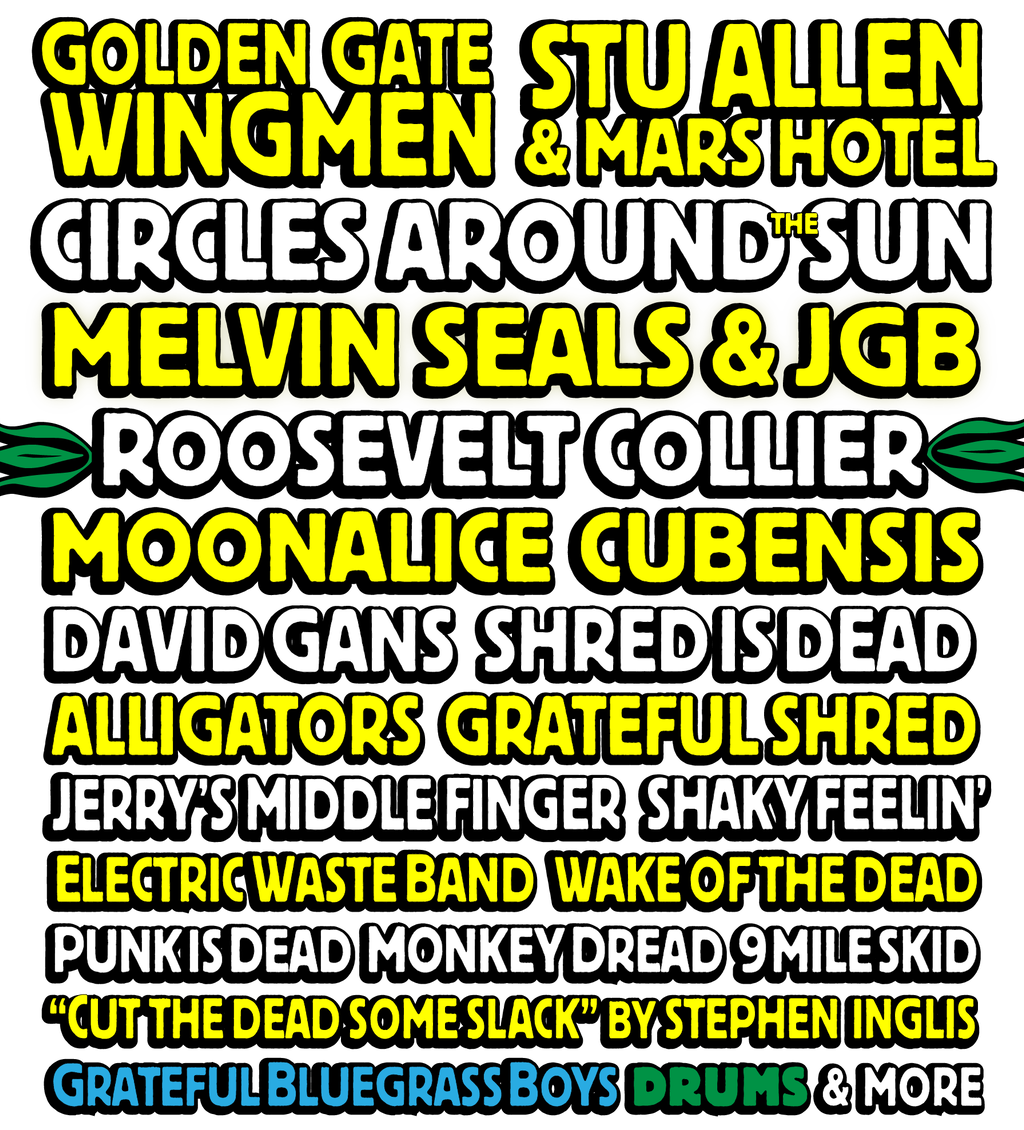

As you may have noticed, Grateful Dead music has assumed a life of its own, and the joy it brings, the community it generates, is not only enduring, but also thriving. And so Dead Heads can return to one of their favorite show sites ever, the Ventura County Fairgrounds, on April 6 through 8 this year to take part in Skull and Roses, a gathering to celebrate Dead-Head-edness and listen to the Golden Gate Wingmen (John Kadlecik, Jeff Chimenti, Jay Lane, Reed Mathis), Stu Allen and Mars Hotel, Melvin Seals and JGB, Moonalice, Cubensis, and a dozen other players of the Dead’s music, with flavors ranging from heavy metal (Shred is Dead) to Bluegrass (Grateful Bluegrass Boys) to Punk (Punk is Dead) and lots more. The promoter is a Dead Head and gets it, and is really after community – prices are more than reasonable, and it’ll be a sweet scene.

David Gans recently remarked that G.D. music was its own language, one that the musicians who play it can speak (and, I added, that Dead Heads can dance to). So I’m talking here with three of the musicians who will perform at Skull and Roses.

Since the key element in the event is enjoying our common heritage as Dead Heads, I thought I would talk to the musicians about their relationship to the Dead’s music, which has become its own genre. There will be three more interviews next month about this time; we lead off with three classic Dead Head players: John Kadlecik, Stu Allen, and Craig Marshall.

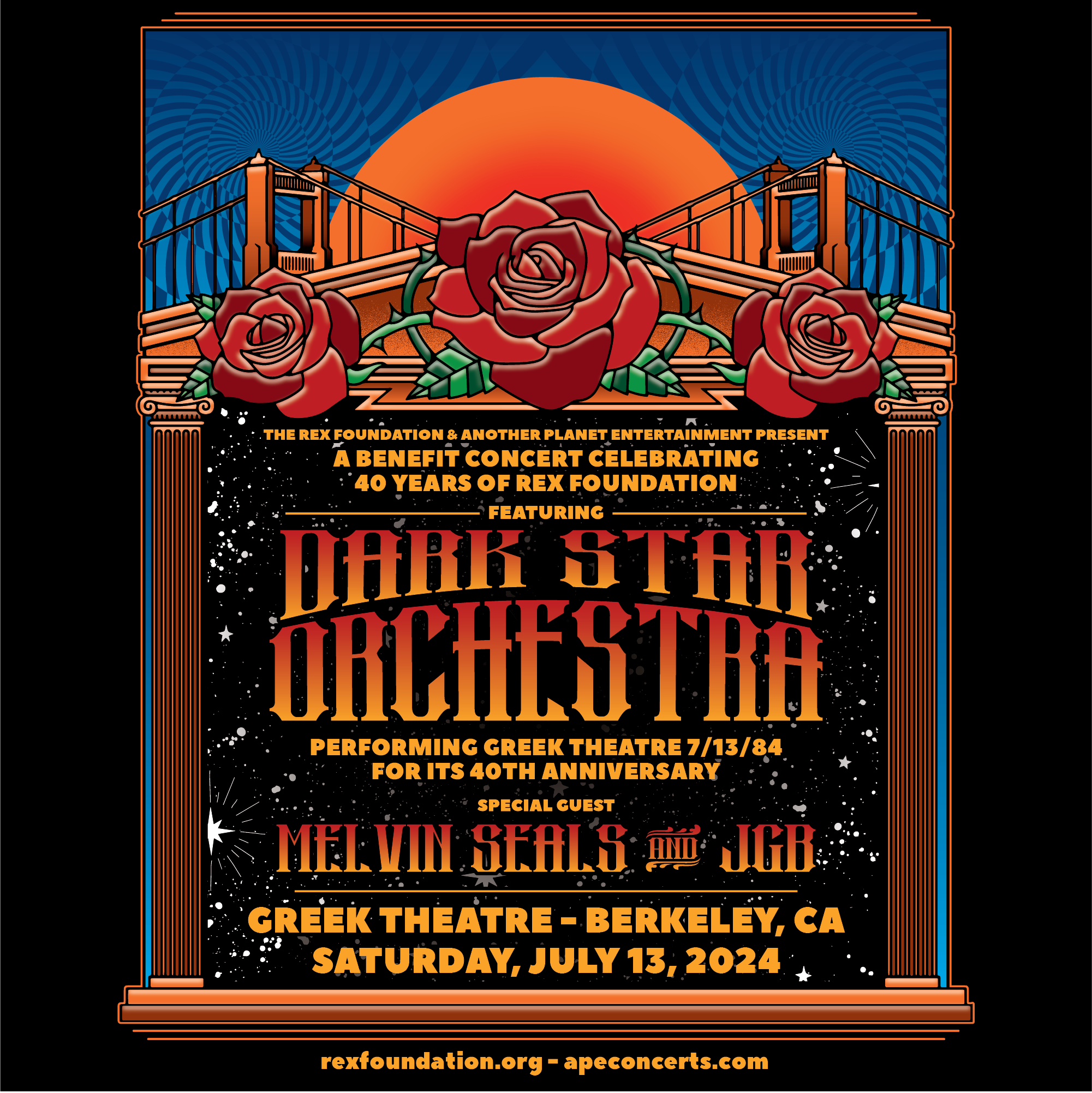

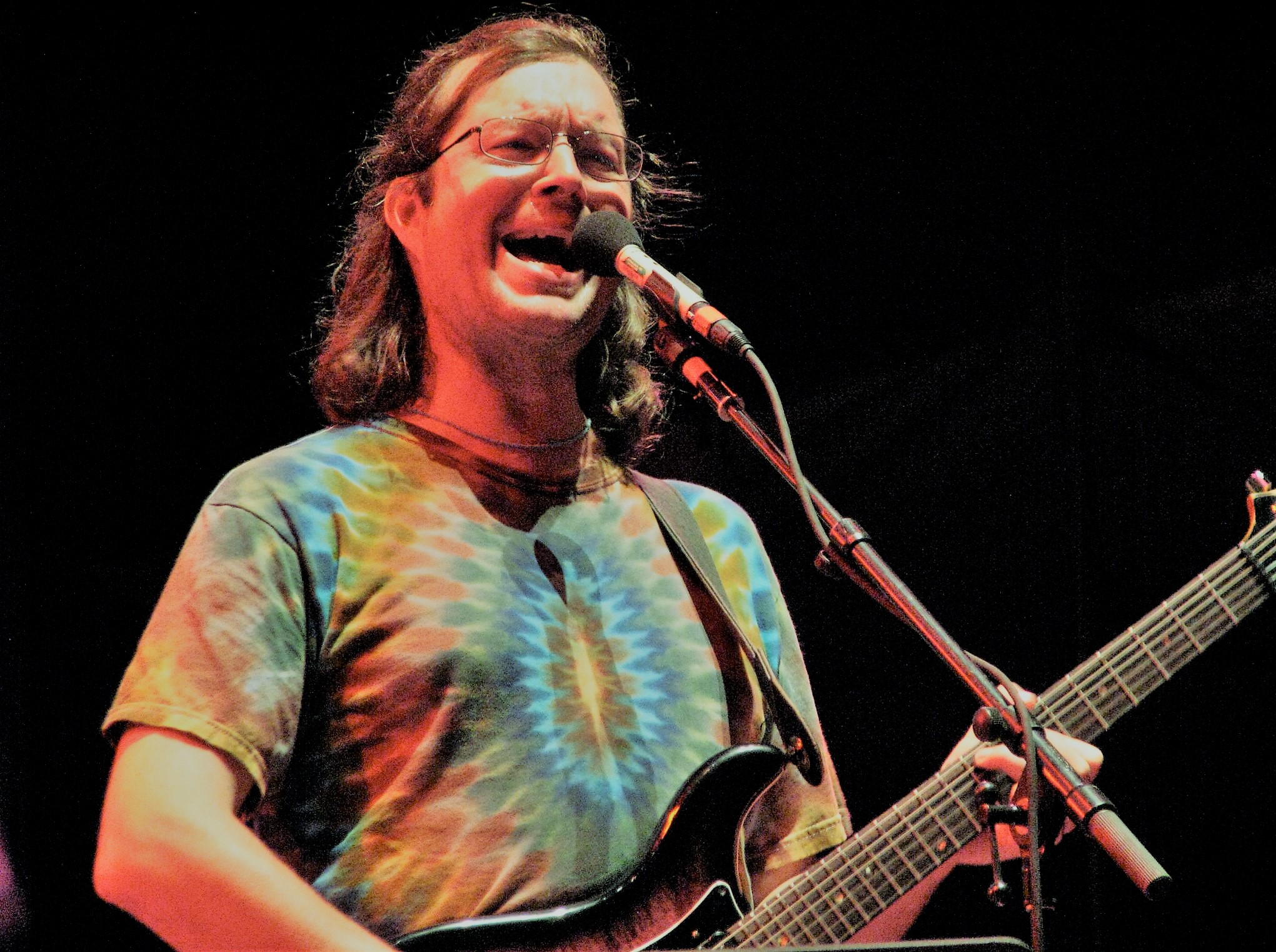

John Kadlecik co-founded Dark Star Orchestra, and went on to play in Furthur.

John K: I picked up the guitar around 1984. I’d been studying violin for about five years. I was kind of one of those weirdo kids who taught himself everything. I taught myself how to read music when I was seven. I took that into sight-singing music – I was in a family that was going to church every Sunday, which was boring as hell except it gave me a chance to learn sight-singing harmonies off the hymnals. … it was a nightmare things that my step mother dragged us into, one of those evangelical things with a four hour service every Sunday. …

When I was playing guitar, I dove into everything, and at that point, Led Zeppelin was the big draw. As a kid, I was into the Beatles, which was really, sadly really unpopular in the ‘80s. … The Grateful Dead were kind of around everywhere but I didn’t have anybody to turn me on to it until my first semester in college, at Harper College, a junior college in the Chicago suburbs. I was a music major and dropped out as soon as I started getting gigs.

It was a drummer friend who turned me on to the Dead, who’d also turned me on to pot and LSD, who said, “You gotta listen deeper than “Casey Jones” and “Truckin’.” He played Europe ’72 and Mars Hotel for me, and somewhere between “China Cat Sunflower” and “Unbroken Chain” I was hooked. I’d kind of been into this idea of new age music, but something that was a little dirtier—I liked the new age ideas, the new consciousness, really, but new age music isn’t really the same thing as new age philosophy. I was looking for some new kind of rock and roll, and then I saw the Dead, and realized that they’d been doing it.

I was looking for loose ends and unburned trails in music, and there they were …in my high school years I had been all through transcribing solos from dozens of guitarists, but I’d intuited that it was what was in the hands that makes the tone, as opposed to gear, ‘cause I couldn’t afford gear (laughter).

It was really seeing them live a year later in 1989 and realizing that ‘oh, this is what it’s about.’ The live show is what it’s about. The songs are just snapshots for a keepsake for the year. Everything was growing and had its own bleeding edge, every song had its own bleeding edge for the moment.

But my first show where I got to see them was the spring of 1989 at Rosemont Horizon. Went to the first and third shows and the middle show I was home going “What the hell am I doing here?”

So I was going, “how do I integrate this into what I’m doing?” I had a band called Uncle Buffalo’s Urban Mountain Review, which had a regular weekly house gig in downtown Chicago, a punk hippie acoustic trio, I played mandolin and violin in it, I didn’t even play guitar. Then there was Hairball Willy, and when it blew up, the opportunity to join a local long-running Grateful Dead tribute band, “Uncle John’s Band,” came my way, and I jumped on it.

It was like my first full-time music gig. But after a year, I was kind of disappointed. They had dialed themselves into the North Shore Chicago yuppie scene so much that there wasn’t much I could do. Hits, no long jams, no blues, no ballads…thirty songs a night in three one hour sets. Half the band had only seen the band once, and they weren’t even sure if they liked the band, but it was a good gig. A lot of guitarists playing Donald Fagen-type rock-jazz fusion stuff. Really tight, but didn’t understand what I called the “getting lost and found jam.” That’s what I called what the critics used to call noodling.

One of the things I had done in Hairball Willie for kicks one time once was to cover a whole Grateful Dead second set and had a contest, getting people to figure out what set it was. It sort of struck me then that it would be a fun framework for a Dead cover band, a way to keep the applause hounds and money grubbers from burying the core roots music, the blues and folk music, and the ballads and the psychedelic jam… a way to create our own postgraduate study program. And that was the birth of Dark Star Orchestra.

We’d get together on Tuesday nights every week, pick a set list, study what we could about it, and really the study approach wasn’t so much as find a show and try to transcribe it, as find three or four different versions of each song from the same year and figure out what hangs together about it. Really it was like, ‘what if they would take one of their shows and see what it would be like if they played the same set again the next day.’

To my mind Grateful Dead music is very intentional, they crafted a full-blown language like bluegrass or reggae, and yet somehow made it – managed to put it in a bigger box, while still incorporating elements of different idiomatic forms, like blues – “that’s definitely this thing, and here’s why.”

There’s always been a thing of taking a song from a writer and doing it in their own style. There’s also the other side of it, there’s people who – say do a Grateful Dead song in a bluegrass style, you know, is no different from doing a bluegrass song in a Grateful Dead style. There’s an arranging character that happens with the Grateful Dead. A lot of musicians play parts together – really that comes from big band – but the polyrhythmic thing, which is really what Dixieland was, is what I’m after. I’ve heard David Crosby refer to the Grateful Dead as electronic Dixieland.

Improvisation is a huge territory, and almost everyone that plays any of the traditional forms –reggae, bluegrass, country, klezmer – or whatever are improvising. That’s my frustration with the jam band label. Beyonce’s band, when they play live, jam the fuck out of those tunes. To me, “jamband” is the sanitization of psychedelic rock. It’s just supposed to be music for the mind.

I try to explain to people I meet casually what the Grateful Dead is about – people who have no idea who they are. And I say they’re kind of like the American Rolling Stones, if you need a pop culture metaphor to understand their significance. They were the emergence of rock music as an adult art form. They were there at the beginning, transforming it from teenybopper music to a real American art form. And they’re really woven into the tapestry of Americana. There are hobos that still hop freights, and they might not know G.D. very much, but they do know “Ripple” and “Friend of the Devil.” I followed the hippie movement underground into the Rainbow Family. And in that scene, they refer to something called the heart song. An individual expression thing, your personal ultimate expression song. And to me, in many ways, the repertoire of the Grateful Dead, the body of songs is in many ways collectively the heart song of the American experience.

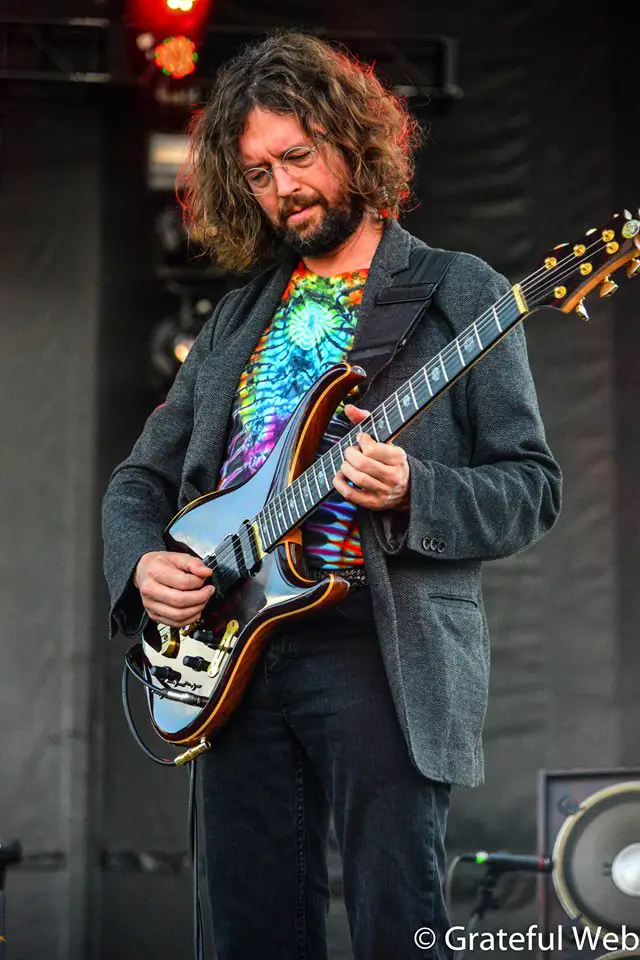

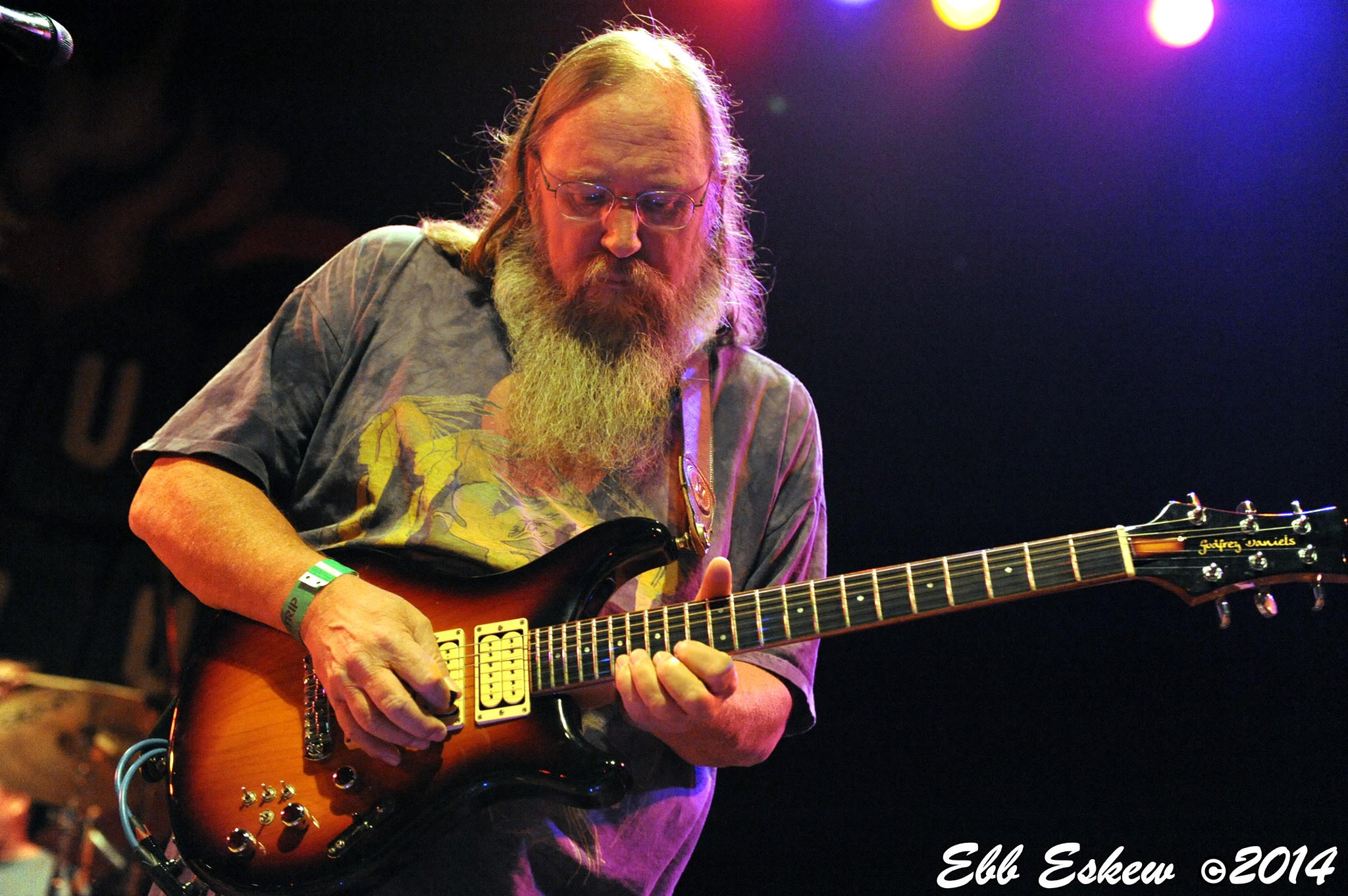

Dennis McNally: I first heard Stu Allen in 2005, at the “Comes a Time” Rex Benefit at the Greek Theatre that celebrated Jerry’s passing 10 years later. I hadn’t heard JGB in a while, and was running around doing my job when I suddenly heard someone singing a Jerry song in a voice that sent chills up my spine. I’ve been listening to Stu ever since. He played with JGB for seven years, and now fronts Mars Hotel.

Stu Allen: I was born in Savannah, and raised in Louisville, Kentucky. I was 15 when I picked up the guitar -- thanks to my parents for giving me my first one. I was inspired by the guitar-heavy music I listened to -- Hendrix, Clapton, Led Zeppelin. I got lessons once a week at House of Guitars in Louisville.

My first exposure to Grateful Dead was probably “Touch of Grey,” when I was in the 8th grade. Since it was the ‘80s, it was the MTV age, so the song was inextricable from the video – I remember the video being very funny, they were the Grateful Dead and there they were as skeletons playing, and that was interesting. And the song was good, but it didn’t fire off a spark just yet.

And then the Dead came to Freedom Hall in Louisville in 1989. The show was great, and what I remember talking about the next day was the keyboard player being – I didn’t know Brent’s name – “That keyboard player was on fire. He was really electrifying” – but the mind blowing part of it for me was the Dead Heads. Driving through the lot – “What is going on here?!?” – and then in the hall, I went out through the lobby to go to the bathroom and people are dancing all over the place, in the halls, and everything they were wearing – “Hang on, what is going on here?!?” So that moved the ball forward a little bit…

(I recalled a Louisville show that engraved itself on my own memory because the quite-enormous parking lot for both Freedom Hall and the Stadium was hosting the Dead Heads, a Jehovah’s Witness encampment, and a motorcycle show, everyone getting along famously.)

That was later, in 1993, because in ’89 at my first show there was camping in the lot, and then right after that it was – right after that – it was no more, and so as a young Dead Head I felt kinda cheated out of that whole experience. “We have to drive after the show now? Come on!” And I also remember coming to Freedom Hall in ’93 and seeing all these tents set up and I felt doubly cheated, because it was the biker rally. They were allowed to camp, and I was “Hey, come on!”

So after the first show, I didn’t see them for a couple of years, so it was about trading tapes, listening to them with friends and talking about the music, what makes one moment or another great. And having your perception and about music evolve.

As a player, I was jamming with guys in the first year. I was in a band or two in high school, nothing that we ever recorded, didn’t make any records or anything. Until college -- I went to St. Olaf College, in Northfield, Minnesota, south of Minneapolis -- I was in an acoustic group, Blue Man Jive, made a record, made a lot of great original music, and that lasted from ’91 to ’96. At the same time, I was hanging out with the guys from the Big Wu, who were also out of St. Olaf.

Moved up to Minneapolis, and one day the phone woke me up. Frist there was this guy, a member of Blue Man Jive, “This is what I think I heard on the radio,” that Jerry was dead. And I’m still waking up and trying to figure it out, get my bearings. Then my friend, who I was listening to tapes with and going to shows with in high school, he says, “Just wanted to make sure you’d heard.” That’s when I knew it for real.

And that seemed like the time to start playing Grateful Dead music – there weren’t any more shows. Someone else was putting a band together and saw a classified ad in a weekly, The City Pages, in Minneapolis, “Grateful Dead: Forming cover band. Need all instruments but bass.” We ended up calling it the Jones Gang, which we took from a show at Colgate College in 1977, where they had trouble with the monitors or something, and to fill in the time, the band started introducing themselves as the Jones Gang. “On guitar, Jerry Jones. On guitar, Bob Jones.” One of them was Julius P. Jones” but I don’t remember who or why. But the double meaning was that the band was now gone and we were all now jonesing for the music.

I lived there until the end of 1998, and then went to Boston to go to Berklee College of Music, and was there for four years, until 2002, then out for a year. And then a guy I’d played with a couple of times in Minnesota by the name of Jeff Cierniak who was in Melvin’s band, called me because Ron Penque was leaving the band. He was the bass player who sang the tunes. And Jeff was playing guitar, but didn’t sing. So they’d lost really two guys, and they thought, “How are we going to find a bass player who sings this stuff?” Melvin threw up his hands and was going to cancel the tour, as I understood it, and Jeff was “No no, we’ll come up with something. I’ll call this guy I know from Minnesota, and I’ll switch to bass.” So Jeff played bass on that tour. And I filled in, and was with him for seven years.

My first gig with Melvin was – he hired me sight unseen – so I met Melvin in the alley behind the bar at the first gig I did with him. And that gig went great. I hadn’t really concentrated on the JGB material, so I felt I was lucky that I had 12 shows to get up to speed. By the end of it, I was on board.

People ask me about the difference between Jerry’s playing with JGB and Grateful Dead, and it’s hard to answer. It’s different music, and so you play something that works with that music. There’s fewer players, and you might think there’s more freedom, but there’s also more space to fill. Since there’s more players in the G.D., there’s more listening and responding – there’s more to interact with. And Phil is playing off the beat, and Kahn is playing on the beat, so Garcia’s playing might emphasize the beat more with the G.D. and be more free to play off of it with Kahn.

Playing with Melvin was inspiring. He can really lift the vibe, the energy of a tune, and then continue to escalate when you think you’re all out, and just keep bringing it up. He can also bring it down to some beautiful places.

Instead of wanting to do a radical re-interpretation of G.D. music, I kind of take it to the opposite – I like to do other music in the style of the Grateful Dead. At our Tuesday nights at Terrapin, we’ll take other classic tunes and play them more like Grateful Dead style, find places to stretch out.

But the Grateful Dead ethos just seems to not only go on but get bigger. I mean, how powerful was Fare Thee Well? It was really something, being back in there after all those years, and you gotta think it was incredibly powerful for people who were never there and had been listening to the music for two decades and then they finally make it in to a show! It gives me goose bumps to think what that must have been like.

Being a Dead Head has gone viral.

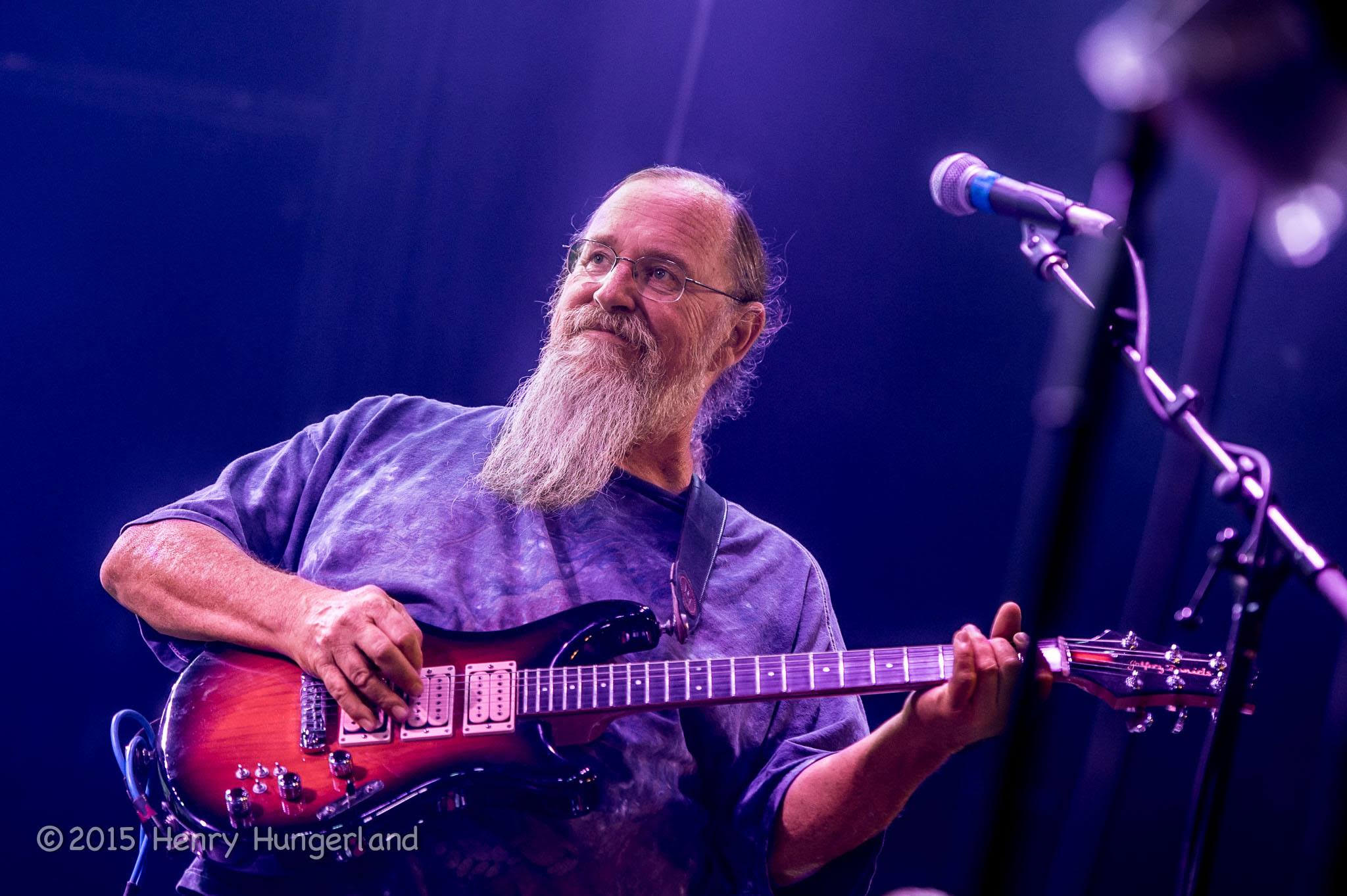

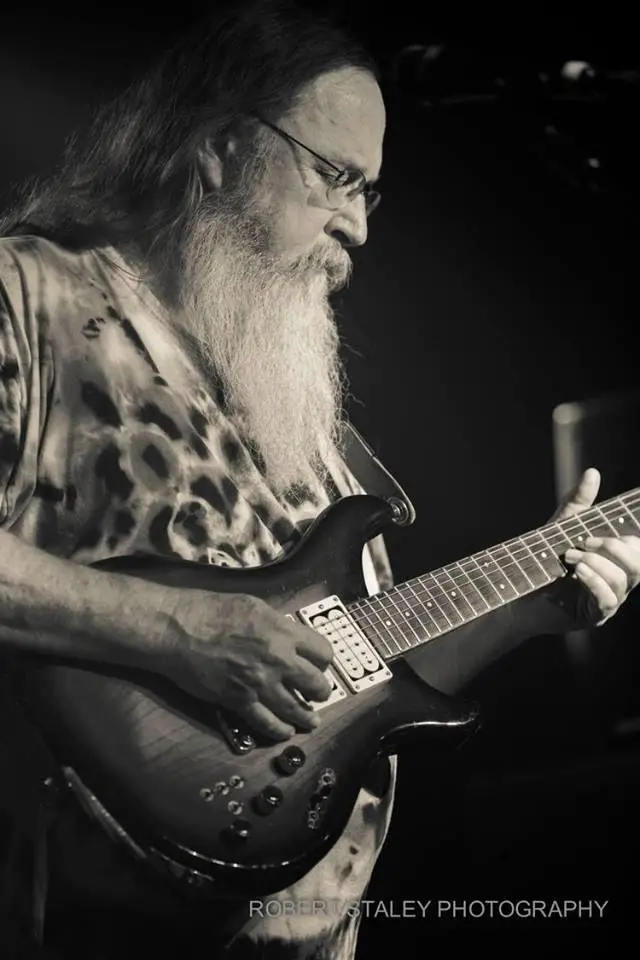

Dennis McNally: Craig Marshall is the lead guitarist for Cubensis, Los Angeles’s legendary Grateful Dead band—more than 4,000 shows, more than 25 years of playing.

Craig Marshall: I was born and grew up in Hawthorne, in South Bay, the Los Angeles area. I couldn’t go to the Beach Boys’ alma mater, I had to go to Leuzinger High School in Lawndale, which was closer to my house. The guitar thing started when my folks were approached by a door-to-door salesman. He was selling a piece-of-crap guitar and a 10-inch amplifier combo, and it included free lessons, for $400. And they bought it for me, because they knew I wanted to learn guitar. It was 1967, and I was a freshman in high school.

The lessons that came with the guitar happened a block away on Hawthorne Boulevard, and I went to exactly two of them. The instructor was an old hippie guy – he had long hair, some kind of hippie clothing, a tie-dye or something -- teaching the lessons, and he mentioned the Grateful Dead to me, saying “you gotta check these guys out. You gotta go see these guys.” When I went up for my third lesson, the old hippie was no longer there, so I said, ‘Well, I’ll see you later.” Never had a lesson since. But he’d advised me to get the first album, their only one at that point. Sure would like to thank that guy.

In those days, record players had a switch where you could drop things from the normal 33 rpm to 16 3/4 rpm…which effectively dropped the playback of the record one octave lower. So I would sit there and listen to Garcia’s licks at half speed, and I would copy those licks, and then work on trying to bring them up to speed. So I always have claimed that virtually, Jerry Garcia taught me how to play guitar, because that’s how I learned to play guitar – essentially self-taught by listening to Garcia on those albums at half speed.

There was no way I could play “Beat It On Down the Line” the way Garcia did it, unless it was at half speed, or “Cold Rain and Snow” or something like that. Eventually, I gained some facility – I was able to play, and that was my learning experience. I never got into music theory or anything like that, but I can play just about anything I want to by ear, and I’m happy with that. I would have loved to have been able to read sheet music, or know a bit more about theory, but so far, so good.

My first Dead show was November 11, 1967, at the Shrine Exposition Hall, here in L.A. One of the reasons I went was not only for the Dead but that I was a big fan of Blue Cheer, and they were on the bill, along with Buffalo Springfield, believe it or not. What a bill, when you think about it today. I can’t remember who headlined. The poster read, “Amazing Electric Wonders.”

I went with high school friends, meaning we were high and we had a great time. And that’s when I got on the bus. I especially remember the light show – the Exposition Hall was a rectangular building with a balcony that went all the way around, and in one corner they had a strobe light. And they had a three-way sound system – a stack on both outer sides and one in the middle. And two stages, so one band would be setting up while the other was playing. I remember not dancing much, maybe for reasons of inebriation.

I knew right away that the Dead resonated with me – I might have gone to the show a Blue Cheer fanatic, but I left a Deadhead. I said, “I’ve got to explore this” – so I just wore that album out. I went to the Newport Pop Festival the next year. I came up close when the Dead was playing, and during “Feedback” they were all facing their amps and bringing their guitars right up to them, causing that wonderful howl that they did – I was enough of a guitar player to know that this was pretty crazy, creating feedback instead of avoiding it, for musical experimentation. They also had this one beat that kept showing up in so many songs, great for dancing…and I remember thinking that I’d like to re-create this scene, but it would take me to 1987 to get to that place and form Cubensis.

I saw the Dead whenever they came to LA – once I saw them at The Bank in Torrance, which was really intimate, maybe 300 people. It was just a warehouse, I think they built electronics there during the day, and then at night it turned into this concert place. They had an amazing 360-degree light show that was projected from a platform hanging from the ceiling. Eventually the police closed the place down, but they had some great shows there. I saw Pink Floyd there as well. I remember going to Compton Terrace in Arizona and seeing them on some Indian land in those early days. But I was a single father and had kids and a job, so I couldn’t go to many shows in San Francisco. I remember a Chula Vista show that I loved. I saw as many shows as I could, though.

I graduated high school in 1970, went to El Camino College majoring in journalism, and then my girlfriend got pregnant and I had to get a job quick. Found one at the post office during Christmas rush, and they told me if I showed up every day, and worked hard they’d keep me, and I turned out to have a thirty- year career there as a letter carrier, delivering mail house to house on foot. The band was working, and sometimes I’d get to bed after playing a show at 2:30 and get up at 6:30am to work 10 or 12 hours. It was a little taxing some times.

Before Cubensis, I had two bands, a Top 40 band called Widow, and also an acid rock band called Green Mourning. We played around with not much success, but it was fun. Eventually a group of us were not happy with the frequency with which the Grateful Dead made it to L.A. I think the LAPD gave them a hard time too, which didn’t make them feel welcome. So for our own amusement, we started a band consisting of a friend of my brother’s, my sister’s boyfriend, a kid who lived in front of the rhythm player, a skateboard kid with a mohawk who played bass. We formed a six-piece Dead cover band, just for our own amusement, just getting high and playing music in somebody’s garage. Soon folks started asking us to play parties, and we had a club gig or two, then a festival gig, and all of a sudden we were playing all over the place. And we’re still doing the same thing today. It’s just grown to bigger proportions, with a far bigger audience.

I was the lead player, but I don’t sing Jerry’s parts – I sound like a frog. Other people were happy to take the singing parts. Richard “Chester” Lawson was the rhythm player. He was a Northrup employee. Brian Lerman was the skateboard kid/bassist. We had two drummers, one of which was Gene Aulicino, my high school buddy who I went through Boy Scouts with, and C. W. Causer, was the other drummer, who was my sister’s boyfriend. And we had a fellow named Tim Greutert on keyboards. And that was the first band.

We did OK. We called ourselves “Sugar Cubensis” (a takeoff on “Sugar Magnolia” and sugar cubes used for taking acid. At some point, some people who were looking for Björk’s band the Sugarcubes were showing up at our shows and getting really pissed that we weren’t them, so we cut it to just Cubensis. The name was C.W.’s idea – we were sitting around a fire on a camping trip and he came up with it.

For the Dead, losing keyboard players has been the curse, but for us, the drummer position has been the hot seat. We’ve lost three drummers to cancer. Gene first, and then C.W. last year, and also Steve Harris.

We got our first club gig up at Club Dead in the Valley, thanks to promoter Kenny Kulber, and then it just kept growing. Our biggest gig so far was around 7,000 people at the Hermosa Beach summer concert series last year. We once had about 3,000 people at a show at the Libby Bowl in Ojai with Vince Welnick appearing with us.

One of the things that attracted me to the Dead’s music was that there were no admission dues to be paid, you were automatically a member of the club just by your desire to be in the club. There weren’t any qualifications – you didn’t have to look a certain way or think a certain way. If you were kind, you were in. As musicians who play Grateful Dead music, there’s just no better thing than to incite happiness in people, get them dancing and enjoying themselves and getting away from life’s troubles for a while.

The Dead’s music is wonderful. It’s varied, it’s got something for everybody. As you well know, the Dead played country, rock, jazz, improvisational stuff… and it’s almost like they left a little space in the middle of the songs for bands like us to do our improvisations. Like in the middle of “Eyes of the World,” there’s a perfect place to jam—they used it, we use it, DSO uses it.

Let me tell you the story of the one time I met Garcia. In 1990 we were going to see the Dead in Eugene, Oregon, and our flight stopped over at San Francisco International, and there he was in the gift shop. My girlfriend went up and got an autograph and a hug…but I wasn’t going to bother him, because I figured everybody was always pestering him, but I knew I might not get another chance, so I went up and thanked him for all the good music. I said I was in a band called Cubensis and he nodded his acknowledgement of the name and what it meant. Then I revealed that we played all Grateful Dead music and he laughed in mock surprise and said, “Oh, yeah? So do we!”

I went on to ask him about his guitar effects and he launched a long dissertation about how he set up his effects, much of which was lost on me because I kinda got stage fright at that point because I was talking to “the man”, my favorite guitar player, but hopefully I absorbed some of it on some level. Anyway, I asked him how he felt about us playing his music and he said, “As long as you do a good job of it, go for it.” And nobody could dissuade me from doing it after that, because I received his permission in a way that completely satisfies me.