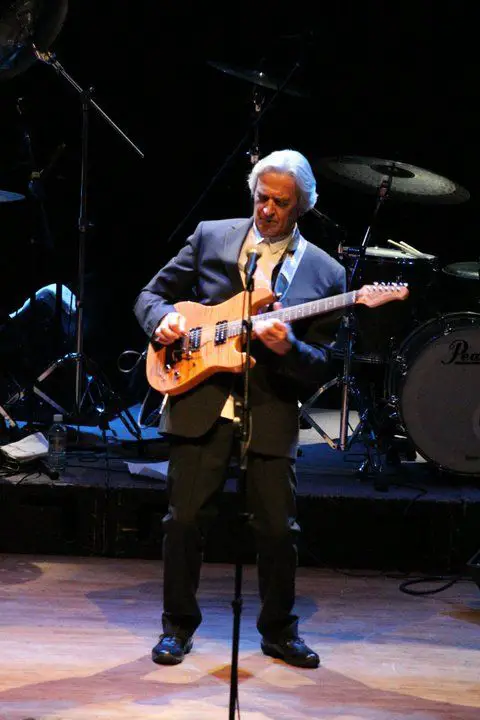

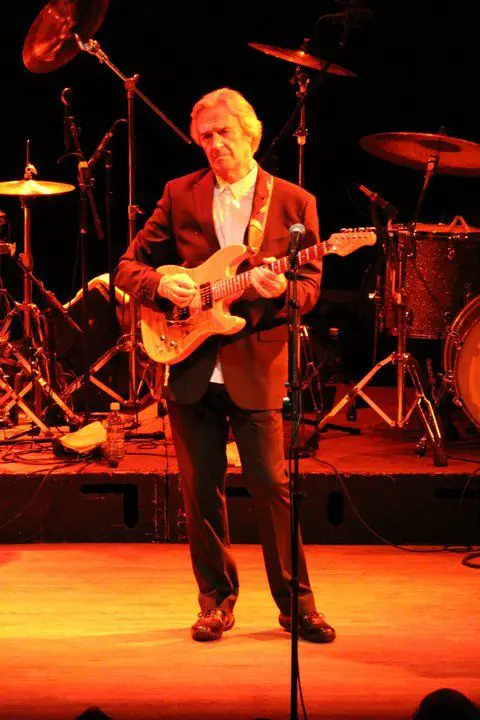

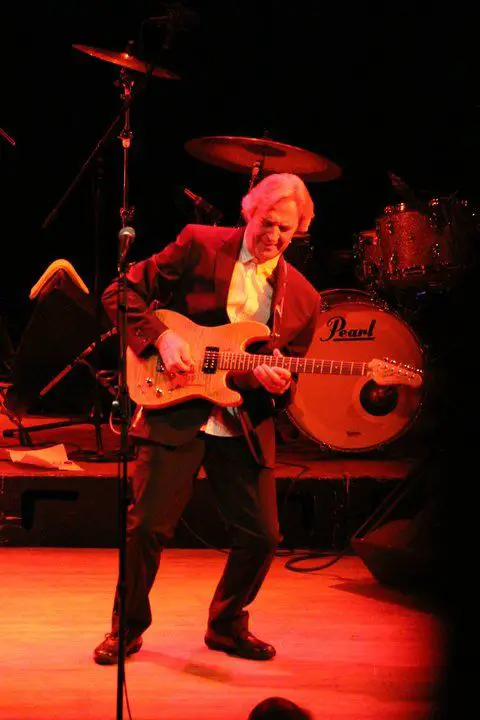

Grateful Web was humbled and honored to have an extended conversation with jazz-fusion guitarist and bandleader John McLaughlin. He began recording and composing groundbreaking music in the 1960s before joining forces with Miles Davis on his landmark albums “In A Silent Way” and “Bitches Brew”. His band Mahavishnu Orchestra was the fundamental jazz-fusion originator. His illustrious career since has been continually remarkable. In a recent interview with Dylan Muhlberg, the jazz icon opened up about his early affection for flamenco, principal Indian techniques within his compositions, and his newest personal statement Black Light, which is his third studio album with his awe-inspiring band The 4th Dimension.

GW: Thank you so much for joining me.

JM: What a marvelous introduction. I am humbled myself Dylan! [Laughs]

GW: A man like yourself needs such an introduction.

The musical journey of the 4th Dimension has been joyous for your fans and clearly for the band. What keeps you collaborating with these men?

JM: I love them. I love they way they play; they are marvelous musicians, and marvelous people too. When you have that combination in a band there’s a developed complicity. We’ve been in this particular formation for three years now. I don’t think I’ve ever played with a band this incredible. And don’t get me wrong; Mahavishu Orchestra, Shakti, and Remember Shakti were incredible also. But this particular band brings a certain spontaneous joy when we get together.

We are all thrilled to get to play together and what we have is pretty unique. When I speak about complicity, I’m talking about a particular understanding from knowing each other so well, how we provoke and stimulate each other, and go beyond what we know to discover the hidden pleasures inside. That’s what it’s all about. Does that make any sense Dylan [Laughs]?

GW: Yes! [Laughs] Of course it does. I’ve become keen on this particular project myself having been lucky enough to catch the a few rare 4th Dimension Colorado gigs.

I deeply adore how the four of you flow with a seamless synchronicity when you play. There are no soloists yet everyone must act as lead together. How has your musical relationship developed in this regard? Was it always so fluid?

JM: In a way it has always been that tight. While I brought this band together and financed the recordings, they need an opportunity to be who they really are and also to have the provocation to push them into places they haven’t been before. Improvisation is a spontaneous act and what you speak of when you improvise is really just the story of your life. We don’t really have any other story. It’s about the relationship we have with ourselves and the relationship we have with people.

If you’re surrounded by an atmosphere of admiration, acceptance, and stimulation then the spontaneity of improvisation can flourish. This is where we begin to discover ourselves. Then there’s our separate history. There’s so much in the subconscious that has happened to us. These events manifest themselves in a musical way.

GW: So is it that spontaneity of improvisation that yields your compositions?

JM: Not really. Improvisations are essentially spontaneous and they come like flowers. They come and they go. Recordings are captured.

Take our live album we released last year, The Boston Record. It’s a whole other ballgame. If you’re lucky you have a good night. If you’re lucky you have a good recording. We struck in lucky in Boston. I really like The Boston Record. It’s totally live and unaltered. That’s it. It’s mixed well and sounds good. The rest is the performance and the players. You can hear the whole atmosphere of our live performance.

In the studio with [Black Light] it was a bit more like a painting. In a way this is a follow up to a studio album I released a decade ago called Industrial Zen. I employed colors from sound design, atmospheres, and different sequences. There’s more color on this canvas, in the studio. The whole point of this record was to employ these colors, which is a whole different idea in the studio with our production team, with the live playing. You hear on the album the wonderful spontaneous playing. This integrates these causes and dimensions that I began exploring on Industrial Zen. There’s a dynamic space here that comes from this sound design. It wasn’t about capturing any specific notes but more of an atmosphere. There was about a year of production on this new album. These dimensions that we can create fascinate me.

GW: There are certain elements that Black Light focuses on with these sound design techniques that Industrial Zen just began to scratch the surface of. For instance Ranjit Barot’s konokal percussive vocalization techniques are stunning on the tracks “360 Flip” and “Kiki.” How has this sound design grown the possibilities for The 4th Dimension?

JM: Immeasurably, Dylan. Ranjit and I go back quite a ways. We played in India at the Abbaji Festival in Mumbai over a decade ago, which is a celebration led by Zakir Hussian, who has been a collaborator of mine since the early 1970s. Ranjit was one of the musicians I met there. He appeared on my album Floating Point, which was recorded in India. I brought in some of the young great Indian players who are as much into fusion as I am, without belittling or selling out one or another expression. Musicians from different cultures getting together and playing together does not lower the standard of the discipline that they normally operate under. During these recordings I decided he needed to be part of the 4th Dimension.

Konokal first entered my music on a piece called “Pandit,” referring to Pandit Ravi Shankar. I was very fortunate to study Indian music theory with him in the early 1970s. I was living in New York at the time and he would call me up and we would visit often. It was marvelous to spend time with the great master. One day he told me that he wanted to teach me konokal, which is a South Indian system of rhythm. He taught me this rhythmic theory and it was one of the blessings of my life. We lost him last year and he has been in my thoughts and music. It was so important to me that five years ago I released an educational DVD about konokal mastery. It’s a marvelous system to communicate rhythmic phrase between musicians. If you can sing it to them they understand immediately what it is and it sends a system of application to your instrument. Konokal is one of the great jewels of India.

It’s important to understand that konokal is not only just a part of Indian music. If you know konokal you can understand African rhythms, Cuban rhythms, Jazz rhythms, because rhythm is rhythm in the end. Konokal is just a system to understand and apprehend rhythm. I encouraged Ranjit to use konokal in the 4th Dimension long before recording this album and he used these techniques on a number of our past compositions. On “Kiki” Ranjit sings konokal and Gary Husband, who plays both drums and keyboards brilliantly with us, answers on his drums exactly what Ranjit is singing. It’s really wonderful spontaneous playing.

GW: It’s testament to where the band is at now.

This chat would not be complete without honoring the centerpiece of Black Light, the beautiful acoustic piece “El Hombre Que Sabia” which you composed with the late and great Paco De Lucia. He passed along suddenly and sadly last year and I’m sure this loss is a difficult subject to approach.

Your guitar trio album, Friday Night in San Francisco featuring you, De Lucia, and Al Di Meola, is one of the most important live acoustic recordings of all time. How did playing with Paco De Lucia change you and your music?

JM: Dramatically. Before jazz caught me I played classical piano and picked up the guitar at age eleven. Soon after I was exposed to flamenco guitar playing and I instantly fell in love. I wanted to be a flamenco guitarist. I was living in the Northeast of England just south of Scotland where nobody even knew of flamenco. Without a teacher it’s pretty impossible to learn how to play properly. I was captured by jazz pretty short after that. I used to hitchhike down to Manchester after school just to see flamenco guitar players at age fifteen.

Then I heard Miles Ahead (1965), which was a recording of Miles Davis with the Gil Evans Orchestra, and there was a tune on there called “Blues for Pablo.” Miles revealed his profound love and affection for Hispanic music. He was without a doubt the godfather of fusion music. He was playing the blues as a jazz musician with a flamenco feel. I was blown away by this sound. Miles had become my hero by this time and to hear his affection for flamenco at this time was very endearing.

Fast-forward to 1978, I was in Paris in somebody’s car with the radio on and was enchanted by this recording. I didn’t know it was Paco [De Lucia] until the end of the piece and I thought, “I need to find this guy!” And I was very lucky that he happened to be in Paris. When we met I told him “I don’t just want to record with you, I want to work with you.” And then we worked together. At first we just jammed together and he thought it was great. We wanted three guitarists in this collaboration and we had different variations. Briefly we had with us Larry Coryell in 1980, which was short-lived and soon after Al Di Meola came to play with us. The Friday Night in San Francisco record sold over a million copies, which was just remarkable.

I would also like to mention that Paco and I did many Europe-only tours. There is one particular tour we did in the 1987 and one of the concerts we did was in Switzerland. It was a beautiful night. Two crazy guys, with a fantastic audience at the Montreux Jazz Festival, and finally after pestering them for all these years we’re releasing it. I just finished mastering the two track tapes, since there were no multi track tapes back then. What you hear is just the real performance. I am just thrilled that this performance is finally coming out early next year.

Back to the song we were supposed to record last year, when Paco passed I changed the name of the composition to “El Hombre Que Sabia,” which means “the man who knew,” because Paco really knew. What a musician! It was one of the tunes we planned to record as a duo and this particular tune he was very fond of. It’s another homage to Paco and I love the way it turned out with the 4th Dimension. It’s much lighter and I’m on acoustic guitar, Gary is on acoustic piano with light percussion accompaniment. It’s for Paco and I miss him dearly. We spoke right before he left for Central America, which was early February last year. On the 25th of February he died of a heart attack on the beach in Playa Del Carmen, Mexico. People like him live forever.

GW: It’s meaningful to have “El Hombre Que Sabia” as the centerpiece of Black Light. What a beautiful tribute.

So the music on this record is poignant and depth full. I could see it really evoking some energetic reactions from crowds when you do takes these tracks on tour with you. Have you noticed any change in how the crowd engages with your music over the years? How?

JM: I’m very fortunate since there really isn’t a record industry anymore I rely on performance to thrive and I feel that with the 4th Dimension things are very good. I’ve been around a long time don’t forget Dylan [laughs]. Musically I’ve never felt better in my life. Anytime someone like myself from the Biblical Age of the 1970s is still performing [laughs] music becomes the perfect vehicle for enjoying life and existence.

I would say my music has generally been on the higher energy side of things. Take the guitar Trio with Paco and Al even. There was some intense music going on there. Shakti also, which was an acoustic band for which I got a lot of flack from my agent and my record company. In their eyes, I had a really successful electric band and here I was sitting on a carpet with those Indians, playing acoustic guitar! My philosophy is that I need to remain true to myself and then I don’t betray anybody.

The thing is that over the years I really don’t see any difference in the audience’s reaction. Everything depends on the music. If the music is really strong in love, affection, passion, and joy, then the people feel it. We’re all built like that. Of course you might have a bad night. But the times where you do get it marvelous inspiration and you’re lost in the freedom of expression spontaneously. This is what we live for. Audiences all over the world recognize that. Music reminds all of us where we all belong. Music reminds us of home. We’re all made of the same thing. We’re all connected. Music on a really good night with the right people can show that. This is what we live for.

GW: Thank you so much for this beautiful chat John.

JM: My pleasure Dylan.

John McLaughlin and the 4th Dimension’s new album Black Light will be available via Abstract Logix on September 21st, 2015.