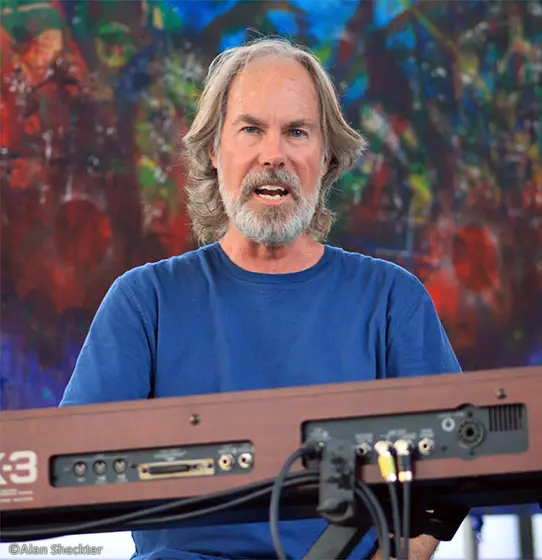

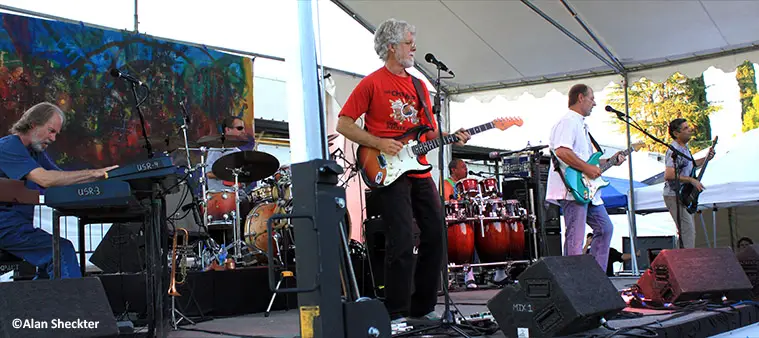

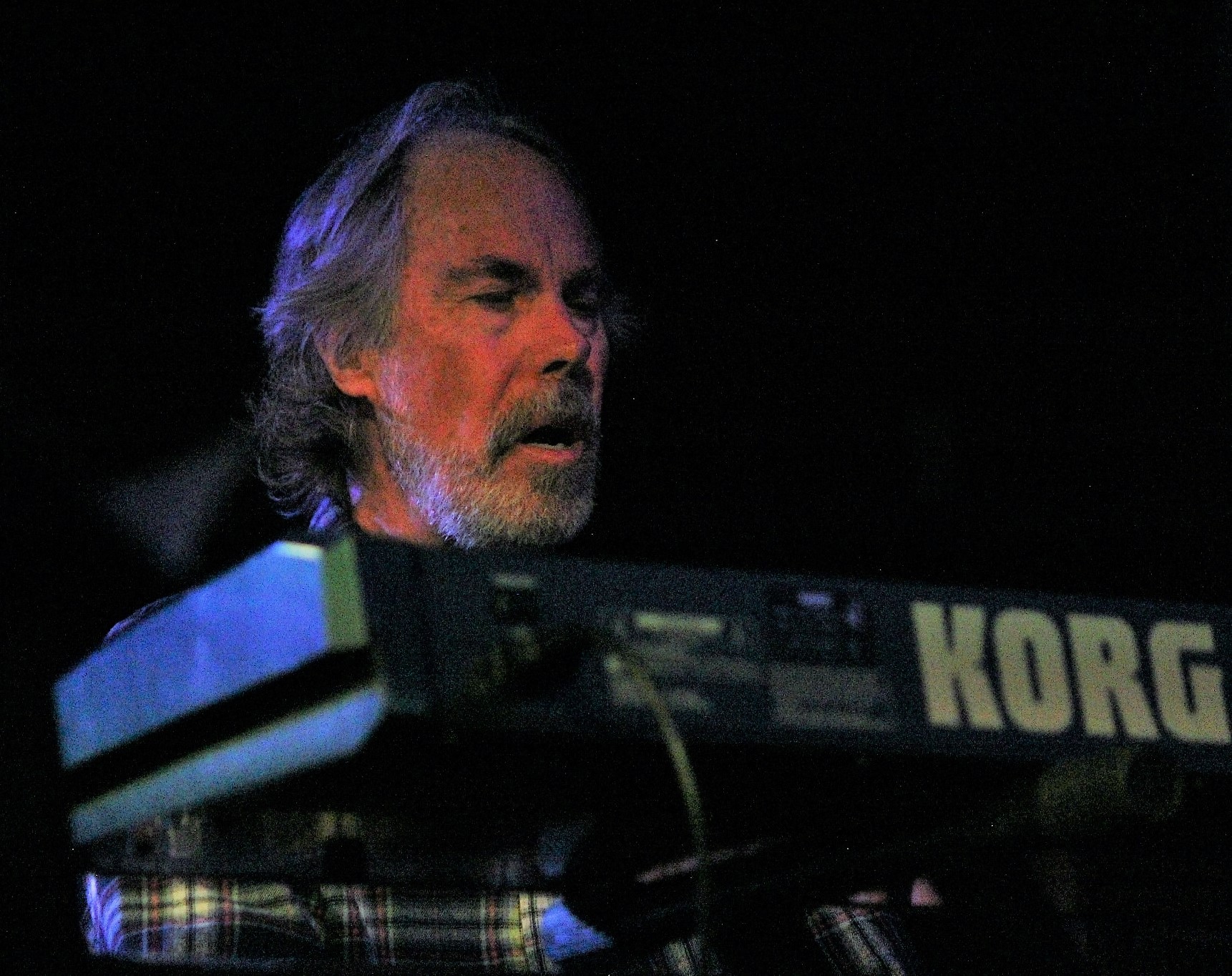

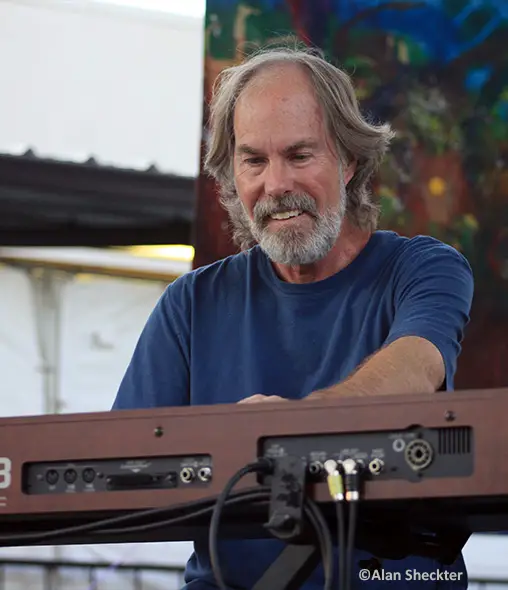

Grateful Web recently had the honor of speaking with Bill Payne about the upcoming milestone of 50 years of Little Feat in 2019. Payne’s depth as an artist goes much farther than Little Feat’s founding pianist, co-songwriter and vocalist. A photographer, poet, one of the hardest working and best damn American rock musicians since the 1970s. It’s no wonder that the bands he’s influenced (Phish, The Black Crowes, Bonnie Raitt, and Leftover Salmon to name a few) speak of Payne as a foundational player of the jam universe. In conversation with Dylan Muhlberg, Bill opened up about Feat’s formational years in Hollywood by way of Frank Zappa, the many influences that brought together their fundamental sound, and the muses that continue to fuel his creativity.

GW: You spent most of your upbringing in Ventura, California. In 1968, what music were you listening to? Were you already acquainted with Lowell George, Roy Estrada, and Richie Hayward?

BP: I was not acquainted with any of them yet actually. 1968 was a hell of a year because we lost Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. I’d played a rally for Robert Kennedy, with a local band. At the time I was probably up in Santa Maria, but we did play that gig in Ventura. And about a month later he was assassinated. It was a very tumultuous time.

Some of the music I was listening to at the time was on the radio. KSON radio out of San Francisco. Back then a lot of underground radio was taking place. I must have been listening to some of The Band at that point, I think “Big Pink” was 67’ or 68’. Just the normal stuff for us which has now become so iconic. I didn’t realize that when I was growing up was a golden age of music, at least for rock’n’roll and the arts broadly. It was also a scary time with Lyndon Johnson then Richard Nixon in office. It was similar to the state of things now. When we woke up every morning that was the feeling. Chaotic and tumulus times tend to aid the arts.

GW: Indeed. I’d like to see more artists contemporary coming out with topical songs and standing up for what they believe in and reflecting that in their music.

1969 was the year where Little Feat came together. What was the genesis of Little Feat in those early days? You were signed to Warner Brothers only two years later as Lowell already had some clout through his stints with Frank Zappa, if I understand?

BP: The genesis of it was when I met Lowell George in 1969. I had originally gone to meet Jeffery Simons who was in the group called Eureka. I’d heard that group in Los Angeles as part of a concert that Frank Zappa put on. I called those two labels that Zappa headed up, Bizarre and Straight, and I spoke to someone there, but it took several times before I could actually get their attention [laughs.]

I finally got ahold of Jeff, and we met at the Tropicana Hotel off Santa Monica Blvd, and he goes, “Oh you play keyboards too?! I also play keyboards along with guitar. I don’t think it is gonna work!” – But then he suggested I get in touch with Lowell George instead. I was ostensibly trying to meet Frank Zappa but was familiar with Lowell as he played on Zappa’s Uncle Meat (1969). So that’s how I met Lowell, and we began playing together and doing our thing.

We went through about six bass players in the summer of 1969, and Paul Barrere was one of those who auditioned, even though was primarily a guitar player. Lowell would say, “It’s simple! It’s two less strings.” I threw a chart in front of Paul that Stravinsky himself couldn’t have read, which was a Zappa-esque piece that we could barely play, and neither could Paul, so we kept searching. Once Roy and Richie gravitated towards us, we spoke to a lot of producers, Ahmet Ertegun of Atlantic Records was one of them. He told us, “Boys, the material, it’s too diverse.”

So, when you listen to the first Little Feat album, and you hear how eclectic that album was you could only imagine how off-the-rails that early stuff we presented to Ahmet Ertegun was! At the time I didn’t realize he’d produced Ray Charles and all these other legends.

GW: On Little Feat’s self-titled debut record in 1971 you are credited or co-credited as writer of six tracks. What was the collaborative relationship like between you and Lowell in those early days? Did you feel invited to bring previously penned originals or were these songs created in the formative years of the band?

BP: I honestly hadn’t written that much up until that point, so this was truly the beginning of my genesis as a writer too. Lowell and I hit it off really well on that level. “Truck Stop Girl” was one of the first songs that we worked on that made sense. Later “Strawberry Flats.” I would come up with these ideas lyrically, and we’d toss around ideas back and forth. It was a wide-open time, and by the time we’d hit Sailin’ Shoes (1972) that period of good will had begun to evaporate as Lowell wanted to take a stance and writing his own stuff, which was fine. He was writing some truly wonderful tunes at the time. He only got better and better. I kept writing too. I was instrumental in bringing out certain arrangements.

GW: “Tripe Face Boogie,” immediately comes to mind. A song performed by Lowell but arranged by you.

1972 brought drastic lineup changes with the departure of Roy Estrada and the addition of a second guitarist and vocalist in Paul Barrare, Bassist Kenny Gradney and percussionist Sam Clayton. This was the lineup that would ultimately bring the celebrated album Dixie Chicken (1973). Can you describe how the band dynamics shifted during that period?

BP: It was indeed a very dramatic lineup change. Let’s start with the addition of Kenny Gradney and Sam Clayton, who at the time were defined by where they came from, which was Delaney & Bonnie. There’s a movie called Festival Express which documented that legendary train ride across Canada [in 1970] with Janis Joplin, The Band, and the Grateful Dead. But Kenny Gradney, in Delaney & Bonnie is the first and the last person you see in that film. Initially, it was just Kenny who came into Little Feat.

I remember we were at my little apartment in West Hollywood right on the border of Beverly Hills. Richie lived down the way too. I had Lowell’s grandmother’s grand piano that I’d written “Tripe Face Boogie,” along with Richie on. This one day with Kenny at the piano, anything I threw at him he’d just play right back. He said he had a friend that he wanted to bring into rehearsals, and that was Sam Clayton. We had our first gig together over in Hawaii at this Crater Festival. There were 30,000-40,000 people at that festival on Oahu, and from then on Clayton was in. Our next gig was at the Fox Theater in Long Beach. The dynamics that those guys brought in from Delaney & Bonnie was this rootsy music, and Lowell and I were definitely into that. Paul Barrere came from a blues background. Richie and I went down to a club to hear Barrere play and we brought him in before Roy left the band. Having that second guitarist took some of the burden off Lowell to play lead and rhythm because our music was getting more sophisticated on some levels and more rootsy on others.

The way things worked out, it was the perfect setup for us to gauge New Orleans music which we really loved. When I met Lowell, I was already aware of Clifton Chenier, but with the eclectic dynamics forming between myself, Lowell, and Richie it was just a matter of mining things. You hear those influences in songs such as “Dixie Chicken,” and “Fat Man in the Bathtub.”

We didn’t record the blues in studio until later, but those were always foundationally part of our process. Little Feat has always been a platform for exploration. Little Feat’s usage or utility to bring in material that was at our fingertips began to genre-blend instead of doing something straightforward. That was the platform of freedom we had. It was incumbent that as musicians we could voice through our writing and our playing, which not only kept us balanced as a group but pushed us to be better musicians. We were working and playing thankfully with a lot of people who challenged us. I go through that to this day, I’ll be seventy in March, and I still haven’t lost that desire to push boundaries.

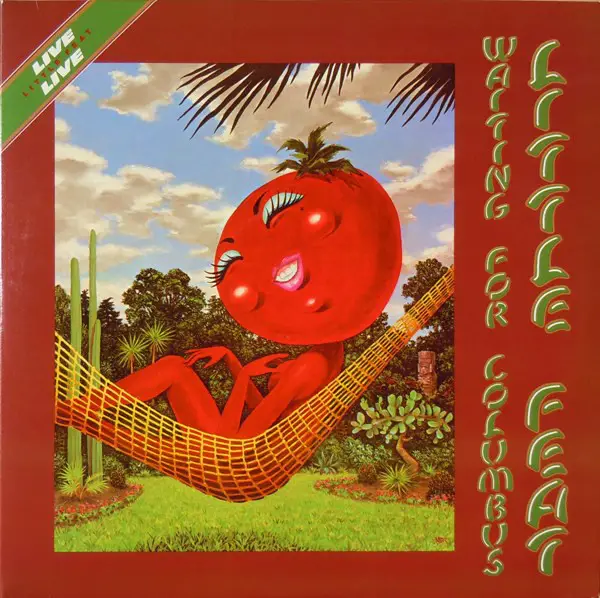

GW: I wanted to focus on this idea of “jamband,” from the lens of the 1970s. Original tunes of yours such as “Oh Atlanta,” and “Time Loves A Hero,” uniquely blended piano and synthesizer, which became not only a signature characteristic of Feat, but a beacon for a new generation of inspired players. For example, Phish covered Waiting For Columbus [acclaimed 1978 live double album] in its entirety at a show in Atlantic City, and pianist Page McConnell credited you and Little Feat as a cornerstone influence.

Was the term “jamband” floating around in the 1970s? What was your impression of the movement that ultimately spawned in the late 80s?

BP: It’s a great and wide-ranging question. The jamming aspect of it was pre-Little Feat obviously. I learned it through some of those FM Radio stations, by going to concerts at The Family Dog in San Francisco or going to The Fillmore to hear the Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Moby Grape, Muddy Waters, Lightning Hopkins, The Charles Lloyd Quintet. Bill Graham would throw together these shows with wildly disparate range and musicians. It was just wowing.

Oddly enough, when we did what we considered to be “jammy,” we’d sit on the A-chord for a while, and I found that boring. I grew up playing classical music, and my teacher Ruth Newman in Ventura wrote out the Davy Crockett theme for me in a way that taught me to read sheet music without taking the magic out of playing it. She allowed me to play by ear as well as read. Playing that way on both levels allowed me to excel. Take a song like “Strawberry Flats,” for example, which has a lot of parts and movements. There were other areas of inspiration that I drew from, country music and again The Band. In a jam when you’re just doing an A-chord what you’re looking for is a way to empty things out to build them up again. It wasn’t much different ultimately from what the guys in Dixieland music were doing, with the patterns you were playing with or against. That applied to everybody.

Playing with Phil Lesh [featuring Bill Payne, Paul Barrere, Robben Ford, and John Molo] in 2000 was one of the most memorable times in terms of learning to control a jam. That guy knew what he was doing, and because we're playing Grateful Dead music, and other such songs besides Little Feat like Steely Dan, those were really sophisticated changes that you could incorporate and take off on. Not just chordal changes but rhythmic ones too. But [collaborating with Phil Lesh & Friends] was way off in the distance, this was just the 70s.

Thinking back to the 70s it feels kind of like covered wagon stuff for me [laughs]. The blues was my savior in keeping focused in a rock’n’roll band because the literature of blues was so wonderful and deep. I’d listen to the record Back Door Man by Howlin’ Wolf with Willie Dixon. I was listening to jazz, to Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, to James Brown Live at the Apollo Theater. And then there were humorous songs such as “Alley Oop,” with that comedy built in, which was what Zappa was garnering. Sophisticated changes from the classical side. Then there were the “freak outs,” which was another aspect of jamming but not just musically, but all about the full experience. Vince Herman of Leftover Salmon is still doing that.

The foundation was already in place; it was a matter of searching it out and how we identified it to our art. That was part of this big clusterfuck which was going on through the 70s. It was sexual; it was musical, it was art, it was food. It was, “do you live in the city, even if you hate living in the city?” It was the Vietnam War. It was a complete and utter mess. We were there as artists due to share with others what our take of what we were going through. To boot, we were all young and didn’t know who the hell we were.

That’s where that synergy came in, and it’s still there. The music of Little Feat, The Allman Brothers and the Grateful Dead has now been around for five generations. Nothing had ever lasted that long. It spoke loudly to people not being caught in the definitions trap. You want to hear musicians who are willing to step out and voice things that might challenge their audience. We were all doing that. Pop music was set aside to handcuff or to liberate depending on who you were as an artist.

GW: Little Feat wasn’t inherently a psychedelic band, though there were certain moments of it. This was “get off your ass and dance” music that was hugely popular and approachable. You heard it with the band in concert and on studio albums such as Feats Don’t Fail Me Now (1974) and Down on the Farm (1979). The live album Waiting for Columbus documented the broad sound, celebrated songbook, and unstoppable momentum behind Little Feat, with Tower of Power horns to boot!

That said, Little Feat and the music world took a huge loss with the tragic, untimely passing of Lowell George in 1979, a time which was a music peak for Little Feat. The band wouldn’t play together again until a triumphant comeback in 1987. What were your feelings revolving around Feat in those years between? As a successful solo artist, was it difficult to ever imagine Feat without Lowell?

BP: I did not see a Little Feat after Lowell’s passing. I took refuge in playing with James Taylor and Linda Ronstadt. I was fortunate to have a reputation for being able to sit in with other bands. Regardless, Lowell was a tremendous loss on many levels for me. I loved the guy; I hated him, I hated what he was doing to himself and others. I probably wasn’t very happy with what I was doing either in terms of trying to sort out who I was, how we fit into things. It was a really disjointed time, but I had certain things that I was holding on to. When I was out with James Taylor, working with guys like Dan Dugmore, Rick Marotta, and later with Russ Kunkel, I didn’t realize the impact that Little Feat had on other players. I never thought, let’s put Little Feat back together.

There was this natural apex building which finally arrived when Little Feat came together for a one-off to commemorate a room called The Alley. We did it in part for Lowell, in part for Little Feat, and in part as a homage to The Alley. When we played, we were trying to replicate these songs which were in our catalog but not in our minds. It felt like trying to sing a distant Christmas Carol. It then dawned on me how intricate our music was. The intricacy was adorned and clothed in a cloak of something that felt perfectly natural to play.

To this day, when bands like Phish or others perform Waiting for Columbus or the songs of Little Feat in general, they all say the same thing; “it wasn’t that easy to play!” It sounds easy, but it’s not easy. We didn’t do it to trip anybody up. [Laughs] We didn’t know, we were just doing what we did. It turned out that this was very similar conceptually to what The Dead and Steely Dan were doing. Even though it was markedly different kinds of music on many levels, the traits that were similar was that one verse you’d play a passing chord one way, the next time you’d get there you’d play it a different way. These are the details that some musicians who try to replicate might dumb down. I’m speaking on behalf of myself though I think Fred Tackett and Paul Barrere would like to see those intricacies kept. That was one of the great joys of being able to write songs with Robert Hunter in recent years, which is a different subject.

GW: Little Feat never lost their vigor, and you formally brought in Fred Tackett as second guitarist (and trumpeter) to Paul Barrere and Craig Fuller on vocals from Pure Prarie League to compile the lineup which would record Let it Roll (1988). This was a triumphant comeback. The camp of folks who closed their minds to a post-Lowell George Little Feat were hugely missing out. The songs of that came with the revival, “Hate to Lose Your Lovin’,” “Cajun Girl,” “Rad Gumbo,” “Texas Twister,” to name a few, were at the caliber of the tunes the 1970s Little Feat put out.

BP: To speak to that critical camp, while I respect their view, they’ve boxed themselves into a closet. While It’s understandable that they’d cut themselves off, the reality is the songs, and you’ve mentioned some of the songs that bolster that reality. Where else could you hear, “Hate to Lose Your Lovin’” or “Representing the Mambo”?

I thought long and hard about whether we should put the band back together, whether it should even be called Little Feat. It came down to that we were going to be in competition with ourselves, and you can’t erase the past. Lowell is part of this family that we call Little Feat, family’s loose members and it’s a sad part of life. I didn’t realize until much later, but we never lost Lowell, as he will always be a big part of who we are as a band. He resides in every note that I play with Little Feat. It’s definitely because of the influence we had on each other.

Here’s a perfect example of flawed expectations in this nature. When I was young, I went with some friends to see The Yardbirds, and we were fully expecting to hear Jeff Beck on guitar. We discovered Beck wasn’t there we were pissed off until we heard the new guy who came in to play guitar. That was Jimmy Page. I’m sure that some of the people who were waiting to hear Jeff Beck didn’t accept Page until later, or maybe never. Think of classical music as an example, you’re not going to a symphony to hear the artists who wrote the compositions, but the musicians who are performing it then. Music is defined by musicianship, honesty, and integrity. When Little Feat rolls on all cylinders, it’s still the same feeling.

I’ll be in Jamaica this year in January with Little Feat and in March to celebrate 50 years of this band. I’ve been playing with the same cats I’ve been playing with since 1972. I don’t ever treat any of this stuff lightly. I truly hope when we do another record that we still have some great vehicles to write from.

GW: And since the band got back together in 1987 it’s been quite the journey. Shaun Murphy contributed vocals for over sixteen years solidifying a unanimously adored Little Feat into the 2000s.

The music world lost another great when Richie Hayward passed in 2010. Hayward’s drum tech Gabe Ford has stepped up as touring drummer for Little Feat since. Upcoming in 2019 you’ve announced a handful of dates commemorating 50 years of Little Feat. Where is your headspace going into this milestone year?

BP: The question really becomes, how committed are we to doing this? If we’re just going to go out there in a lackadaisical manor, I’m not interested in performing. I felt lately, in the last year or so, a revived spirit with Little Feat. This is why now is the time. Paul and I speak about it, and we talk about the new material we’re writing and potentially putting out a new record. I’d love to hear something that’s a rootsy record made by this group, played in a way that very few people could play like. I’d love to bring in some extended members of Little Feat family, such as Larry Campbell.

I’ve been working some new songs that would be great with Little Feat or alone. After working with Robert Hunter, I’ve been collaborating with this wonderful lyricist Tom Garnsey, and I’ve written three or four songs with my son Evan. The magic and the cinematography are in the lyrics. I don’t feel any limitations anymore with what I do. These days I’m listening to a lot of Wayne Shorter, Martha Argerich, a classical pianist from Argentina, even digging into some Ray Charles, Howlin’ Wolf, JJ Cale. World music, Cuban music, Africana music. I want to pull all of this into Little Feat. And we are ready.

With complete respect to The Doobie Brothers who I’ve been playing with, I do feel an allegiance to them, and they’ve musically given me a gift to play their music and oddly enough to play with them on stuff that we recorded together back in the 1970s. I’d love to see some sort of collaborations between Little Feat and The Doobie Brothers if that’s at all possible. I got to play with Leftover Salmon, with Vince Herman and Drew Emmitt who I adore. They are incredible. Vince and I have a song that we wrote together about New Orleans that I’d love to bring into Little Feat.

If you’re a musician, your opportunity for a platform is through your writing. It’s fine to be influenced or to pay homage. But find your voice and put your voice into where you want to take it. This is an activity that can take us through life. But when Little Feat gets firing on all cylinders, there’s no feeling like that in the world that can compare. It’s not a band; it’s bigger than a band, it’s a life force. People that bring music like this.

It’s been a hell of a ride. 50 years.