Something really remarkable happened at the Fare Thee Well shows in 2015. Instead of being a goodbye, it was a re-ignition, a passing of the torch in some ways. Although Jerry was always quick to point out that it was Dead Heads who created themselves, the phenomenon of Dead Head-ism was focused on the band for the first 30 years. And it was fairly fractured for the next twenty, with some liking some iterations, and others, not. And the musicians aren’t done, whether it’s Dead & Co. or Phil and Bobby’s recent duo, or the future outings of Billy and Mickey.

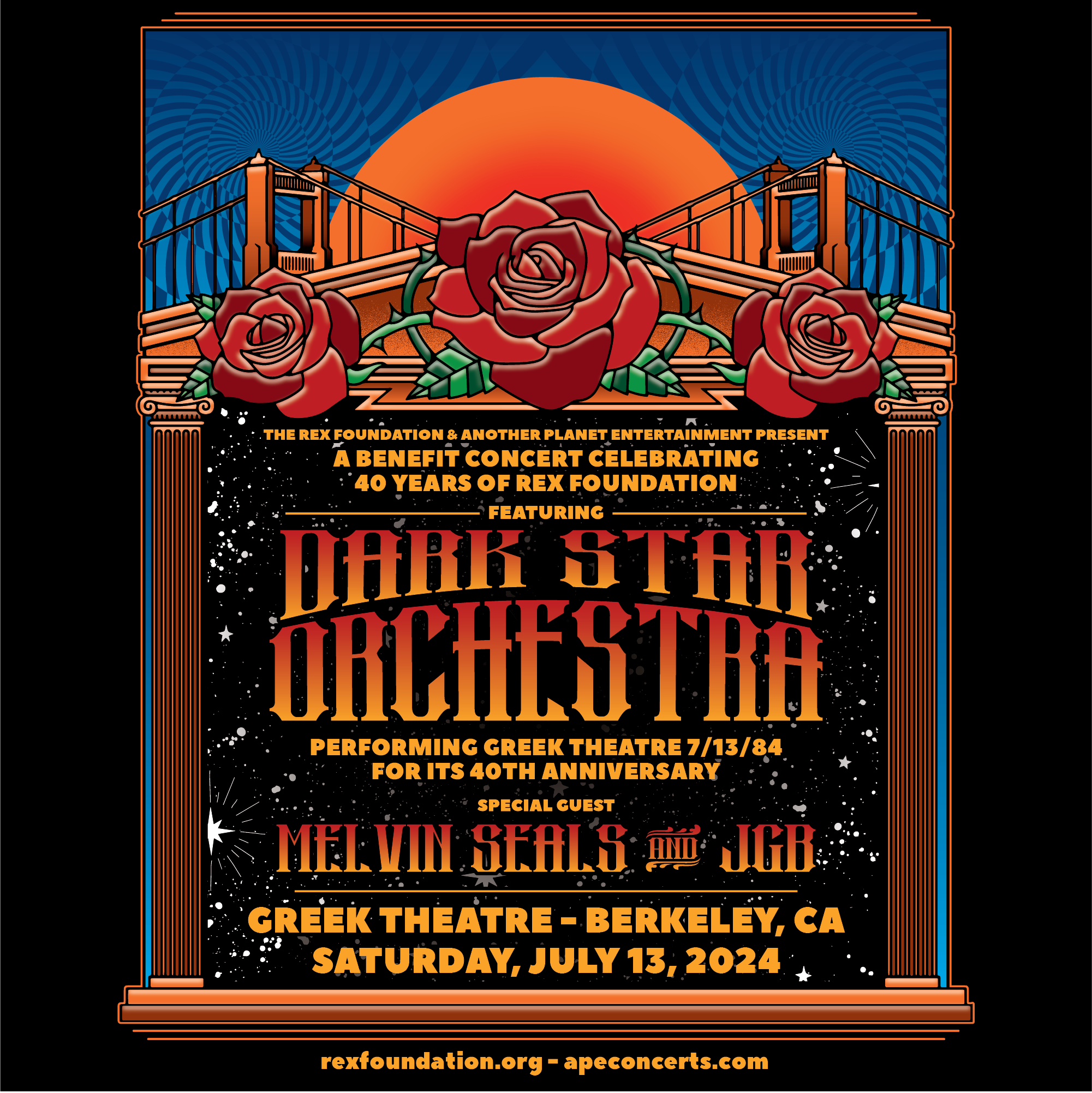

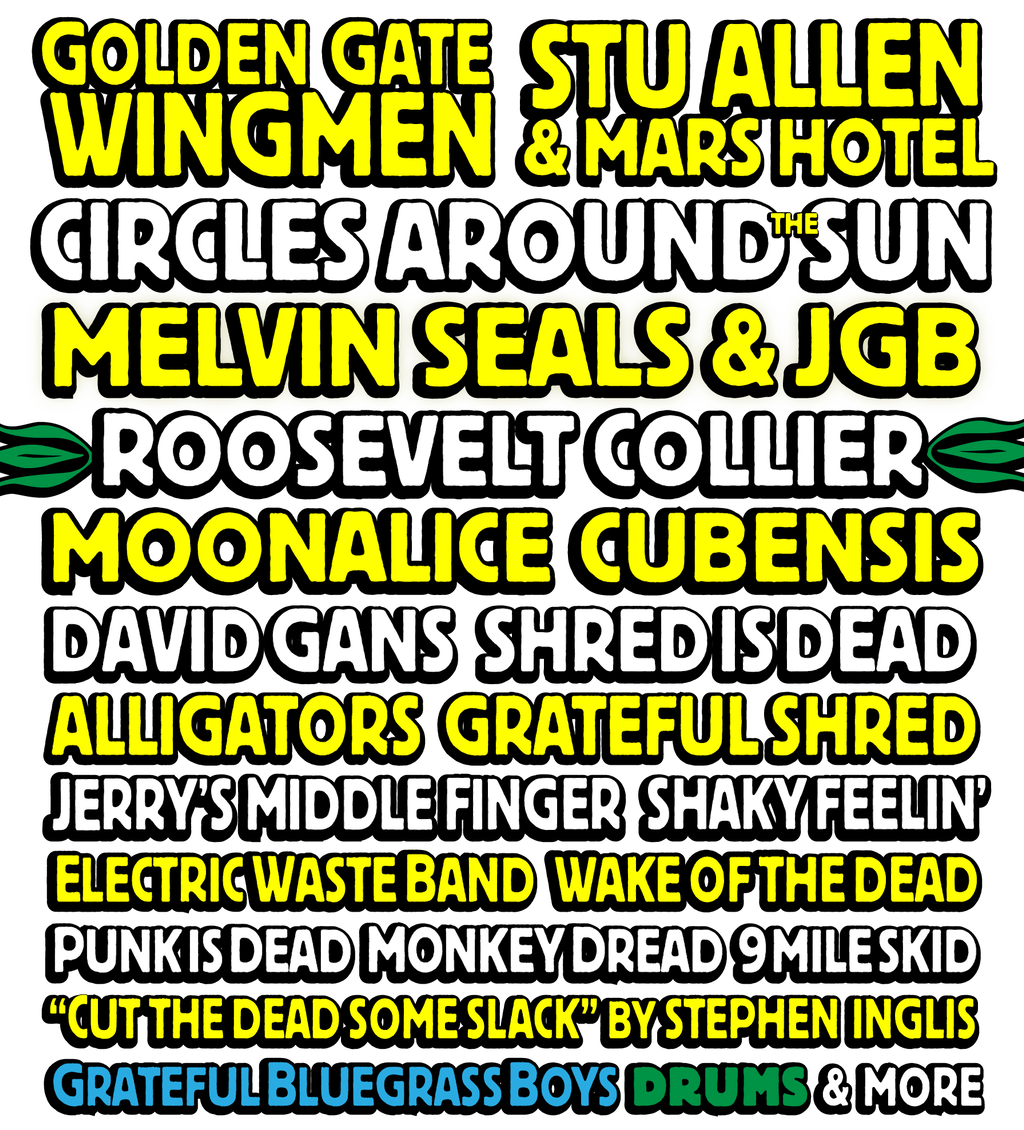

But it’s fairly evident that the energy of Dead Heads, instead of dying away as, to be honest, I had sadly expected, is growing. The locus is not the band but the music, which has become a stand-alone genre that is played coast-to-coast. Which is the rationale for the Skull and Roses Festival, April 6 through 8, Ventura County Fairgrounds. There will be musicians you know—Golden Gate Wingmen (John Kadlicek, Jeff Chimenti, Jay Lane, Reed Mathis), Stu Allen and Mars Hotel, Melvin Seals and JGB, Circles Around the Sun (Neal Casal, Adam MacDougall, Dan Horne, Mark Levy), Cubensis, David Gans—and those whom you likely have not—Roosevelt Collier, Punk is Dead, Shred is Dead, Stephen Inglis, Nine Mile Skid.

There’ll be drum circles and a tasty Shakedown Street and, what the hell, the Pacific Ocean thrown in. The promoter is a Dead Head and has one agenda; to keep the scene thriving and growing. Tickets are modestly priced, there’s camping in the parking lot the same way it was in the 1980s, and a seriously good time is on the horizon. Go to www.skullandrosesfestival.com for tickets.

Marcus Rezak is the lead guitarist of Shred is Dead. The band was so warmly received at the first Skull and Roses they were invited back.

I first picked up the guitar when I was ten years old, actually. I found it in my mom’s closet. I started playing and fell in love right away; there was just something about it, it got my interest going. I was self-taught for the first few years, just listening to music and getting guitar magazines, stuff like that. And I hung out with friends who played, which was a big inspiration. Then I started getting lessons from a few great teachers. Around the age of 14, I discovered a teacher who was really into the Dead and improvising by the name of Jon Gram5, that whole concept was new to me at that point, and he got me going in that world.

In high school (Highland Park), I was into alternative rock, ‘60s rock, Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa, Rolling Stones, the Beatles – pretty much psychedelic rock bands. And of course the Dead was something I was getting more and more into, too. I got into the jazz band in high school, and that got my mind going in another direction. In between classes, I’d be in the courtyard playing Dead songs on acoustic guitar, escaping the mundaneness of school. I started reading music in the jazz band, but credit my advancement to my guitar teacher at the time, Aaron Weistrop. I had double knee surgery when I was 17, and while recovering, I intensively self-taught myself music theory via books, and got into Berklee School of Music in Boston. Spent four years there, had some amazing teachers, hung out with some incredible players, other students, and graduated in 2006 cum laude.

I primarily studied jazz at Berklee, but I was also playing a lot of funk with people, jazz influence on top of rock, fusion, more avant-garde music styles rather than anything pop or mainstream. I was just working hard to get myself better as a player.

Even before I graduated, I knew I wanted to be on the road performing. My band ended up on a bill with another band that happened to be from Chicago, 56 Hope Road, and we hit it off, and they wanted me to join them as soon as I finished school. So I had that lined up, and ended up playing like 150 shows a year like right off the bat. They actually won some jam band “most shows in a year” award. I really cut my teeth with them. I got to take everything I’d learned and apply it on a nightly basis in a crowd setting. The other musicians in the band really helped push me, especially the drummer, Greg Fundis, who I still play with today, different projects. He’s in a huge Led Zeppelin tribute band, called Led Zeppelin II.

After a couple of years touring, I decided to start my own group in Chicago with three other musicians, all of whom also went to Berklee. We were called The Hue. We were like an instrumental progressive rock jam group, kind of – we had a lot of influences from heavy metal to jazz to all kinds of stuff. We did a bunch of stuff with Umphrey’s McGee, after shows, and they sat in with us, that was the kind of people we were looking up to back then, and the people I now play with. We had two albums, Unscene and Beyond Words, and yeah, that group did some great music together from 2008 to 2012.

Toward the end of that group, a band called Digital Tape Machine got started. And that band was based out of Chicago with members of Umphrey’s McGee, primarily Joel Cummins on keyboards and Kris Myers on drums. And we originally planned on it as a studio project, but the music was great and people were really interested, so we decided to take it out on a live basis. DTM played for about five years, consistently doing big festivals like Electric Forest, All Good, Summer Camp, Bear Creek, and more. We recorded two albums, Be Here Now and Omens. It was electronic-based, so it was performed as a band plus electronic production. We played a lot of great shows together—you never know, we might play again. But during that time, I also (laughter) went and did a master’s degree in jazz at DePaul University—luckily, they were really flexible about my schedule. Had a great time there, Bob Lark and Bob Palmierei were particularly great teachers there.

And that takes us up to pretty much the last couple of years, where I’ve been more doing my own projects. I started a group with Arthur Barrow called Cosmic Playground—Arthur was Frank Zappa’s bassist for many years, he was on Joe’s Garage and You Can’t Do That On TV and Tinsel Town Rebellion and a bunch of others. That’s been really fun, doing Frank Zappa shows with him and several other of the former members – Chad Wackerman on drums, and Robert Martin on keys and saxophone and vocals. So I got to play the Frank Zappa role with those guys and had fun learning from them. Arthur’s been very key in taking me under his wing and showing me how Frank taught him and how they worked together, and that’s been an invaluable experience. Playing live between Arthur and Chad, I’ve felt like I was doing justice to Frank Zappa...

There’s been other side projects, but the main thing I’ve been focusing on, other than my debut album of original music coming out this year, is Shred is Dead. My first exposure to the Dead was a hat with the Rosebud logo on it—I was like 13 at a summer camp—and I asked about it and the guy said it was from the Grateful Dead, “You never heard of the Grateful Dead,” and I said, “No.” He had a bunch of tapes, so he turned me on to what they meant. I got into it, and soon after I got pulled in by, I’m pretty sure, “Scarlet-Fire” from Cornell. My uncle was a great Dead Head back in the day, and he used to play guitar for me when I was a little kid, I don’t even remember it, but I saw pictures. So that was my first experience.

And then all through high school, I listened to a lot of Dead, Howard Wales and Jerry Garcia, different stuff than just pure Dead. I’ve always had that influence— playing free and open. I wanted to get back to that, after playing a lot of really constructed music, really arranged. And then Fare Thee Well came to Chicago, and the whole town was excited, the vibes were amazing. And I had a vision of doing a pre-show for that whole weekend on Thursday night. So I booked a show at the Emporium in Wicker Park, Chicago, and got a bunch of my musician friends to come down and play the show.

It wasn’t called Shred is Dead but it was based around doing the Dead’s music in a progressive jazz, fusion-y and electronic at times way, different from the way anyone else was doing it, in a non-traditional way. And it went really, really well. Fareed Haque (Garage Mahal) was playing guitar also, Todd Stoops (Raq, Electric Beethoven), Steve Molitz who played with Phil & Friends, Greg Fundis was on drums, and Joel Cummins from Umphrey’s McGee came down too. So it was a really great night, and the vibes were really high. And it kinda got me thinking. I really loved playing the music, and I wanted to do more of it.

I started thinking about how to make it happen—I started taking a look at the arrangements and the songs that I really loved, and started putting a band together. The next ones after that were a few shows on the East Coast, I can’t remember what we were calling it, maybe Without a Net. Reed Mathis was on some of those.

Then I decided to make it an actual group, made arrangements and rehearsed people, and named it Shred is Dead, and the first show we did was at Skull and Roses last year. We’ve done a bunch of shows since then. We opened for Melvin Seals & JGB in L.A., and in a couple of places in Chicago, with Jay Lane in Denver, did one with Cubensis at the Lighthouse, and we have some more coming up in Denver at Be On Keys April 2 and 27. Oregon. And then Skull and Roses, where we’ll have the Grammy-winning Cuban percussionist Raul Pineda (a Chucho Valdés associate) performing with us. And I’ve got plans for an album that’ll be Shred is Dead emulating the Dead in a way that’s different. It’s been really fun to brainstorm on, see how to make the music different.

Ventura’s super-vibey to play in. You know—palm trees and blue skies, it’s just a great place. There’s a nostalgia factor, which I love.

Marcus also shared some links:

Full Show - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p4_gXNg52D0

Estimated Prophet ( Dub Style ) - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IlNAD_Fxopw

Row Jimmy- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2OGOMdtFUp8

https://archive.org/details/ShredIsDead2017-12-01.AKG.P170.AUD

Roger McNamee sings and plays rhythm guitar and bass in Moonalice. He is an activist on the subject of the threats to democracy and public health in social media, a strong supporter of poster artists and the founder of the Haight Street Art Center.

I first became aware of the Grateful Dead I think in 1968, when I was about 12, when my older brothers – I had an older brother 12 years older, and one ten years older, both hugely into the Dead, and I really worshiped my brothers. The Dead played the RPI Field House (I grew up in Albany) sometime in the late ‘60s, and my brothers went to the show. One of them was out of college and had seen the Dead numerous times in New York City, the other one had seen them both in New York, and I think maybe New Haven. But they played locally, and that’s when they came onto my radar.

So in 1971, I changed schools, and there was a kid at the new school who had a reel-to-reel tape deck, which his parents had just given him. I didn’t have any money, I didn’t have any stereo stuff. But he had it, and he had just recorded American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead on it, because they were brand-new albums. And he played them every single day, and I saw him a lot, and I just heard those albums over and over, and I completely fell in love. And he also had a poster that was a Kelly and Mouse poster on his wall, and I fell in love with the art, too.

Before this, in 1969 my brothers went to Woodstock and they came back and they were just going crazy. So I’m growing up in this environment and it’s just a rite of passage to go on tour. For me, the breakthrough came in the summer of 1973. In the spring of 1973 I read in Rolling Stone or the Village Voice that there’s going to be this festival at Watkins Glen Racetrack, “Summer Jam.” It’s going to have the Allman Brothers, who I’d already seen a couple of times, it’s going to have the Band, and it’s going to have the Dead. For all intents and purposes, these are my three favorite touring bands of that era, although I’d only seen the Allmans.

The tickets were $10.50, and for me, that was a huge amount of money. I went and stood in line at Ticketron, which was inside the Macy’s at the mall where I grew up. I got a ticket, and I persuaded my best friend to go, and my mother said, “You can’t go to this thing, not unless you get some mature person to go.” So I talked to my older brother Dan, and he said, “I’m all in. My girl friend and I will drive you; we’ll all go to the show.”

We get in their car, and we’re getting on to the New York State Thruway at Albany and the hood blows up and comes off of one of its hinges, and we haven’t even left town yet. So we find a piece of rope, tie the fucker back down, and get on the Thruway and head west. My brother knows this guy who lives really near Watkins Glen, so instead of going and camping out, which would have been better because we would have gotten the Soundcheck, we stay in the barn of this guy who lives right near. And we drive up the next morning, and the traffic jam is over. We’re coming from the other side, we literally park the car at the gate. We probably walked 50 feet before we handed in our ticket. We were probably the last people to hand in their tickets because pretty soon everybody’s getting in for free.

So I get in there, and we get perfectly situated between the speakers, next to a plastic tarp covering a bunch of plastic bottles of water. We brought some entertainment products, in my case shall we say a member of the larger Grateful Dead family, and it was one of those days, I’m 17 years old, they come out and start with “Bertha,” and I have in head in this altered state that every song is going to be “Sugar Magnolia.” I go back and look at the set list and it was in many ways the greatest set list of any show I ever saw. They played forever. It was the proto-Wall of Sound, and it was complete magic. Then the rain comes and fortunately we have the tarp next to us so we’re able to stay sort of dry, and it goes away, the Band finishes.

My one encounter with Jerry: 1975, I’m a sophomore in college, Jerry Garcia Band comes to Woolsey Hall in New Haven. I’m working on the school newspaper, and I’m going to cover the show and interview Jerry. It’s with Nicky Hopkins. And Nicky is shall we say not at his best. They practically carried him onstage for the sound check. Sound check runs way long, and they have hardly any time for dinner. Big Steve and Jerry come out, I’m the only one out there, and Big Steve goes, “I’m really sorry, but there’s no time to do an interview. But here’s Jerry Garcia.” Jerry goes, “Hey.” I go, “Hey.” That was my entire conversation…

I moved to San Francisco, and I was there from ’76 through ‘78. It was a time when my girlfriend decided that the thing she was going to deprive me of was everything I loved, starting with the Grateful Dead. So I miss all those shows…

I finally go back to college, and I have a new rule: I’m never going to go out with another woman who will not love the Grateful Dead, baseball, and skiing. So I meet this woman who was a grad student getting a Ph.D. in music. And I invite her to our first date, to go see the Jerry Garcia Band at the University of New Haven gym. We might as well check off one box right away. She’s getting a Ph.D. in music theory and her first reaction is, “What instrument does Mr. Garcia play?” She’d missed a lot of stuff. We had a ball. We go to 10 shows on the spring tour out of a possible 14, so we check that box off. We go to a baseball game and in the third inning I go to the bathroom and she scores balls and strikes while I’m gone, and I go, “’I’ll teach the woman how to ski,’ and we’ve been married ever since.” (laughter). Thirty-eight years and we celebrate that Jerry Garcia Band show every year.

In 1998 I get the call about Terrapin Station (the original concept was a Dead museum/playground/performance site). I said to the guy that I wouldn’t talk with him unless Peter McQuaid (then President of Grateful Dead Productions) or a member of the band calls and tells me it’s something they care about. They have strong feelings about outsiders and I’m a front of house Dead Head, I’ve never been backstage. An hour later, Peter called, and I said “Why me, I don’t know anything about real estate,” and he said, “You’re a Dead Head and you know about investing, and we don’t have a lot of Dead Heads who know about that.” OK, I’ll take some meetings.

This was the first time I started to meet members of the band. We went to this thing at Bel Marin Keys. It’s me and Peter on chairs, and Parish and Ram Rod in the front row. There were probably about 40 people there. And they’re trying to decide if I’m OK. “How do we know you’re really a Dead Head.” “I’ve been to a couple hundred shows.” “Lots of people do that.” “Well, how many of you guys were in Telluride when Jerry had to do the restart of “Brokedown Palace”?” And only about a quarter of the people there had been there. “How many of you were there in Hartford in ’86 when Phil did the “Earthquake Space”?”...Parish and Ram Rod came up to me afterward and they almost patted me on the head and said, “Son, I think you’re going to be OK.”

So I spent three years working on stuff like that with the Dead and had this life-changing experience of being a Dead Head who got to meet and interact with the band, got to be a board member of the Rex Foundation, an opportunity to help out, like with the Archives.

The notion that you can have a whole festival like Skull and Roses dedicated to these things—you know the music will be great, but even more importantly, it’s the scene.

We (Moonalice) just played three shows in L.A. with Cubensis. Our band was put together to be original music for Dead Heads, music that Dead Heads would like. On this run, we played one venue for the 19th time with Cubensis. The place was packed to the rafters. I’ve been on a mission to make the world aware of the dangers of social media, and that’s been draining—so to be back on stage with my tribe, it was like going from Kansas to Oz (from sepia to Technicolor).

What always amazed me was the diversity of Dead Heads. I mean the crunchy Granola thing has always been there, but the scene is open to everyone. You could bring to the show whatever you brought, but when you were there, you were part of the family. The diversity was part of what made it work.

David Gans was a Bay Area player and music journalist who became nationally known as the host of the “Grateful Dead Hour” radio show. He tours regularly as a solo artist and has sat in with almost everybody.

I have been a musician since I was a child. I started playing the guitar when I was 15, and I was already into a trajectory of writing my own music, following musicians like Elton John and Cat Stevens, when I got turned on to the Grateful Dead in 1972.

I was living with a high school buddy, and we were writing songs together. He’d been trying to persuade me to go see the Grateful Dead for a couple of years. And I didn’t think I was going to be interested in it because I looked at their record covers and I saw that they had a song called “Ripple” and I thought it was a song about cheap wine. Then they had a song called “Cumberland Blues,” and I wasn’t that into the blues and they had a song called “New Speedway Boogie” and I really thought that boogie was the least interesting kind of music there was so I didn’t think I was going to like it.

So I took what turned out to be a gigantic dose of LSD and rode up to San Francisco with my buddy and climbed up into the last row of Winterland – we got there really late, so it was already underway, and there were no seats. We wound up literally in the last row, and it must have been 120 degrees, the place was packed. And I was just blazing on this huge amount of acid, so it all just went by in a roar.

But little bits of it stuck to my mind, so when I got home, I started listening to the records and picking out the things that I’d heard. It turned out that it was “Bertha,” it was “Black Throated Wind, it was Bob’s guitar on “Greatest Story Every Told,” little things kind of etched themselves in my mind, and when I went and heard the songs they came from, I got really interested and excited. It turned out that their music was much more interesting than I thought it was going to be, and much more along the lines of what I was doing – really amazing songwriting.

Which really just showed me that looking to write a hit single was not the path for me, that this kind of songwriting was much more interesting and rewarding. And then over the years I started understanding what they were doing in between the songs, too. So within a couple of years I was pretty deeply into this, and that coincided with the beginning of my journalism career. So when I was writing for music magazines, I started writing about the Grateful Dead, too. And that led me to being introduced to them and interviewing them and stuff like that. It really was the insistence of my collaborator that I go check it out and the strength of the acid (laughter)…and just the fact that there was this incredible charisma coming off the stage, too. Even from that distance I could tell something amazing was happening.

So when they came back in August (1972) we waited on line overnight to buy tickets at the San Jose box office, and we went to Berkeley Community Theatre for four shows in five days and we just got to watch them play, to be in that room with that incredible communal vibe, and be in that place where the thing was happening that was so deeply affecting people, and the commitment of the guys on stage, and the power of the songs -- “Tennessee Jed,” and the thing about it was that there was this space between the notes, and I got to watch Bob and Jerry interacting, the way their guitars intertwined, it expanded my awareness of what guitar playing was, too.

So really the Grateful Dead just kicked open this entire wide universe of stuff, and I started listening to the songs, where they got them – between the G.D. and Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen, I got interested in country music -- and it just took care of itself from then on. I didn’t even start figuring out the community part of it for several years after that – I went with my buddy. I moved to Berkeley in ’74 and started playing Dead music with some guys up there, and that expanded my consciousness of what it was about. It really was that 1972 stuff that made a lifer out of me.

The GD Hour began in the fall of 1984 when Dave Marshall at KFOG started a set of specialty shows every night at 10 – there was a reggae show, a new-age show, and one of them was the Dead Head Hour, with M. Dung as the host. And he started relying on a few local guys, like (the late) Paul Grushkin, Richard Raffel, and I to help him by providing material. Dung was seriously overworked – he had the morning drive show, too, getting up at 3 a.m., plus he had the Sunday night Idiot Show. So he really welcomed the help.

And I got really really into it – I was dating another KFOG DJ at the time – so I was spending time at the station. So I started helping him produce pieces of the show. Then I appeared on the show in February of 1985 to promote my book, Playing in the Band, and I produced a little documentary called “Greatest Pump Song ever wrote,” because I had stories from Hunter, Weir, and Mickey about the making of “Pump Song,” which became “Greatest Story.” So the station was happy to have me involved, and I was enjoying the hell out of doing it, and over the course of 1986, they asked me to take over responsibility for the show. And Dung boy was glad to see it happen, because he was so overworked.

So I wound up being given sole responsibility for it, and again, without making any plans whatsoever, the show took off nationally. I got a call from WHCN in Hartford, Connecticut, asking if they could carry the show. A classic rock station in San Diego asked if they could carry it. And the coup de grace was when WNEW-FM (New York City) asked if they could carry the show. And I went ‘Oh my God, this could really be something.’ So I called Jon McIntire and asked him for his advice, and he said, “Seems like a good idea, let’s take it to the band.’

And so I went to the band and laid out the case for it, and everybody said fine. Phil in particular was in my corner, he said ‘You know the music, go for it,’ and they gave me access to the vault. So I, without ever intending to, became a radio producer. It led to a year in commercial syndication, which did not go particularly well, and after that I took back control and started working with public radio. And it’s been half my day job ever since. None of it was planned, but very much in the Grateful Dead tradition I followed inspiration and instinct into a variant. [hard to hear that word.]

When I started touring, I couldn’t afford to take a band on the road, so I went as a solo act. It was a lot of fun, but it was a very limited format for a guy who wanted to be jamming on stage. I bought a looping device, which enabled me to play a lot more guitar in a solo setting, and once I had that pedal on the floor, I started getting ideas.

But the other nice thing about my current traveling life is that I get to hook up with lots of musicians as I go around the country I really feel like a spiritual and musical child of the Grateful Dead, not so much in the specifics of the vocabulary but in the approach to making music. There’s a continuum between improvised music and composed music and spending time in that world between composition and improvisation is deeply rewarding.

Another part of the continuum is between what I call the dogma playing and the interpretation playing. Dark Star Orchestra being the absolute best of dogma playing, where they replicate the Grateful Dead’s approach brilliantly and faithfully, and they’ve got that end of things nailed down. It’s not anything that I would want to do – I prefer to be over at the other end of interpretation, but again, where people sit along the lines between the two is great, and it makes for –- the idea of a whole convention of people playing Grateful Dead music isn’t nearly as boring as you might think if you don’t know this stuff. It really is a great way to look at it, a myriad of different approaches to it, rather than a bunch of people all enacting the same thing.

I think Fare Thee Well caused it all to gel, and gave a lot of people the opportunity to realize, “Look at this! There really are tons of us still.” I run into a lot of people bringing their kids to shows. One of the remarkable things about my musical travels is that I’m playing with young musicians who weren’t born or were in diapers when Jerry died, and they’re deeply into the music.

I remember when Blair and I interviewed Jerry in ’81, and I said to Jerry, “I think this music is immortal and will outlive the men who made it.” Blair sort of cringed a little bit but… it turned out to be right, and it’s the songs. God, I hope Hunter knows how this is going. The songs are going to be played and sung more now than ever. Every town I go to has Grateful Dead musicians in it, and good ones, too. The sheer number of musicians who are keeping these songs moving forward is a wonderful thing, and it’s a testament to the power of it, and to the accuracy of our observations back in the day!

Dennis McNally was the Grateful Dead’s publicist from 1984 to 1995 and worked for Grateful Dead Productions and RatDog after that. He published his history of the band, A Long Strange Trip, in 2002.

My very fine editors suggested that since I was telling these musician’s stories of their conversion to Dead Head-edness to you, I should share my own. We’ll skip over the musical instrument part, since you’re not interested in very bad junior high school violin playing, and get to me and the Dead.

In the spring of 1967, I was a high school senior in a small town in Maine. I didn’t fit in—on reflection, not many people really do—and my refuge was the public library, where I did a lot of reading. I still remember the pictures from the Be-In (January 14, 1967) of Jerry wearing his Uncle Sam top hat. It sure looked interesting, but I didn’t have a clue what it would mean to my future.

That fall I was a dj at my college radio station, and came across the Dead’s first album, and “Morning Dew” entered my life with a vengeance. Along with Billie Holiday and John Coltrane, it was a regular in my rotation. For some odd reason, though, I lost touch with the band for a while, and it wasn’t until the fall of 1971, in graduate school, that I met the guy who walked me across the threshold of Dead-dom.

Chris was a really, really brilliant mathematician, and also the only guy I knew of where I lived who smoked dope. I was truly impoverished, and when I apologized for not having any weed to share, Chris would reply, “Hey man, dope is like manure. It only does some good if it’s spread around.” In addition to being kind, Chris was a true Dead Head: we listened to them and only them, Hot Tuna being the only permitted exception. I might add that this was before tapes were common, and I’m talking about records here.

On October 2, 1972, along with a bunch of friends up from the Bronx, Chris took me to my first concert, at Springfield Civic Center, and when we got there, told me to open my mouth. I owe Chris (rest in peace) a very great deal.

He’d also given me a good shove in the direction of working on a book about Jack Kerouac, and by 1973 I had conceived a grand plan to write the history of underground culture in America after World War II in two books: Volume one would be Jack Kerouac and cover the ‘40s and ‘50s, and Volume two would be the Grateful Dead. It took some doing and a lot more time than I counted on, but eventually, that’s what I did.

Of course, I didn’t have clue number one about how I was going to get the members of the G.D. to go along with this idea—for starters; their telephone number was unlisted. I published the Kerouac book (Desolate Angel) in 1979 and sent copies to Garcia and Hunter, and then more or less waited. That fall I sold the idea of writing a piece on Dead Heads and New Year’s Eve to the San Francisco Chronicle’s Sunday magazine—I figured I could introduce myself to the band that way—and in January of 1980, I went to interview Bill Graham, since his number was in the book.

And that’s where Dead Head synchronicity started to kick in. Bill’s secretary was a member of the tribe named Jan Simmons, and after a great interview with Bill, who loved talking about the Dead and Dead Heads, she said, “You know, you ought to talk with Eileen Law at the Dead office. Here’s her number.” Eileen, being the complete sweetheart that she was and is, came to work on a Sunday (I was working a regular job), and we talked for a couple of hours.

Long story short, the Dead announced their 15 night run at the Warfield Theatre, the Chronicle ran my story, Eileen included me in a group of Dead Heads who met Jerry, Tom Davis, and Al Franken as part of what would be the video of the Halloween at Radio City show, Dead Ahead, and when I met him, I asked Jerry if he’d seen the Kerouac book I’d sent him. You have to understand that Kerouac was a life-long hero and role model for Jerry, and yes, he’d read it, and was, ahem, enthusiastic about it.

So enthusiastic, as a matter of fact, that a couple of months later he sent Rock Scully (publicity) and Alan Trist (music publishing) to meet with me. They said, “Jerry says why don’t you do us?” (Do a biography of the Dead.)

Which seemed like a good idea to me, having been dreaming of it for seven years.

I spent the next three years (1981-1984) very happily digging away. I found Phil’s music teacher at College of San Mateo (who had a tape of Mr. Lesh in the CSM jazz band, both playing and the composer of pieces). I dug up lots of Jerry folk and bluegrass music, getting to know Rodney Albin, one of the great people in Jerry’s early life (and I was lucky – we lost Rodney in 1985). I found Gert Chiarito, who ran the “Midnight Special” show on KPFA that Phil engineered and Jerry played on.

And I went to lots of Dead shows, both in the Bay Area and further away. Eventually, the crew decided I could be tolerated, and I spent more time on stage (seriously, a tough transition – it sounds better out front). I spent lots of time at the office, talking with people and seeing how it all worked in business terms. And overall, I managed not to piss off anybody too terribly much, which was important, because in the world of the G.D., just because Jerry had an idea didn’t mean everybody was going to jump up and salute.

One day in June, 1984, Mary Jo Meinholf of the office staff sat up at a company meeting and said, “What are we going to do about the media? They call, and nobody returns their calls (Rock had gone away to get healthy), and they annoy me.” And Jerry said, “Get McNally to do it. He knows that shit. Send him up to my house, and I’ll tell him what to do.” So I went up to his place for my job training. He said, “OK, first thing is, we don’t suck up to the press.” I think I even wrote it down. And then he said, “Ah, that’s enough. Here, toke on this.” Nice training.

I tried to keep working on the book while being a publicist, but it was impossible. It was the greatest job I’ll ever have, but I’m not joking when I say that it was 60 hours a week when we were off the road, and more when we were on. I put the book on hold, but kept a notebook in my pocket to write down the interesting or funny stuff I saw, and there was plenty of that: Jerry and Vice President Al Gore discussing John F. Kennedy’s desk (Bill Clinton had gotten it from the Smithsonian), Jerry talking with Tony Bennett before a San Francisco Giants baseball game, Phil encouraging Brent when B. brought up the idea of playing “Dear Mr. Fantasy,” Branford Marsalis playing like a god, and on and on.

All of which was summed up one disgusting day in Washington D.C., at RFK Stadium. Disgusting because of course if we were playing at RFK it was summer time, and summer in DC invariably meant 100 degrees and close to a 100 percent humidity and we—staff and crew—were out there for 10 or 12 hours. We were leaving the stage and heading for the vans back to the hotel, and Ram Rod, the crew chief and one of the greatest men I’ve ever known, said, “At least it’s not a real job.” And it wasn’t. It was at times more stressful and gritty and challenging than a “real job,” but it wasn’t just a job. Instead, it was an amazing adventure, an incredible opportunity to serve a higher purpose, a chance to help save the world. (Well, we tried, honest).

We couldn’t save Jerry – or he couldn’t save himself – and that sucked, but along with all Dead Heads we honored the music, and I’m really proud of that. See you down the road, maybe even at Ventura.