Grateful Web recently had the privilege of catching up with classic rock bassist Jack Casady. The seventy-four-year-old Rock’n’Roll Hall of Famer was inducted with Jefferson Airplane, but his musician partnership with Jorma Kaukonen as the celebrated revival blues group Hot Tuna goes back even farther. Many of our readers know the history surrounding the beginnings of Tuna. Back in 1969, when the Airplane would take a break at classic venues such as Bill Graham’s Fillmore, Jorma and Jack [the core of Tuna] would stay onstage and reckon the blues of Reverend Gary Davis and Mississippi John Hurt.

Nearly fifty years later, the band continues resiliently in both acoustic and electric formations. Prior to kicking off Tuna’s summer electric tour (featuring Steve Kimock), Jack opened up to us about his beginnings playing clubs in Washington D.C., the unusual artistic freedom that The Airplane had from the beginning, his evolution as a bass luthier, and why band meetings aren’t necessarily such a great idea.

GW: First of all, thanks for taking the time to chat Jack. You've been a musical hero of mine since I was a kid when my Dad introduced me to Hot Tuna. He was at the Fillmore East back in 1969 for those formative performances between the Jefferson Airplane sets.

JC: A pleasure. And yes, I believe I was there too.

GW: [Laughs] We’re off to a great start. So, 2019 will mark fifty years of Hot Tuna. Let’s talk about the current electric trio.

JC: In playing electric as a trio with Justin Guip we’ve gone back to our electric trio roots. And for acoustic Hot Tuna, we’ve been doing a duo. It’s been a really interesting couple of years going back into that territory. The electric band brings out different dynamics. It’s been a lot of fun.

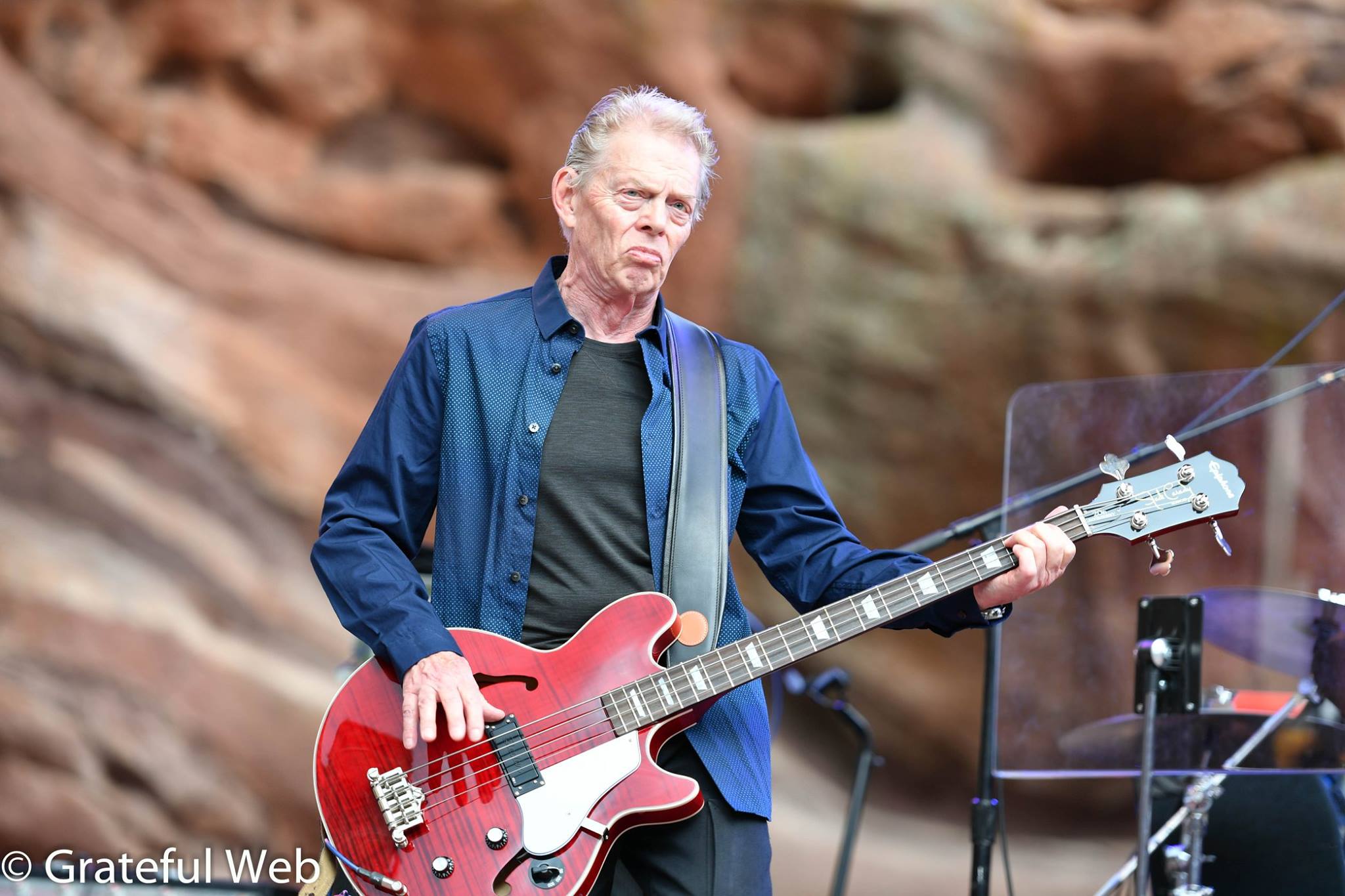

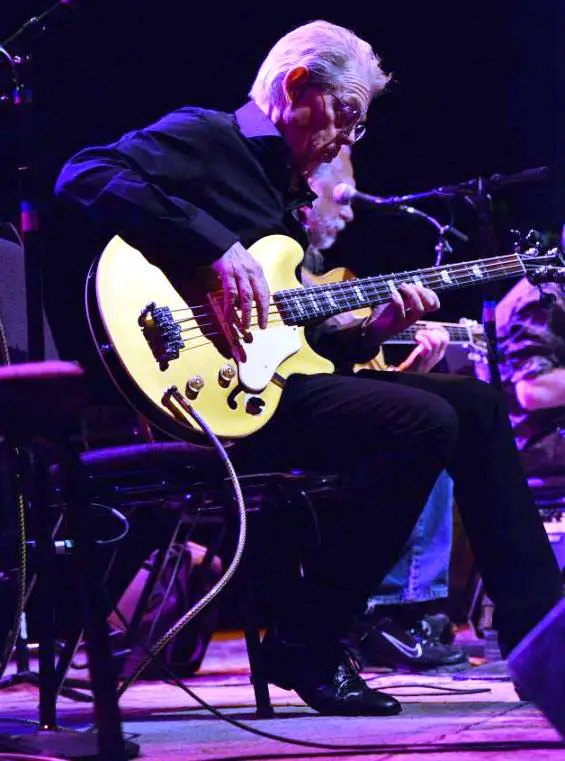

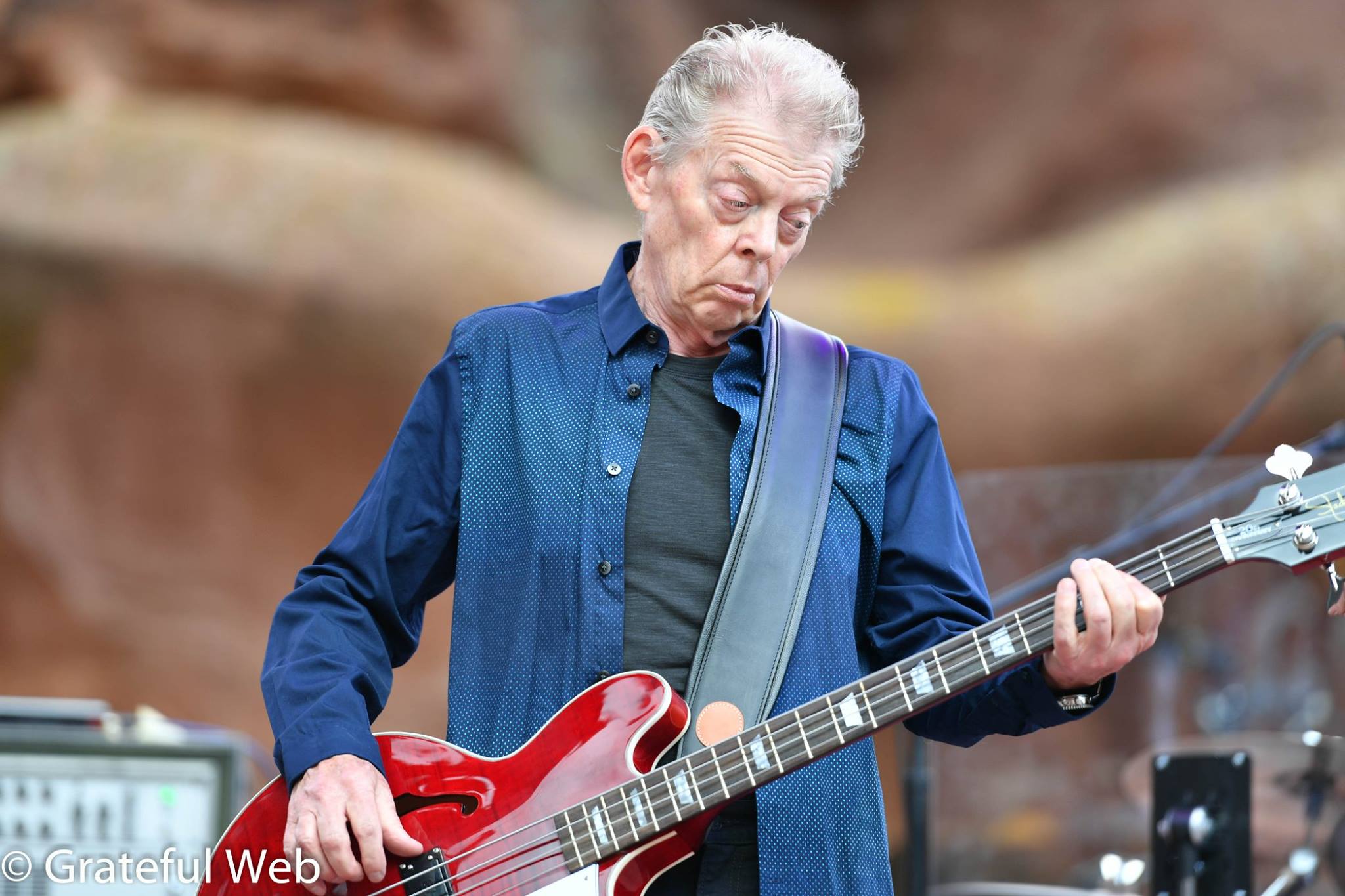

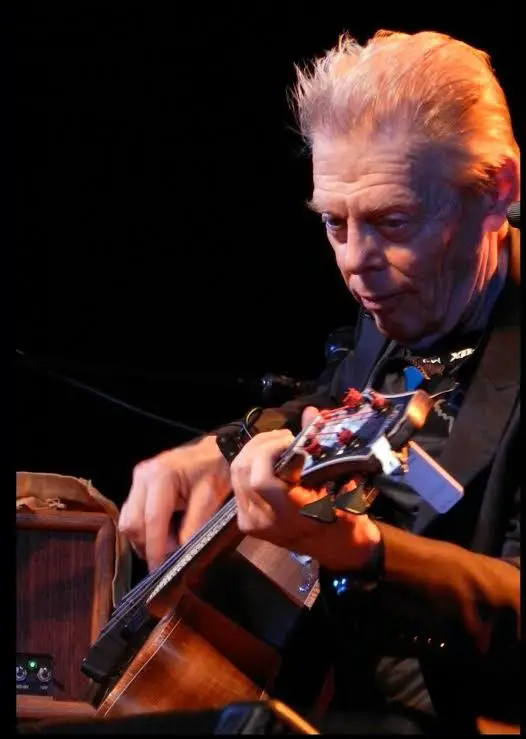

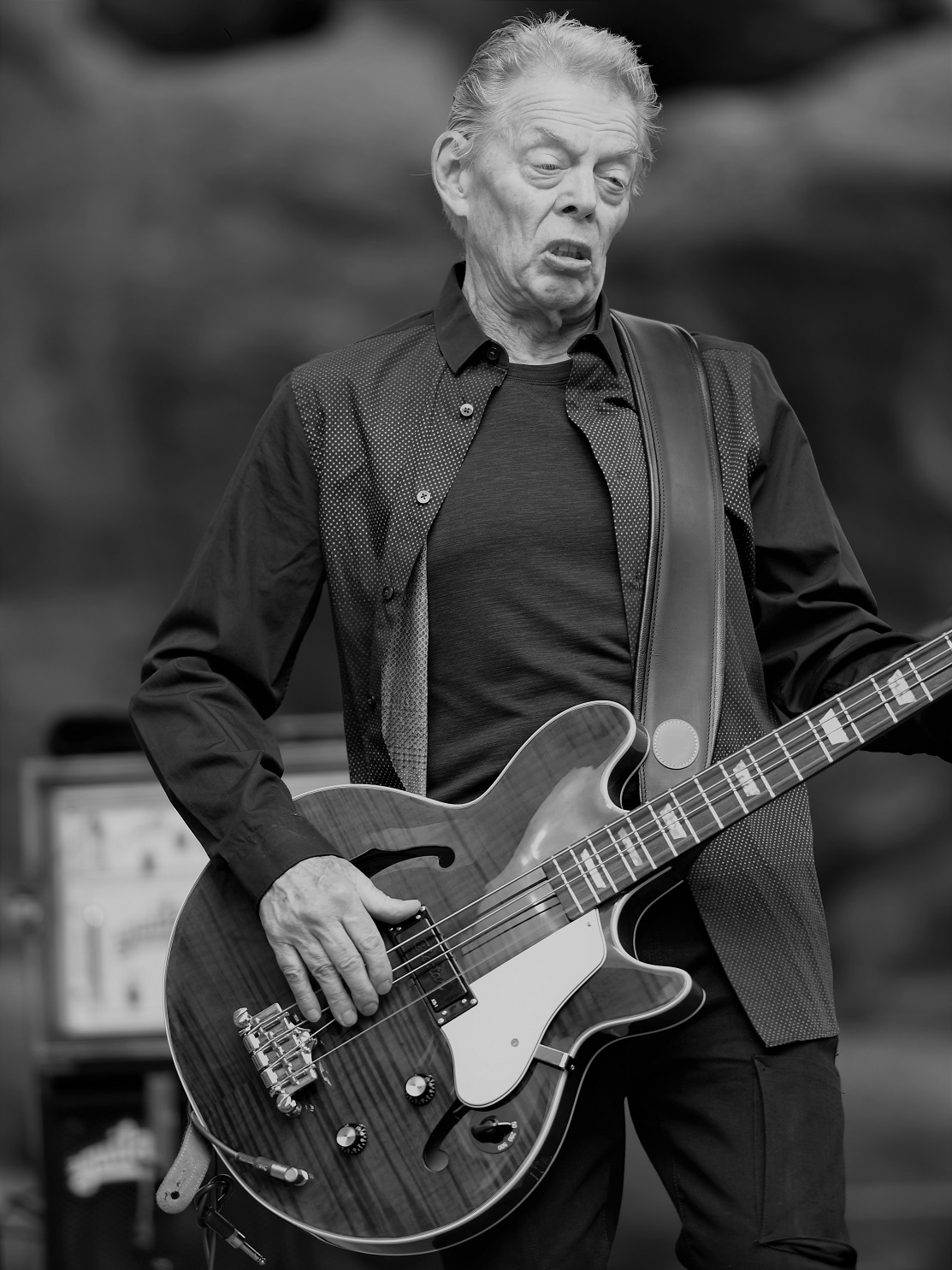

Jack Casady

Jack Casady

GW: That’s outstanding to hear. And this summer has you back with Steve Kimock in the electric band.

JC: Yes, we’ll be starting that run on August 25th at Nedfest in Colorado. We like to call it, Hot Tuna, The Trio, with Steve Kimock. He’s a really interesting fella. A real listeners musician. He adds these landscape sounds within the structure without disturbing the integrity of the trio. It’s not the same as a quartet with two guitars battling away for lead solos. He really does an interesting sound-scaping on his guitar. We have a lot of fun, and we’re happy he’s going to join us this summer.

GW: He’s a good fit. A nuanced player and a great listener as you noted. I wanted to ask you a few questions surrounding the beginnings of the band.

I know you, and Jorma Kaukonen were musical friends back in Washington D.C. long before the days of the Airplane. Do you recall when you were becoming acquainted with Jorma when it clicked that there was something special?

JC: I think musicians know immediately when they click with one and other. It’s the only art form that works like that. In playing music, there’s that hidden language. You can’t imagine two or three painters going up to the same canvas. There’s this language of opening up to each other’s vulnerabilities in order to make something else. Jorma and I had that right away, that was obvious and immediate. I was fourteen when I met Jorma. He was seventeen finishing out his final year of high school whereas I was finishing my final year of junior high school. Those are big age differences in those years. Somehow that didn’t really affect us at all.

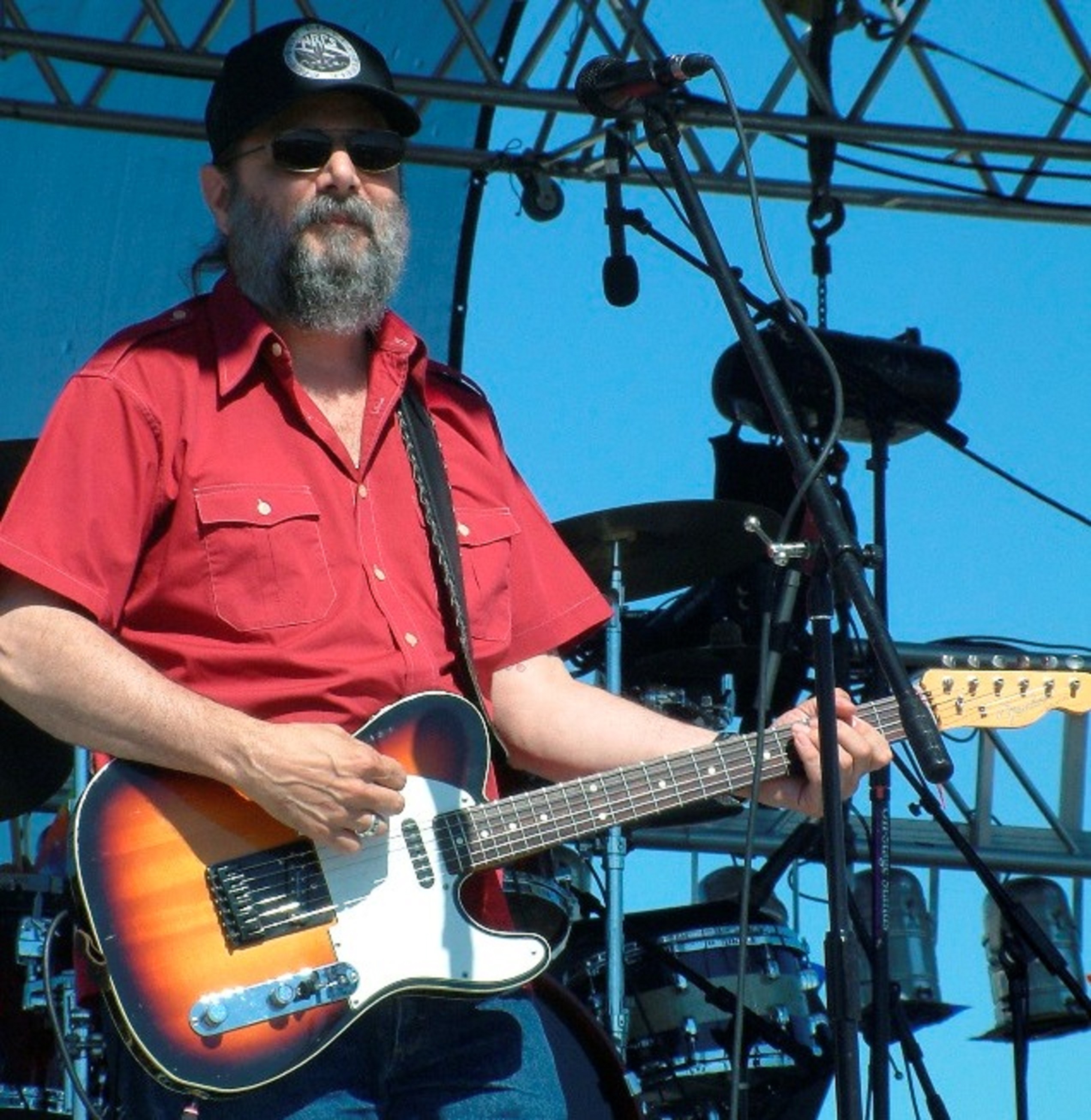

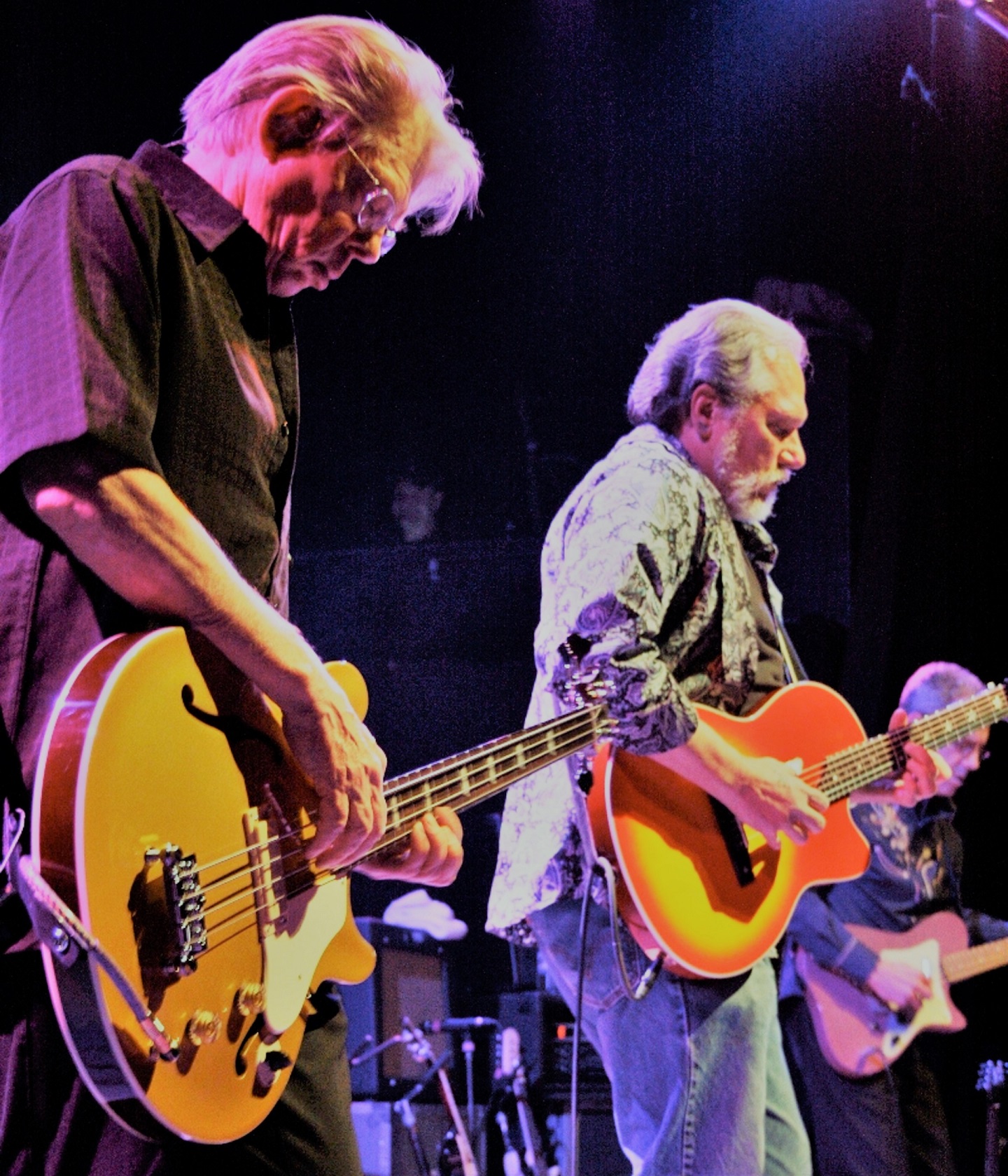

Jack and Jorma | Hot Tuna

Jack and Jorma | Hot Tuna

I met Jorma through my older brother Charles. We began sharing and listening to music, in particular guitar. I don’t think at the time we realized what was to be in the sense of forming that longer lasting musical relationship. It was easier to form the friendship first and then the common bond of music. As it developed a few years later, I knew this was what I wanted to do but didn’t quite know how I was going to go about it. Same as Jorma when he went to college the next year and started learning finger-picking and the folk approach, that’s when he realized this is what he wanted to do.

GW: It’s great to hear about those formative years as there’s so much emphasis put onto how you were both parts of Jefferson Airplane and the San Francisco Sound a few years later in The Bay Area.

JC: And the thing was we never really lost touch during those years between. When he went into a work-study program at Antioch College [Ohio] and then New York for a period of time, I went to visit him there. I was sixteen, took the train out, and we went to all the folk and blues clubs together and listened. We weren’t playing together then, but the first year he was back from Antioch he took me down to his basement and showed me his guitar and that approach. I thought it was just terrific and a really inspiring approach to guitar.

I went on in my musical direction playing in rhythm and blues bands and developing my style on bass guitar. That went on for a few years until 1965 came along when I was in my third year of college. Jorma and I had a conversation, and then I went out to San Francisco to join the Jefferson Airplane. It’s interesting how that worked out. I was in a position where I was playing in a lot of bands in the club circuit world in D.C., but I wasn’t in any musical conglomerate that was making its own music or mark. Clubs wanted you to play other people’s songs.

Jack and Jorma | Hot Tuna

Jack and Jorma | Hot Tuna

I had been listening to a lot of jazz and classical music, also country, Appalachian, and blues. I didn’t really have a vehicle to expand to the next level which is developing your own style and tone and songs to start writing. That’s where the Jefferson Airplane came in. For me, it was so timely because I didn’t have that vehicle and I was able to use a lot of stuff I had learned and begun applying it in different ways towards original songs.

GW: There was definitely a drastic difference between the rock ‘n’ roll of Chuck Berry and the 1950s when looking at what was manifesting in San Francisco around that time. Could you talk about your approach when melding with the Jefferson Airplane? How did it differ from how bass functioned in the rock‘n’roll previously?

JC: First of all, at the time the word psychedelia wasn’t even in my consciousness. The rock‘n’roll that I liked was that Chuck Berry stuff in addition to the rhythm and blues stuff which was a big influence on me. Ray Charles and Ike and Tina Turner and early Aretha Franklin. Most of those bands had horn sections, and things were charted out a lot more.

My other big influence was classical music and being in Washington D.C. I would go down to Constitution Hall and hear all the great names and musicians. I watched the cultural exchange program of the early 1960s brought on by Jackie and John Kennedy. I was able to watch the Russian ballet, the Bolshoi Ballet, and others. In the early 60s, the folk revival was where Bob Dylan, Dave Van Ronk, and the Holy Modal Rounders came out of, along with the rediscovery of musicians like Mississippi John Hurt. All that music was pouring through me.

Jack Casady

Jack Casady

In the early 60s, there were all the terrifically great jazz musicians. Roland Kirk, Eric Dolphy, John Coltrane, Wes Montgomery. All of these great players were coming into the jazz world making their own music. To me, it was a perfectly natural thing to apply influences. I mostly think of myself as a folk musician because a lot of my bass playing approach is applied towards songs. I really don’t like long-standing instrumental stuff as much as. I like having more of a well-written song and that framework to be creative in. That doesn’t mean I can’t take extensions or play some other landscape directions, but I loved vocal music, and I play off of the vocal all the time.

That’s why when I got with the Jefferson Airplane those three-part vocal harmonies were natural because they reminded me of the horn sections of rhythm and blues bands. But we also had that jazz extensions attitude towards the music. We had all these different writers within the Airplane, for instance, Marty Balin was a solo singer in the early sixties and had brought into the Airplane a professional vocal approach. Paul Kantner brought in his influences such as The Weavers and various combination vocal folk groups that he liked. He was behind those harmonies in the early albums, starting with Signe Anderson on the first album and then moving on with Grace Slick.

Grace brought into the band her classical background on the piano, and that song structure really was a comfortable form for me. The chordal song structure gave me a totally different approach with her songs that I would have applied with Signe, Paul, or Jorma. I was able to think differently with different writers, apply different directions, and really move into the songs. One of the things I brought from my influences whether it be classical, jazz, or folk, was great tone. I loved Charles Mingus’ tone on the bass. I wasn’t trying to play like him, but he’d play like the tone of soprano saxophone which was so powerful. I took those sensibilities with me to begin working in the Jefferson Airplane. The timing was just perfect.

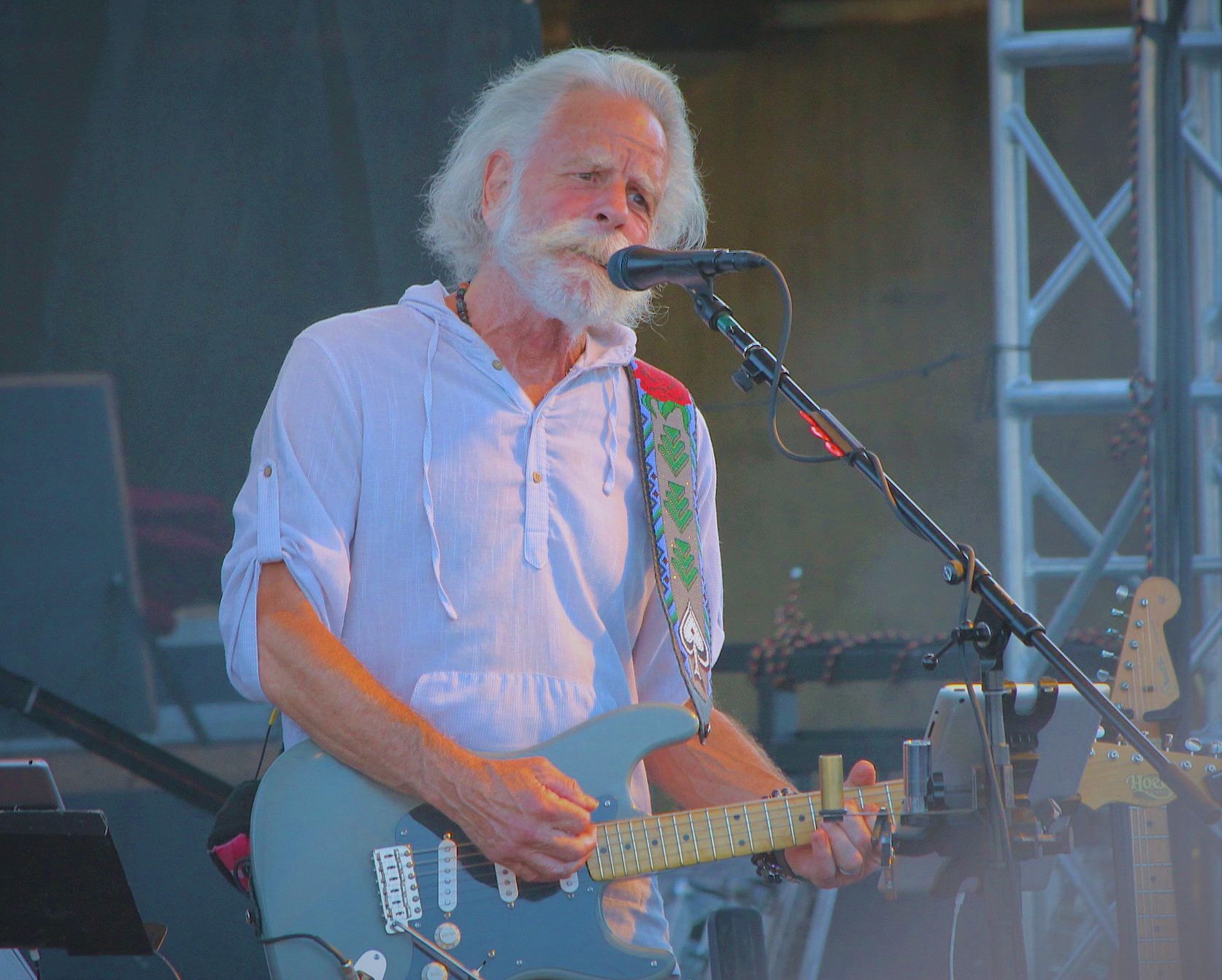

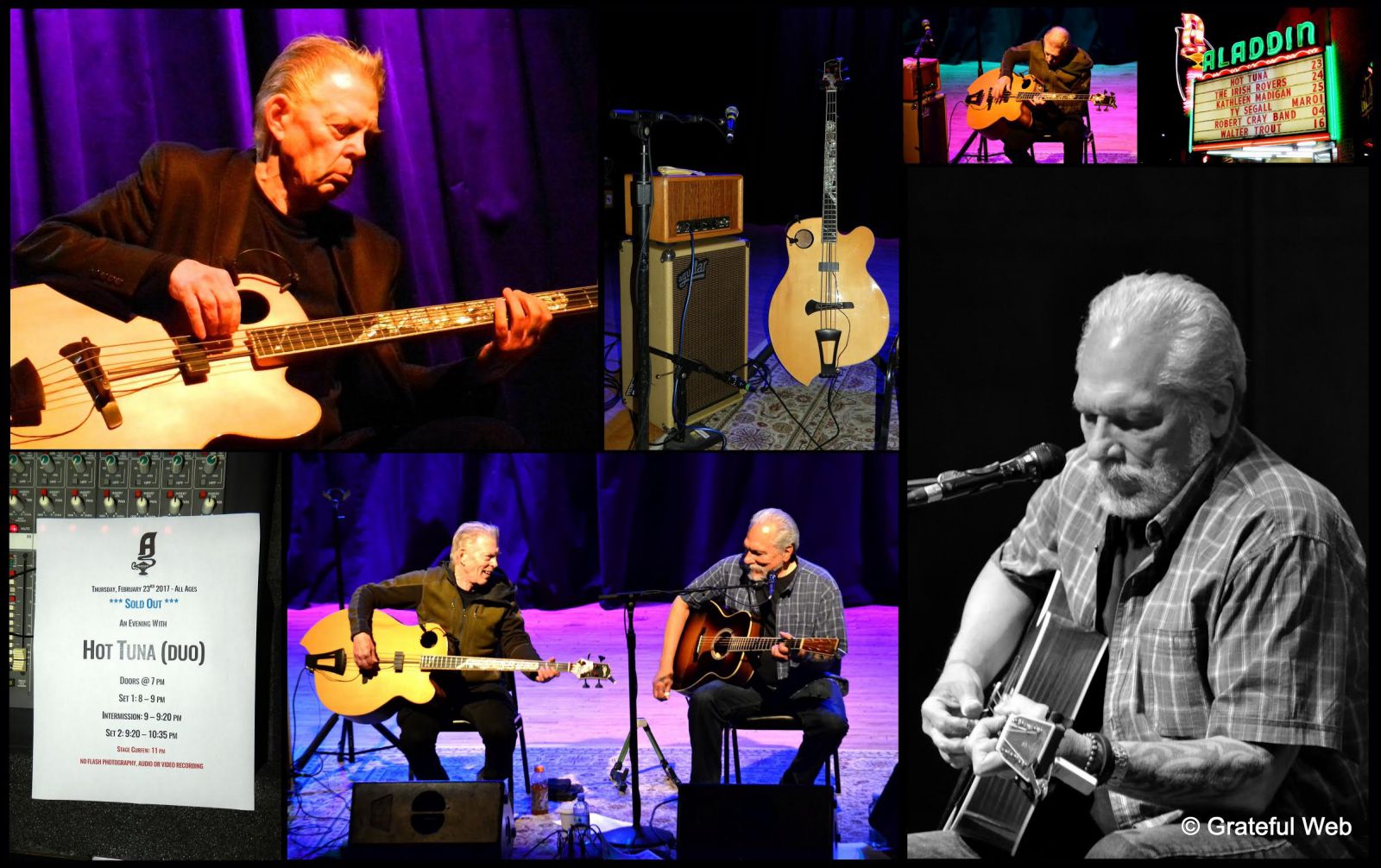

Hot Tuna | Red Rocks

Hot Tuna | Red Rocks

GW: It doesn’t sound like it gets much better than that, in a time when bands made stylistic compromises to get signed to record labels this sounded like the genesis of something that was really all of you.

JC: It was pretty much a difference of attitude. When more bands developed in San Francisco, it becomes an entity that was talked about. It was really the beginning of the antithesis of the polished pop approach, as the Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Nashville, or New York approach to a three-minute song. We loved good songs, but that pop approach didn’t necessarily fit into the format.

We lucked out with “White Rabbit,” coming out at two minutes and forty seconds. It wasn’t crafted by Grace to be a pop hit song. We never thought it would take off that way. But “Somebody To Love,” was a classic rock ‘n’ roll song that really moved well and had a great hook and all that to it. Even then, in the period of 1965, it didn’t necessarily fall into that formula. Later on, bands started to form down here to begin creating their own music. Gradually after some success, certain bands and people had a little more control over their own destiny. We would get more control in the studio.

GW: It’s insightful to hear that side of things. You hear the various horror stories from the early 1970s about record companies binding.

Jack and Jorma

Jack and Jorma

JC: That’s never been any different. Even today if you find a record company and they put a contract in front of you, it will likely be a horror show. Same with the first contract we had with The Airplane. We had some demands that were met which were very unusual at the time, but generally, in those first contracts you’re giving your life and soul away. We managed to get a good first contract but a much better second contract.

GW: What’s also interesting was all of the different influences and personalities behind the Airplane. It was definitely a collaborative effort.

JC: That was something I felt was very unusual. When I came out, we had all these musicians from different backgrounds and because you had all these different kinds of people with different tastes within the band that’s what worked in the beginning. Later on, it also became a little cumbersome. Don’t forget we were all young, developing our craft, and looking for our place and direction. We were doing that together in one band which is why I think it only lasted seven years. After a while, there was too much going on in one band, and we needed the time to focus individually.

That was what happened when Jorma and I left to form Hot Tuna; we wanted to concentrate on something different. And then we got together again with Grace, Paul, and Marty again to form Jefferson Starship. I look back on it, and it was a natural evolution.

Hot Tuna

Hot Tuna

GW: It’s very interesting from an audience perspective. Hot Tuna began as you and Jorma playing these deep blues cuts. Then you would play after Airplane gigs, always scouting new places. When you brought together Hot Tuna, was this just coming together to play what you loved?

JC: Yes. It was part of the alternative view of the way we made music in San Francisco. And we didn’t want to be road monsters. If you had a couple of hit songs, the record company would want you to go out on the road. Part of our view was in order to create new material you had to be home long enough to write it. If you’re on the road all the time, every song you write is going to be about being on the road [Laughs].

Jorma and I found ourselves with a lot of times to ourselves, and we started to very naturally play together the kind of music that was oriented with his finger-picking folk style. Then that developed into Jorma writing songs. We developed our own style of working within the blues, folk, and rock that was all mixed together. We’d bring a tiny little amplifier into hotel rooms, and I’d bring my bass. Later on, we started developing Tuna with drums and electric instruments. It always had the uniqueness of being in the finger-picking style, even with electric guitar. In that way, it was an unusual sound. Nobody had ever put together a bass and guitar together to play that kind of music.

GW: Hot Tuna was one-of-a-kind while reckoning the roots. Over the years, the band has existed in different iterations with diversely marvelous musicians bringing a fiddle, harmonica, mandolin, drums, and piano into the fold. With the journey of Hot Tuna nearing its fifty-year mark, what were some of the most unexpected intersections?

Jack Casady

Jack Casady

JC: What’s interesting is that all musicians want to get put in a space where they’re uncomfortable. The core of Hot Tuna is Jorma and Jack. As soon as you enter another element the rhythms change. Little things change within the music. You add another player- most recently Barry Mitterhoff. Before that when Papa John [Creach] came in, he had all the experience. Bonafide experience is playing fiddle in all these genres and styles. If you listen to his playing on an album of ours, like Burgers, you’d hear him fall so comfortably into that Piedmont blues stuff we did. Because that’s almost ragtime. The interchange in that band with Sammy Piazza and Papa John was great, and it was unique because other people didn’t approach it that way.

When we formed an electric Hot Tuna trio using high volume techniques and amplifiers, and we built another approach. Then we’d see ourselves over-doing that approach, so we’d add an additional musician to change it. The interplay and environment become different.

GW: Switching gears a little bit, you developed a signature bass guitar with Epiphone some years back. Clearly, it was designed from the way that you play and see the bass guitar. What was the inspiration behind the design? There’s a lot of big players using it out there.

JC: The inspiration really goes back to my father who was a dentist and an audiophile. Jorma & I would listen to the HiFi amplifier that he had set up in the basement. He had lots of music and belonged to the American Jazz Society, so we listened to music all the time. One thing he taught me was if you don’t like something, change it or build it better.

Jack Casady | photo by Michael Bachara

Jack Casady | photo by Michael Bachara

With that in my background, I started developing instruments. The Alembic Number One was developed with Rick Turner and Rob Wickersham in the early 70s. Before that, I took my Fender jazz bass, if you notice early pictures of me playing in Jefferson Airplane, added a third pickup and a precision pickup to provide more variety of sounds. When I started playing Guild Starfire basses, I worked on those extensively, the first one with Owsley Stanley who’d be doing the electronics and putting in filters. In the second with Rob, we developed more stability of sound. We developed the standalone from scratch bass in Alembic Number One.

In the early 1980s at Chelsey Guitars in New York, I discovered a hollow body Les Paul bass that Gibson put out in the early 1970s. I’d never played it or even heard of it. It had a great feel and sound to it. What was unique to it, was unlike a lot of electric instruments it didn’t have a center block all the way down. It had a footed piece going down the back. It had true acoustic space inside the instrument. I liked the sound but found it deficient in certain areas.

I approached our friend Mike Lawson, who worked with Gibson at the time, I spoke with him about a possible re-issue and allowing me to work on that style of bass. That run of hollow-bodied Les Paul basses was only for a couple of years in the early 70s, and then that was it. Gibson wasn’t interested, but they owned the company Epiphone, and Jim Rosenberg was interested in collaboratively redeveloping the bass from scratch. We took the measurements of the original Gibson instrument and developed the pickup system over a couple of weeks in Nashville with J.T. Riboloff. A year and a half later the instrument and the pickups came together in the way that I wanted. We put it out as the Jack Casady bass. I’m proud to say that amazingly twenty years later, it’s still here.

I try to maintain control of the quality, from every new manufacture run I get a couple to test out and take them right on the road. Right now, on the road, I’m playing the two Jack Casady anniversary basses. That’s how I test it out.

Jack & Jorma | Hot Tuna

Jack & Jorma | Hot Tuna

GW: It’s amazing as you and Jorma have fostered this beautiful friendship all these years and from at least the audience perspective there was never anything hindering the continuation of Hot Tuna. And the community access aspect of Tuna is noteworthy-

JC: It’s wonderful. And it spans so many age groups. I’d like to think that we have that wonderful, loyal community because of how we really feel about the music. We really do love it and love to play. We try to give our best shot every single night. That’s our path in life.

We played some shows at the beginning on March. Jorma and I looked at each other after playing a two-and-a-half-hour acoustic show and said, this is more fun than ever. Here we are sixty years later after we first met and began playing. Our relationship isn’t just based on the fact that we formed a band together. It’s based on something deeper. Jorma likes to joke that the reason we get along is that we never had a band meeting.

We did briefly stop playing at the end of the seventies really because we had saturated ourselves so much. Don’t forget we were with the Airplane for five years until 1970 then we just continued to saturate ourselves. There weren’t any dramatic fist fights or anything. Jorma went off on his own for a while. I formed the band SVT which played for a few years. Then we got back to play together in 1983. We just came back to playing because we played together well and enjoyed it so much.

Jack Casady | photo by Mike Moran

Jack Casady | photo by Mike Moran

In later years we appreciate it more than ever. In this last twenty-one years, Jorma’s manager and wife Vanessa started Fur Peace Ranch. I teach there three times a year and Jorma year-round. The teaching aspect has been so bonding and beneficial, to get with guitar players who want to join in on what we’ve learned over the years. And it’s such a great environment down in Southeast Ohio. Jorma and Vanessa worked hard to make a fun learning experience environment. That’s kept us sharp and alert with our craft work. We’ve kept it very real.

GW: Sounds about as good as it gets. The fans picking with the band and everybody becomes just another player.

JC: These are guitarists who want to learn how to play. Every great classical musician has said, if you stop learning, teach. It gets you inside that instrument to show others how you do things. Then you have to think about what you do and why you do. It only opens out. It never closes down.