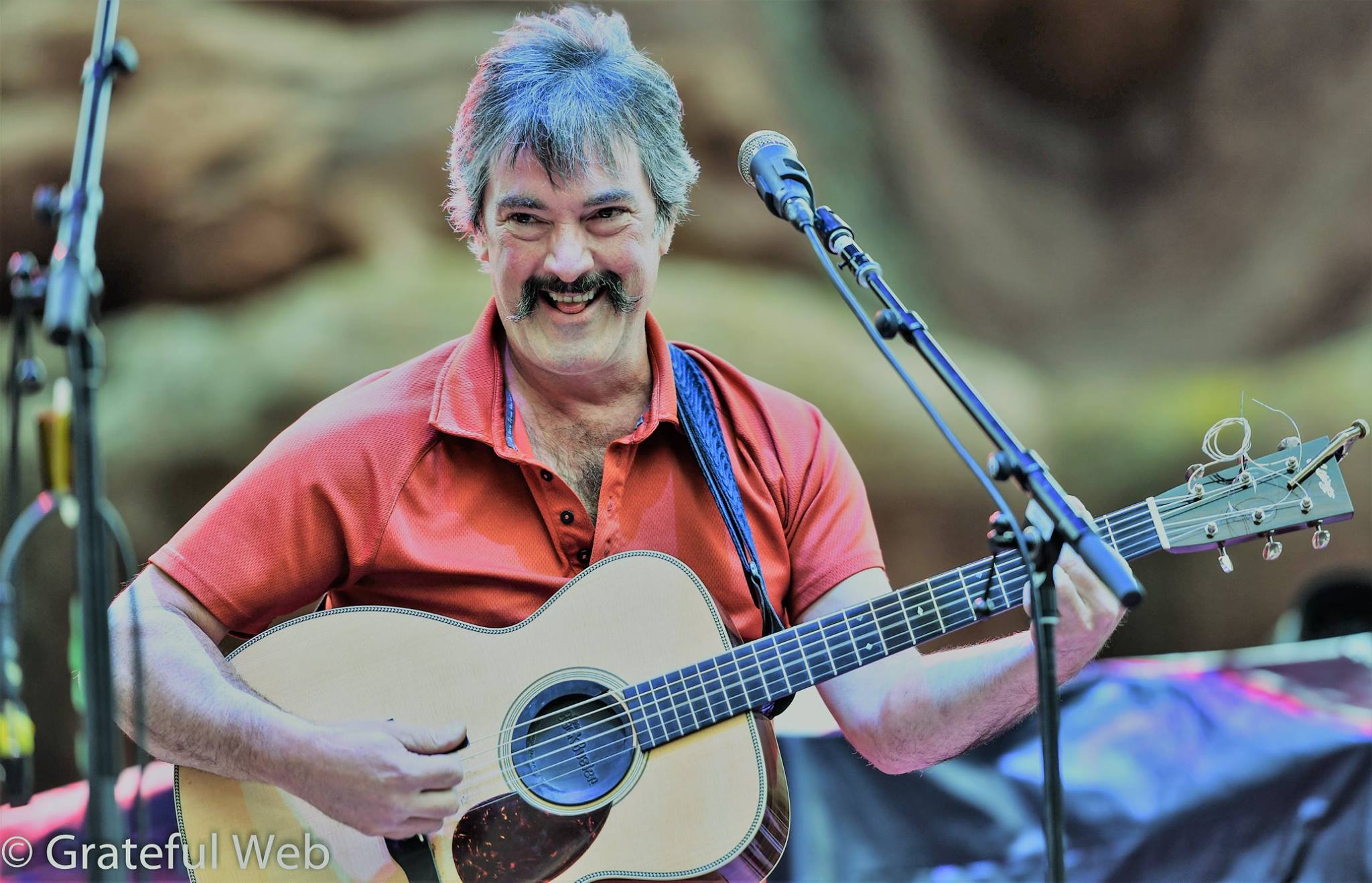

Jon Cleary's upbringing, amid a family of musicians in England, clearly put him on his lifepath. He was destined to be a musician. "There was never any question," he says. "That was all I really ever wanted to do."

His family, however, weren't just players, they were avid enthusiasts and collectors. "Everybody in the family was very, very passionate about music and had very strong opinions," Cleary adds. "When they weren't playing music, they were discussing it." They also hunted out vintage recordings. "My three uncles had that zeal for tracking down rare records and researching to find the incredible contributions of those that had been neglected. Nowadays, it is much, much easier." Even in England where even young Mick Jagger found recordings of Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, and Bo Diddley, finding some of the early Delta bluesmen were still hard to find. "Those blues records were certainly unavailable in England and unavailable in the States, too, I suspect, unless you were a really, really dedicated sleuth," Cleary says.

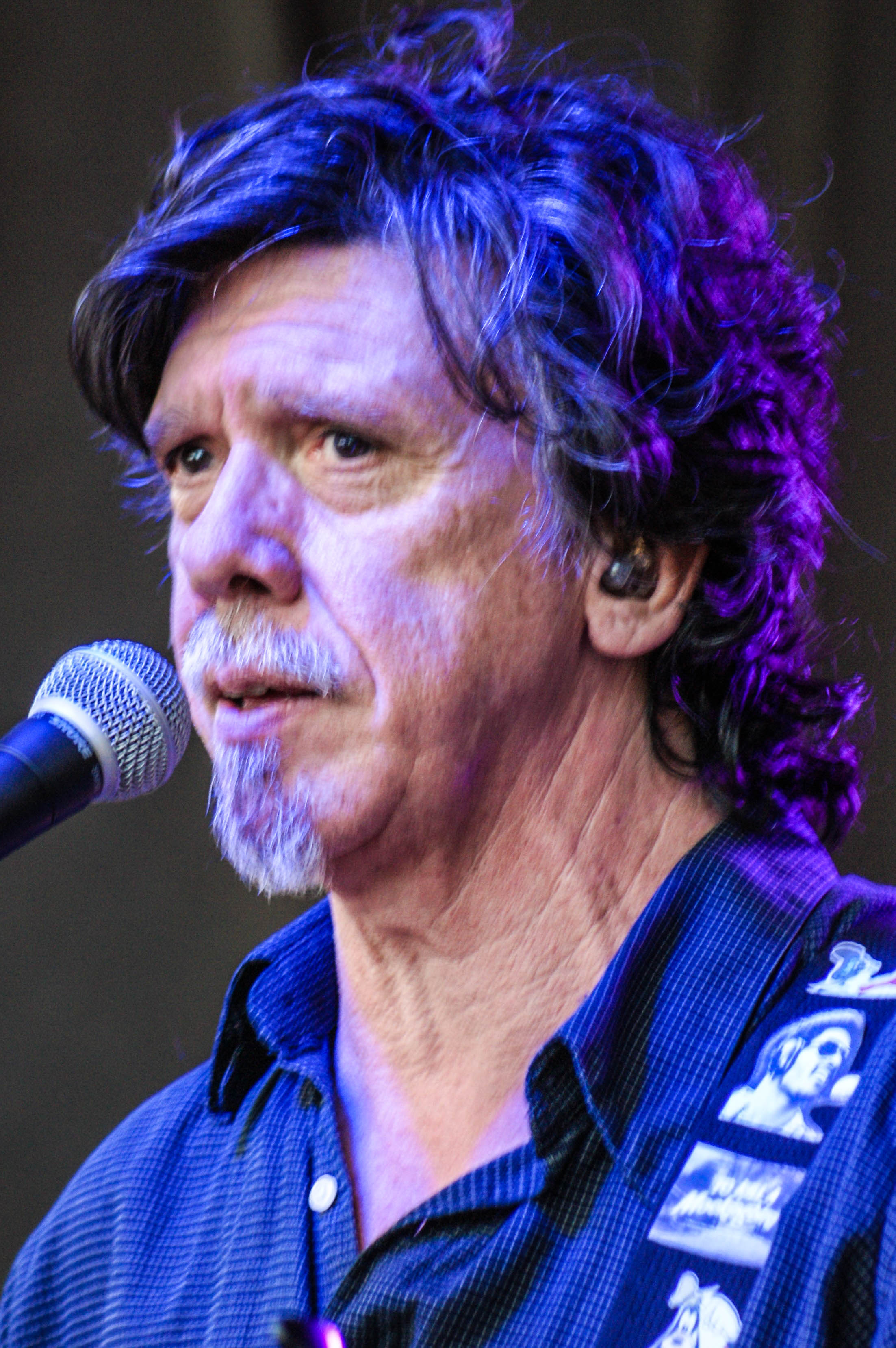

Yet, preservation of that kind of traditional roots music is necessary. "Some people are very dedicated to drawing attention to the styles of music of particular songs, of particular records, of particular artists. Otherwise, it would have been neglected," he says. "While I was growing up in England, to look to people like Dr. John and Bonny Raitt and Ry Cooder, people who made a point of educating themselves, doing it at a time when the old boys were still alive. These people were the source of information that was still there."

So, when Cleary came to America in the 1970s, he made a beeline for New Orleans, the home of the musicians he was learning so much about. He quickly found out, however, that America wasn't supportive of these roots musicians. Earlier, Mick Jagger had discovered that blues and R&B players were only being played on Black radio stations and weren't available to a wider audience, and certainly could not play with White musicians. In the 70s, even post the Civil Rights Act, Delta roots musicians were almost forgotten. "It was even more of a shame that a lot of that music wasn't even getting played on Black stations. It wasn't getting played anywhere. That shocked me and disappointed me the most," Cleary states. "I observed over the years that even in the Black community, with music, people move on, and things change. There was the desire to chase whatever was new, discarding the old." However, he does admit, that if the music scene had stayed the same, "You wouldn't have the evolution of that happened in Black popular music in the twentieth century."

Nevertheless, art forms like traditional roots music, including blues, can be revitalized without re-creating the work of blues artists note-for-note. It takes listening to these musicians–a lot–and then trying to capture their sound in your own way. Cleary's education in this music was furthered by what is now a New Orleans staple. "We're very lucky here in New Orleans because we have a great radio station, WWOZ." When he came to town, WWOZ, a jazz and heritage station, was just starting to broadcast. "You could hear Smiley Lewis and James Booker, and all those people. It wasn't until I started traveling around the States that I started to realize how unusual that was. We're very lucky here in New Orleans to have at least one radio station that still plays the kind of music that you don't get to hear anywhere else." In those early days when it was housed above Tipitina's, the radio station got creative and drilled a hole in the studio floor to lower down a microphone to broadcast live acts at the club.

Nevertheless, art forms like traditional roots music, including blues, can be revitalized without re-creating the work of blues artists note-for-note. It takes listening to these musicians–a lot–and then trying to capture their sound in your own way. Cleary's education in this music was furthered by what is now a New Orleans staple. "We're very lucky here in New Orleans because we have a great radio station, WWOZ." When he came to town, WWOZ, a jazz and heritage station, was just starting to broadcast. "You could hear Smiley Lewis and James Booker, and all those people. It wasn't until I started traveling around the States that I started to realize how unusual that was. We're very lucky here in New Orleans to have at least one radio station that still plays the kind of music that you don't get to hear anywhere else." In those early days when it was housed above Tipitina's, the radio station got creative and drilled a hole in the studio floor to lower down a microphone to broadcast live acts at the club.

"Traditional music in New Orleans took a bashing in the 70s and through the 80s when the music business changed," Cleary adds. "In New Orleans, there seems to be a battle against the big corporate radio stations, the big record labels, and those people responsible for distributing music."

However, there have always been people who have worked to revitalize roots music. "There were certain individuals who did a disproportionate large amount to breathe life into these beautiful forms of art, like Appalachian White American music. Here in New Orleans, there was a cat called Danny Barker who was very, very important. He was an old jazz musician in 70s who almost single-handedly breathed life into the brass band tradition, which before Katrina was really, really healthy in New Orleans. You go to places like Cuba and other parts of the Caribbean, which New Orleans is culturally tied to, and these forms of music are very much alive...New Orleans is one place where we do still actually have the remnants of a linear culture that developed over the last hundred years that is not completely smothered out by top 40 radio's play lists. Since Katrina, of course, that very delicate situation is harder to maintain. Fortunately, there are still brass bands playing in New Orleans, but a lot of musicians have not come back. Half of the population have yet to come back, including some of the musicians."

As a young performer in the 70s and 80s, Cleary soaked up every note he could in New Orleans. Here, he switched from guitar as his main instrument to piano because of the infectious stride piano that so underlined New Orleans music had gotten into him. He used to go to clubs at night and listen to everybody and then come back to his rooming house where there was an old upright piano and try to emulate what he had heard. Live music gave him a depth of understanding of the legacy of traditional players such as Professor Longhair and Jelly Roll Morton and today's Dr. John.

Cleary recognizes that this New Orleans sound often is the result of one person with an idea who influenced a generation. "In the fifties, it was cat called Dave Bartholomew." Bartholomew was responsible for moving New Orleans music from big band and jump blues to R&B and Rock and Roll. "Before him, it was a guy called Paul Gates. In the 60s and 70s, it was a guy called Allen Toussaint." Toussaint not only played piano with Etta James, Albert King, and Joe Cocker, he produced albums for Dr. John and arranged the horn sections for The Band and Paul Simon. His songs have been covered by Robert Palmer and Bonnie Raitt.

"The best music is stuff that's lyrically substantial and is musically substantial," Cleary insists, but adds, " If Professor Longhair had been a musical purist and insisted on playing strict arrangements of Jellyroll Morton tunes, he never would have come up with 'Big Chief,' 'Tipitina,' and all the great signature tunes. There's got to be a forward motion. You observe and respect tradition. You take from it, and you build on it. You do that by writing new material and coming up with new ideas."

"The best music is stuff that's lyrically substantial and is musically substantial," Cleary insists, but adds, " If Professor Longhair had been a musical purist and insisted on playing strict arrangements of Jellyroll Morton tunes, he never would have come up with 'Big Chief,' 'Tipitina,' and all the great signature tunes. There's got to be a forward motion. You observe and respect tradition. You take from it, and you build on it. You do that by writing new material and coming up with new ideas."

Though New Orleans has a wealth of talented musicians, Cleary notes that the city doesn't have a lot of songwriters. "That's not to say there aren't some really gifted songwriters, band leaders, and arrangers here," he says. "That to me was always such a challenge to try and write new songs."

New Orleans, yet, creates an atmosphere for music to happen. "By virtue of living in New Orleans, performing and rehearsing with New Orleans musicians, we come out with a sound that couldn't come from anywhere but New Orleans," Cleary says. "You don't necessarily have to resort to the clichés about Bourbon Street and crawfish and gumbo and Mardi Gras....I like to hear cats, taking the old stuff, bringing it on board, absorbing it all, putting it through their filters, and coming out with something that is one increment further down the line."

This is something Cleary aspires to do himself. "The artistic challenge really is to generate all of your energies into taking from the traditional and making something new, rather than rehash it. I think it's good to pay tribute to those stars who have gone before, but what I try and do is both really. When we play a show, we play some old traditional New Orleans music to our own tilt that ends up sounding a little bit different than others do. But the challenge is to play some new songs and new arrangements, to stretch all the musicians."