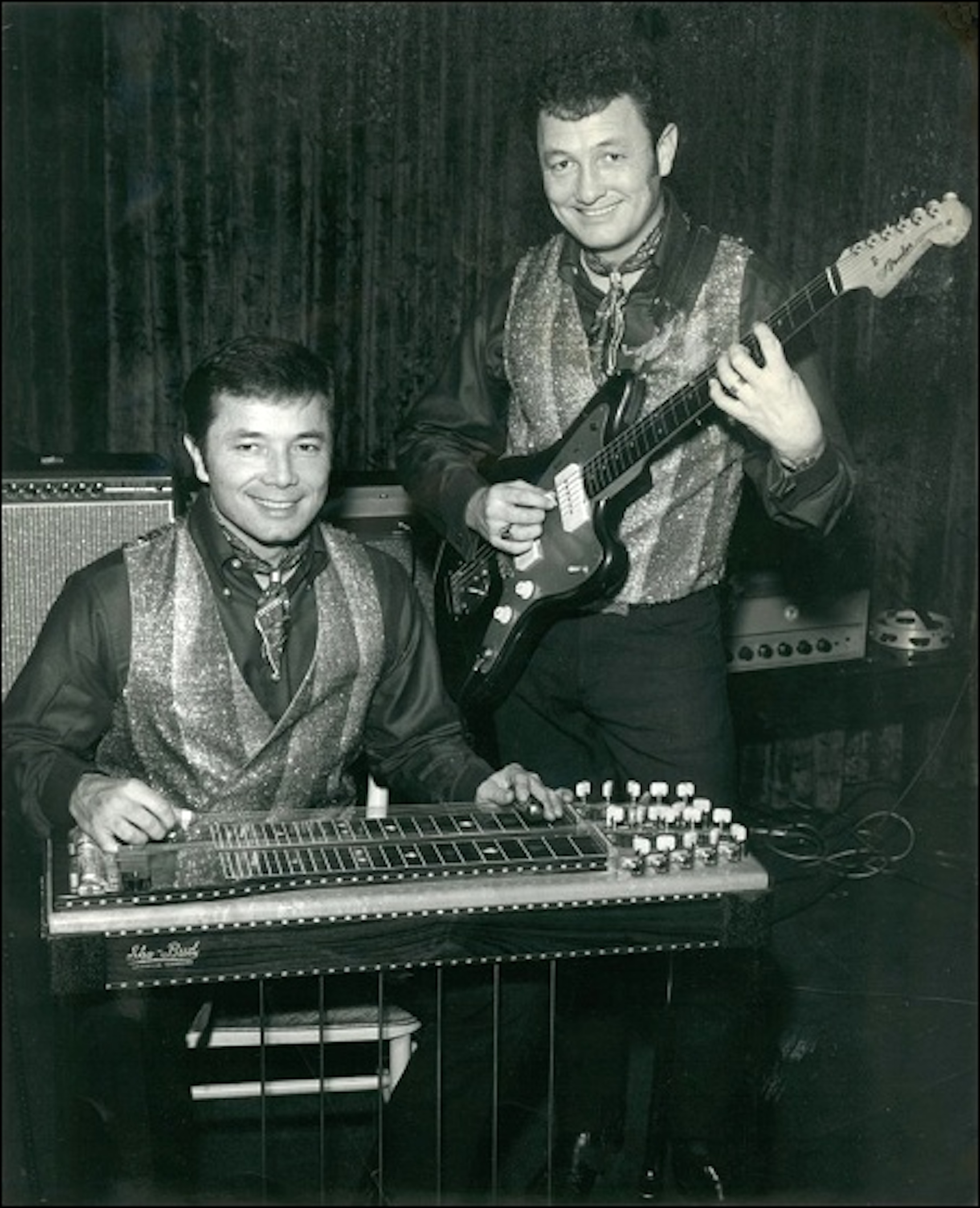

Best-known for gracing the pedal steel chair in Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen, Asleep at the Wheel, and the New Riders of the Purple Sage, Bobby Black is one of the greats at his chosen instrument and one of the last members of the first generation of players to introduce it to American music. And he is definitely the only member of that club who spent most of his life in Northern California, San Mateo to be specific.

Compiled by Myles Boisen, a music veteran and studio professional who played a lot of shows with Bobby, Seventy Years of Swinging Steel from Little Village (#1044) is a wonderful compendium that displays Bobby's artistry in the best possible way. It starts with an appearance at a San Jose department store in 1954, and includes a brilliant version of "Water Baby Blues," with Bobby and brother Larry trading riffs on what Bobby called "just a boogie woogie thing." Then the music cruises through a Gershwin tune recorded in his guitar playing brother Larry's bedroom to some Duke Ellington from 1991-2. They only got four down before Larry passed, surely one of the great lost albums. The fact that Bobby was a serious student of American jazz,

with influences like Charlie Parker (and also Andres Segovia), along with his impeccable taste and musical humility, is one of many reasons that he was so special.

His wide range didn't always help. He tells the story: "We were playing on an early TV show, the Hoffman Hayride, and it was an audience that just wanted to hear country music— actually, they called it hillbilly music then. We got away with playing some Western swing, as long as it wasn't too fancy, but we started doing those jazz types of things, like "A Foggy Day in London Town," and we were told by the people running the show that they didn't want anything like that. So we did `Foggy Day' and we got fired."

The instrument originated in Hawaiian music with steel guitar played horizontally, known as "lap steel." In the `30s manufacturers added a resonator and then an electric guitar pickup to make it more audible, and then in 1940 added pedals so that the picker could play a major scale without moving the bar (held in the left hand to affect tuning; picks on the right hand) and also bend notes into harmonies. It's a challenging instrument, the only one that requires both hands, both feet, and both knees. As the 1940s passed, it became an essential part of country music.

Bobby was born in Arizona, but by the age of eight he lived in Burbank, where he heard Harry Owens and the Royal Hawaiians, one of whom was steel player Eddie Bush. One side-effect of WWII was mass migration, including Southern and Oklahoman/Texan country music fans. The father of "Western Swing," Bob Wills, settled there. So did Spade Cooley, whose pedal steel player, Earl "Joaquin" Murphey, was a particular favorite of Bobby's.

When he was thirteen, the family moved to san Mateo. Already a piano player, the following year he got his first guitar, a lap steel. His first lessons were frustrating, and then he got lucky. He heard a song by Jerry Byrd, "Steelin' the Blues." Bobby wrote him a fan letter, and got a quick reply teaching him Byrd's C6 tuning. Armed with that information, he taught himself to play by ear.

His slightly younger brother Larry picked up the guitar and as a team they landed their first pro gig with the Double H Boys, a band with a weekly radio show. Later at the ripe age of 17, he and his brother then joined Shorty Joe and the Red Rock Canyon Cowboys, who had a regular gig at Tracy Gardens in San Jose. He'd never forget the place, since in 1952 he got to meet Hank Williams there.

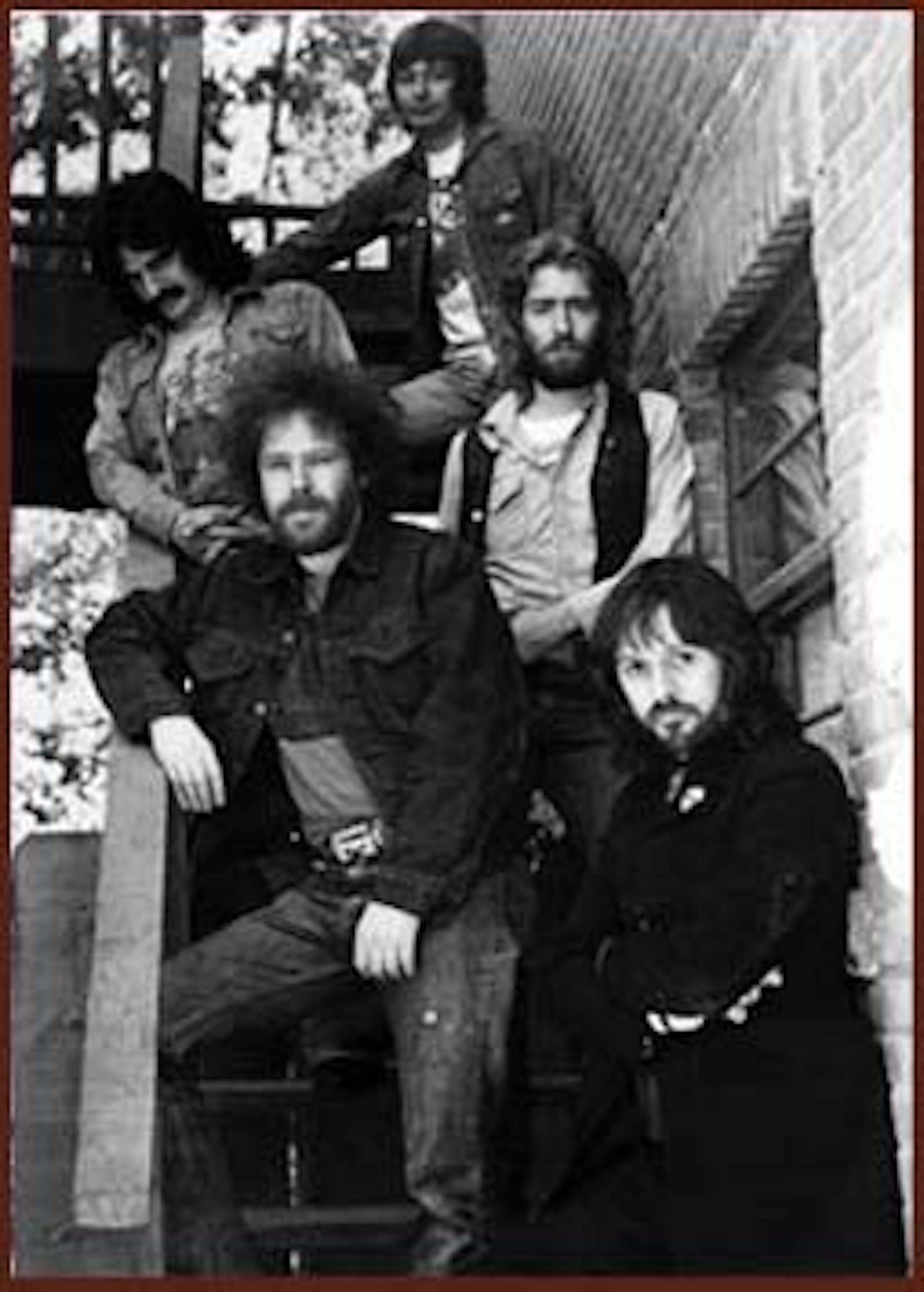

Bobby joined Blackie Crawford and his Western Cherokees, moved to Beaumont Texas, and ended up taking part in some of the first recordings for Starday, an early and important country label. Lots of bands followed as he and his brother scratched for a living, at one point in the sixties even donning green Beatles wigs to play rock and roll. Finally, in 1970 he met Bill Kirchen, the lead guitarist for Commander Cody, at a San Jose venue called Cowtown. The Airmen were a decade younger and a whole lot rowdier, but they loved the country-rock music they played, and he joined up.

Cody guitarist John Tichy reflected: "I always thought we were a bunch of inspired amateurs. All of a sudden, Bobby joins, and the whole thing came together. I realized, `Oh, we're actually pretty damn good!' He tied together all these loose ends, and turned it into a great band." You can hear that on the studio albums Cold Steel, Hot Licks, and Truckers' Favorites (listen to "Truck Driving Man"!), Country Casanova, Tales From the Ozone, and We've Got a Live One Here, and on Live From Deep in the Heart of Texas, recorded at Austin's legendary Armadillo World Headquarters.

Bill Kirchen experienced playing with Bobby with some awe. "Bobby, for me, was the living link to the past. But he also was the most advanced player in the band. We could look all the way back and all the way forward with him. He was the guy who met Hank Williams, started playing in the '40s on a straight (lap) steel... And on the other hand, he was the best bebop player in the band. It was just extraordinary."

Myles Boisen, who curated this collection, wrote: " It has been my great pleasure - and a life-changing experience - to have shared the bandstand, the studio, numerous storytelling sessions, and a great friendship with Mr. Bobby Black. The day Bobby showed up at my recording studio with a large box of unreleased tapes, cassettes, and CDs I knew I had discovered a goldmine that I just had to share with the world. These tracks show Bobby to be not only an important trailblazer on the pedal steel (while still a teenager!) but also a virtuoso with a solid command of western swing, country, jazz, and Hawaiian steel styles. And now, in 2021—

seventy years after joining Shorty Joe Quartuccio's Red Rock Canyon Cowboys—Bobby is still swingin'.

Jerry Garcia told Bobby that the awards he's gotten from Guitar Player as best pedal steel player had embarrassed him. "And people like you are way down the line, and that's not right."

Garcia was right; Bobby deserved lots more attention, and this collection from Myles is truly called for. Bobby, typically, is humble about it. "All of a sudden, they showed me this presentation, and it really blew my mind . . . I didn't realize it was that serious. I'm just pleasantly surprised by the whole thing. I had never planned that any of this stuff would be heard by other ears. Myles did some miracles in the studio, cleaning up stuff that needed it, made it listenable . . . I'm sure happy about it. It's all a really nice surprise to me."

Little Village Foundation is a nonprofit record company whose mission is to present music that might otherwise fly under the radar. Learn more at www.littlevillagefoundation.com.