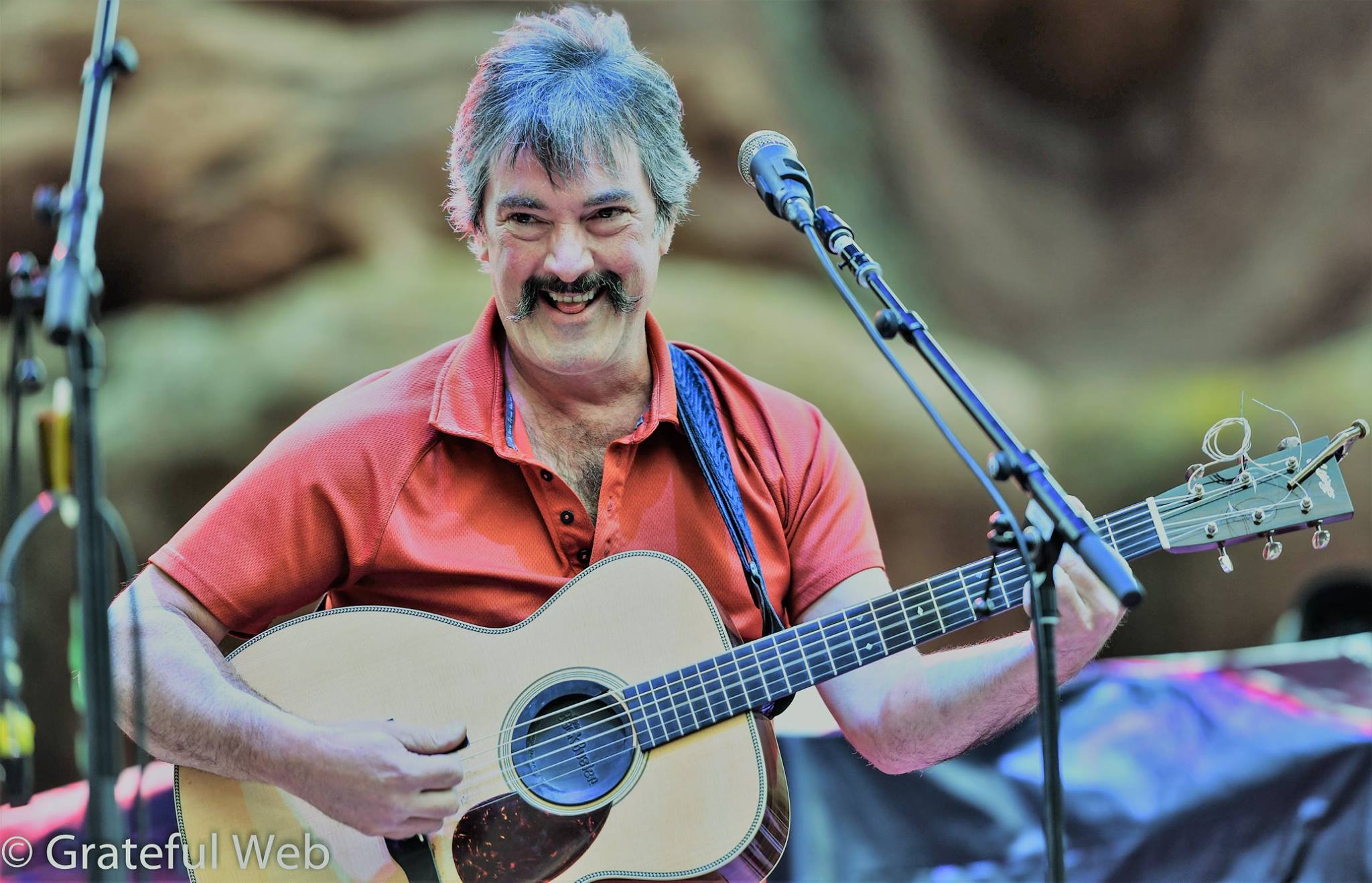

For classical composer Lee Johnson, tackling the work of the Grateful Dead was like discovering the musical foundations of a new foreign country. Johnson is known for his concert pieces, choral works, short operas and musicals, planetarium soundtracks, and solo/ensemble pieces that cross into jazz and big band music. Some of these disparate elements also find their way into his full-length symphonies where he has even added world music, a jazz/rock band, and whale song to his orchestras.

But it is his treatment of Grateful Dead songs that has stretched Johnson's creativity even further. In Dead Symphony No. 6, he has used ten Grateful Dead songs as inspiration for a full-length orchestral piece, recorded with the Russian National Orchestra. This symphony will make its world debut live in August with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra in celebration of Jerry Garcia's 66th birthday.

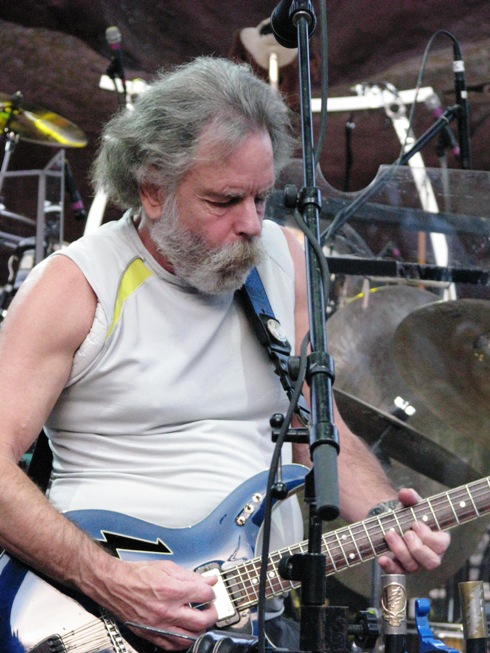

This work is by no means a simple transcription of Grateful Dead songs to the symphonic setting. It is an original work, which Johnson approached with dedication. Though some people may not approve of Johnson's tinkering with Dead tunes, wanting a note for note recreation of the Dead experience, it really would be totally antithetical to what the Dead did and what the Dead founders still do in their respective bands. The symphony structure could not ever become a Dead tribute band—and shouldn't. Too many pop singers, classical vocalists, and orchestras have taken rock music, especially that of the Beatles and others, and brutally tampered with the soul of the music, trying to bend it into their own styles while keeping the song's structure intact. Anyone who has ever heard an operatic voice sing, "Here Comes the Sun," knows exactly what almost sacrilege that is.

Johnson, however, did what only a composer of his quirky genius could do. He immersed himself into the music of the Dead and created something that even Jerry Garcia himself would have approved.

When deadhead Mike Adams approached Johnson with the idea of a Dead symphony, Johnson knew that he would have to be educated in this music. Adams never flinched as he instructed a classical music professor and began to provide him with discs and history. "I took on all of their repertoire, the song lists, the history, the publications of what the Grateful Dead did for decades. I had to become the student of all that," says Johnson. "The process of classical composition is pretty close to that. The studying of dead composers is my daily bread... I guess that should make me rather well suited to this task. But those who have tried this kind of thing before, the result is deplorable. We all know when it doesn't work."

Johnson also examined American culture to see what made this music so appealing. And, of course, he needed to understand the jam audience and how that today it is composed of a lot of players, many of whom are as technically-trained as classical musicians in both jazz and classical music. So, Johnson's target audience would be a mix of classical music enthusiasts, technically-trained jam musicians, and good ole Deadheads.

Johnson also examined American culture to see what made this music so appealing. And, of course, he needed to understand the jam audience and how that today it is composed of a lot of players, many of whom are as technically-trained as classical musicians in both jazz and classical music. So, Johnson's target audience would be a mix of classical music enthusiasts, technically-trained jam musicians, and good ole Deadheads.

In order to write a symphony, Johnson needed to wade through the enormous Dead catalog and narrow his composition to a few inspirational pieces that would provide him with musical ideas. "Of course, everyone has their favorites," Johnson says. "The list that I formed as I culled from a massive list I thought could fit got harder and harder to set something aside....You kind of have to comfort yourself that you're not going to miss the opportunity to work with the piece you really fell in love with. But a symphony has to have some kind of internal integrity."

As Johnson then began to write each part of the symphony, he was using his short list of ten Dead songs as pure inspiration. There are some melody lines there, but they have been set up with appropriate, often lyrical, introductions, letting the melody float out of it organically. "Organic is a critical word for classical composition, too," Johnson says. "It's easy to use convention or devise to make sound happen. You can train students to do that very quickly. But to make it organic and to make it fit is, of course, another demand."

In addition, those melody lines became the encores that are embedded in the symphony. "The most transcription-like movements are also embedded but those would be extracted in a live performance to become the encores," Johnson explains. These melody lines become what Johnson calls "palate cleansers or some breathing space" for listeners who might be struggling to keep up with the complexity of the symphony. "'Sugar Magnolia' and then, not so much so, 'Mountains of the Moon' are almost in the spirit of a transcription even though I did it through the eyes of Elgar."

In addition, those melody lines became the encores that are embedded in the symphony. "The most transcription-like movements are also embedded but those would be extracted in a live performance to become the encores," Johnson explains. These melody lines become what Johnson calls "palate cleansers or some breathing space" for listeners who might be struggling to keep up with the complexity of the symphony. "'Sugar Magnolia' and then, not so much so, 'Mountains of the Moon' are almost in the spirit of a transcription even though I did it through the eyes of Elgar."

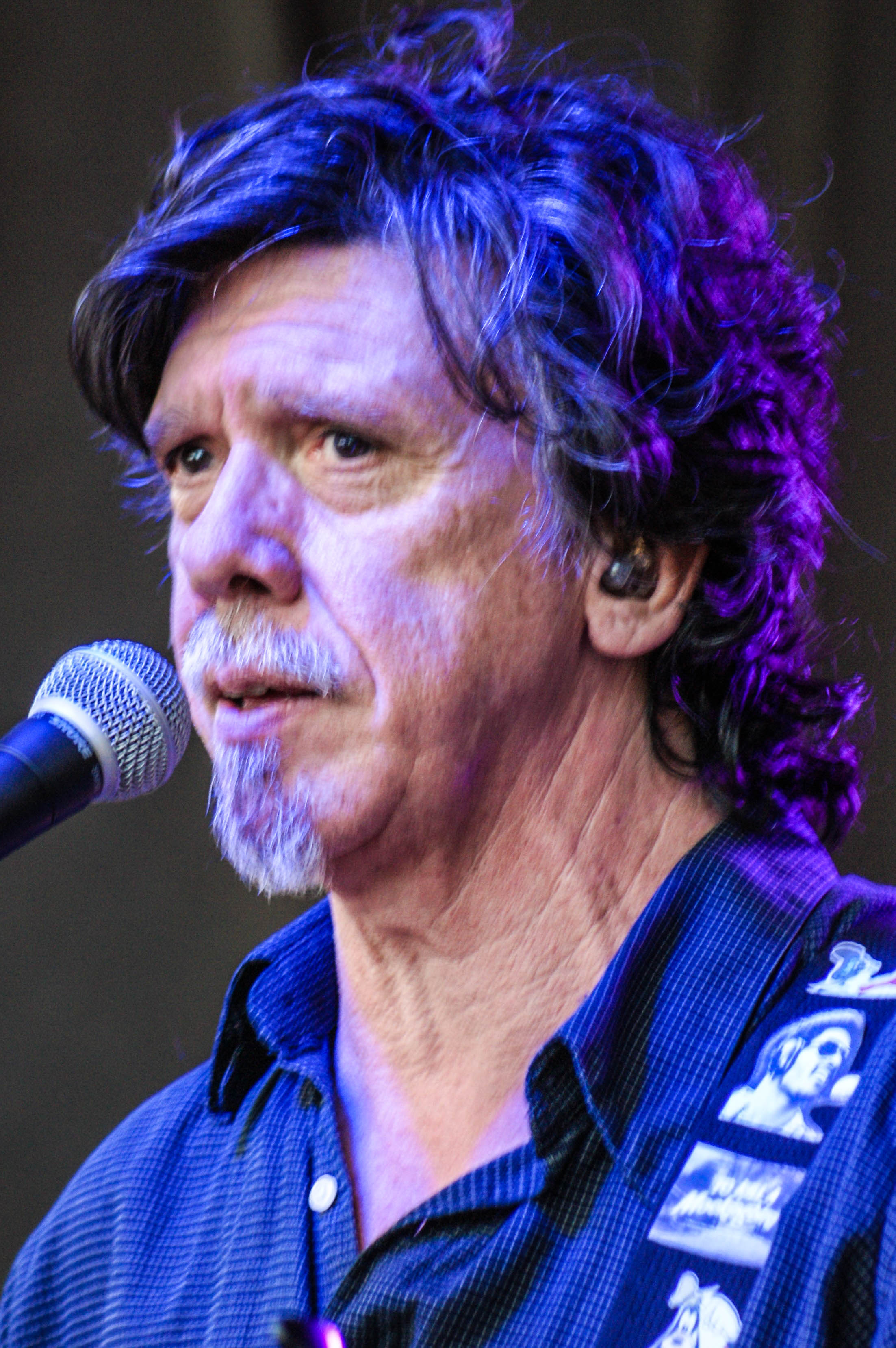

Johnson is quick to point out a Dead audience is unique. "Here's what I saw was the most miraculous thing about the Grateful Dead from a fanbase and from what the band did," he says, "was they created the most intelligent listening audience in pop culture. That skill is so refined that literally I can count on the fact the even in 'Stella Blue' where obviously the orchestra kind of deconstructs itself while all the time it embraces orchestral improvisation, I know the Deadheads can stay with me because they have spent their lives as fans, learning how to listen....Could you ask for anything more than that?"

Some will say that the Dead Symphony No. 6 is more like a suite than a symphony, but that may be splitting hairs. Some will say that Johnson is not a symphonist, and he does admit that, even though he has written eight. But he does assert, "I'm certainly comfortable enough to say I know what makes a symphony or not a symphony. Transcriptions are such perilous territory for orchestrators to go to. I didn't want to go as a composer into that realm unless it was no doubt the perfect moment for a symphony."

Johnson also reveals that even orchestras that seem to be constrained to the music on the page are also doing interpretation and improvisation. "Interpreting the work of the Grateful Dead is what the Dead did themselves. They reinterpreted themselves throughout, and all of them continued to do so," Johnson says. "By putting the notes on paper, the phenomenon appears to be kind of caught in the act. But symphonies, when they play things, also have nuance, and since I put in improvisation, they have to explore a what-if moment, too."

Johnson also reveals that even orchestras that seem to be constrained to the music on the page are also doing interpretation and improvisation. "Interpreting the work of the Grateful Dead is what the Dead did themselves. They reinterpreted themselves throughout, and all of them continued to do so," Johnson says. "By putting the notes on paper, the phenomenon appears to be kind of caught in the act. But symphonies, when they play things, also have nuance, and since I put in improvisation, they have to explore a what-if moment, too."

Orchestral improvisation is valid. "If you find yourself in love with a particular piece, and you go hear it from maestro to maestro or from recording to recording, your reaction is just undeniable. If I hear the wrong interpretation of a piece I really, really love, it's a physical response. You just go, 'Arghhhh.' Or if it's an epiphany, it's just the opposite. It's like, 'Oh, my gosh, I never thought that piece could be done like that!'"Johnson says. "That's just the language of spontaneity or the way spontaneity is translated in the orchestra. It is very tangible, but you just have to acquire some extensions to your ears to pick it all up."

Though a disc of the Dead Symphony No. 6 has been floating around for almost two years, the true test of Johnson's interpretation of Dead material will be found in the live orchestra experience in August.

Though a disc of the Dead Symphony No. 6 has been floating around for almost two years, the true test of Johnson's interpretation of Dead material will be found in the live orchestra experience in August.

"We took a lot of time to do this project because we wanted to do it right," Johnson says. "This effort is absolutely the best and most respectful and genuine offering that we could hope for. When it was approved by Grateful Dead productions, the publishers, Ice Nine, believe me, we felt validated in a huge way. The next process now is to see what the fans say or don't say.... I've done my part and now it's time for the Deadheads to speak."

The Dead Symphony No. 6 is worthy work by Lee Johnson. It is a unique contribution to both symphony and jam and is becoming a bridge between music enthusiasts of different genres and even those from different generations.