As Tim O’Brien and Friends kicked off the final set of RockyGrass 2012, I planted my feet a couple of yards behind the elevated stage. The canopy of treetops overhead, awash in color from the stage lights, absorbed a light drizzle. To my right, the deity of all double bassists, Edgar Meyer, calmly warmed up next to the main stage staircase. He would join O’Brien and fellow bassist Mike Bub momentarily. Aoife O’Donovan, the spritely young phenom who floored the crowd all weekend long with her diaphanous vocal harmonies, fluttered and spun in tight circles off in the wings of stage left. A wave of inspiration hit me. I opened my notebook and began writing: “Despite Casey Driessen’s lightning quick fiddle fills and the thunderous pops and thwaps emerging from Mike Bub’s upright bass, an aura of peace and tranquility surfeits the air, engaging all nature, human and…”. But before I could finish writing that mawkish drivel, a stout, Buddha-bellied bearded man, clutching a can of beer in his hand, approached me.

“Journalist?” he snarled.

“Kinda, sorta,” I replied, unsure of what he wanted.

The man took a swig and continued, “Well, write this down. I asked Craig (Ferguson, RockyGrass festival director) if I could teach a full week unicycle class next year and he turned me down!”

By now, I sensed the jest in his voice and played along.

“During RockyGrass Academy? You wanna teach unicycle lessons?” I asked.

“Yep! But he said no. I just thought you should be aware of that for your article.”

A bit incredulous, but still not understanding the joke, I said, “Okay, but I need to know your name if I’m going to use this.”

The man stuck out his right paw and, in a husky voice, he said, “Vince. Vince Herman.”

A Series of Confluences

Planet Bluegrass Ranch is a beautiful riparian venue, cradled to the north and east by the North St. Vrain Creek and buttressed by the mantle of Lyons’s majestic sandstone cliffs. Less than a mile away, the St. Vrain River is forged from the confluence of the North and South St. Vrain Creeks. But it was back at Planet Bluegrass Ranch where a host of more poetic confluences – musical, communal, historical, and generational – materialized along the banks of this teeming creek. Even Planet Bluegrass’s logo, displayed from the apex of center stage, is a confluence. It’s an adaptation of the Yin-Yang called the “Yinjo Yangdolin”.

I have been listening to Leftover Salmon for at least a decade and also attended a handful of their shows. So how is it that I failed to recognize their guitarist, Vince Herman, who is also one of Colorado’s most famous and beloved musicians?

Beginning with RockyGrass Academy, which commences five days prior to the festival, the musicians become part of the landscape, not a cut above it. They arrive to teach amateur bluegrass enthusiasts, participate in midnight picking sessions on the campgrounds, and, from all observations, revel in the artistry of their peers joining them on the three-day bill. Throughout the weekend, I saw men that are associated with virtuosity – Sam Bush, Noam Pikelny, Ronnie McCoury, and Jesse McReynolds, to name a few – conversing with fans and displaying a high level of ebullience while listening to their fellow pickers perform. I was reminded that they are not only star musicians, but fundamentally, huge fans just like everyone else. Or, in Planet Bluegrass parlance, “Festivarians”.

On Friday evening, for example, while The Punch Brothers were forging a masterful set, their peers could be found clustered in the crowd, braving the rain with everyone else. Yonder Mountain String Band’s Jeff Austin sat in the fourth row and sang Ophelia to his young daughter while Thile paid homage to the late Levon Helm on stage; Casey Driessen, in lieu of a chair, squatted a row back, behind Austin’s wife; living legend Tim O’Brien sat in front of the Austins, with one arm around his wife; and guitarist Michael Daves was seated a few chairs to their right. And those were just the musicians within my sightline. While some bands had obligations that limited their stay, RockyGrass is not the type of festival where the tour bus shows up, the set is executed, and the band departs with alacrity. No, RockyGrass is a celebration where bluegrass artists – first, second, and third generation – bring their families and make a weekend, and in some cases, an entire week, of the occasion.

So as the festival was coming to a close, why is it that I didn’t recognize Vince Herman, a famous guitarist I’ve seen dozens of times either in person or photographs? The integration of professional musicians into the larger RockyGrass community – the confluence of their roles not merely as entertainers, but also teachers, family men, and adoring fans – was the likely culprit for that hiccup in simple facial recognition. Vince was one of at least 30 people who approached me, unsolicited, over the weekend. Musicians and fans alike, who might ordinarily be wary of journalists, were dying to gush about RockyGrass – or talk about unicycles – on the record.

“Bigger Tarp, More Friends”

At 9:30 a.m. on Friday, I entered the Planet Bluegrass Ranch festival grounds to a sea of tarps, stretching at least 50 yards from the stage and extending 60 yards across the breadth of the field. Most of the lawn was covered with a patchwork of large rectangles: blue, brown, burnt orange, pine green, some crusted with old dirt, others emitting the scent of brand new, sunbaked plastic. While there are many facets of RockyGrass that fans look forward to, the tarp run has to be high on the list. People line up at midnight to receive a lottery number. Once everyone has a card, a number is drawn at random to determine the order of the queue and, nine hours hence, entry when the gates open. Festivarians dash to acquire premium real estate close to the stage, laying down tarps for demarcation. But why the rush? Brian Eyster, communications and marketing director for Planet Bluegrass (and Festivarian since 2000) explained:

“We’re committed to the single stage idea. Most festivals aren’t. It comes back to the idea of community. People run in and claim their spot at the beginning and they have a shared experience throughout the day. Everybody’s in one place and everybody’s hearing the same music. It fosters community because everyone is sharing in the same experience (and not traveling from one stage to the next).”

If the tarp run sounds hardcore, it very well may be. But it does not contravene the tenets of community, sharing, and egalitarianism that are heavily promoted in Planet Bluegrass events. Before 23 String Band christened the festival Friday morning, a RockyGrass representative took the stage to announce the official tarp policy. Any individual could move up and sit on someone else’s tarp if all, or even just a few, of the occupants were walking around the grounds. Unofficially, people who had larger tarps than necessary would often encourage fellow Festivarians, especially those of whom they’ve never met, to sit with them. I saw a threesome of women walking around in ‘70s style three-quarter sleeves tees with the words “Bigger Tarp, More Friends” emblazoned across the chest. Friendships can be almost instantaneous.

No more than an hour later, I decided to take advantage of this policy. And that’s when two things happened; first, I met Bill, Joy, and Greg, and, a little while thereafter, I decided that a review focusing solely on the music of the festival would sell the true greatness of RockyGrass short.

Traditional Bluegrass or Big Tent?

While Telluride is unequivocally the more well-known of Colorado’s two main bluegrass festivals, RockyGrass is actually one year older. The father of bluegrass, Bill Monroe, started the Rocky Mountain Blue Grass festival in 1973. He booked the talent while the fledgling Colorado Bluegrass Music Society organized and promoted the event. The Adams County Fairgrounds played host (relocation to Lyons didn’t occur until 1992) to some of the biggest luminaries of the scene. Ralph Stanley’s RockyGrass debut came at the second annual event in 1974; Jesse McReynolds, along with his now deceased brother Jim, was initiated a year later, in 1975; and Tim O’Brien, who played his 29th RockyGrass this year, made a name for himself in the fiddle and guitar competition in 1975, as well. It was no mere coincidence that all three legends were on the bill for the 40th anniversary celebration. Eyster asserted: “The lineup has been crafted to reflect the earlier years of the festival with seminal artists (like Stanley and McReynolds)”.

But it does not lean solely on the big names or styles of bluegrass royalty. Eyster explained, “We wanted to fill out the lineup with young acts that are on the rise like Trampled by Turtles and The Punch Brothers. The best RockyGrass festivals balance gritty traditional bluegrass with progressive elements and even some surprises.”

While Eyster’s assessment of balance, in my opinion, is absolutely correct, there has been a fierce debate, one that has spread all the way to the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA), about what constitutes real bluegrass. Traditionalists, or “purists”, point to the arrangements of first generation artists like Monroe, Stanley, McReynolds, and Earl Scruggs as truly consonant with the genuine article. They dismiss the newer eras of phenoms – such as Crooked Still, The Infamous Stringdusters, and Yonder Mountain String Band – who have introduced elements of rock, jazz-fusion, extended jamming, and, in some instances, unique instrumentation such as the cello. Newgrass, or “progressive”, fans prefer a big tent approach – while they may favor one style over others, all are welcome. The only immediate concerns of full inclusion are market share and visibility. Progressive artists tend to rake in a heavier portion of both. Amateur banjoist and singer Nina Dropcho, who also writes a bluegrass column, described this position: “So long as progressive bluegrass doesn’t kill off traditional bluegrass, then we’re fine. As long as we have both, there’s room for everybody.”

All genres and generations of American music have paid tribute to their foundations, but none has remained prohibitively enslaved to the sound of its founding fathers. Charlie Parker’s bebop, Miles Davis’s modal jazz, and Herbie Hancock’s funk-fusion all displayed an awareness of, while completely embellishing upon, the aesthetics developed by Louis Armstrong. Likewise, Stevie Ray Vaughan and B.B. King could borrow Lead Belly’s chord progressions while concomitantly sculpting the blues to their own sense of euphony and showmanship. In much the same manner, a farrago of second and third generation innovators has ensured that bluegrass continues to expand and thrive upon the foundations created in the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s. While RockyGrass has a reputation of focusing on more traditional bluegrass, there was a healthy dose of progressive music that expounded upon Bill Monroe’s arrangements.

Trampled by Turtles, who played the early evening set on Friday, was a salient part of this mix. None of the 20+ acts on the lineup card approximated the speed and ferocity with which TxT blazed throughout its uptempo pieces. “We really beat up our instruments,” acknowledged mandolinist Erik Berry. Like his bandmates, Berry’s style and flare are heavily influenced by rock ‘n’ roll. Growing up, he emulated Eddie Van Halen, Jimi Hendrix, and all of Ozzie Osbourne’s guitarists, “even the lesser known ones.” He then went on to recite the exact chronology of Ozzie’s axe men, even digressing into a soliloquy on Jake E. Lee.

On multiple occasions, TxT brought a throng of jamband fans to their feet with rock-oriented sequences of accelerando and, in some cases, metal-influenced thrashing and headbanging. But this was not a one-dimensional band pulling from a single aesthetic influence. More than just extracting an electric sound from acoustic instruments, TxT channeled one of Berry’s heroes, Ralph Stanley, during beautiful ballads interspersed throughout the set. The unique confluence of styles, tempos, and techniques was exquisite.

And while it may provide a bone of contention for purists, Berry appears unsympathetic to their concern. Of everyone with whom I spoke, he delivered the most incisive anecdote on the fait accompli that is genre evolution: “We’re walking through the airport earlier and someone asks us, ‘Are you a bluegrass band?’ To a bluegrass purist, we’re supposed to say ‘no’. But we’re in an airport, so what am I supposed to say? ‘We’re a rock-influenced string band?’ In 20 years, natural selection will get rid of a lot of people with an ‘anti’ opinion….Do people expect Buddy Holly, CCR, and Radiohead to sound alike? They’re all rock!”

Sam Bush – Connecting Purists with Progressives

In furtherance of Berry’s point, progressive sounds, styles, and techniques often convolve into the mainstream musical etymology. A lexicon – language or music – lives, breathes, and grows forever larger. Sam Bush, who headlined Friday, chartered New Grass Revival in 1971, just two years before RockyGrass came into being. The band was on the vanguard of the progressive movement, employing traditional instruments to play rock, blues, and jazz-influenced bluegrass. Even their raiment and shocks of long hair were a source tension with purists at the time. When I sat down with Bush, he found more than a hint of irony in retrospect: “When I played in New Grass, we turned heads, but then evolution occurred and it was basically normalized. What we played in New Grass was considered progressive, even edgy, but it definitely sounds like bluegrass today.” However, Bush revealed that the strong sense of brotherhood he forged with his New Grass bandmates, as well as the likes of Edgar Meyer and Jerry Douglas (Strength in Numbers), was anchored not so much in their unique sound, but their shared roots: “As progressive as we’ve written certain tunes, bluegrass is our common denominator and that’s where we tend to meet up, so to speak.” Instead of conspiring to alter traditional bluegrass, the confluence of styles brought to bear in Bush’s bands has, instead, expanded upon its pulchritude and appeal.

Bush is second-generation bluegrass royalty. Just as the name of Monroe’s band, The Blue Grass Boys, birthed the genre’s original appellation, Bush’s 1971 collective introduced the moniker that would come to define the progressive subgenre of his contemporaries (Seldom Scene, New South): newgrass. And if Bill Monroe’s bluegrass is the sun and newgrass is Mercury, then third generation progressive grass (Yonder Mountain String Band, The Infamous Stringdusters, Crooked Still, et al.) would be Venus, orbiting on a different axis a little further away, but still wholly dependent on the central star in the solar system.

If there is one satellite in the whole of bluegrass that has been everywhere in the galaxy, it is Bush. He has shared the stage with just about every picker who has ascended to stardom. From first generation pioneers like Monroe and Scruggs; to his contemporaries like promethean flat-picker Tony Rice and dobro extraordinaire Douglas; and finally to the prodigious, free-wheeling, genre-bending trailblazers of today like Mike Marshall and Chris Thile, Bush has picked with them all. So it was fitting that, on Friday evening, he paid homage to his roots while, at the same time, passing the torch.

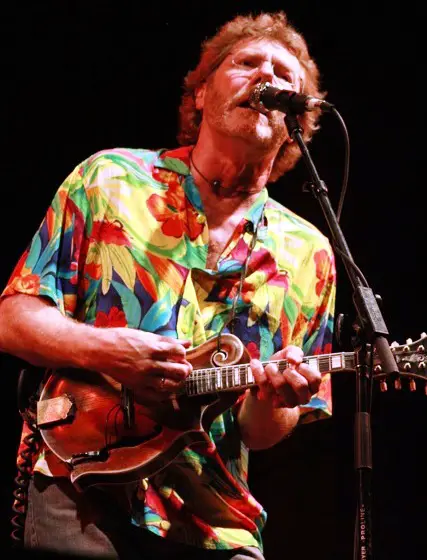

Bush, along with Scott Vestal (banjo), Stephen Mougin (guitar), Todd Parks (bass), and Chris Brown (snare drum), serenaded Festivarians with over two hours of traditional bluegrass. Well – compared to his sonic explorations of the ‘70s and ‘80s, relatively traditional bluegrass. Classics like The Osborne Brothers’ Big Spike Hammer, were interspersed with newgrass favorites such as John Hartford’s Steam Powered Aero Plane. All the while, Bush demonstrated why, at 60, he is still one of the most well-regarded mandolinists in the world. Given the nature of the set, his famous full-forearm tremolo was not as salient as usual, but his neckwork was, as always, scintillating.

“After I listen to Sam, I want to burn my mandolin,” Billy Wilson confessed, with total affection. “Sam is the greatest of all time.” An amateur picker, Wilson first attended RockyGrass in the early ‘80s, but like many Festivarians, lost track of how many he has seen. For decades, the community consensus aptly reflected Wilson’s GOAT assertion. But in recent years, mandolin prodigy Thile, of Nickel Creek and, more recently, Punch Brothers, fame, has dissolved this unanimity. Interestingly enough, Bush has been one of the most vocal advocates of Thile’s ascendance. Before his band took the stage, he invited Thile, 31, out to lay down the harmony on Brilliancy. A current surged through the crowd in awareness of what was happening – the two most gifted musicians in their particular instrument, creating electricity on stage. During our sit down before the show, Bush explained why he chose Brilliancy for the duet.

“One time Chris said to me, ‘Hey, would you play Brilliancy? I think I know the harmony.’ And he did. For me, Brilliancy is pretty challenging, but I say this about Chris Thile and Mike Marshall – anything I can play, they can play the harmony to it. I admire Chris’s musicianship so much because really whatever instrument he chose, he’d be probably the best you ever heard on it. Mandolin is his instrument of choice and I’m really happy about that.”

For the record, Thile’s guest spot marked his fourth appearance, out of nine total bands, for the day. In each incarnation, he augmented the sound with his lightning quick fingers, soulful vocals, and dynamic stage presence reminiscent more of a vaudeville star than a musical prodigy.

After a sublime mandolin duet, Bush bid adieu to Thile and brought his band out. In addition to songs from the bluegrass canon, they peppered the set with diverse covers that, lyrically, promoted a unifying theme. In a nearly 10-minute rendition of Bob Marley’s One Love, Bush incited the crowd to sing the refrain – “One Love / One Heart / Let’s get together and feel all right” – a cappella near the end. He dedicated the next song, Joni Mitchell’s One Tin Soldier, to the victims of the recent Aurora theater shootings. Her poetic message advanced upon Marley’s simple proclamation:

“And they killed the mountain people, so they won their just reward / Now they stood beside the treasure, on the mountain dark and red / Turned the stone and looked beneath it / Peace on earth was all it said.”

While the origins of Bush’s covers spanned from bluegrass to reggae to folk, he incorporated the same views that Planet Bluegrass actively promotes – community, benevolence, and inclusivity.

Community, Benevolence, and Inclusivity – Words Transform Into Action

On Friday, less than an hour after my arrival, I decided to take advantage of RockyGrass’s generous tarp policy. I left a cooler, extra clothes, and Crazy Creek on my tarp and winded my way to the front of the field. I spotted a vacant blue patch in the second row and, after sitting down, struck up a conversation with a trio of friendly faces. My neighbors, Bill Hogrewe, Joy Barrett, and Greg Mudd, baby boomers all, were each closing in on their 20th RockyGrass. Like almost everyone else I met who was initiated last century, none of the three could remember his or her exact baptismal year.

Greg works at Bart’s Music Shack in Boulder and is also a freelance photographer. He sported a woolly charcoal beard and may have been the only person at RockyGrass with actual film in his camera. I immediately took to him. Greg was eager to watch first generation lions Jesse McReynolds and Bobby Osborne perform, but like most Festivarians with whom I spoke, revels in the discovery of new talent building on their roots: “Leftover Salmon, String Cheese, and Yonder Mountain were very much influenced by Bill Monroe, Peter Rowan, and other (traditional) musicians,” he contended. Cognizant of the success engendered by these three Colorado bands, Greg recoils at the thought of even younger generations hamstrung by a restrictive set of guidelines. Half the fun is listening to novel, ground-breaking musicians take their predecessors’ sound in uncharted directions. Even if that direction is back toward Big Mon. After Thile and Daves delivered a musically and theatrically stunning performance, Greg exclaimed, “The set with Chris and Michael was mind-blowing! If they ever decide to get a great bass player like Sam Grisman, as well as a fiddle and banjo player, that could be the next big thing for traditional bluegrass.”

Greg’s friends, Bill and Joy, are married and live in Boulder. They started coming to RockyGrass soon after its 1992 relocation to Lyons. The couple moved to the East Coast, twice, but returned to Lyons almost every year for this late July celebration. Bill donned a thick mane of silver hair and cropped beard of matching hue. His face and demeanor were both sanguine throughout the weekend. And Joy had the kindest eyes and an even gentler spirit. The couple recalled some of their fondest memories of RockyGrass, even those that occurred more than a decade ago, with robust detail. But for all their vivid retellings and quotable reminiscences, it was the actions Bill, Joy, and Greg took that made the largest impression.

When the owners of the vacant blue tarp returned Friday morning, my temporary neighbors immediately extended their hand of friendship. They invited me to hang out with them any time I wished on their tarp. They worked hard to claim real estate in the first or second row (center stage) all three days, but made a habit of including me in their circle. Despite my peripatetic habits, I knew I could always return to watch the action from a premium vantage point.

During the second afternoon, all of that walking caught up with me. That, as well as a 13-hour sunbaked Friday and six hours of 90-degree heat on Saturday. My eyelids became heavy. After The Hillbenders' mid-afternoon set, I decided to take a nap on my tarp and recharge for the evening. An hour or so later, when I awoke, my backpack – along with the camera, iPad, glasses, sandals, notebooks, and keys inside it – were nowhere to be found. For three hours, without even a pair of shoes to assist, I searched the grounds to no avail. All the while, everyone around – Bill, Joy, Greg, random people who saw me scouring the field, the ticketing station employees who also ran the Lost and Found, and even the backstage security guard – assured me with an unusual amount of conviction that my bag would be found. “People at RockyGrass would not steal your bag,” was the universal affirmation I got over and over from veterans of the festival. I wanted to believe that but I also knew that it would only take one bad apple.

After resigning my search, the backstage security guard offered to walk to his tent (on the adjacent campgrounds) in between sets to loan me his sandals. An hour later, when I was squinting to see Béla Fleck’s nimble banjo rolls, a girl to my right offered me her glasses to see if they worked. Lo and behold, we had the same prescription. Just like binoculars at a sporting event, she passed me her glasses intermittently so I could catch glimpses of Béla, Ronnie McCoury, Alan Bartram, Danny Paisley and Jason Carter. Similar to the set Bush put together, his former New Grass bandmate paid homage to the forebears of bluegrass with 90 minutes of traditional arrangements.

Throughout the evening, and into the next day, Greg implored everyone who would listen to be on the lookout for a gray backpack with green trimming. Bill and Joy chimed in as well. When Béla closed out his set around 10:30 p.m., and I still could not locate my car keys (among many things), they did not hesitate to offer me a ride home. My feet were shredded by night’s end and, despite politely declining the security guard’s altruistic gesture, I gladly accepted a spare pair of Bill’s sandals to avoid further damage.

While my backpack was still nowhere to be found, I decided to hold out hope. After all, if total strangers were offering me their clothes, glasses, a ride home, and helping me search for my bag, then maybe it was true – maybe it really wasn’t possible to have my valuables boosted in such a kind and benevolent community.

At the Junction of Multiple Generations

The most striking feature throughout the 40th anniversary RockyGrass was the seamless confluence of generational participation and enthusiasm. This makeshift community would be unable to flourish, or even sustain itself, without membership from all age groups. From toddlers to teenagers, swaths of children could be found taking guitar lessons at RockyGrass Academy, wading in the creek, and listening to the sultry sounds of banjo rolls and bass licks with their families. Similarly, yet conversely, one could spot septuagenarians dancing together, cheek-to-cheek, in the muddy aisle behind the soundboard.

But even more remarkable was the ubiquitous sense of trans-generational egalitarianism – a cooperative spirit that razed the walls and barriers people frequently (and often without noticing) erect in everyday life. Bill, Joy, and Greg all had a good 20 years on me, but their invitation smacked of one second grader telling another whom she just met, “Come over to my house after school to play!” And they were not alone. Across the sea of tarps, The Greatest Generation, Baby Boomers, Gen-Xers, and beyond broke bread together and shared in the mirthful music that transcends epochs and eras.

This transcendence could also be found on stage. Famed banjoist Ben Eldridge hammed it up on Lay Down Sally during Seldom Scene’s Sunday spot; while on Friday, his son, guitarist Chris, gilded Punch Brothers with his golden guitar picking. Pickers like Sam Grisman and brothers Rob and Ronnie McCoury proudly carried the torch in their famous fathers’ (David and Del) absence this year.

And the good majority of artists talented enough to get an invite to RockyGrass paid tribute to an older generation of masters who can never play RockyGrass again. Scruggs and revolutionary flat-picker Doc Watson, born 10 months apart in the Roaring ‘20s, both died this year and were eulogized by one musician after the next on stage. Tim O’Brien, 58, made a special point to commemorate these two lions during his set. Former Hot Rize bandmate Pete Wernick, 66, joined him for most of the evening. Wernick announced that when North Carolinians Watson and Scruggs came to play near his home in New York City, “it was like gods in our midst.” Additionally, The McCoury brothers made a guest appearance with O’Brien to pay tribute to Scruggs.

Almost, but not completely, lost in the mix of honoring Watson and Scruggs, as well as Levon Helm (who also died this year) and Everett Lilly, were O’Brien’s own sublime creations. Nellie Kane nodded to the traditional happy-grass of the ‘50s and the pulsing accelerando of Land’s End sent a thrilling shockwave through the crowd.

The mural of trans-generational cooperation was brought to fruition by artists who, representing a medley of bluegrass epochs, collaborated together on stage. O’Donovan, 29, the young vocal stylist with an ethereal mien, harmonized with O’Brien and guitarist Peter Rowan, 70, during Helm’s sendoff on The Weight. “She uses her breath to let the song float on the wind,” Dropcho stated. There was, in fact, a buoyance in the piece. Helm would have been taken aback at the polyphony engendered by O’Donovan, Rowan, and O’Brien during the refrain.

But this confluence of generations was at its most profound during a Saturday afternoon session housed in the densely packed Wildflower Pavilion. The roofed, but outdoor, venue resides in between the larger campground and the back edge of the main lawn. While it fields a limited number of RockyGrass sets, it hosted maybe the most memorable event of the entire weekend. Three masters – Jesse McReynolds (83), Béla Fleck (54), and Ronnie McCoury (45) – who blossomed in three different eras treated the standing room only crowd to one of the most sybaritic experiences a bluegrass fan can enjoy. At his advanced age, mandolin powerhouse McReynolds was sharp as a whip in both his picking and humor. He incited laughter and awe in the crowd with stories about his wife and working on a tribute to Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter. McCoury, meanwhile, played the sidekick during his stories – the Ed McMahon to his Johnny Carson. Words cannot begin to do justice to the sublimity of those mandolins, plus Béla’s banjo, combining to knock out Nervous Breakdown. The dexterity, speed, meticulousness, and tone with which it was played, while all three men raced in perfect synchronization, led me to actually pinch myself – I thought it was too good to be real. But I wasn’t dreaming. The applause that followed was deafening.

The only other event approximating that level of precision and power was another feat of trans-generational collaboration; Thile joined his former teacher, John Moore, as well as mandolin virtuoso John Reischman, during Bluegrass Etc.’s early afternoon set on Friday. Girded by the rhythm of Moore’s bandmates, Dennis Caplinger and Bill Bryson, the triptych of mandolins created scintillating textures and harmonies on classics like Salt Creek and White Freightliner.

Coda

With my car still locked in a dirt field at Bohn Park, I had no way of getting back to Lyons for the third and final day of RockyGrass. When I awoke Sunday morning, I was resigned to missing the festivities. Yet somehow, as Peter Rowan and The Travelin’ McCourys hit the stage, I found myself standing in the second row of Planet Bluegrass. A gray bag – replete with camera, iPad, glasses, notebooks, and keys – was strapped across my shoulders and Joy’s arms were strapped across my back and neck. As a testament to the strength of this community, I swear that Joy was as happy, if not happier, than I was. We embraced for almost half a minute and I was overrun with emotions.

I was thrilled to be reunited with the contents of my backpack, but the wave of exaltation that overcame me had little to do with car keys or camera lenses. About 90 minutes prior to our mammoth hug, my phone rang: “We found it! We found it!” Joy shouted. Through a confluence of perseverance and altruism on multiple fronts, my bag was located. And thanks to a ride I hitched from Boulder to Lyons with my roommate’s friend, I was reunited with what truly mattered - my new friends. The same backstage security guard, the one who so kindly offered me his sandals the night before, spotted my bag in the early afternoon. He brought it up to the ticket office which housed the Lost and Found. The employees, also aware of the situation, alerted Joy, Bill, and Greg who, in turn, called me with the great news.

So on Sunday evening, with my backpack safely in tow, I stood on a slate of rock a couple of yards behind the stage. Meyer was practicing his bowing. With her eyes closed, O’Donovan swirled and swayed to the romantic descants of Casey Driessen’s fiddle. At that moment, I was reminded of something that Sam Bush told me two days earlier. While gushing about his hero, Bush stated: “I’ve been very fortunate because Doc Watson has influenced me in a lot of ways and some of them weren’t even musical. It was just the kind of person he was and the way he lived and how he treated people.”

Bush, who is famously one of the most beneficent spirits in all of bluegrass, intimated that his exemplar blazed more than just a musical trail. Watson’s personal prerogatives, the manner in which he treated people, played a significant role in shaping Bush’s own generosity. When I first sat down with him, he realized that the room we were in was a little noisy and might interfere with the sound of the interview recording. So he took me back to a small, quiet room where we both sat on a bed and he talked. I asked for seven minutes of his time and Bush gave me 15, not to mention a wealth of useful information.

This ethic of kindness, altruism, and community permeated the whole of RockyGrass. From Bush and the other musicians who spent time talking with me to Bill, Joy, and Greg; from the employees who helped me locate my bag to the random Festivarians who joined in the search. I could see this ethic through the environmental efforts to compost and recycle just about everything sold or used on the grounds. I could see this ethic in the tarp policies that encourage inclusivity and instantaneous friendship. I could see this ethic in a confluence of generations on the stage harmonizing to create sonic lullabies and fantasias. And finally, I could see it in the confluence of generations bonding with one another on the field, in the campgrounds, and, next year when I arrive at midnight, in line for the tarp run.

Above and beyond all the honorees alluded to in Tim O’Brien’s closing set, one more must be mentioned: Woody Guthrie. Two weeks prior, Guthrie would have turned 100 years old. In memory, and in perfect concord with the principles of community, benevolence, and inclusivity, O’Brien chose to sing some of the verses from This Land Is Your Land not ordinarily taught to grade school students. One of them hews closely to the RockyGrass experience:

“As I went walking I saw a sign there,

And on the sign it said ‘No Trespassing’.

But on the other side, it didn’t say nothing.

That side was made for you and me.”

At every other festival I have attended, the barriers that are created and observed between and among musicians, fans, security, journalists, and vendors are well established. There are figurative and literal “No Trespassing” signs all over the place. But at the 40th annual RockyGrass, those barriers were leveled by the kindness and enthusiasm of all in attendance. Everyone – paid employees, unpaid volunteers, and paying customers – worked to promote an idyllic atmosphere. A confluence of disparate people and personalities, anchored by their love of bluegrass, made it easy for me to understand why RockyGrass sold out in February and, above all, why thousands of Festivarians travel annually to Lyons for this pilgrimage.