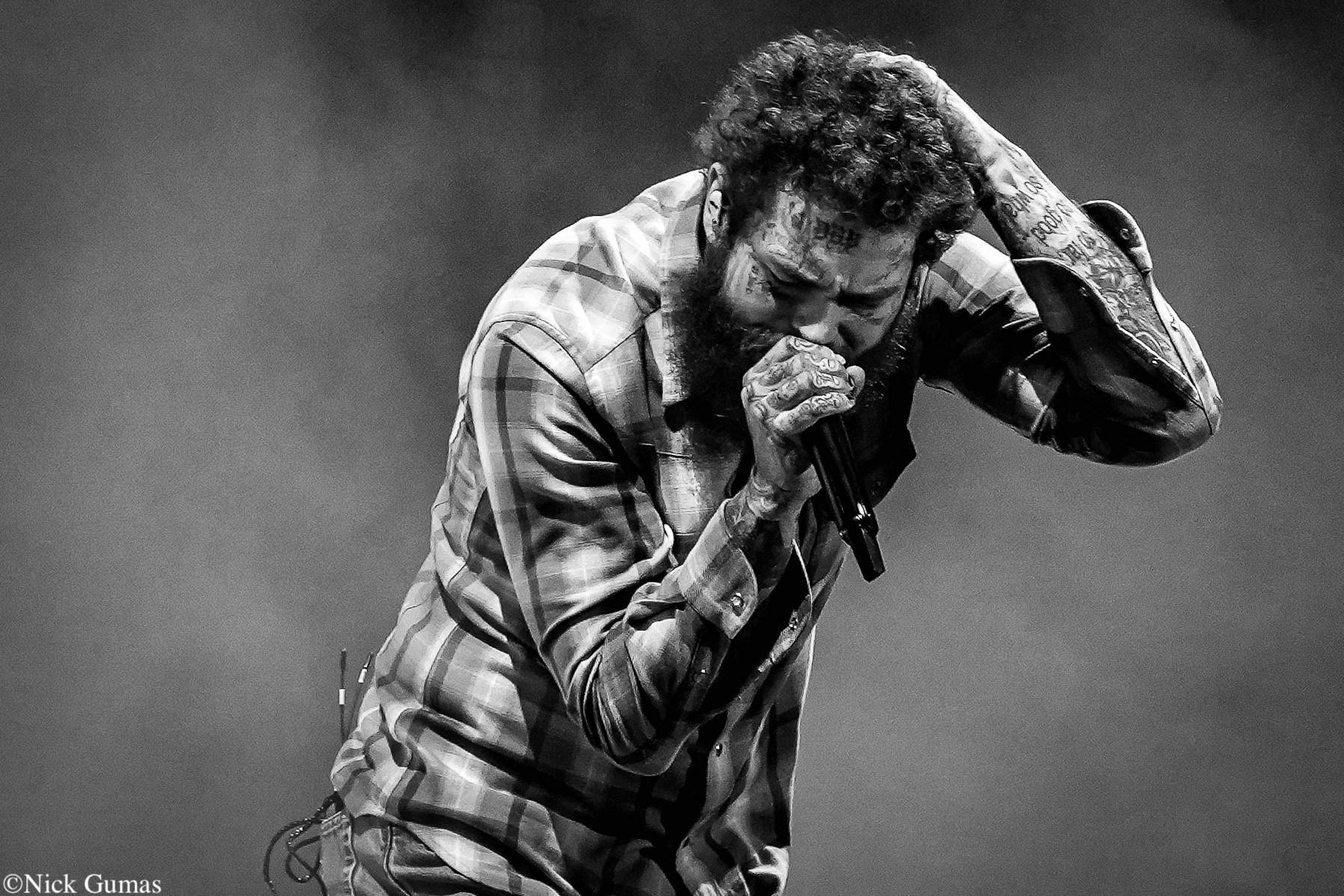

After an illustrious career that speaks for itself, David Hinds and Steel Pulse have forever shaped the history of music. The first non-Jamaican artist to win a Grammy for reggae, he has had a presence in the community since its grassroots days, and his influence is undeniable. We got a chance to sit down for quite a while with Hinds at this year’s Cali Roots festival. In this time, we got quite glimpse into his mind and his thoughts on modern reggae.

More than 40 years in the spotlight has not dampened Hinds’ playful attitude. In our first few minutes with him, his good nature was put on full display. Welcoming us into his room warmly, he was open and conversational and even hid our audio recorder for a quick moment as a joke that brought a smile to our face. Throughout our interview, Hinds was more than candid with his views of the world as he remarked on everything from our current political system to his opinions of social media, and even the part he once played in prompting a small government revolution (no, we’re not making this up.) Be sure to check out their newest album “Mass Manipulation” out on all streaming platforms now.

Grateful Web: How does it feel to be at the 10th anniversary of Cali Roots? Where do you see its place in reggae history?

David Hinds: Well it’s special that it’s number 10, then. I feel that this whole reggae thing along the Californian soil has become like family to us as a matter of fact. There are so many acts that either come from Hawaii or the West Coast that seem to gravitate to the Steel Pulse experience, and we feel amazed and honored about that. So yes, it’s fun to be recognized and to be asked to perform at a milestone in the career of Cali Roots.

GW: Jumping into something more political. We live in an interesting time in political history. How much further behind are we in 2019 in respects to tolerance than you thought we would be by now decades ago when you wrote songs such as “Ku Klux Klan” and why do you think society is in this state?

DH: Society is in this state because of being mass manipulated. It’s been in this state because of politicians that are not sincere to the people, greed, religion that’s been under the guise of trying to promote peace when in fact it does the opposite, and as long as these negative ideologies persist and exist, you find that time will stand still in comparison to what we were up again 40 years ago when we did songs like “Ku Klux Klan.” I mean we have versions of “Ku Klux Klan” like “Don’t shoot” on the album, “Justice in Jana” and so many more that show some kind of racism. If you listen to the sentiments of “Rize,” you can see that we’re trying to convey elements of racism to an extent, and we’re trying to let people ‘rize’ in every sense of the word above all that negativity that’s out there and everything that’s going on out there.

GW: Where do you see the role of Social Media in perpetuating love, hate, and where do you see the trade-off?

DH: Well, social media is a very, very funny thing, and there’s a very thin line between all those entities. Where social media becomes beneficial, take for example that situation that started seven or eight years ago in the middle east where countries like Yemen and Egypt, and Tunisia, and Syria, and all these countries saying “wait a minute” and recognizing that they got the power to make differences to the dictators that have been in power for 30, 40, and in some cases 50 years. So, it was social media connecting the dots and inter-relating with each other, and everybody realizing that they’re not alone with their sentiments, and their own beliefs and their ideologies are running parallel with everybody else in different parts of their region, and they made changes. Bam, Mubarak gone. Bam, Ben Ali gone. Bam, Muammar Gaddafi went. And I’m not saying all these guys were bad guys, but what I’m saying is people realized through the efforts of social media, that they could connect the dots and make differences in their own region, so that’s the beneficial part. The flip side of that coin is when it comes to social media; a lot of the times it’s what one can inject into social media as advertising is what you get out of it. I’ve come across stories that I’ve known to be true as a kid growing up, and when I go back into the website, Wikipedia and all those informational little pages, they give me a completely different story than I know actually happened 30-40 years ago, and I say “wait a minute, that didn’t happen." A good example is Bobby Womack, there was an incident many years ago where someone reported his brother was murdered by one of his wives, and it was really an accident, and when you read the story, it’s a completely different story than what actually happened and you go “wait a minute” so I see how those controlling social media can change the reality of situations. So those are pros and cons when it comes to social media, and the advantageous part when it comes to social media, especially in the case of music, we as musicians, especially as reggae musicians, have been given a raw deal, I don’t know if I’m at the shitty end of the stick. A lot of majors that attach themselves to us in the first place, or vice versa, weren’t doing us any favors. So, we reached a place, now, in the whole scheme of things where we don’t need majors anymore to continue with our liberty. Where the middle man who’s taken the biggest chunk of it all for the least effort is no longer there, these are the pros and cons of social media.

GW: In the spirit of this global mindset, this year’s Cali Roots lineup announced many artists from the UK such as yourself, The Skints, and UB40. How do you see reggae’s influence past just the UK, US, and Jamaica, and what do you think is pushing it on a global scale?

DH: Well, what I like about the reggae music worldwide is that it made us and our predecessors realize that our efforts of trying to make the music happen on a global scale have not been in vain. When we see act like those that are there in Chile, Venezuela, various parts of Africa, parts of Europe, and they’re all here in the United States where America was behind big time when it came to having an organic sounding reggae band coming out of this country. I mean it’s a population of 330 million people here and has been for quite some time, and I know from coming here for many, many years, you couldn’t get a decent reggae band out of the entire population, but now it's there. So, this is what’s pleasing is that people have incorporated the music, and people have recognized different facets of the music, whether its dancehall, ska, roots reggae revival, but the general platform, where the dots are all connecting with all these bands across the planet is that they recognize the efforts of the generation that made it happen in the first place, and the way it’s introduced to them which was introduced to them in an organic kind of way with a one drop groove, the trying to be as meaningful as possible about what you’re saying and trying to live up to a lifestyle that is not subjected to all the trapping and trimmings of all the other genres of music like rock and roll or jazz that you can tell that they all associate themselves with heroin or cocaine, but the general populous of reggae since Rastafari has been the backbone, and for them to recognize the music in the first place on a spiritual and a political level, many participants have not engulfed themselves in drugs that are detrimental to their lifestyles, detrimental to themselves, and detrimental to the what the music stands for.

GW: Obviously, you have had a career that has left an impact on the genre. Can you give one example of a time when you saw the fruit of your influence and felt humbled?

DH: Wow. 1993 is a very significant year as far as I’m concerned when it comes to what happened and what we think we’ve achieved as a milestone in my career because it was one of the first times we went to New Caledonia, and to see how the people were vibing on our music, and if you’re not familiar with New Caledonia, it’s an island off the in the south pacific with Melanesian ancestry as opposed to Polynesian ancestry, and they were governed by the French, and they’d been protesting for many, many decades for independence or to be separated from the rules of the European, and we got caught by being invited there only to find out that we were a political tool to help them liberate their country. So, we felt honored, I mean it backfired on us because had we known we would have been up against that kind of thing we probably have said: “wait a minute, we don’t know about that.” But we got there and realized that these people were using us as a political tool for their liberation and how they took us around their cultures and how they still retain it, how they eat food, how they speak their language, their tribal practices and everything else, it was far removed from how other islands had been governed and controlled by European rule, so I was very much touched by the influence we had on that kind of entity. Come 360 degrees, come January of 1993 there we are standing outside the white house performing under the instructions of Bill Clinton that he wants a particular song performed by the band as he leaves in his motorcade after being sworn in as president of the United States. So, we’re touched by that. People say “Rasta is all about politics,” but this is where Steel Pulse has always been a cut above the rest because we built our music off of political issues. It’s undeniable. The world is disproportional because of politics, how can you not be involved in politics when the world has been sliced up, carved up, the fact that you’ve got to hop on the bus to go to school at a particular time and come back home, you got to leave school at a particular age and now you’re a man and now you’re allowed to vote, you’ve been governed all the way through politics and you don’t want to be part of it? Be part of it.

GW: What’s next for Steel Pulse?

DH: Let’s face it, the next album has taken a while to come out, it’s finally out there. Several songs to wrap our heads around. We’re sitting back to see what songs the people are going to gravitate toward. It’s the early days where you sort of monitoring things on the internet and see how people are responding to the tracks. So far everybody likes the entire album, but no one’s saying “this is our track” so far there’s a couple of people liking “Rize” and people liking “The Final Call” but what’s next for us is because there’s so much information on the album, we’ve got to process it all and get it ready for tours that are going to last as long as 18 months on and off. That’s the furthest we can go right now and hope that other things develop along the way in regards to other things that can happen when it comes to the album making some indentation in history whether that’s in the charts in the period of moments that it deserves to be. We’re hoping that other things can be spin-offs from what we’ve achieved here. Who knows, maybe another inauguration?

GW: You’ve had an incredible career, an I’m sure you’ve had interviews on every subject imaginable, but what’s one aspect of Steel Pulse that you’re not prompted to talk about enough and you think the world needs to know more about?

DH: The color of our underwear? Haha. You know, I’m very much a private man, so you wouldn’t see me on Big Brother or any of those other programs. Having said that, I’d like to know that they’ll be some kind of biography or autobiography that comes out where I can sort of introduce the backbone to what we’ve been about over time. I’d like the word to know that although we’ve got a 40-year legacy, it hasn’t been an easy one. And to keep the music alive, and to keep everyone’s heads on the same page in regards to a band in reggae music, which does not see the units that everybody else sees in their genres of music. That journey has not been an easy one, and for them to bear that in mind every time that they see things that aren’t working the way they think it should be working that nobody is dead from the neck upwards and that opportunity needs to presents itself. The biggest thing in the world is is trying to convince the industry at large that the music has always been a force to be reckoned with in itself and why not have bands like us on major prime time when it comes to the Grammy awards and all these awards that have always been dished out year and year out on national TV.