Within five minutes of speaking with Daniel Donato, I knew that the two of us would most likely have a difficult time keeping the conversation brief. Donato has the type of mind that makes me want to stay up all night talking well into the wee hours of the morning. He is the kind of guy who makes me want to start a podcast, or write a book. Carl Jung and his process of self-individuation, the 7 Hermetic Principles, all things philosophy, creativity, and spirituality— these topics light me up.

After our conversation last week, I think it’s safe to say that the same is true for him. In fact, I think it’s safe to say that Daniel Donato is always on fire with something.

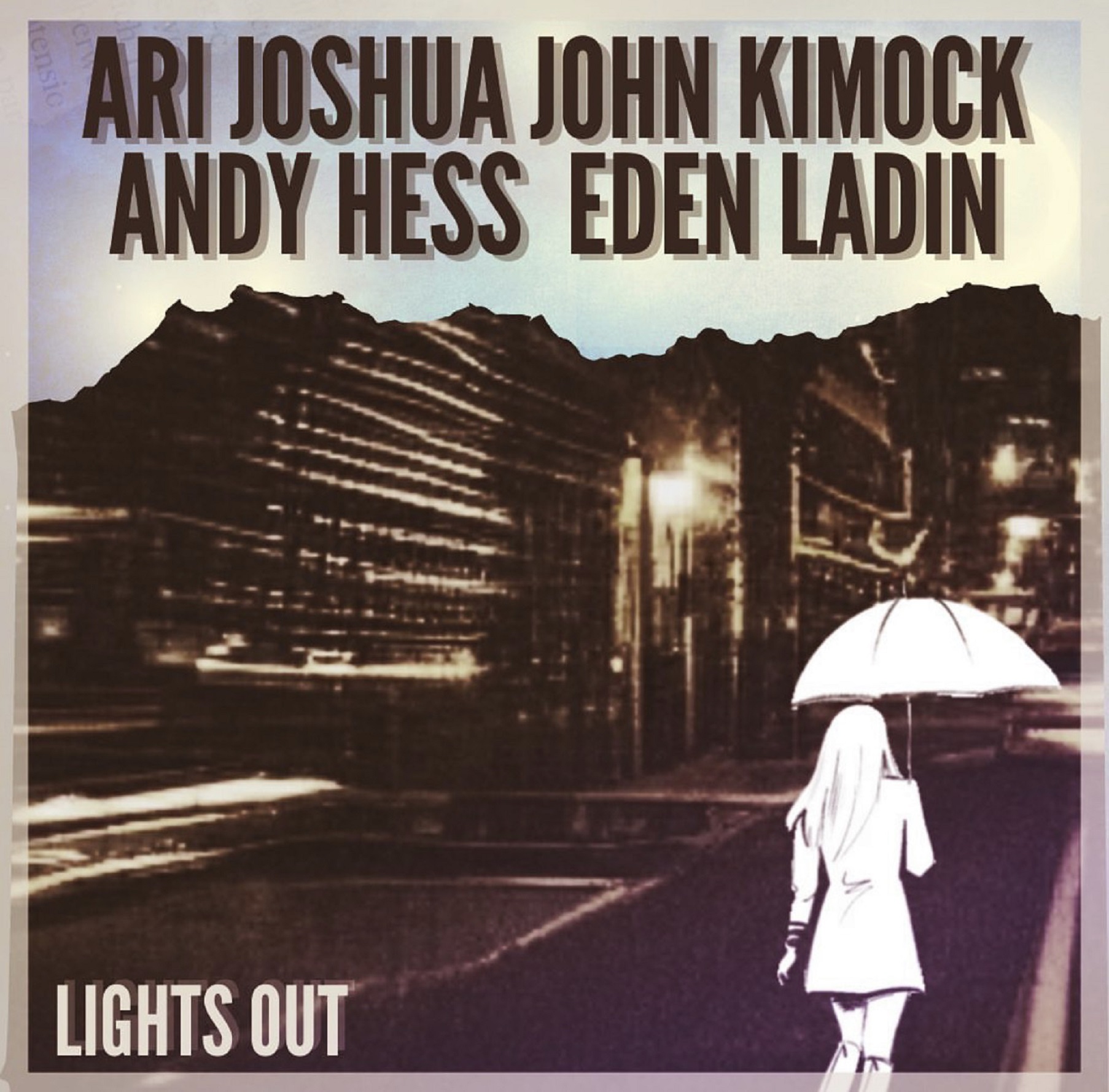

Most notably these days is his self-proclaimed “brainchild,” Cosmic Country.

Donato’s debut album, A Young Man’s Country was recorded at Nashville’s Sound Emporium in a mere two days. The record weaves outlaw country, Grateful Dead-style Americana, and first-rate songwriting into a singular form Donato calls “21st-century cosmic country.”

“Ain’t Living Long Like This,” one of three covers on the album, is a song by Waylon Jennings, who was recording at the Sound Emporium the day Donato was born. “Angel From Montgomery,” a song Donato learned on the fly while busking for tourists, pays tribute to the late John Prine. Donato recorded his unique take on the tune before Prine’s death. The Grateful Dead’s “Fire On The Mountain '' is tacked on to “Meet Me In Dallas,” a tune Donato wrote while on the road with Paul Cauthen. The other seven songs, all originals, showcase the promise of a young songwriter coming into his own, one of the highlights being “Luck of the Draw.”

Trouble No More, which includes Daniel Donato, along with Brandon “Taz” Niederauer, Lamar Williams Jr., Nikki Glaspie, Roosevelt Collier, Dylan Niederauer, and Peter Levin, will be performing The Allman Brothers’ iconic album Eat a Peach on Friday, January 6th at Boulder Theater, and on Saturday, January 7th at Cervantes' Masterpiece Ballroom in Denver.

Trouble No More will be joined by Daniel Donato’s Cosmic Country.

![]()

Read on below for an in-depth look into the fascinating musings of Daniel Donato, as he and I from Grateful Web discuss Grateful Dead, the importance of truth, and everything in between.

GW: I always start my interview days by listening to the music of whoever I am interviewing. The head space that it puts me in varies from interview to interview, but I feel like it helps me connect with the musician I am talking to. I started the day by listening to A Young Man’s Country. I also listened to Trouble No More live at Salvage Station, I believe? I have been having such a good time, and have been so lost in the music that I have barely taken any notes, which is great. When did you play at Salvage Station? How was that?

DD: “You know, you bring up a very funny point that I've been thinking about with music. As you get farther and farther away from events and records, the time in which they came out, or happened seems to dwindle in terms of importance. I don't remember the day American Beauty came out, but I know it came out sometime, and that's the thing about music. We're making a record right now, and I was saying to the guys before we went into the studio that, ‘every great album or piece of art should be perfect for its time, it should be ahead of its time, and over time it should transcend time itself.’”

GW: It should be timeless.

DD: “That's the idea. Music is one of the only energy sources that, in a literal sense, and also in a rational sense, is timeless. It creates time itself as it enters into our reality, so it would make sense that it has the potential to be timeless. And that is awesome. Thank you for listening to the record today, as well as the performance.”

GW: Can you describe in as vivid detail as possible, what it is like to be a part of Trouble No More and Cosmic Country? How are those two projects different in terms of what it feels like?

DD: “It is easier to describe what's going on with Trouble No More, and then explaining Cosmic Country. Trouble No More is almost like I'm stepping into a major league baseball team of some kind. When I was twelve years old, I was obsessed for months over ‘Jessica,’ ‘Melissa,’ and ‘Blue Sky’ [from Allman Brothers Band]. My God, I just loved those recordings, and I didn't know why. The entire business infrastructure of Allman Brothers Band is the supporting foundation behind Trouble No More. Bert Holman, who used to be the manager [of Allman Brothers Band] comes out to a lot of our shows. And CJ Strock, who worked with Allman Brothers Band for over two decades. So it is like getting to be on a major league Allman Brothers team of some kind, in a very imaginative sense. That's what's going on there, and that's marvelous. There's no original composition there. It's all just taking the catalog, and bringing it back to life, and playing it in a way that is slightly different than the Allman Brothers would do it. We are trying to hit a bull's eye that has already been hit at a certain point in time. Now, that's great fun, and it is very fulfilling, and it is a lot of hard work, which is great. It teaches any musician who wants to partake in a trip that has any influence of American rock and roll whatsoever— it behooves you to learn the nuts and bolts of the Allman Brothers catalog. There's a lot going on there, particularly the differences between Dickey Betts and Gregg Allman (and Duane Allman’s) approach to composition. Dickey Betts— and I'll die on this hill— is one of the best composers who plays electric guitar that America has ever heard. He has a signature touch to his approach, and it has influenced Cosmic Country a lot. So now we can move it over to what it’s like with Cosmic Country. The thing about Cosmic Country is that it is a trip that is being born completely from my own mind, and from my band. It is unexplored territory a lot of the time, which is quite different from the Allman Brothers project. It is my whole brainchild. It is all I think about, and all I really invest my time in outside of Trouble No More. It is a very asymmetrical part of my life right now. That's all I do (laughs). And the great thing about bringing it to Colorado, and playing there in January, is that it seems like there's no better place in America where an audience is more ready to receive and reciprocate energy than in Colorado, when it comes to live music.”

GW: So coming from someone who has never been to a Cosmic Country show, I am curious about what it would feel like to be there in the audience, exchanging that energy?

DD: “I hope it feels very real. I have been to so many shows in my life, and the best shows that I have been to are the ones that I can remember long after they happen. They always seem to compound whatever it is that I am feeling on the emotional spectrum of life. And just to make it simple, you could have a yin and yang of happy vs. sad. Sometimes you go to a show, and it brings this very deep emotion out of you that might be ultimately sad. And then, when you're done with the show, you find yourself back in the middle of the peace and harmony of both. Sometimes you go to a show and you're there with friends, or you're not there with friends, and you're dancing, and you lose yourself in a song, or you may not even know what the song is. You lose your mind in a song, and then you find yourself, and all that is wrong in life, and it brings you into this ultimate happy polarized state of, this is the best feeling ever. And then it brings you back into the middle. That's what I want. I want our shows to be as real as they can be. That's what I feel is very real. It doesn't seem like life is one-sided. It seems like you go from the polarity of happiness, to the polarity of sadness, and then you hopefully find yourself back in the middle. A state which allows you to go about your life in a harmonized manner. If our shows can help create that energy, both mentally and physically, then that's the deal for me. And that whole thing might sound very hippy and abstract, but I don’t think those kinds of thoughts and philosophies are as abstract as people think they are.”

GW: That actually makes so much sense. This concept of “liminal space” has been rolling around my brain for three years, and I didn’t really know why until recently. I had a sense that my role or purpose had something to do with the creative potential that exists in the in-between spaces, but I am just now starting to see this idea actualize, in a more tangible sense. It is a complete departure from polarity. I suddenly have a very clear vision of what all of it means, as it relates to my own life.

DD: “I guess that's what it's all about. That seems to be what this whole trip is. If you have this vision of what can be, then you have a much better time in the process of becoming. It seems to me that living equals becoming. That's all we're doing is becoming something. While we are also already fully realized in some sort of metaphysical part of ourselves, our whole deal is that we are always becoming. We are always changing. It seems to me that the more of a vision that you can have for the future, the more it directly influences the process of becoming. And that's the great prospect that America has given to its residents and civilians. One of my English teachers in high school, one of my two favorite teachers from high school, gave me a book called The Way to Wealth by Benjamin Franklin. One of the things Benjamin Franklin talked about is the importance of having a vision for the future, one that is much more ideal than what you have now, and to hold that in your heart with a faith that is equal to any proper down religion of any kind. A sensation of feeling and believing. And do you live in a place where you have the freedom to pursue that? Yeah, and that is amazing. And that's what Cosmic Country is for me, and that's what Liminal Space is for you. And that's why I love connecting on that level. So thank you for sharing that with me. That's beautiful.”

GW: That is what the past few years of my life have been about. Getting clear on my vision. Shedding layers. Getting crystal clear on who I am, and what I want. And what I want is to spend all day reading, writing, researching, and discussing art and music. I just want to eat, breathe, and sleep all of that (laughs).

DD: “That's why I love doing the Lost Highway Podcast. I love just talking about things. My God! You learn so much just through Improvisationally speaking. That's a lot of what the music is for Cosmic Country. A lot of it is improvised, and you learn a lot through improvisation. The podcast is a similar platform, because a large percentage of it is improvisationally having a dialogical conversation. Even if it's just you on the microphone, it is dialogical in some way. You are speaking to a listener, and so I very much can relate to wanting to research, speak, and discover at the same time.”

GW: So is the Lost Highway Podcast something you are taking a break from? Any plans to ramp that back up?

DD: “This year was a big year of growth for me, the band, our crew, and really just our whole team. I ultimately wasn't born to be a podcaster, so I had to realign my values internally. It’s not that the The Lost Highway podcast is done, it's just a matter of when I can have a producer for it, and when it can be more of an automated process of editing, offloading, and distributing. Also, curating guests. That'll be it. If it's just me, it will take up way too much time, and then my music suffers and that can't be happening. So that's an easy fix. Podcasts aren't going anywhere. Year after year, they keep growing. It is one of the fastest growing media platforms, which is actually really good because it totally dispels the belief that people have short attention spans. We have incredibly long attention spans. What we have is short consideration spans. We are given so many opportunities, and so much content to engage with. More so than ever. We have so many outlets. Our consideration span for what we like is actually very short, but our attention span is marvelous. People send me messages all the time like, ‘I listened to six hours of Cosmic Country today,’ so it is clearly not our attention spans that are short, it's what we consider important enough to actually give our long attention span to. The Lost Highway podcast will be back in action when I can find the right people to delegate some responsibilities to on the production side. And I would love to have you on it. One day we could talk about Nebraska. Do you ever turn on Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Nebraska,’ and drive around?

GW: No, I should. Oh, my God. There are definitely challenges to living here, but there are also a lot of great things about living here too. As a creative person, Nebraska is untapped territory in a lot of ways.

DD: “You haven’t done that yet?! Springsteen went to Lincoln, and I don't know if he recorded it there, but I think he wrote a lot of it there, and it sounds the way Nebraska feels. I like it. I've driven to Nebraska, and I love it. I love driving through there. It's very recharging. It's very American. I grew up in a town that was very much like that place. Its value centers on having a continuity of identity, and also an approach to creativity. Spring Hill, Tennessee, which is an hour south of Nashville. If you don’t fit right down the middle, not only do the kids not know what to do with you, the staffing at school doesn’t really know what to do with you either. It can be a trip for a young person. That's where I think one of those Hermetic principles is so fascinating: ‘as above, so below.’ It seems like this is where the whole American ideal is such a genius idea in many ways. The more you realize and perpetuate the individuation of your own identity, and your own trip in life— it seems that the frequency and overtones of you living your life in that way is heroic and true enough to inspire others to do the same thing. The more that you do right by yourself, in a way that is equitable and not selfish, of course, it actually inspires other people to live their life in a similar fashion, and that creates the opportunity for this value structure to compound and emerge in many people's trips in life. And that's the deal.

GW: Did you have anyone who modeled this for you when you were growing up?

DD: Mr. Chester, my English teacher. I think I had him for three years as an English teacher. He and Mr. Anglin, my history teacher, were some of the most influential teachers, in terms of schooling. He [Mr. Chester] showed up every day in a three-piece suit with John Lennon looking rimmed glasses. He would listen to John Coltrane every morning, in the middle of Spring Hill, Tennessee. Not a lot of people knew what to make of that guy, but I did. We got along really well. And he would always tell us, ‘Listen, guys. You can be Tennessee Williams. You can read John Steinbeck. You can read Jack Kerouac. You can read Virginia Woolf. These people are all using the same language. But how? How is everyone so incredibly different? How is that so?’ He would say, ‘When you give me your papers, I'm not just judging you on how much you know in a literary sense, or how correct you are, I'm judging you on your individuality. I am judging you based on whether or not I can tell who is writing by their individualized voice. He would always give me an A plus on my voice. He would write it in Red Sharpie: ‘True Voice.’ That was just so inspiring to me.”

GW: Wow. I love that. One of my students gave me the best compliments last year when he said, “You know Ms. Dollar. We can really just be ourselves here.” Made my whole year.

DD: “That's amazing. I think we really have a dying, burning, urgent responsibility to be ourselves. I don't think it's a luxury, or something that you do on the weekend. I think it's something that we have an urgent responsibility to do at all times.”

GW: It seems that you are familiar with Carl Jung. In my experience— from knowing, befriending, and dating a lot of musicians and other creatives, it seems to be extra challenging for creative types, so to speak, to find the balance between the feminine and masculine. Maybe since creativity and creative flow is so feminine, but it seems difficult, particularly for male creatives, to integrate their masculine in healthy ways. And speaking for myself, I had to spend a lot of years in my masculine— working, achieving, succeeding, building, and it was only fairly recently that I discovered the importance of embodying the feminine more, so that I could healthily integrate both. Can you relate to that at all? Have you found that to be challenging as well?

DD: “Oh, yeah. God, what a challenge it is. As it should be. You know it was Carl Jung who said, ‘Suffer well.’ The arc of personality is, I think, the only measurable field in a human's life that doesn't stop developing. Our body stops developing; our frontal cortex stops developing; and we do actually start to experience atrophy at a certain level. We do physically experience atrophy, to the point that a physical being ceases to operate at a certain place in space and time, inevitably. And that seems to be the case with 100% accuracy for any mortal that's ever walked this planet, so far as we can tell. You're going to die, but the personality doesn't stop developing, and so the whole concept is that one of the prime goals for a male is to integrate his feminine, otherwise known as the ‘anima’ into his personality. And a female can do the same thing in the arc of her life, which is to integrate her ‘animus’ into her life as much as she can, so she too can get the yin and yang harmony going. And that's what a lot of this deal seems to be for me. It's the trip, man. I would be surprised if you met anybody who was inquisitive, and who wanted to fulfill the adventure of that, and they were to say that it was an easy time. I just don't think I'd believe them. And thank God, it's not an easy time. We don't want an easy trip, I don’t think. That's why I don't buy it when people say they want to be happy. I think people actually want meaning, and meaning implies that there's a lot of shit that hits the fan, and that things can go very sideways, and that you actually embrace just as much darkness as you do light in life. So, yeah. It is tough for me. All of that is incredibly challenging, all of the time. So much so.”

GW: And what does that look like in your life? The challenge of integration.

DD: “I was on my couch last night, thinking about some of the things coming up this year. Some things that are incredibly challenging. One of the hardest things in my life is to figure out the balance of all these things, especially touring with 6 guys all the time. The more that we're on the road together, the more that it gets to be incredibly masculine. I'm always trying to bring everyone back to the center in some way, and so does Peter Levin, our keyboard player. He does an amazing job at this. He's one of the most integrated gentlemen who I've ever had the pleasure to work with, or be a brother too. He just naturally figures that out, but he's also a Cancer. I'm an Aries, so I have a very hard time integrating the feminine. My mom would agree, and some of my ex-girlfriends would agree too. If you read it, and open yourself to these kinds of things, it really opens your mind in such a marvelous way to how things could be. I could talk to you about Carl Jung all day. He inspires me just as much as Jimi Hendrix inspires me.”

GW: So I read in an interview that one of your teachers gave you some Grateful Dead bootlegs? Can you tell me about that?

DD: “Yeah, Mr. Raglan. My American History teacher. I don't know if he realized, but that was the biggest lesson in American history he ever gave me. 1968-1995 bootlegs. I am so grateful for that. Honestly, if this country sticks around and we keep developing on this great experiment of self-governance, which I think is an amazing idea in this part of the world, is to have this great Garden of America be revitalized, and brought back to where it could and can be, but the Grateful Dead epitomize that in terms of musical exploration, more than any other American act has ever had the ability to do. So, continuing along the lines of Carl Jung’s process of self-individuation: The Grateful Dead did that very well. They were very much themselves. And they had every facet locked down to a respectable degree. They had the music locked down. They had the community locked down. And they had the business side locked down. So yeah, I don't know if he [Mr. Raglan] realized that he was giving me the greatest lesson in American history that I could ever ask to have received.”

GW: So how exactly did that transpire?

DD: “That was a crazy time. I was playing down at Robert's Western World, which is one of the last honky-tonks in Nashville. Really, it was one of the first ones. Roberts is special, and it changed my life. I started playing there quite often when I was around 16, 17, 18, and 19, and one day, when I was 17, Mr. Raglan came by, and watched me play. I didn't know this because he was very low key. He's very extroverted and on top of his job when you're in the classroom with him, and he's running the show, which is great, but outside of the classroom, he was very respectable and formidable, and professional. So, I didn't notice that he was at the gig that night. He came by, saw me play some songs that the Dead played, and I guess he had the notion to give me his entire bootleg collection, and some of the non-boot official releases too. The Pizza Tapes with “Dawg” and Tony Rice. Legion of Mary. Rehearsal tapes. Reckoning, live and acoustic at Radio City. Sunshine Daydream, live in Veneta, Oregon. And then in Europe. All 16 volumes, or whatever it is. This was a Wednesday, because I remember I would always get a fried bologna sandwich on Thursdays before I would start gigging at Roberts, and I remember the day after he came to see me play, we were talking about Abe Lincoln. I remember this very well. After he finished the slide, he said in front of everyone, ‘Donato, see me after class,’ as if I am in trouble. I did very well in high school. I had a 4.7 G.P.A, and took all AP classes. I was very on top of my education because I thought I was going to go to school for music law. Everybody was telling me that I needed to be a lawyer growing up, since I love to argue. So that’s good if you’re a lawyer, I guess, but that's not my schtick. But I still wanted to do well, just in case. So I think, surely it's not a behavioral thing. I go stay after class to see what it’s about, and he hands me a binder that must be stacked 10 inches high, full of CDs, and he goes, ‘I need you to take these CD’s, listen to all of them in order, because they're ordered specifically for a reason, and never bring them back to me again.’ I was like, ‘okay, whatever, what's his deal?’ And so I open the binder, and the first thing I see is Dick's Picks Volume I, and I have no context of what Dick's Picks is. I'm showing my friends like, ‘Guys, Raglan just gave me a CD that says Dick Picks on it. Should I bring this to the principal? Is there something going on here? (laughs). Fortunately, I didn't. So I drove to the gig that night— and you know, I never really had girlfriends in high school that I went to school with. No one got me in high school. I was such a weirdo, and fortunately so, but girls did not know what to make of me at all, and neither did most of my male friends— so, I remember putting these binders in my passenger seat, and they stayed in my car for years. They never left. There was never a girlfriend there, and there was never a best friend there. It was like the music was my friend, and it was my muse. It was my feminine and masculine input of energy. It was all that I listened to for a couple of years. It was traditional country music, bluegrass, western swing, and the Grateful Dead. I discovered so much. Like how do you take Johnny Cash's “Big River” and make it 6 minutes long? How do you take “El Paso” and bring it into the context of a whole set of playing it right after ‘Dark Star,’ or before ‘Eyes,’ and ‘Morning Dew’? And the theatrics of these songs— the powers that be set it up perfectly for me to take that information at that time. I can't thank Mr. Raglan enough for that. I don't know if any of this ever got back to him, by the way. He's so professional that he's never reached out in any way. I don't even know if he's still working at Independence High School, but I can't thank him enough. It totally changed the trajectory of my internal and external world.”

GW: That definitely sounds like divine intervention. So not only are you part of the Allman Brothers lineage, you are also very immersed in the Grateful Dead community too. It seems that you are very much a part of the roots of it all.

DD: “It's American music that we are trying to get at. These are people who have, I think, the right idea of what America can be and should be. There is a party element there, to this dichotomy of work and play, and now we live in this economy, in this society, that is all about work, but there is something right about the Grateful Dead trip. It takes a while to get to a place where you can just keep truckin’. These lyrics, you can live your whole life on them. I don't know what I'm going for, but I'm going for it for sure.”

GW: That is exactly how I feel about literature. You know, I was reading Chaucer to my students the other day, and there was a specific part that I was reading, and I could just tell that it was having an emotional impact on one of my students. I could just feel the truth of those words, and I knew that he was feeling the truth too. The same is true for anything. When something or someone is true, we know it and feel it.

DD: “My God, I can't agree with you enough on that. I'd love to evolve that a little more, too. There are three things that come to my mind there. The three types of truths, which are: personal truth, objective truth, and political truth. Personal truth seems to be something that is true to you, and your internal world. My sister was bit by a dog when she was a kid, and because of that, she hated dogs for years. Her personal truth was to hate dogs. Objectively speaking, which is almost like a quantitatively bulletproof cemented truth that you can't really change, that's one kind of truth as well. The objective truth. And then you have this thing that is quite terrifying, which is the political truth, which is the mandability and plasticity of truth being curated through dialogue. So the more you say it, the more it becomes real, which is very, potentially volatile, because we live in a society where a select group of people control the narrative on certain truths, and whatever they say goes. Doch Coin is a great example of that. Its value is based on whatever the dialogue is. And so the political truth might be that the Grateful Dead are a bunch of grilled-cheese-eating hippies, or that they're a bunch of potheads, and demonic LSD trippers, and a lot of people would think that's true. But then you might have a personal truth of it, which is completely different. And the objective truth is that they are one of the greatest American enterprises there ever was, both musically and communally speaking. I'm always looking at the truth through those 3 filters, and the thing that always rings most true to me is—- I pretty much just say screw the political truth a lot of the time with the way things are now; it's hard to trust any trickle-down source. The objective truth, or what seems to have always been, and always will be real. I think the Hermetic Principles seem to fall in line with that. And then my personal truth, which is the beacon dancing on the shore of the unconscious shores of our mind. The personal truth of what is real for you, and this is where teachers and mentors have helped me align myself with my personal truths. One of the other things I want to bring up is multivariate or multi-trait testing. You have different groups of people, who have different traits of personality, and if two people can somehow arrive at the same conclusion, then that means something is true. So say somebody who's, not politically speaking, but just in terms of any dichotomy, you know, one side of a right, and another who is on one side of a left, and they can agree on an observation of any kind, that means something is totally true. That's where great songs come into play, which goes back to the power of music, what we were talking about earlier. I think everybody can pretty much agree that ‘Canon in D’ is a nice relaxing piece of music. Or everybody can say that they have a Beatles song that they like. Those are the things that are worth aspiring to create and go for in life: these things that unite everybody. My God! When we were in my English class, man. We read several pieces of literature that I remember everybody in the class being moved by. People who were raised in different political backgrounds, religious upbringings, and from all kinds of different homes. We could all somehow agree that Lenny dying at the end Of Mice and Men was a completely tragic tale. Or that in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, there is something very adventurous about that. These are things that are worth aspiring to, and assigning the title of truth to. I think there are a core set of principles. There are a lot of things that are true, but I think there are a lot of things that are floating around in our world right now that are not true that we accept as truth. It is a very shadowy, snaky, slippery time to be talking about things that are true and not true.”

GW: This idea of “truth” and “real” gets back to your goals with Cosmic Country.

DD: “That was also the idea with Cosmic Country. I am trying to channel what is true at all points in time. I think the greatest thing that I've ever consciously said to myself, or the most important idea I have arrived at in life, is to always speak the truth at all costs, and see what happens. You might lose some people in the process, but then you probably had to. You might also end up inspiring people in ways that you could never have consciously imagined. And so that's the thing. I value the personal truth above anything else. I try to embrace and embody it as much as I can. I try to speak the truth, and play the truth, as much as I can. And that is a full time job, because sometimes it hurts. We were recording a song the other day, and we were probably nine takes in, and I knew it wasn't the right one, so I just had to say it. I was like, ‘Guys that's not it.’ And everyone's like ‘God, Daniel, it's good’. And I know personally that it is not. And there's a reason why, so I'm trusting that, and I'm speaking it. And then, sure enough, we went to cut it one more time, and everybody was flipping. They were bonkers. That was the take. So I say: speak the truth and see what happens, man. See how it goes. Serving your internal world on that level, really is the thing that is shaping your external reality at all points in space and time. Let the truth be the cement and the compounding energy for this entire trip of experience. Maybe that's just part of the whole idea. Is that it? You just speak your own truth and live your own way.”