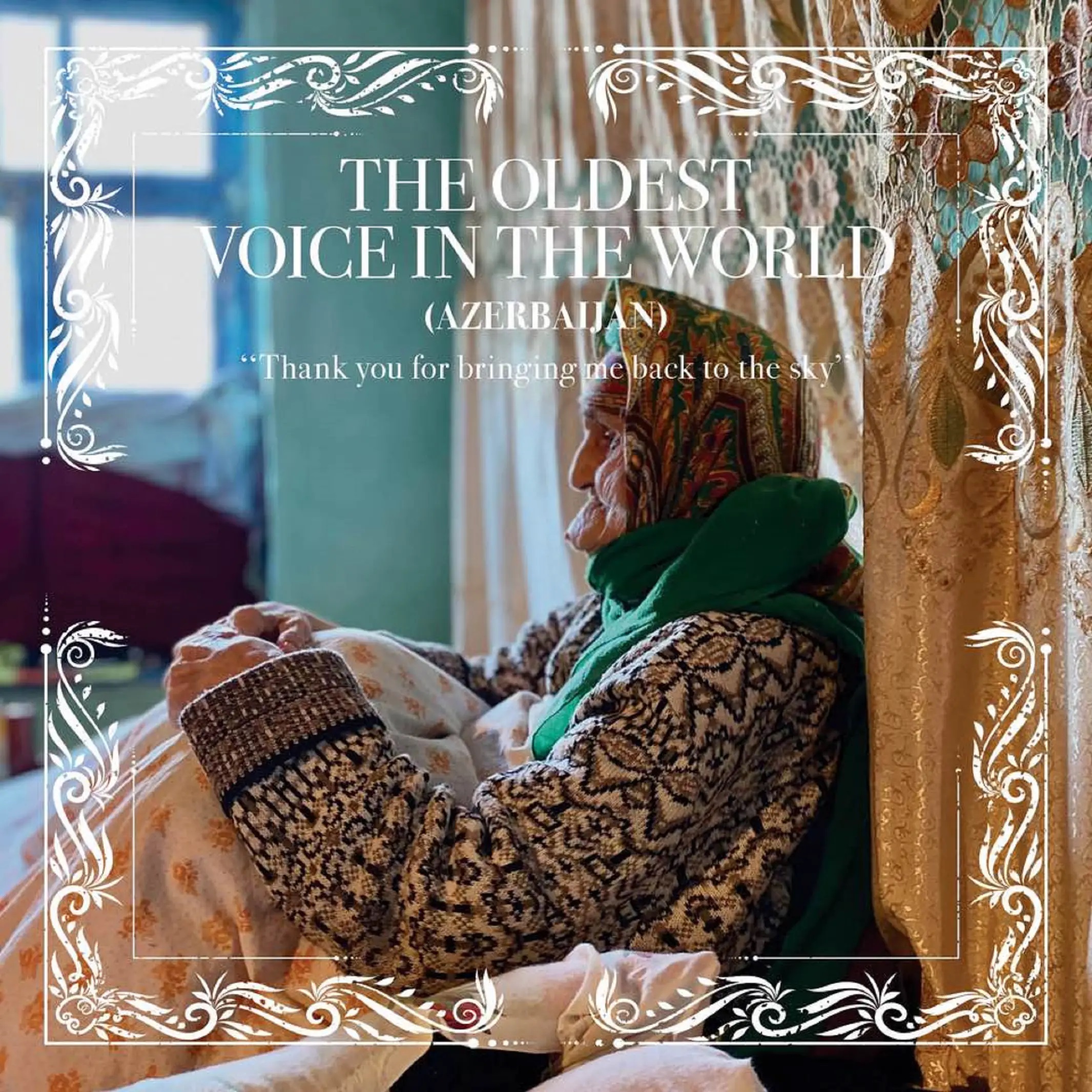

Single Sonic Seven is the self-titled debut album of a collective of musicians on all seven continents. Two years in the making, it is alive with soul, punchy beats, catchy hooks, penguins, and a turbulent backstory. Its roots are found in quarantine-era Berlin, while its final path was deeply shaped by a personal connection to the war in Ukraine.

Supported by a grant from the City of Berlin, electro producer Ethan Miska launched the initiative with a handful of friends from Berlin’s community of international musicians in the fall of 2020. “It was a Corona baby,” says Miska. “We wanted the album to be a reminder that we’re all in this together, and given the polarized state of the world today, we think that message is still relevant.”

Over the following two years, a remote global team evolved to plan, compose, and produce Single Sonic Seven, united by a belief in music’s power to transcend borders. Its main contributors are Usama Siddiq, Clementine Esquivel, Ikiedemhe David, Espin Bowder, Andrea Dixon, Ivan Imkhong, Nick Martyn, and Daneik Ashley, who collaborated from locations ranging from Ibadan, Nigeria to the South Pole.

The project’s path has been anything but smooth. While working remotely with the featured artists and other core team members, Miska produced much of the album while living in Kharkiv, Ukraine. On the eve of Russia’s invasion in February 2022, he abruptly relocated to his former residence of Berlin amidst dire warnings from family and friends. “To say the least, when the war broke out it kind of threw off my ability to nudge along the project for a bit,” recalls Miska. “A lot of us were battling with how seemingly insignificant and irrelevant it felt to be working on a creative endeavor.”

Feeling mostly unable to tangibly help out, Miska and the team decided to dedicate the album to Anna (name edited for safety reasons), a close Ukrainian friend who had become trapped in Russian-occupied Donbas. “It was a pretty chaotic time in my life and for S.S.S., so dedicating the music to someone really important to me, and who was incredibly supportive of this album, was the only thing that made our finishing it immediately relevant,” Miska notes. Throughout the spring of 2022, the Single Sonic Seven crew composed feverishly, ultimately finishing the music in May, within days of Anna’s escape after three harrowing months of occupation.

Single Sonic Seven, spanning seven continents and genres ranging from pop to experimental, Went live on Friday, January 13th 2023 on all streaming platforms. All revenue from streaming and album sales will be donated to Helping To Leave (helpingtoleave.org/en), an organization which has aided thousands of Ukrainian civilians— including Anna— in fleeing areas of active conflict.

Closing the conversation with Ethan, I asked him to grab the closest book he could find. Holding The Adventures of Tintin, a famous comic series created by Georges Remi, Ethan explains, “Before I could even read, I would look at these pictures and follow along. I like a good adventure, and it's always some kind of adventure with these Tintin novels. It’s the same emotion that I go after when I'm making the music that I make; I want to create something that makes my heart pound.”

Read on below to learn more about Ethan Miska and his mission to make heart pounding music with a whole lot of heart.

GW: So tell me about you and this project.

EM: For the last million years (it feels like) it has been all about Single Sonic Seven. The elevator pitch for it is that it's an album I composed with various other musicians, including a featured musician on each of the seven continents. That is the connective tissue of this project. Single Sonic Seven is something that has been following me around for the last two plus years, and at some points it has felt like the coolest thing in the world, and at some points it has felt like this big, heavy sack that I've been dragging around with me wherever I go— mostly during the period when I'm not working on it as much. When I am in the thick of it, it's really nourishing. As for the first part of your question about me— I'm the guy with Single Sonic Seven (laughs). It has been my identity lately. Maybe a bit more than I would like it to be. I grew up in the San Francisco Bay area, but for the last five years I was living in Europe, mostly in Berlin, Germany, which is where the project, Single Sonic Seven came about. It was during the quarantine in 2020, and I wanted to do something radically more collaborative than I had done before, within the confines of being in my room and not going to too many places. So, that is me. I make beats. I collaborate with different kinds of musicians. And I am re-adjusting to life in the United States, and to being back in a place where I’m not exotic for being from California, which is probably good, since it's silly how far that can go in some places.

GW: I know what you mean. It’s also easy to be considered “exotic” when you are a transplant living in the middle of rural Nebraska (laughs).

EM: I often feel that cities are overrated. I love cities, but I feel like in the 21st century, with the availability of means of collaborating and just engaging with other people beyond the immediate physical realm, I just don’t feel like we all need to live in Berlin, L. A., New York or Paris in order to do a lot of the things we're trying to do. At least as far as creative collaboration goes. So more power to you for being in Nebraska, because I feel like it's evidence of that. And also it's what I’m telling myself right now since I am living in the town that I grew up in, and there are around 60,000 people. It's not a musical mecca, but I feel like I'm plugging away just as much as I was able to when I was living in places that are better known for having a music scene. As far as collaborating, I do feel like the in-person thing is important in some aspects, but otherwise, everybody's just everywhere. I feel like there's a crucial ten percent, where it’s really helpful and refreshing to develop the “boots on the ground,” but the other ninety percent, it's like, “well here I am on my computer again.” And yeah, at least for me, I don't feel severely restricted.

GW: So how does the collaborative process work? I mean, how do you even connect with artists in Antarctica?

EM: There has been absolutely no formula or consistency with anything in this project (laughs). We have tried so many different systems and approaches. It has all been this big collage. I’ll use this as an opportunity to answer your question about Antarctica— that was actually, in some ways, the easiest continent to find people to collaborate with. There was no second guessing who we were going to work with, because it's like, “you're a musician in Antarctica? We would love to work with you!” And we ended up working with a really cool musician who works at the South Pole station playing glockenspiel, which is something that was just completely outside of my creative palate. So we had the honor of collaborating with the southernmost glockenspiel player in the world. How often does that kind of thing come about? Some of the collaborations, including that one, were just sending emails back and forth, and not even a whole lot of emails. I do actually like zoom calls to figure out how to structure a song, or which hook to use, or whatever, but in some cases it was just like, “okay, here's a couple recordings. Have fun. Let me know if I can help with anything else.” And we just took it and ran with it.

GW: How did you know who to contact?

EM: We just reached out to anyone we could think of who has any sort of connection to Antarctica. And, by the way, the “we” that I keep referencing is me plus a handful of core people who have been involved with the project in some way or another for the last couple of years, sort of like the organizing team. So it was basically an elaborate strategy of emailing people we knew who might have some kind of connection to Antarctica. And through that we got in touch with Andrea Dixon, our collaborator down there. It was actually a similar process for some of the other collaborations, but it was also a real mix. In some cases we had an idea of like, “oh, we're familiar with this person's music, we checked it out, it sounds great, and I think it would work really well with this existing song.” And then in other cases, it was collaborating with existing friends, or friends of friends.

GW: Anything else outside your creative palate that you were introduced to? Any other new instruments?

EM: New instruments. I will add that if people hear “seven continent album,” and they're expecting to hear bongos in the Africa collaboration, or didgeridoos in the Australian collaboration, or pan flutes in the South American collaboration, they're probably going to be really disappointed. It doesn't sound like that. It is electro--- and that is such a nebulous term for a genre, but it goes all over the place. There's some stuff that's a bit more— I don't know, not quite avant-garde, but it's not sound art, and it's not “world music,” whatever that means. There's a narrative connecting thread, in addition to the musical connecting thread, so as far as music instruments that I got exposed to, the glockenspiel is pretty much it. We were using guitars and samples from vocalists. Penguins did make their way in the Antarctic song, but as far as the other sounds go, we worked with conventional types of sounds that one would expect to hear in contemporary electronic, or alternative electronic music. Just had to throw that in there.

GW: I love that you threw that in there. I didn’t even realize that I had this preconceived notion that it would be “world music,” and I am sure you get that a lot.

EM: Yeah, it wasn't so much about making a bold choice. It's more just like, I like making the kind of music that I like listening to, and I'm a sucker for international, remote collaboration, so how do I combine those things? But I think it's important for me to clarify. Not really for the sake of setting this project apart, but more for the sake of not being accused of false advertising, or not getting people to expect one thing, and then being disappointed when they get something that's vastly outside of their musical tastes. I think I used the word “avant garde,” but in retrospect it's more like alternative electro, and that covers quite a lot of ground, and every song could conceivably be considered a different genre, but there are still some commonalities. People should just listen to it.

GW: What is the best way for people to do that?

EM: We went live on all streaming platforms yesterday, which was Friday the 13th. January 13, 2023. So the album is available in non-physical form— bandcamp, soundcloud, stuff like that, and we actually have something else coming soon, and it’s actually related to the Antarctica song, and it has something to do with penguins.

GW: I am so excited! Penguins are my favorite animal.

EM: It has a lot to do with penguins. To say it has “something” to do with penguins is a gross understatement. Actually, if you'll hold on for a second, I will show you something.

EM: I will not give you any context for this now.

GW: Perfect.

EM: There's this little guy (shows a penguin puppet). And there's the super sized version (shows a penguin costume). More to come soon.