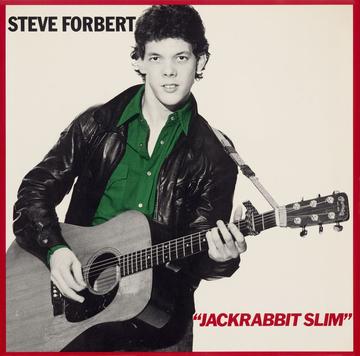

Among the Ramones’ blitzkrieg boppin’, the Talking Heads’ art-school New Wave and Blondie’s thrift-store garage pop at the now-legendary CBGB’s in the late ’70s, Steve Forbert stood tall as the lone troubadour. But it didn’t matter to him. “I never thought about it being strange to play there,” he recently confided from Nashville, his current home base. “I just figured they had live entertainment. I had done other auditions I didn’t get hired for, so what I did have to lose?”Forbert left Meridian, Mississippi — down state from Elvis Presley’s Tupelo homeland — for New York City in June of 1976 to play music. “A lot was happening in New York at the time,” he recalls. “Even in Mississippi, we were able to acquire Patti Smith’s Horses and the Ramones were out — that was all very exciting.” He busked in the subway and Grand Central Station. “I was going anywhere there was a rumor of an open mic,” with Folk City’s hoot nights being the open mic crown jewel. “It was like being a kid in a candy store,” he remembers. “I made a lot of friends. I could learn a lot from people who were good, and I could learn a lot from people who were bad.”He certainly learned how to craft a good song, as his career-launching first two albums — the aptly titled debut Alive on Arrival and its follow-up Jackrabbit Slim — well demonstrate. On March 26, Blue Corn Music is releasing those albums as a two-disc set (complete with a dozen rare bonus tracks), providing a fresh opportunity to appreciate the Southern grace and youthful energy, the honeysuckle innocence and gravel-road grit that Forbert effortlessly imbued into songs like “Goin” Down to Laurel,” “What Kinda Guy,” “Say Goodbye to Little Jo,” “Complications” and his breakthrough hit “Romeo’s Tune.”Rolling Stone contributing editor David Wild, in his liner notes, figures that Forbert made “one of music’s greatest entrances ever, arriving fully formed as an extraordinary singer-songwriter — a subtle troubadour for his times, and for all time too. Now or then, you would be hard-pressed to find a debut effort that was simultaneously as fresh and accomplished as Alive on Arrival . . . it was like a great first novel by a young author who somehow managed to split the difference between Mark Twain and J.D. Salinger.”Critics were heaping praise on an unsigned Forbert when he was playing clubs like CBGB’s and Kenny’s Castaways. In 1977, the New York Times’ John Rockwell created a buzz when he wrote, “What makes him remarkable is that he’s good already, when he’s still growing. And at his frequent best, he’s already a star.”As many labels quickly became interested, Forbert worried about being manipulated into someone that he wasn’t — turned into to a Johnny Cougar, in his words. He wound up signing with Nemperor Records because he trusted its founder, Nat Weiss. “I just felt if Nat said something it would be true and he would let me pick my producer.” Forbert remains friends with Weiss to this day.Forbert selected studio veteran Steve Burgh to produce after being impressed by an album Burgh handed him one night in a club. Not wanting to sound overproduced, the artist refused to have overdubs or reverb on Alive. However, after Bonnie Raitt said that she liked the album but it needed some reverb, the admittedly stubborn Forbert acquiesced. “I owe some thanks to Bonnie Raitt,” he confessed. “Bonnie set me straight on that.”He owes Barbra Streisand a debt of thanks too. He had chosen Joe Wissert to produce his second album but Wissert got hired to work on a Streisand album just before Forbert’s Nashville sessions were to begin. Fortunately, late-minute replacement John Simon (The Band, Simon & Garfunkel) proved to be “fantastic,” according to Forbert. He credits Simon pushing for a third recording session in order to get “Romeo’s Tune” right. While the song stands as his greatest hit and best known number (Keith Urban covered it a few years back), Jackrabbit Slim offers more than just “Romeo’s Tune.” In his liner notes, Wild notes that the album, with its many memorable tunes, beat “the sophomore jinx and then some,” showing “great artistic growth” and featuring “songs that are among Forbert’s most enduring.”Since the double-barrel blast of Alive on Arrival and Jackrabbit Slim, Forbert has continued creating more albums “full of focused, intelligent and sharp songs” (as critic Steve Pick recently wrote in Blurt), including his Grammy-nominated Jimmie Rodgers tribute Any Old Time. Last year’s Over With You accumulated more accolades, with All Music Guide’s Steve Leggett calling Forbert “a wonderful songwriter with a clear and sharply observed vision,” and American Songwriter’s Hal Horowitz describing the CD as “all lovely, melancholy, lyrically moving and beautifully performed.” The songs on Alive on Arrival and Jackrabbit Slim, with their special blend of folk, rock and soul, form the foundation of Forbert’s music and remain a vital part of his live performances. “I do still enjoy playing these songs,” he says. “There’s nothing wrong with starting out a show with “Thinkin” and nothing weird about singing ‘Everybody here seems to like to laugh’ [the opening lines of “Going Down To Laurel”].” He finds it gratifying that these songs have stood the test of time and have touched so many people. “A lot of people who discovered Alive on Arrival took it real personally and that has really been a great thing.” Among those Alive acolytes is David Wild, who states in the liner notes that “one of the many things that make this life so much more beautiful than strange is truly great music and that is assuredly what Steve Forbert has given us right from his arrival until today.”The artist sums up his first two albums this way: “I try to make music that has lasting power all the time but those two were the right people at the right time and right place . . . Had it been two years later it might not have happened (or) two years earlier, it might have been different. Those two records — I am proud of them.”