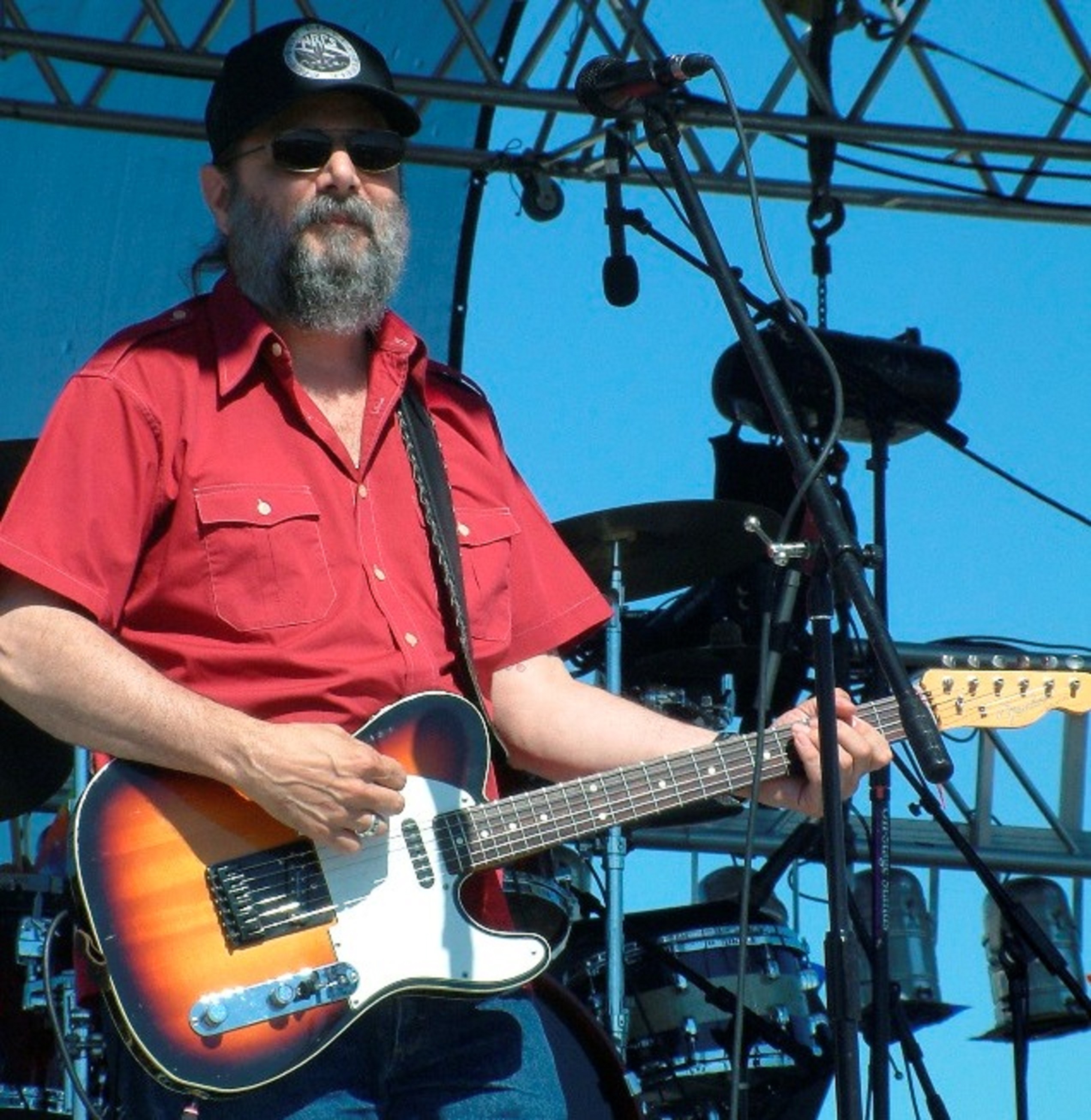

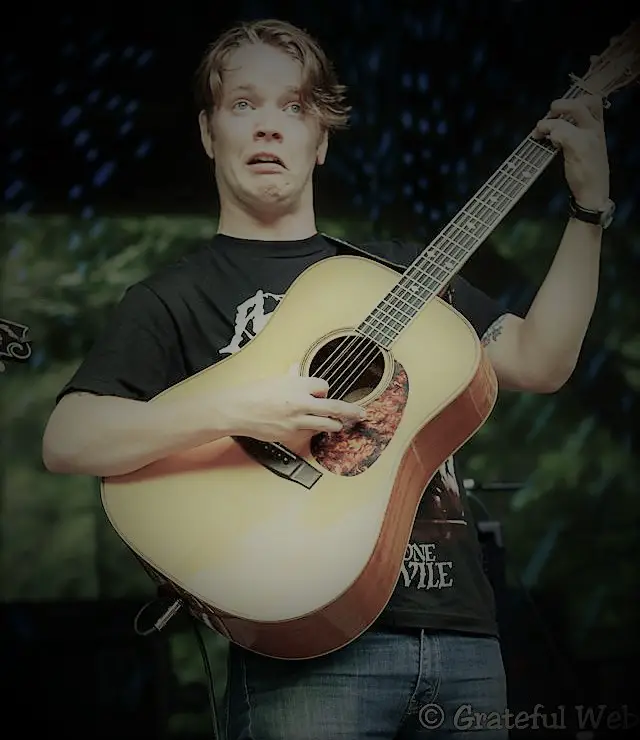

Grateful Web recently had the opportunity to sit down with bluegrass guitar virtuoso Billy Strings. He began putting in his time as a boy, never putting that guitar down or giving up when it got tough. His father and community fostered the bluegrass and folk spirit that runs through his veins. But Billy Strings is not your grandpappy's bluegrass band. The twenty-five-year-old picker titan sat down with Dylan Muhlberg to discuss his evolving songwriting chops, playing with the legends while keeping your cool, and how music is the ultimate bond in these divided times we live.

GW: Wanted to kick things off by mentioning I saw you for the first time in June at the Telluride Bluegrass Festival and was blown away.

BS: Right on. We had a really good time at Telluride. We have a good time everywhere we go but I’m glad you saw that as your first show. We were having fun and I felt like we played well.

GW: It was apparent to me the fiery chemistry between you and your band. Would you mind speaking for a moment about the players and how you’re all connected?

BS: Sure. On banjo Billy Failing has been with me for almost three years. Next to come along was Royal Masat on bass. The crazy thing about us two was that we met for the first time at a Phish concert when Bob Weir [as special guest] came out and played, “Playing In The Band,” and “Miss You.” Just a really incredible show anyhow. Royal and I were both having a good time at the show. He mentioned that he played bass and suggested we jam. And I was down. We got together, and Royal brought in this fellow Jarrod Walker who plays mandolin. We called him up to meet up on the road somewhere and he jumped right in. He’s such a great player. That’s the gang!

We also have a front of house guy, Andy Litle and our tour manager Allie Dale, and our band manager Bill Orner. He’s the guy behind the scenes who’s really cooking this thing.

GW: There’s always so much going on behind the scenes. Even if it’s only been a few years as a unit you can feel that X-factor going on. That ESP.

You’ve been outspoken in other interviews about the influence that your father Terry played on the musician you’ve become. He’s a picker himself. Do you have any early memories or stories you’d care to share about coming up in a musical family and community?

BS: There’s so many. That’s the foundation of who I am. The best part of my life was when I was a little kid. I always look back on that. From the time that I was born until I was about ten or eleven years old my life was basically perfect in my eyes. My dad played guitar and there was always music and parties and people hanging out. Just good times and good people. I was going around, going fishing, getting all grubby with the other kids. And we’d spend time in this place Barkus Park, which is over by this place Muir Glen just outside of where I grew up in Ionia. Barkus was owned by Brad Lasko who inherited it. At Barkus Park they had a campground that used to have bluegrass festivals. Stoney Creek was the one. My dad was best friends with Brad and my mom too. We all would go there all the time. There was always the Salmon Run in the fall. We’d live on the bank of that river, play bluegrass all night long, and catch fish. My parents and everyone would be partying, singing, and playing. And that was the foundation of my childhood, playing “How Mountain Girls Can Love,” around the campfire at Stoney Creek.

My dad and Brad Lasko would pick up a storm. Everyone who was standing around would be singing and smiling. I saw that from the time I was a little kid and that my dad was the life of the party. I noticed that magic he brought even at age five. I wanted to do that. To be like my dad and make people happy like that. Another standout moment I remember was around that same age my dad and I would sit in his bedroom, he’d shut the door, and we’d be sitting around playing all night long in our underwear. My mom would holler up, “he’s gotta go to bed, he’s got school in the morning!” My dad would holler down, “but he’s getting really good in here!” He’d lock the door and made sure I was picking. He was really proud of me every time I’d learn to play a new chord or show him something new. He lit me up with pride and encouraged me so much. He never told me to play like this or that. He did show me how to hold my pick, technique and stuff.

One time we were sitting picking at about six. One of the biggest moments of my entire life still. I remember I was learning the “Beaumont Rag,” which is an old-time tune with a fancy little lick. When I was younger I played strictly rhythm while my dad did all the fancy pickin’. I was learning the chords for [“Beaumont Rag,”] and for some reason when this one part came around I’d mess it up. I kept getting frustrated and I just stopped right in the middle of the song. I said, “Dad, just stop.” I told him he should just play it and I’ll listen. So, then he played the melody and I listened instead of just going to the C chord, counting to four, then going back to the F chord. Instead I actually listened to what he was playing, and what he was saying. I listened to him play the melody, then said, “Okay. Now that I listened to you let’s try again!” And then I nailed it. I really learned by ear and listening to my dad. He just laughed and squeezed my little hand with my pick in it and it was just a really proud moment.

He called my grandmother and I played that song for her over the landline. That was a huge moment for me and really encouraging. My dad is everything to me, he’s my hero and mentor. And to hear him so proud was a big moment. That moment still pushes me today. That’s why I’m doing it today.

GW: It’s beautiful to hear you share your sentiment in those memories.

To shift gears a little bit, you’ve not only developed a huge following rapidly just based on sheer talent but as a songwriter as captured in your album Turmoil and Tinfoil (2017). The songs are topically fascinating and often gritty.

The bluegrass cannon contains gritty subject matter of course; desperate times, loss, sorrow. I’ve also heard you relate some of this grittiness back to your own experiences directly.

Did you ever question if any of that darkness/grittiness would adversely affect your breakthrough album critically or as far as garnering fans?

BS: Honestly, I never thought about any of that at all. The only track I wondered about was, “Spinning,” and that is because that track describes me unspinning my DMT trip. I’m not on a record label and nobodies here to tell me what I can or can’t put on my record. That to me is freedom. I can make honest art. Honest to myself. I don’t have to sugar-coat anything, I can just say what I’ve got to say and that’s why I plan on keeping it independent.

After I put out the album I did get a few phone calls from my friends in the industry. One friend in particular who plays in Greensky Bluegrass called me and said, “man I couldn’t believe you put that on the record. I’m so f&cking proud of you.” I got a few phone calls like that. The crazy thing about that was I just wanted to put that information [from “Spinning”] out there and I wanted to have a spoken word track on the album. Some of my favorite Tom Waits stuff is just like weird sounds and him talking. It’s not even really singing, it just weird noises and him talking about some creepy stuff. To be honest I forgot about the album helping us out and giving us traction. None of that was in my head at all, we were just making the album.

When the album came out, it was like every day something exciting. Rolling Stone covered it. Our publicist was really killing it. I realized then that this album was going to help us out and help us grow. I felt like there was a lot of integrity in being honest with the music and I personally felt it was the best of something we could do. I’m still a pretty young songwriter, and I don’t think I have the knowledge of how to sugar-coat it or make it vaguer. To make it more obscure and not about people that I knew who were addicted to meth. How to make it more of a puzzle. I just said whatever I needed to get out there and it became therapeutic. Some of that stuff on the album was really deep underlying stuff I wanted to get off my chest.

GW: Yeah man. It’s cool to hear you say that the album wasn’t considered as a measure of success. Because we both know the secret to success is having the crowd, the tour, and the love.

A huge part of your life is traveling and playing music. You travel to lots of different areas and meet lots of different folks with different beliefs and backgrounds. Vince Herman of Leftover Salmon once said to me that a concert is the only other place besides church where people gather undivided for one common love.

In these divided times, you believe that musicians have that power to bring people together?

BS: Absolutely. I see it all the time at festivals where I’m in the campground playing music with all sorts of people. And we go to festivals all over like you noted. There are times where we find ourselves in that more old-school bluegrass Christian conservative crowd. I don’t judge anybody for what they think. Not to say I do or don’t agree with you but you’re a human and we can be civil, even if we don’t agree. It’s tough because there is a big divide. A lot of the hippies follow us, and we don’t take kindly to that kind of hate. I’m right there with them. But at a music festival a lot of that is put away. People aren’t at home on their Facebook talking about politics. People came to see the band and the band is rocking and everybody is having a good time, so all the bullsh!t is back behind us.

GW: I hear you. It’s interesting because when I spoke with Country Joe MacDonald, he mentioned that there’s very few topical songwriters/protest songwriters since or now. Had that occurred to you at all?

BS: Yes, it has. Actually, I’ve been working on some material that strikes on that nerve. I’m definitely heading there. I can’t stand that mentality where people would tell me to just shut up and play music. Like, don’t tell us what you’re thinking. And that happens. If I share anything about politics on Facebook I lose a few fans and gain a hundred more. That’s what art is, that’s what folk musicians are supposed to do. I’m on the front lines of the good fight. The only weapons I have are my guitar and my words. That’s the way we fight back baby!

GW: For sure. You’ve taken risks in your life and it’s gained you a lot of adoration.

You’ve graced the stage with other greats like David Grisman, Sam Bush, and Del McCoury, probably folks who are an influence on some level. Do you have any stories of “holy sh!t, I’m playing with so-and-so,” moments?

BS: Man, it happens quite a bit these days and I’ve had to really learn how to just deal with it. Like, me and Del McCoury are friends - get over it. Or, “oh my god I can’t believe Sam Bush just sat in with us at Telluride!” But if I was acting like a crazy fan around those guys they wouldn’t sit in with me. You’ve got to play it cool and act like you belong there. I just sometimes can’t believe where I’m at and that I actually belong here. Having Bryan Sutton and Sam Bush come out and play with us should say something.

There was a string of gigs where I played guitar in David Grisman’s band. He called me and was like, “Hey Billy come play guitar in my band.” I couldn’t f*cking believe it. It was a huge moment to go out and play with Dawg. It’s not just being onstage with him; the shows were the highlights but just hanging around and rehearsing in the hotel rooms and learning with him every single day. When we were driving to gigs we’d only listen to Bill Monroe. Dawg has listened to Bill for over fifty years and has still barely scratched the surface. It’s really cool to see that.

Another proud moment was when back around when I was six or seven years old my dad’s sister Julie bought him a mandolin for his birthday and he was really getting into those old Dawg records at the time. One time I was playing with my toy cars when my dad yelled at me from across the house to come to him, I thought, “what the hell, and I in trouble?” But when I got there he told me to sit down. He grabbed this record “Doc and Dawg.” - I was already familiar with Doc Watson but at that moment he said, “Son, this is David Grisman, you need to know him. This is one serious cat here. You need to make sure you play attention to his playing.” And he sat me down and played “Doc and Dawg."

Fast forward to when I was twenty or twenty-one. Don Julin and I were opening for Doc and Dawg. I called my folks and got my mom and dad on the guest list. When I told him to come down to Columbus because we were playing with Doc and Dawg he came right away. When my parents got there, I was able to walk my mom and dad into the greenroom where Doc and Dawg were. My dad introduced me to David Grisman’s music as a kid and all those years later I was able to literally introduce my dad to David Grisman. That was really awesome. He was geeking out. They were hanging out and having a good time. Next, they got their guitars out and my dad, David Grisman, and Del McCoury all sat there and played for a little while. We were singing songs with three-part harmonies with me, my dad, and Del McCoury. It was so frickin’ awesome. How proud does that make him and how proud does that make me to be able to introduce my dad to one of his heroes.

Then flash-forward again to two weeks ago at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville when my dad came down again for Del McCoury Band. And Del invited my dad out onstage to play with the band and me. With his son, an idol, onstage at The Ryman, singing The Stanley Brothers. Another proud moment.

GW: Indeed. What a story. Terry must be so proud of you.

I wanted to ask a final question surrounding your non-bluegrass influences or tastes. In regard to your style, you’ve got some nuances which indicate influences outside of traditional bluegrass. Who are some contemporary musicians that are inspiring to you outside of the bluegrass canon?

BS: Les Claypool. And I listen to Cryptopsy, this Canadian death-metal band. But man, I do really like Primus. The Grateful Dead of course, but that’s sort of in that folk vein. A lot of Wood Brothers, Tedeschi Trucks, I like Marcus King’s guitar a lot. I still just listen to a lot of bluegrass, old-school bluegrass and old-school Doc Watson. My interests have never expired there. It’s the best sounding stuff. I love the Bill Monroe anthology album. Outside of that, Pearl Jam, I really like all their albums but “Yield,” was a really cool album, which reminds me of growing up. Three more really big ones are Johnny Winter, Black Sabbath, and Jimi Hendrix.

GW: All legendary artists indeed, in good company.

You can catch Billy Strings on the road all over the U.S. into the fall and beyond.