Somewhere in the mists of the early 1970s, a prog-rock enthusiast I rubbed musical elbows with for a brief time used to frequent an import record shop here in Cincinnati. In this enticing, below-street-level section of a multi-level downtown bookstore, he would find and retrieve pirate’s gold in the form of albums from emerging British and Euro prog-rock artists. Quite often, they were ones that the adventurous local underground FM rock station had somehow overlooked. Of course, he was also surely reading the British music papers for his inside track.

One such band that he breathlessly introduced to me was a keyboard-heavy and jangly, 12-string guitar group we all know now called Genesis. Sure, I liked all the piano, organ and interweaving guitar and flute bits OK, and the lead vocalist had a distinctly theatrical voice that reminded me of the lead singer from the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar. And, for what it was worth, there was even some lead guitar.

But my head was somewhere else at the time, I suppose, and that album just didn’t light much of a fire for me. (I had remembered the cover artwork – a classical painting being slashed by a knife – more than the music on it.) So I went on my merry, oblivious way, following other paths into the deep weeds of psychedelic and prog.

Fast forward to 1975: Thanks to a prog-heavy format of a low-power, regional college FM station about 50 miles outside of city limits I had just discovered, I was suddenly all abuzz over a new regiment of off-the-radar bands. (The station could usually only be heard clearly during evening hours, so that added a distinct thrill of discovery, too.) Leading the troops were Focus, Tangerine Dream, Gentle Giant, Caravan, Nektar, Camel and, yes, Genesis. (Perhaps needless to say, other prog standards like Pink Floyd, Procol Harum, King Crimson, Yes, and The Moody Blues were already locked in solid for me, but this radio station played them, too.)

Aside from the title track, I hadn’t even yet heard all that much of Genesis’ latest release of that preceding year, the double-LP concept album, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. But, thanks to the boundary-pushing college station keeping Genesis in fairly heavy rotation and to the eager prodding of a new musical friend at the time named Joe, the Genesis album that had finally broken through for me was Selling England by the Pound. (Joe was the photographer who took many of the lovely 1974 images reprinted in this article, and he generously had lent me the album for a fateful weekend of binge-listening in early 1975.) And not only did it become my personal portal to all things Genesis, Pound remains near the top of my personal life list. Happily, that’s something former Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett and I apparently have in common.

As of October 2023, Selling England by the Pound – which crept into the U.S. market on little cat feet in the Fall of 1973– marks its 50th anniversary. I could talk all day about the album, and maybe even write a book about what it means to me, but please let this brief synopsis of its singularity in Genesis history suffice. And, perhaps, if you haven’t already discovered SEBTP for yourself, you might seek it out and take a plunge into this alternate musical reality – rich in atmosphere, full of melody and dynamics, and laced with melancholy, social commentary, colorful word play, slapstick humor and Romanticism. No, it’s not at all rock ’n’ roll and certainly not yet what Genesis would evolve into by the early 1980s. But then, with early Genesis, an electrified kind of Victorian nostalgia seemed to be part of the mix.

The album opens with a plaintive, a cappella vocal by then-lead singer Peter Gabriel – in one of his more androgynous moments – as the voice of the mythical helmeted female warrior Britannia. (Umm, it wasn’t an isolated moment, either.) His naked first words are the posing of what now seems to be a timeless question, “Can you tell me where my country lies?

In writing the lyrics to this song, “Dancing with the Moonlit Knight”, Genesis were actually commenting on the socioeconomic state of England and resistance to the cultural pressures of Americanization in the 1970s. (This theme does pop up again throughout the album.) So, right from the start, tension is introduced over that seemingly tranquil plainsong melody.

The pace picks up, more narrative tension about economic misfortunes digs in, and the accusations fly. “You know what you are/and you don’t give a damn!” And then, over a Mellotron swell of choral voices, Gabriel issues his call to arms: “Knights of the Green Shield, stamp and shout!” The band breaks in big on the choruses, and then, – Boom! – they go full gallop on the instrumental, with volleys of zinging ‘70s fusion-flavored guitar and scintillating keyboards darting back and forth. It soon fades into a dreamy, extended soliloquy of slowly–arpeggiating acoustic guitars, textured electric guitar, flute, and hand percussion.

Now what was that all about? Genesis packed many layers and shades of meaning into this song, some lyrical, but many instrumental. And that’s the overriding brilliance of the entire album. Much is suggested by the provocative lyrics, and by the filigree and atmosphere of the songs. And the listener gets to fill in the rest in his or her imagination. Enter the Kingdom of Fantasy, where The Medieval meets The Modern, and ever-so-slightly controlled chaos ensues. But the flickering candle of Englishness still shines its light through it all. Somehow, it all feels strangely reassuring.

When asked in an interview with Grateful Web last year about what early Genesis adopters might have heard in their music at the time, Steve Hackett shared his insight that Italian audiences were among the first to embrace his band’s music deeply in the early ‘70s. And, he noted, there were many good reasons.

“They heard elements of opera and storytelling in our songs, I think. This was familiar to them, from the music and mythology they knew,” Hackett said of their early Italian fans, noting that the Genesis buzz in America “took a while longer” to cultivate.

A 1973 public endorsement from John Lennon – who was said to have heard Pound and commented in a radio interview that he enjoyed the farcical humor entwined in the songs – may have also given the band a timely boost. And, for some unexplained reason, their somewhat hallucinatory music also seemed to strike a chord with younger, blue-collar males – like me – across the upper Midwest in the States. (It is worth noting that female Genesis fans in the early 1970s were, sadly, in short supply.) So the Genesis fire caught first on the coasts, then slowly burned toward the heartland of the U.S. To say the least, they still were not an overnight sensation, but – thanks to frequent touring in the period – they finally started ‘getting there’.

“Genesis did longer songs that told stories, and also longer-form things, such as ‘Supper’s Ready,’ in which there’s a journey, a personal odyssey,” Hackett added, referencing the epic, 23-minute fan favorite from the 1972 album that just preceded the 1973-born Pound. And the band’s next album, The Lamb, would go into full-tilt Odyssey mode. But that’s another story.

Once again, with such longer songs as “Firth of Fifth” and “Cinema Show” on SEBTP, the themes of fantasy and mythology were never far away. “There are classical music elements in these long pieces, and I’m proud of those influences,” Hackett concluded. “I’m still very much a believer in long forms, because people seem to like pieces with many movements, many parts.”

While having the same chord progression and melody for parts of the opening and closing songs on the album might imply some overarching concept to the whole affair, Pound is less intentional than that, more generally thematic. Reportedly, the song order on Pound was reshuffled and reshaped from an original idea of one side-long track, similar to the multi-part fugue concept of “Supper” from their then-most recent album Foxtrot. Generally, the band was said to be averse to repeating itself in that way and opted for a different arrangement.

Working on this longer piece for a short period, the band resolved to bookend the LP with two longer portions of that starting piece about the Moonlit Knight. So, like a chunk of an asteroid breaking off and careening away on its own course, the highly changeable and climactic Side 2 finale “Cinema Show/Aisle of Plenty” – with its blend of CSN-style harmonies, Shakespearean name checking, spiritual yearning, navigating the stormy seas of life and shopping in a dangerous time – was born.

Still, the multi-part, character-driven, short-story approach did assert itself again on the 11-minute-long, mini-epic “The Battle of Epping Forest”. This chunky track – some band members have even called it clunky – was slotted in as the opening of Side 2 on the original LP. It gave singer Gabriel an outlet for voicing multiple characters a la Monty Python’s Holy Grail movie in this fast-changing and humorous tale about gang warfare in England at the time. (My hunch is that this may have been the exact song that struck Lennon’s funny bone.)

Work on the album – which took place over a three-month period – was said to be slow at first, but more songs began to fill in the spaces in between. For example, one track that was destined to be released as a single – and which actually generated breakthrough airplay and upwardly mobile sales for Genesis – was “I Know What I Like,” a song about a non-conforming, ne’er-do-well manual laborer. (“Me? I’m just a lawn mower/You can tell me by the way I walk. . . .”) It was built up from a trippy, Traffic-like, two-chord groove first fingered around on by guitarist Hackett during the Foxtrot era. In time, it was fleshed out with a synth drone, a Tony Banks’ chorus, flute and gorgeous, cascading harmonies.

With its modal topline melody and enticing electric sitar thread running through it, “IKWIL” bounces along hypnotically for four minutes. (Live versions have easily run twice as long.) Not a centerpiece of the album, for sure, but still a shorter song with Gabriel’s loopy spoken-word fragments and a happy hook that lent themselves to the singles format. And so, whether one heard the album or the single first, it became a sort of open door to the Genesis ‘wardrobe’ and the album for many first-time fans. In fact, the single became the band’s first Top 40 hit in the UK.

Mythical themes – from mortal fights between foxes and wolves to enchanted music boxes and magical mountain springs that could give Eternal Life – had always run rampant in the lyrics of Genesis songs. And the song from Pound that first caught my ear, “Firth of Fifth” – a song full of Earth and water symbolism and transformation – was certainly the mythological highlight on the album. (Neptune, to name the mythical entity of this song, makes his lyrical appearance in the song’s imperial processional verses.)

Written largely by keyboardist Tony Banks, this, too, was a multi-part piece. It announced itself with an intricate, solo-piano intro, It was then fully fleshed out with a churchy organ progression, anthemic verses and choruses, Crimsoneque flute intervals, and, of course, awesome flourishes of Mellotron. And, perhaps in a fitting Vivian Stanshall-Tubular Bells voice I should add, “E-lec-trick gui-tarrrr!”

As a Banks composition, “Firth” – which, in part, celebrates the primal power of rivers and the sea – showed the keyboardist at the peak of his skills. But, it must be said, it also provided Hackett the widest of canvases on which to paint the definitive solo of his career in the spine-tingling mid-section. And – thanks to the extra fat bottom provided by bassist Mike Rutherford’s use of Moog Taurus bass pedals – one almost feels the tidal swells of this piece more than just hearing them. (Especially in live performances, since there were limits to what vinyl could capture in those days.).

Notably, on their many follow-up tours through the years after Hackett’s 1977 departure, Genesis would often include portions or all of this signature song in their live sets, with guitarist/bassist Rutherford replicating Hackett’s iconic solo in his own approximate way. For his part, Hackett – to this day – includes an always-breathtaking performance of this song in nearly every one of his solo shows. And, as Hackett himself told Grateful Web just prior to the start of his current North American tour, it may very well be the ultimate early Genesis song.

“My ‘Firth of Fifth’ solo gives me the image of a bird flying high over the sea,” he said of that soaring solo. “It gives me a sense of freedom as it ducks and dives. For me, it’s a very emotional solo. I feel it’s Genesis music at its most evocative.”

When drummer Phil Collins emerged from behind his drum kit to take on the lead vocal chores for Genesis in the later ‘70s, after Gabriel’s famously sudden break in 1975, many fans were surprised to hear how well he could step into – some even say surpass – Gabriel’s role. But, as the song “More Fool Me” on Pound showed, the shining potential of Collins – a child actor and singer before dedicating himself to drums in his teens – was already there. On such a tender acoustic-guitar ballad as this – which was a change-of-pace Mike Rutherford tune in the midst of all the Mellotron melodrama and instrumental display on Pound – Collins’ winning tenor voice brought a welcome sensitivity and natural emotionality.

Seen in the rearview mirror, SEBTP seems to have caught Genesis at the peak of their creative powers, without hinting too much at the true struggle of its incubation process. For example, there was creative growth through cooperation and experimentation. Some members presented whole songs to the others, while others, such as Hackett, often brought in riffs or sketches and then hammered the ideas into joint creations. Also, new technology – such as the ARP Pro Soloist synthesizer – nudged its way into the band’s sound, giving Tony Banks a new weapon in his keyboard arsenal. (He used it freely throughout the album, but check out his stunning solo during the extended jam on the instrumental climax of “Cinema Show” to get a strong infusion of his keyboard wizardry with this instrument.)

But, naturally, as in any band, there were also reportedly tensions and disagreements at various stages, especially as they wrestled over some of the longer pieces and how to fit the album together. For example, there was tension about how long the album should be, and – to respect all the members’ contributions – some content was kept that made the single-disc album longer than a conventional LP. Due to the physics of record pressing, this was a trade-off that resulted in decreased audio quality, and some misgivings about this persisted after the album’s release.

Even some shorter passages, such as the Hackett- and Rutherford-penned Side 2 guitar instrumental, “After the Ordeal”, were a source of such discord. In particular, while first considering this piece, Banks expressed concerns over this instrumental’s structure, style and tone. Even co-writer Rutherford began to have second thoughts. Hackett himself has said that he had felt so strongly about inclusion of the multi-layered. classically-flavored track – the first Genesis song to feature him playing nylon-string guitar – that he threatened to leave the band if it were not used. So this deceptively tranquil musical interval had found itself at the center of a whirlwind of disagreement.

As it turned out, in the position in which it appears on the album – sandwiched between the madcap comic theater of “Epping Forest” and the dreamy but dynamic, multi-part Romantic narrative of “Cinema Show” – “Ordeal” serves as a timely, sepia-tinged mood shifter and stage-setter for the grand sweep to the end of the album.

Steve Hackett has remarked many times in interviews that of the six Genesis studio albums he worked on with Genesis, Pound remains his favorite among them, for a number of reasons. There is, of course, that experimentation with long-form compositions that he admiringly alluded to earlier, as well as the interweaving of electronic and acoustic instruments, a discovery of new musical expression and the seemingly full-ensemble interaction. In particular, perhaps it’s most because of the energy and passion behind the songwriting, as Hackett has called it Genesis’ most “heartfelt” album, and therefore the one of which he feels the proudest.

Interestingly enough, not everything Genesis had worked on during the Pound sessions made it to the final album. (Not enough room!) One leftover piece titled “Déjà Vu” – which Hackett has described as a “soulful little gem” of Gabriel’s – missed inclusion at the time. However, clearly still a believer in the bittersweet power ballad, Hackett released a version of it with Gabriel’s since-completed lyrics and guest vocalist Paul Carrack accompanied by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra for his first Genesis Revisited album, in 1996.

And then, almost 20 years later, when he and his hand-picked Genesis Revisited band were touring with a special live presentation of the entire SEBTP album in 2019, Hackett performed a new version of the song. Easing into the song after the main album was performed in full, GR vocalist Nad Sylvan would sing lyrics of the former Genesis lead vocalist in his most convincingly Gabrielesque voice and Hackett graced the song with his vibrato-rich melody lines. It definitely stirred thoughts of what might have been.

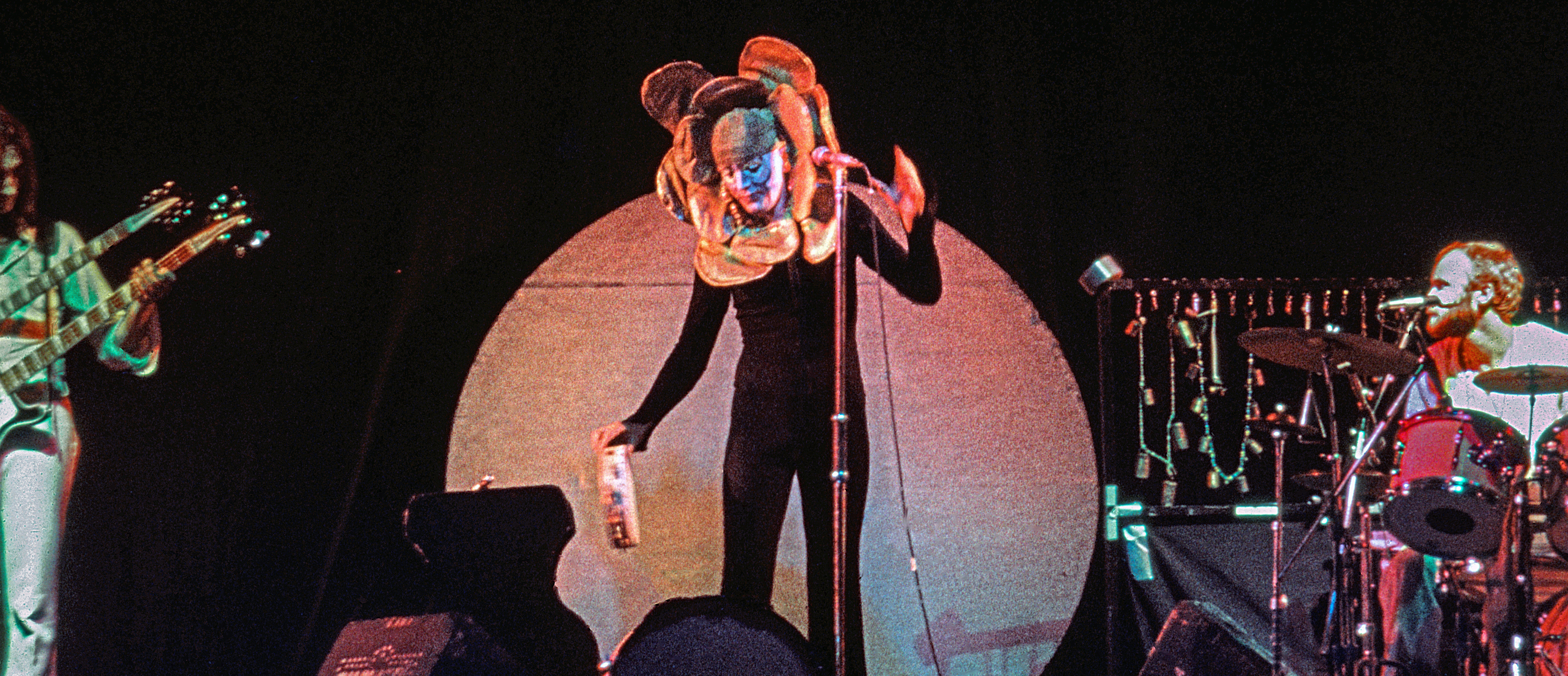

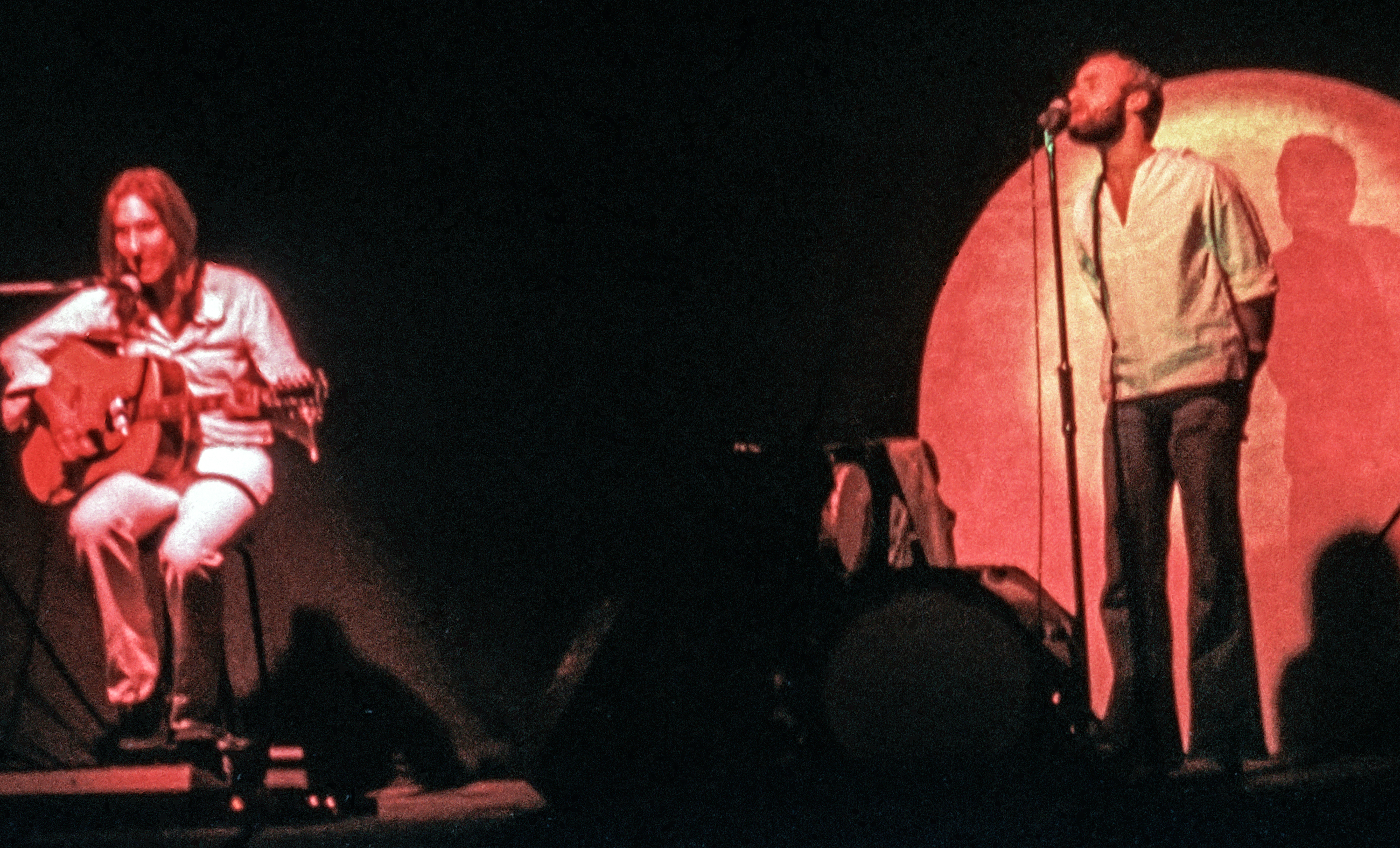

In the days of Foxtrot, SEBTP and The Lamb, Genesis were incredibly prolific and creative, almost in spite of what then seemed like almost constant touring. And this creativity spilled over in the stage productions, which by time of Pound had grown into more complex visual stage designs and lighting cues. And then, of course, there were the many legendary stage costumes for Gabriel’s storied menagerie of characters.

For the stage show of Pound, which also revisited some of the live highlights from previous albums such as “The Musical Box”, “Watcher of the Skies” and “Supper’s Ready”, Gabriel had many changes of head and face gear that helped to personify the characters in the songs. So, in very short time, this masterpiece of studio composition fed right into a ratcheting up of the stage show to a new standard for rock theater. They were also early adopters of the mirrorball, using it artfully well before other bands went mirrorball-happy in the later ‘70s.

Judging from the photos my now-deceased friend Joe had taken in early 1974, I can only imagine that the Selling England by the Pound tour was truly something to see and hear. But, unfortunately for me, due to my own slow Genesis learning curve, I missed the Gabriel years in the band’s live shows and didn’t see my first Genesis show until 1976, when Phil Collins transitioned from his original night job as drummer to lead singer and front man.

As a landmark of progressive rock, Pound has also been a longtime favorite among the legions of Genesis fans and also the band’s musical descendants. For instance, the Montréal-based Genesis legacy band, The Musical Box, which specializes in recreating fully-authorized live stage shows and music of early Genesis, has been authentically been performing Selling England by the Pound stage shows since their first shows in 1993. (The band, which has done full re-enactments of several other major early Genesis tours, will be launching their latest production of SEBTP, with a new tour that starts on Nov. 2, in Sherbrooke, Quebec. This tour also coincides with the 50th anniversary of its namesake album.)

Not everyone embraces the tribute band experience, I know, but I can offer firsthand testimony that attending a TMB show is quite like stepping into a time machine! Through TMB’s devotion to capturing the live experience of Genesis, so many have been able to experience the magic of the Gabriel years for the first time with their faithful recreations. Reportedly, Genesis vocalist Peter Gabriel once took his children to see one of TMB’s earlier Pound performances just so "they could see what their father used to do". And even Hackett and Collins have both joined TMB on stage to play encores with TMB on a couple of special occasions over the last 20 years. So if one has any doubts as to TMB’s authenticity, perhaps those personal endorsements from the music’s creators just might change a mind or two.

Undoubtedly, Selling England by the Pound is a legendary album that has stood the test of time, much-loved by the fans and various band members alike for the mark it has left on their lives. Delightfully, it seems to tickle the hearts and minds of so many with its warmth and whimsy, and it will, presumably, continue to do so as long as there are fans of progressive rock to listen to it.

So, you may ask, will rock music fans really still be listening to Selling England by the Pound 50 years from now? Well, I’d be 119 by then, but, on the off chance I should still be around, I know I’ll still be listening be because I learned a long time ago to know what I like and to like what I know.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Joseph Stercz, a fellow prog traveler who nudged me more deeply into the prog metaverse.

For more information about The Musical Box and their upcoming world tour of the Selling England by the Pound show, please visit the TMB website: http://www.themusicalbox.net.

Steve Hackett is currently touring in North America with his acclaimed “Foxtrot at 50 + Hackett Solo” tour. This tour will continue into mid-2024. Then he will begin a new show in the Fall of 2024 titled “Genesis Greats, Lamb Highlights & Solo”. For complete information on tour dates, please visit the Hackettsongs website: http://www.hackettsongs.com/tour.html.