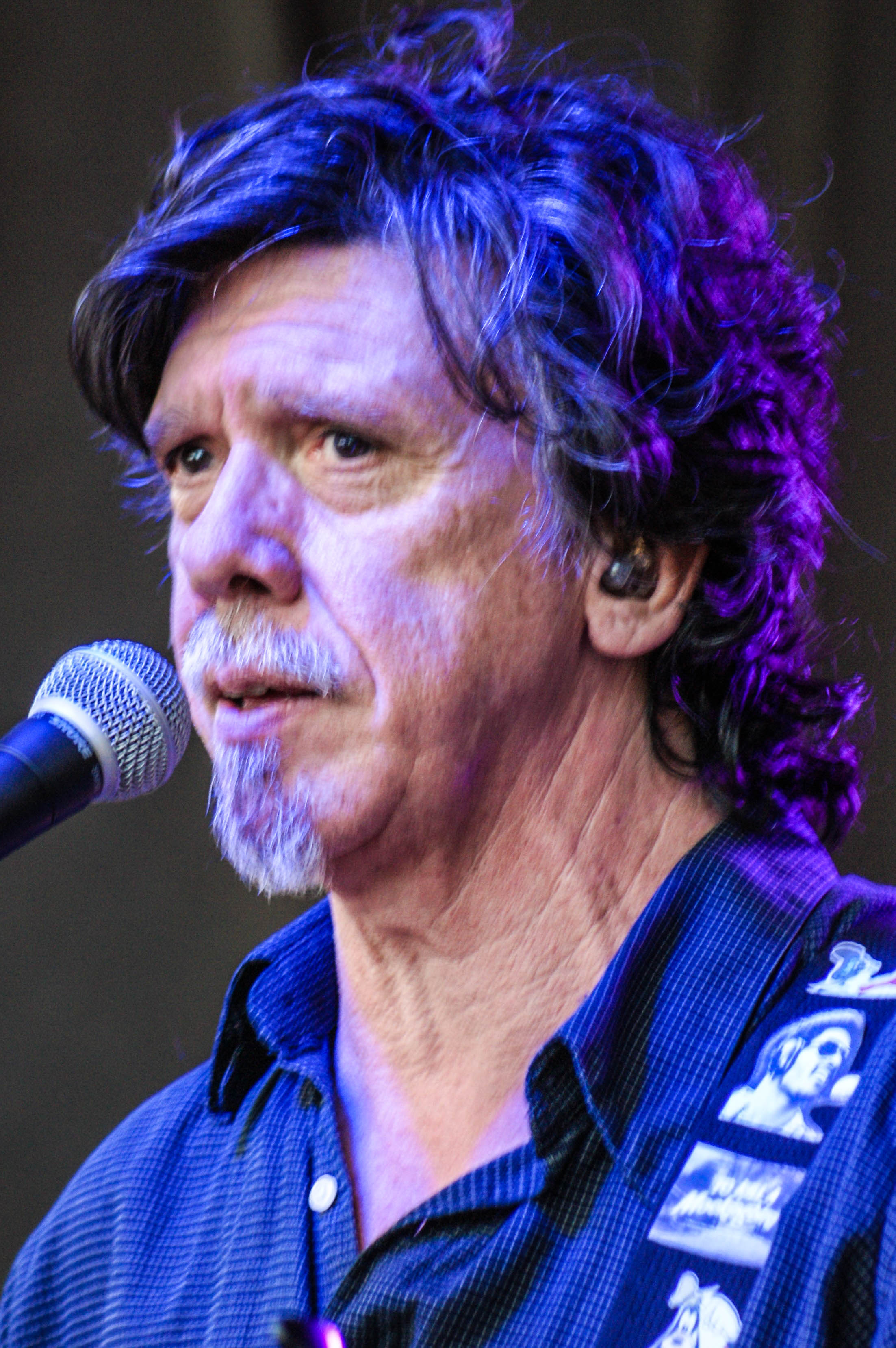

Next week, Mickey Hart will make an historic appearance at the 10,000 Lakes Festival. This will be the first year that two founding members of the Grateful Dead will be on the same bill, though they will play on different days.

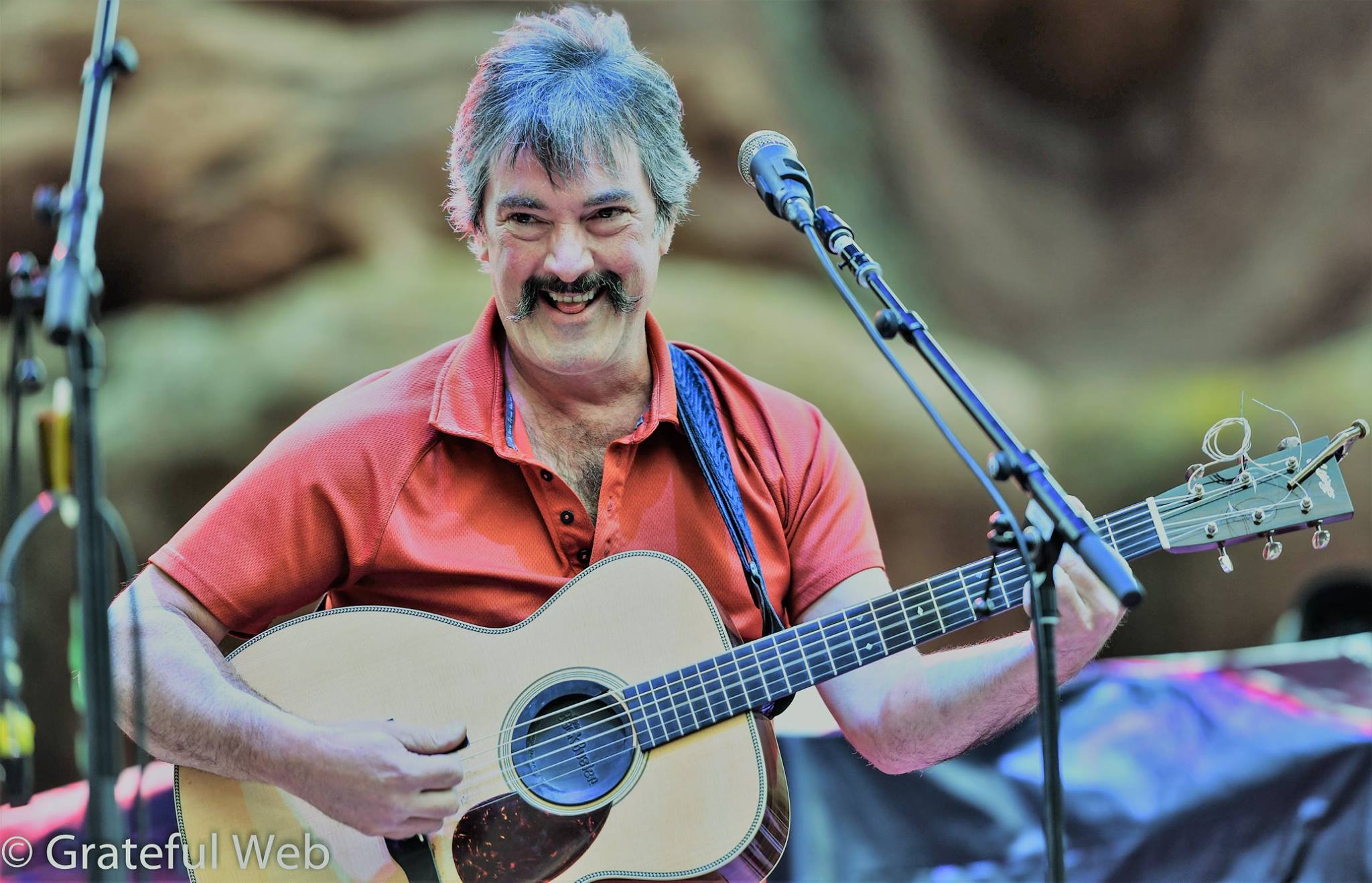

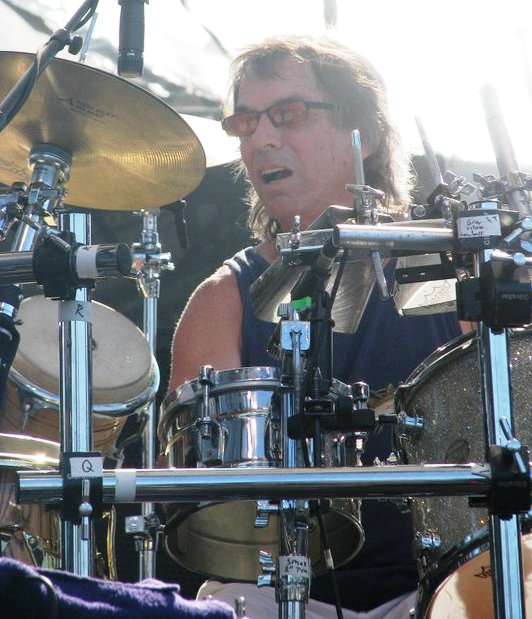

This year, Hart will be bringing a new incarnation of his Mickey Hart Band, which he has constructed from time to time when he wanted to explore rock and jam more intimately. The 2008 version of the band features Steve Kimock (The Other Ones) on guitar and pedal steel, George Porter Jr (The Meters, Porter Batiste Stoltz) on bass, Kyle Hollingsworth (String Cheese Incident) on keys, Jen Durkin (Deep Banana Blackout) on vocals, Walfredo Reyes Jr. (Carlos Santana, Jackson Browne, Steve Winwood) on drums, and Nigerian talking drum master Sikiru Adepoju (Planet Drum, Global Drum Project).

The band formed to complete a 20 city tour that will end at the 10,000 Lakes Festival. Band members will offer fresh takes on Dead favorites like "Fire on the Mountain" and "New Speedway Boogie," as well as songs by Robert Hunter who wrote for another Hart some-time band, the Rhythm Devils.

A master percussionist, Hart has traveled all over the world to seek out indigenous drummers and their instruments and explore their varied drumming styles. This resulted in the book Drumming at the Edge of the World and the record At the Edge, which he released in 1990 with a collective of world drummers that he had come to know and respect. A year later, the book and album, both titled, Planet Drum, followed. Planet Drum became a phenomenon, holding the position of #1 on the Billboard charts for 26 weeks, something that a drum-driven record had never done. The Recording Academy responded to this unprecedented recording by creating a new Grammy category to honor the percussionists' efforts, presenting Hart and his fellow drummers an award for the Best World Music Album that year.

When Hart and some of his drum friends reunited for the Planet Drum Reunion Tour in 2006, he wanted to try that grand drum experiment again. Recorded at Hart's Sonoma County Studio X, the Global Drum Project CD featured Indian tabla virtuoso Zakir Hussain, Puerto Rican conga giant Giovanni Hidalgo, Nigerian talking drum master Sikiru Adepoju, and Hart. Other musicians assisted, including Taufiq Qureshi on percussion and vocals, Niladari Kumar on sitar, and Dilshad Khan on sarange, an Indian stringed instrument. As a tribute, Hart sampled vocals by the late Nigerian drummer Babatunde Olatunji, who was showcased on the original Planet Drum recording.

Studio X was the ideal space to record this project. "The room is a huge barn," said Hart in a phone interview. "This is where my collection also resides. You can't call for these kinds of drums; some of them are one of a kind."

With these instruments and many that his fellow drummers brought with them, Hart and the percussionists began to craft something brand new, something totally different from Planet Drum. "That was more in the acoustic world," he explained. "This is more reflective, electronically, of the world we live in. These are the sounds around us."

Hart included what he called "found sounds." "Some of it is metal junk from a junk yard," he admitted. "Some of the instruments don't even have names." On the cut, "Dances with Wood," Hart and his fellow drummers experiment with forest downfall, redwood stumps, and roots. "You play mallets on it. You play sticks on it. You play fingertips," he said.

Hart included what he called "found sounds." "Some of it is metal junk from a junk yard," he admitted. "Some of the instruments don't even have names." On the cut, "Dances with Wood," Hart and his fellow drummers experiment with forest downfall, redwood stumps, and roots. "You play mallets on it. You play sticks on it. You play fingertips," he said.

And, Hart even does some DJing from AM radio, something you would never expect from the master of organic drums. He replaced flashy drum solos with soundscapes. Hart explained, "We just wanted to get into the zone and take people on a trip...When you play with percussionists of this caliber, there are two ways it can go. It can turn into a giant drum challenge with everybody trying to outdrum each other. But the egos have been put aside here....Everyone was very committed to the groove."

Though this recording was done in Hart's studio, it was as if it were in a live setting. Anything can happen in a live setting. Sometimes, magic happens. You get a new feel for something as you're performing it. "These tracks were laid down with that kind of spirit," Hart said. "We didn't overwork them or anything. We just didn't beat them to death. A lot of them were first takes. That's the way I like to make the music. I don't like to sit with it and sterilize it. This music has a certain good groove feeling to it..... The composition came from deep down…. What we set out to do was to say something exciting, new, and different, something that would resonate with each one of us, and hopefully with other people."

One particular cut on that album, "Tars," has a deeply spiritual element to it. When this was mentioned to Hart, he said, "It certainly does have a spiritual heart to it because that was the way it was played. A lot of love and a lot of care was taken in creating it. That's what music is. It is a bridge to the spirit, the sacred dimension of spirit places, the zone. We were trying for the trance..... It's kind of a tricky business without falling into the new age category."

Hart, though, sees his music as something more than just a CD he's producing or a concert he's giving. It is something that has a soul. "It's not so much what we do, but it's what it does to you," He said. "If you can stir somebody's emotion using the instruments you love the most, then it's successful....I think of all the CDs that Zakir and Sikiru and Giovanni and I have done over the years, I think I'm most proud of this."

Whether it is recording or giving a concert on stage, Hart feels that music comes from someplace deep within. "It is a spiritual outpouring," he said. "This music wasn't composed. We'd just sit there and look at each other or we'd have a notion and we'd play it and someone reacted to it, then another person reacted to it. All of a sudden, it became something, something we can't define, something that we have no name for. When it's part of that Great Mystery, it also has great wonder. You know it as what we refer to as magic. I'd like to think that these grooves came from that zone and our collective unconscious, stuff that we've heard over all of our years that somehow has some resonance. When we sit together, it has meaning in that respect. It's like little bits of your subconscious rising to the top. That's what this music is....It's not written down....You can't compose this music. This is all improvisation in nature."

Whether it is recording or giving a concert on stage, Hart feels that music comes from someplace deep within. "It is a spiritual outpouring," he said. "This music wasn't composed. We'd just sit there and look at each other or we'd have a notion and we'd play it and someone reacted to it, then another person reacted to it. All of a sudden, it became something, something we can't define, something that we have no name for. When it's part of that Great Mystery, it also has great wonder. You know it as what we refer to as magic. I'd like to think that these grooves came from that zone and our collective unconscious, stuff that we've heard over all of our years that somehow has some resonance. When we sit together, it has meaning in that respect. It's like little bits of your subconscious rising to the top. That's what this music is....It's not written down....You can't compose this music. This is all improvisation in nature."

He also explained the difference between mainstream radio music and what he has tried to create with the drum. "How do you make a little pop ditty that has been done before or a power chord into something that moves your soul and makes your heart beat faster and is meaningful? This music was meant to go to a different space, some place that we've never been before. I certainly have never been to this space. I don't even know where it came from, nor do I even care."

This is Divine play that Hart is speaking of. Musicians have this utter joy of adding this and sharing that and reacting to some other musician's music, creating a conversation back and forth. That joy and creativity digs deep into the spiritual realm. In the case with the Global Drum Project, superior musicians came together and pulled from the subconscious, from the soul. It is magic in all shapes of that word. Hart and his fellow drummers, especially, help all of us come closer to creation, making us feel that we can almost be a part of the process. "That is music's purpose, to be able to make you vibrate with this. It's called rhythmic entrainment," Hart said. "You're getting in sync with the grove, with the sounds. It becomes a spiritual experience. That's exactly the power that is the real essence of good music."

This is Divine play that Hart is speaking of. Musicians have this utter joy of adding this and sharing that and reacting to some other musician's music, creating a conversation back and forth. That joy and creativity digs deep into the spiritual realm. In the case with the Global Drum Project, superior musicians came together and pulled from the subconscious, from the soul. It is magic in all shapes of that word. Hart and his fellow drummers, especially, help all of us come closer to creation, making us feel that we can almost be a part of the process. "That is music's purpose, to be able to make you vibrate with this. It's called rhythmic entrainment," Hart said. "You're getting in sync with the grove, with the sounds. It becomes a spiritual experience. That's exactly the power that is the real essence of good music."

Hart explained further, "Music is invisible. You can't see music. Music is controlled vibration. It lives in the vibratory world. It's the vibratory arts. If you can harness the energy of vibration and get a pleasant experience as well as a spiritual one, not only for the player but the listener, then, that's what I call a rewarding experience. We hope this makes a better world."

Part of making a better world is Mickey Hart's participation in the Endangered Music Project, a Library of Congress undertaking. "I am on the board of the American Folklife Center there. I'm a trustee," Hart said. "What we're trying to do is digitize rare and endangered music. The material on which the music was recorded, back even to 1890, is, for one reason or another, decomposing. The idea is to get it all into the digital domain as fast as possible while we have the chance and give it back to the cultures it belongs to. Also, the moneys raised from the sale of the music goes back to the different cultures." The Endangered Music Fund helps re-record the music and then repatriates it back to the culture of origin, giving it some worth in the process. "When people in Indonesia realize that people in America are buying their music and appreciate and love it, they would practice it more," Hart added. "We're giving back the old forms. When we give them their CDs, it's like giving back a long lost relative or someone they haven't seen in forty, fifty years. It's very precious to them because these songs contain the hopes, the dreams, the fears of thousands of years of evolution in cultures.....These songs were ripped away from them for one reason or another: colonization, missionization, or wars or Exxon putting a pipeline through their backyard or destroying their rain forest or whatever. This kind of tips the scales back the other way."

It is to be sure that whatever kind of music Mickey Hart is making or helping to preserve is music that is deeply rich and profound and at the heart of many cultures. Make every effort to see Mickey Hart live when you can. And, the 10,000 Lakes Festival is an ideal setting.