Parchman Prison is in the Mississippi Delta and is notorious for brutal conditions and a very high black population. In 1996, the historian David Oshinsky said, "Throughout the American South, Parchman Farm is synonymous with punishment and brutality. It's the closest thing to slavery that survived the Civil War." Ta-Nehisi Coates quoted Oshinsky's writing in his 2014 Atlantic article, "The Case for Reparations." The prison was founded in 1901, on a former plantation site.

In 2020, Jay-Z and other entertainers filed two lawsuits on behalf of inmates, alleging poor living conditions. At that point, state health inspectors had already found repeated problems with broken toilets and moldy showers. Inmates said some cell doors did not lock, and it was common to see rats and roaches. The lawsuits were dismissed earlier this year after the inmates' attorneys and the state Department of Corrections said improvements had been made during the past three years, including installing air conditioning in most of the prison, renovating some bathrooms and updating the electrical, water and sewer systems.

Nevertheless, conditions still are poor. In April of this year, the U.S. Justice Department issued a report that said Parchman had violated inmates’ constitutional rights. The department said the prison failed to protect inmates from violence, meet their mental health needs or take adequate steps for suicide prevention, and that the prison had relied too much on prolonged solitary confinement. The state Department of Corrections have said for years that it is difficult to find people to work as guards because of low pay, long hours and dangerous conditions. The Justice Department said last year that it found “gross understaffing” and “uncontrolled gang activity.” It also found that insufficient security gave inmates “unfettered access to contraband.”

The prison is the subject of a number of blues songs, most notably "Parchman Farm Blues" by Bukka White and Mose Allison's "Parchman Farm." Bessie Smith died in the nearby town, Ike Turner and Sam Cooke were born in the neighboring town, Robert Johnson reportedly sold his soul at the crossroads there, Muddy Waters was raised nearby, and the murder of Emmett Till is barely a half-hour drive away. Son House and Elvis Presley's father was jailed there.

The prison also served as a major source of material for folklorists such as Alan and John Lomax, who visited numerous times to record work songs, field hollers, blues, and interviews with prisoners. The Lomaxes in part focused on Parchman at that time because it offered a particular closed society shut off from the outside world. On a Sunday morning in February 2023, Grammy-winning music producer Ian Brennan went to Mississippi to record with some prisoners for a few hours. The result is an extraordinarily powerful and honest recording. We spoke with Brennan recently to discuss the album, and his work, in greater detail.

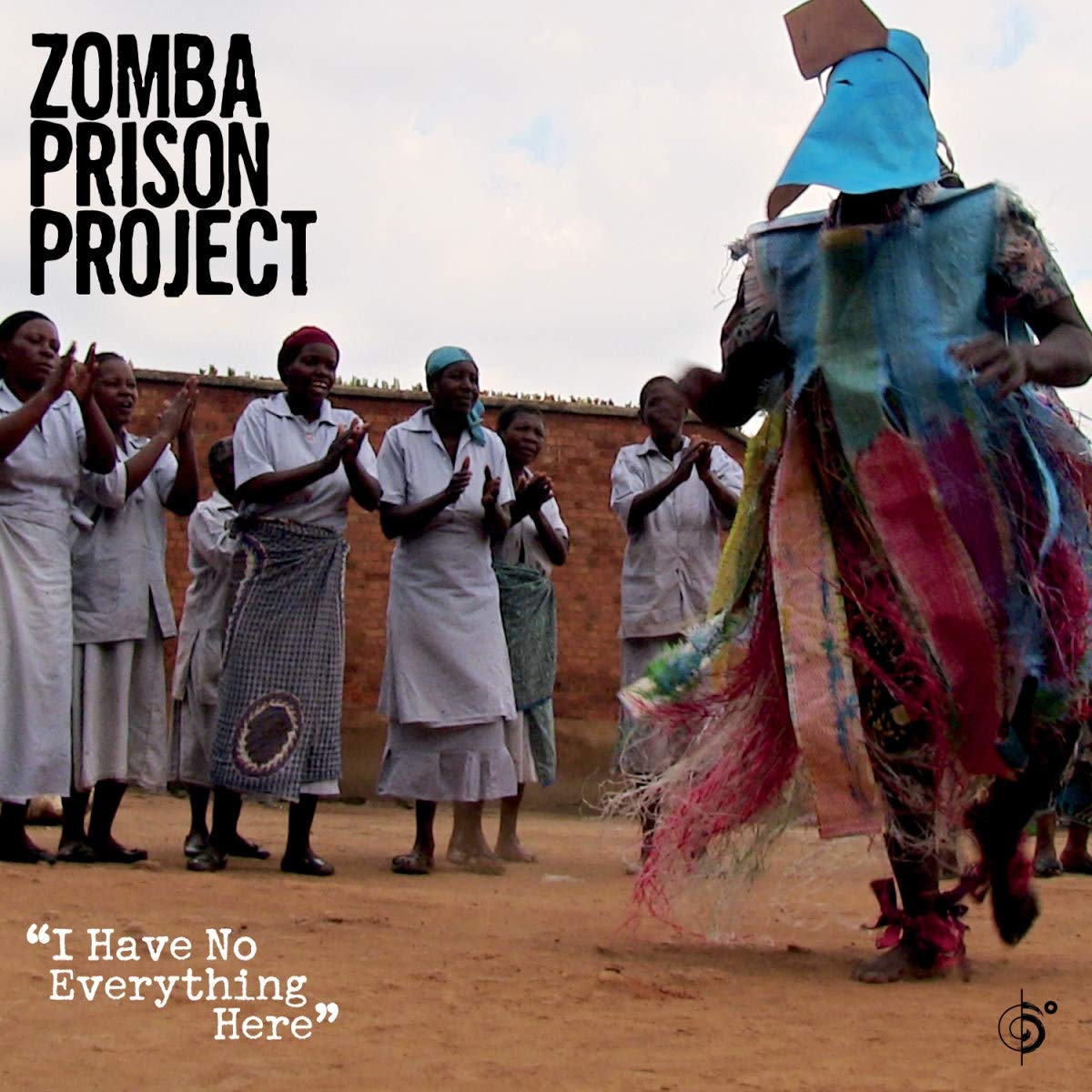

GW: Is there an album you've produced or a song from one of your albums that you're most proud of working on? For me, the Zomba Prison Project was most affecting, in particular "Please, Don't Kill My Child" and "I Will Never Stop Grieving for You, My Wife."

Ian: Yes, those two songs were both really special. In general, the projects where we have had the longest relationships—like with The Good Ones (Rwanda) since 2009 or the Malawi Mouse Boys since 2011, have been especially moving. But virtually every project has brought some spin-chillingly intimate moments when people bare their souls.

GW: How do you stay hopeful about the state of music in these times? I often find myself feeling cynical, as the amount of labels has declined, and (as you mention in your first music book) so many modern recordings are poorly mastered and overly compressed. On top of that, the countries you make your records in continue to be marginalized and overlooked. How do you still find hope?

Ian: It can be dismaying. But I think it is important to always remind ourselves that we are in the midst, not at the end of history. And most people on the planet proportionately have good intentions—otherwise, we wouldn’t have made it this far collectively.

GW: That's a really interesting reframe. What do you hope happens to the music industry in the future?

Ian: I have little hope for the music as an industry. It continues on a decades-long trajectory of ever-greater consolidation, corporatization, and concentration of power. But I hope in response that more people will return to music-making, not for performance's sake, but just for their own private enjoyment.

GW: You've mentioned that music is medicinal. What that means, essentially, is that to strip away the nutritional content of music is to cut off a sense of nourishment. And yet the corporate music industry often does just that, giving us processed-sounding music. What do you think are the emotional and societal consequences of this?

Ian: I think we see it in how performative many people’s actions are—even in how they parent. Social media and video phones have only exacerbated this crisis where people are motivated by image and external, rather than intrinsic, reward.

GW: Getting to your latest release, Parchman Prison Prayer, I listened to Alan Lomax's recordings at Parchman before listening to this record, and I was amazed by how cohesive your recordings are with his, despite seventy-five years of separation between the two projects. What do you think it is about gospel music that makes it so timeless?

Ian: For many of the men in Mississippi, Gospel music is the throughline. Many listen to Rap predominantly now and Blues is all but forgotten, but Gospel is something that has been a lifelong presence for many—especially those from the rural areas and they are the majority of the people on the album.

GW: The pushback people sometimes have with projects like this is that criminals are being glorified. But as you've noted, the real point of this work is to humanize people. I'm wondering if you could talk a little more about that.

Ian: The USA incarcerates more people than anywhere on earth. Currently, over two million citizens are behind bars, and African Americans are imprisoned at at least three times the rate of Caucasians. Denial of another person’s freedom is something that no person or corporation should ever be allowed to profit from. We have to ask ourselves at what point does detainment stop being constructive to the whole and start being destructive. These individuals remain a part of our communities and we should want them to return healthier, not more damaged, than before being sentenced.

GW: When you're recording something, can you tell what's going to make the final cut, or does your perception sometimes change later when you're putting the albums together?

Ian: My perception is often wrong. Recording has its own alchemy—what sounds good in a room might not render well when played back later and vice-versa. But there are moments when you just know something magical has occurred. And that happened repeatedly when recording with the men at Parchman Prison.

GW: Your approach to music is very minimal in many ways, carefully avoiding the dozens of takes and overproduction that is the standard in the music industry today. It's one of the things I love about your work, in projects as disparate as Bob Forrest's "Survival Songs" and Ustad Saami's albums. On the other hand, it sounds like you're a lot more exacting in your writing (I read that you spent about a quarter-century revising "Sister Maple Syrup Eyes"). Can you talk a little bit about that dichotomy? I'm fascinated by the difference in your approach to those two mediums.

Ian: Music, performance, and film all have a corporeal element that the written word does not. I have always adhered to the concept that “writing is re-writing."

GW: In addition to plugging this album, I'm wondering if there's any books or movies, or albums you've encountered recently that you'd like to give a shout out to? Particularly interested in any that might be under the radar.

Ian: I think that the 2021 Finnish film The Blind Man Who Did Not Want to See Titanic is one of the strongest and most important pieces of cinema ever made. It is a landmark in disability representation, but also as taut a movie as can be. And I would encourage everyone to read the poems of Raymond Antrobus. He is one of the most gifted poets of his generation.