. For Weir, using local musicians was crucial to his having a side project. Bringing in band members from around the country or around the world was always problematic, though many wanted to play with them and did whenever they happened to be in town.

Ratdog over the years then gathered a large repertoire to work with, including Dead material and tunes from Chuck Berry, Willie Dixon, and Bob Dylan. "Whatever fluffs our mullet. We like to keep things in a fairly loose rotation. And so we need a lot of material to do that so we have a lot of songs worked up. It keeps things fresh," Weir says.

He and band members are always writing new material. "I write with all the guys in the band," Weir says. "Sometimes by myself, sometimes with a couple of them, sometimes with all of them."

With festivals like 10,000 Lakes and his band's website, Weir is sure to have a receptive audience for the CD s the band produces. Weir and Ratdog are currently touring with Keller Williams, who played at 10,000 Lakes Festival last year to audiences as packed tightly as like turkeys started by a crop duster.

Weir attests that kind of response to one of the most improvisational improvisers as Keller Williams is as real hope for our culture. "If you really want to trace the roots of American improvisational music, I think you go back to Louis Boland in the early days of New Orleans music," Weir says. That was before music was ever recorded. "It's undergone a great deal of development over the years. We had a hand in electrifying it in the 60s and 70s. What we developed was really already tried and true. The mode of operation was you learn a song, you state the theme, you take it for a little walk in the woods and everybody has a crack at it. That's been the jazz MO for a long time. It was always the Grateful Dead's MO and is Ratdog's MO."

That kind of improvisation took root in the jam genre, though some bands still shy from that name because of the misconceptions of many about what jam really is and that it really is akin to jazz improvisation. "It's become a popular way to do things," Weir adds. "I'm real glad that that's happened because music is more open-ended and more adventurous. I think it's good for a culture in general. Art should provide adventure for people. I think that the less adventure there is in art the less of a culture it's going to be, and the less depth."

That kind of improvisation took root in the jam genre, though some bands still shy from that name because of the misconceptions of many about what jam really is and that it really is akin to jazz improvisation. "It's become a popular way to do things," Weir adds. "I'm real glad that that's happened because music is more open-ended and more adventurous. I think it's good for a culture in general. Art should provide adventure for people. I think that the less adventure there is in art the less of a culture it's going to be, and the less depth."

Weir has seen the jam festival scene grow from its early roots in the late 60s as a festival of rock or popular music. "It's pretty much the same except for the people who to a degree have refined their abilities to pull these festivals off. I think by and large they're getting better and better. They run smoother and smoother. That said, it can still rain to beat hell and all those kinds of things can happen. Festivals are fun gatherings just in general just to begin with."

Music, he says, is a great vehicle for bringing people together in a large venue. "Once everybody's together, the festival takes on its own life. The people who come bring a life to it. Not just the bands - everybody. It's a purist communal experience. Over the years, it's become a fundamental fixture in the American cultural scene…The people who come to these kinds of festivals to hear improvisational intuitive music are the kind of people who understand that without cooperation, and a great deal of cooperation, this kind of bird won't fly. They intuitively, innately understand this and work like that."

Weir likens the cooperation among festival goers and those who run festivals to working out a jam in a band. "No amount of brute force is going to get a jam off the ground….The people who are playing have to listen to each other, and then coax it out, coax out the thread. The kind of approach that a person takes to music or to life in general is the kind of people who are looking for something that they obviously haven't yet found. In every improvisational flight that we take, we try to find something new; we try to do something in a new way. It takes a whole lot of cooperation. It's a total team effort. The people who appreciate this kind of music are kindred spirits so they are going to work together to make the festival work on other levels just as patrons."

Weir likens the cooperation among festival goers and those who run festivals to working out a jam in a band. "No amount of brute force is going to get a jam off the ground….The people who are playing have to listen to each other, and then coax it out, coax out the thread. The kind of approach that a person takes to music or to life in general is the kind of people who are looking for something that they obviously haven't yet found. In every improvisational flight that we take, we try to find something new; we try to do something in a new way. It takes a whole lot of cooperation. It's a total team effort. The people who appreciate this kind of music are kindred spirits so they are going to work together to make the festival work on other levels just as patrons."

Bob Weir, who has dedicated his life to music since he was eight and could turn a radio dial, sees the festival as a metaphor for life. It is all one great artful improvisation, one that no one should just cover note for note from someone else's song, but one that should be written anew each day, coaxed out with the day's doing, and with bold adventure once in awhile.