The last day of the second annual Music on the Mesa festival started out with blue skies and fluffy clouds, but the weather bureau promised rain. Here in New Mexico, we dance about that, especially in monsoon season, because it is arid here. With that in mind, I came prepared with my raingear to protect my camera.

On the patio stage launching today’s musical treats was The Noseeums, a local acoustic act that is really good. This group normally does old-time and bluegrass tunes, I was told, so I was surprised by their inclusion of a Django Reinhardt instrumental. The ukulele player has a unique touch on his instrument, playing it more like a mandolin. His technique sparkled on that tune. Sweet, sweet stuff.

The Noseeums’ set did have a lot of old time classics like “Nine Pound Hammer” and Bill Monroe’s “Cheyenne.” and “I was very impressed with their mandolin player’s vocals on “White House Blues,” written by Charlie Poole and the North Carolina Ramblers and recorded by Bill Monroe. He has a unique quality in his voice I haven’t heard before.

But it was their novelty tunes, like “Plastic Jesus,” (that I haven’t heard in forty years) that connected with this audience. I heard verses to this song I’d never heard before. From what I understand, The Goldcoast Singers wrote only a couple of verses and the chorus, which is what I’d heard other musicians record. Ernie Marrs developed it further, adding more verses, and that’s the version these guys used. It was always funny but the new verses I heard were a great addition.

On the main stage. The Far West band returned to give us another dose of really great road-tested Southern rock, even though these guys are from Los Angeles. In truth, that true Texas sound comes from the collaboration of Texas native Robert Black and New England born Lee Briante, who sings lead on all the songs. Opening with “Long and Dusty Road,” their set list blew away and these young veterans just winged it. There were nice 3-part harmonies on “Bound to Lose,” a nice rockish tune.

Always tight, this band delivers quality every time they set foot on stage. Today, their piano player pounded out honkytonk piano one minute then switched to hard-driving rock. Other players stepped up per usual, adding to whatever subgenre they were playing. And frankly for a California band, I’m always impressed that they can slide into Red Dirt Country so easily. They did a mix of fast danceable tunes and mellow, reflective ones.

Their version of “Hey Maria” was outstanding. Lee Briante’s delivery had a lot of John Prine’s quality and phrasing. It wasn’t an intentional affectation, but something Briante slips into once in awhile. His voice is versatile but is very much Lee Briante. The other band members offered beautiful backup, creating lovely four-part harmonies.

One of my favorites that they do is “Pancho and Lefty.” It’s delivered with a plaintive tenderness that the song deserves. That sensitivity was echoed in their version of “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” a song we’d heard the day before by Wayne Hancock who sounded just like Hank Williams, Sr. Briante’s delivery on this was just as heartfelt but with a difference. I think it’s because it’s coming out of young vocal cords and a younger life that somehow understands the isolation of those simple words.

Since it was Sunday, I’d hope someone would do a gospel tune. The Far West didn’t do that but they gave us the next best thing. They offered a Woody Guthrie musical social commentary, as he always does, that he’d written to the old gospel tune, “I Can’t Feel at Home in This World Any More.” Woody’s take was “I Don’t Got No Home in This World Any More.” It was a nice ending to a fine set.

On the patio stage, Sammy Brue returned, but this time with an addition. His original songs which he accompanies by guitar, harmonica, and kick drum, were given color by a female fiddle player by the name of Juliette Camille. Now approaching fifteen, Sammy Brue’s songwriting is maturing, writing about working and love and facing life. Some people have wondered how much this Utah-based youth (whose parents fully support his music) could know about life to write deep songs. But it’s clear from his early days of busking, recording, and touring, he knows what life on the road is about, what the music business is, and what heartbreak and struggle are. This was his last performance before moving to Nashville to record. We all wish him the best as he expands his career.

From the patio stage, Stephen Plyler directed festivalgoers to the main stage where Robyn Ludwick warmed up. He quoted me from last year’s review of her, saying, “This girl has balls.” And she does because of her songwriting risks. She writes from the male point of view often and writes in waltzes most of the time. She shared a mix from past albums and a few teasers from her new one coming up.

She began her set with a song she co-wrote with Jasmine Morris, a 16-year old Australian girl who wanted to write a country song. The result was eventually recorded by Hank Williams, Sr.’s granddaughter and it will be out later this year. It was a sweet little country tune and kept Robyn’s strong writing sense.

Every time I hear Robyn Ludwick, I’m always impressed with her fresh turns of phrase. This makes her work bold and sometimes shocking. Phrases like “…you won’t leave and I can’t stay,” “… let me standing at the wishing well,” and “I’m not a beauty queen; I’ve never been….I’m a dime store legend” stick with you. She writes about the most unexpected people, not those you’d expect in country or even Americana songs. She writes about strippers, junkies, social rejects, fallen women, and troubled relationships. But through them all there is a resilience, a strength that reaches out to these souls instead of condemning them.

Singing some of my favorites, Robyn graced us with “Mexia” and “She’ll Get the Roses.” The latter one makes me cry every time. It’s about the Other Woman and how she’s left with the dregs of life while the wife gets the roses. Damn! A fine song.

What she calls “the most offensive song I ever wrote” turned out to be a song taken from something her big brother, Charlie Robinson, jokingly used to say. It’s called “Texas Jesus.” I listen hard to this one but I didn’t see the offense she thought it had. But maybe it’s because I listened with a writer’s brain and not a religious one.

Robyn delivered one powerful song after another. But it was “Freight Train” that really stood out. It indicts the underbelly of the music industry. You expect it from Hollywood, but not from Nashville. The chorus runs: “I’ll buy you a freight train and a honkytonk bar if you’ll be my baby tonight.” I think in reality the hyperbole of those two objects is just as telling as what the real promises were: a record deal and a tour.

I can’t wait to listen to Robyn’s new album and savor her words and delivery.

On the patio stage, Decker brought something very unusual to this festival. He had a mix of punkish, psychedelic rock that edged into Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit” delivery. Decker, the frontman for his band, has a high tenor range that surprised me. It’s not a falsetto. It is just slides into a woman’s second soprano range. I mention it only because I had to make sure Decker was actually singing some of these songs when I heard them. It’s an advantage because it allows him to pursue genres that a lot of performers can’t. Though he’s billed as a folk/gospel/rock performer, his writing and his band’s execution are often dark, edgy, and completely impossible to categorize. But he and his band are very good.

After Decker, the wind kicked up and rain fell. Stephen Plyler moved The Masterson’s inside gig up from its 7 pm slot to 5:30. This brought most of the crowd inside, while others took shelter under vendor tents.

The Mastersons did a fine hour and a half set. I completely enjoyed their harmonies and the variety in their set list. But the space was crowded with people trying to dance, and I was dripping water from the plastic poncho covering my camera so I stepped out and found dry space under the merchandise tent. I wished I’d heard more from The Mastersons. I’ll check out some of their recordings for sure.

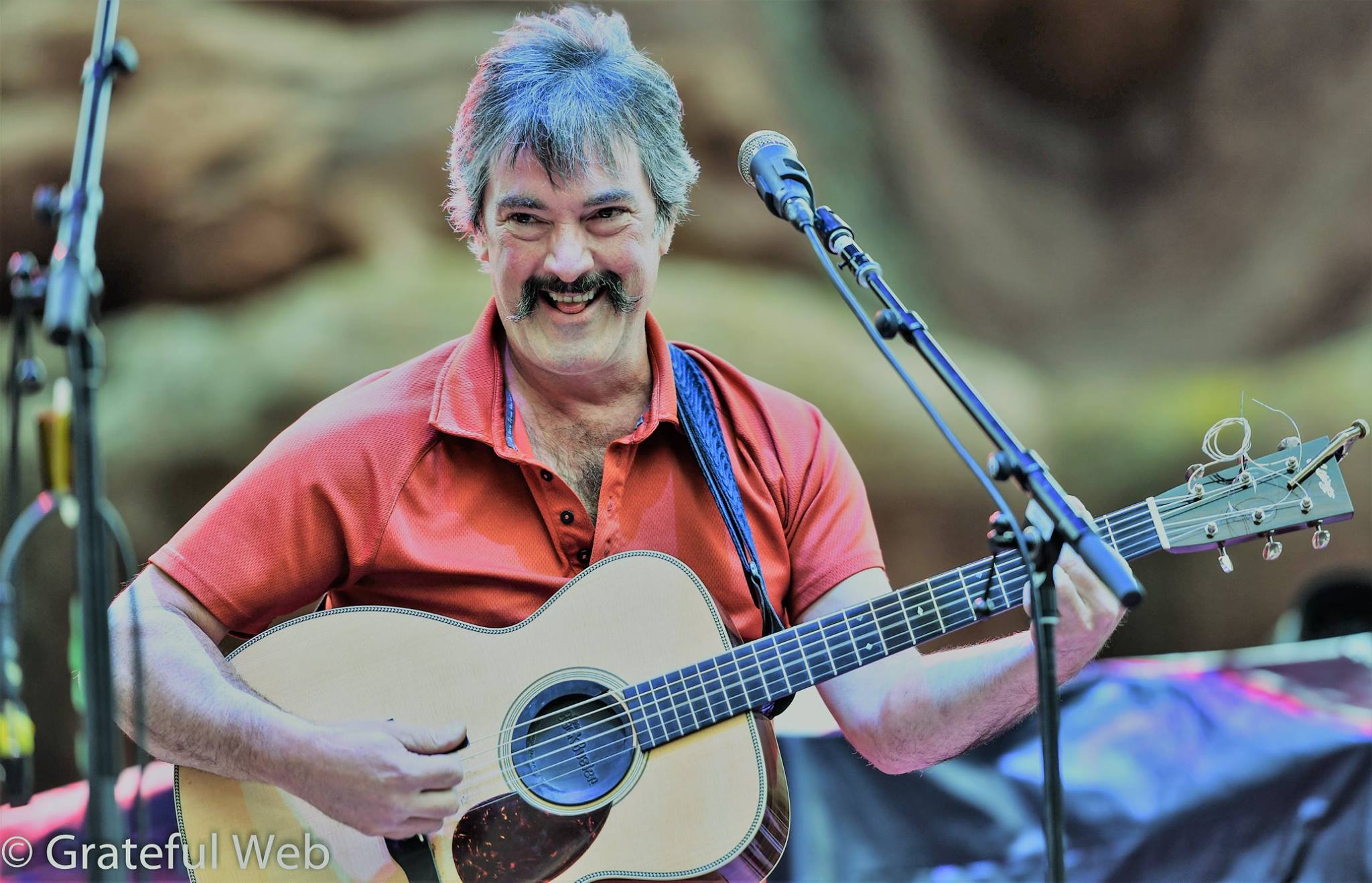

The rain stopped and Ray Wylie Hubbard and his band took the main stage. I am embarrassed that I just now discovered him at my age. This songwriter is an icon. He brought out hit after hit, pure crowd favorites and obviously songs he enjoyed. Right out of the shoot, he did “Snake Farm,” a song I’d been hearing my Oklahoma festival-mates raving about. Dang! Great rootsy, swampy sound with a heavy drum beat.

There were great story songs, like “Name Dropper, about Mambo John, an Austin TX drummer who died. There was a cowboy-type song that was also earthy and bluesy. He did “Redneck Mother,” that Jerry Jeff Walker made famous and I never realized was Ray’s song. He’d written that in Red River NM almost four decades ago. He commented about it, saying, “When you write a song, you ask yourself if you can sing this for 38 years?” Well, it’s that good of a song, and he can.

I was totally blown away by this man, his songs, and his sound. And the audience agreed. I appreciated his “Charlie Musselwhite Blues” because, like Ray, we’ve both been in awe of Charlie Musselwhite. I did share a story with Ray backstage after his set about interviewing Charlie Musselwhite.

Ray Wylie Hubbard was the only one who chose to do a gospel tune on this Sunday, something that all country performers did at every show; there was at least one. But the one he chose was what you’d expect from only Ray Wylie Hubbard: “John the Revelator.” It was a gritty, swampy grisgris that underlined the Black Gospel roots of the song, and one that could only be sung by Ray and his band. We all had church, whether the festivalgoers knew it or not.

Afterwards, Ray said, “I don’t want to leave you with something that greasy.” So he ended his set with “The Messenger,” a tender, sweet song. Trust me, I’m going to be at the front of the stage at the next Ray Wylie Hubbard show and there is one coming up next month here in New Mexico.

Ray’s son, Lucas Hubbard, joined him on this tour, playing guitar.

While the main stage got ready for the headline act, Kelly Mickwee drew festivalgoers inside for a half hour of her original music. The rhythm of acts, in spite of wind and showers, was seamless with little idle downtime between acts.

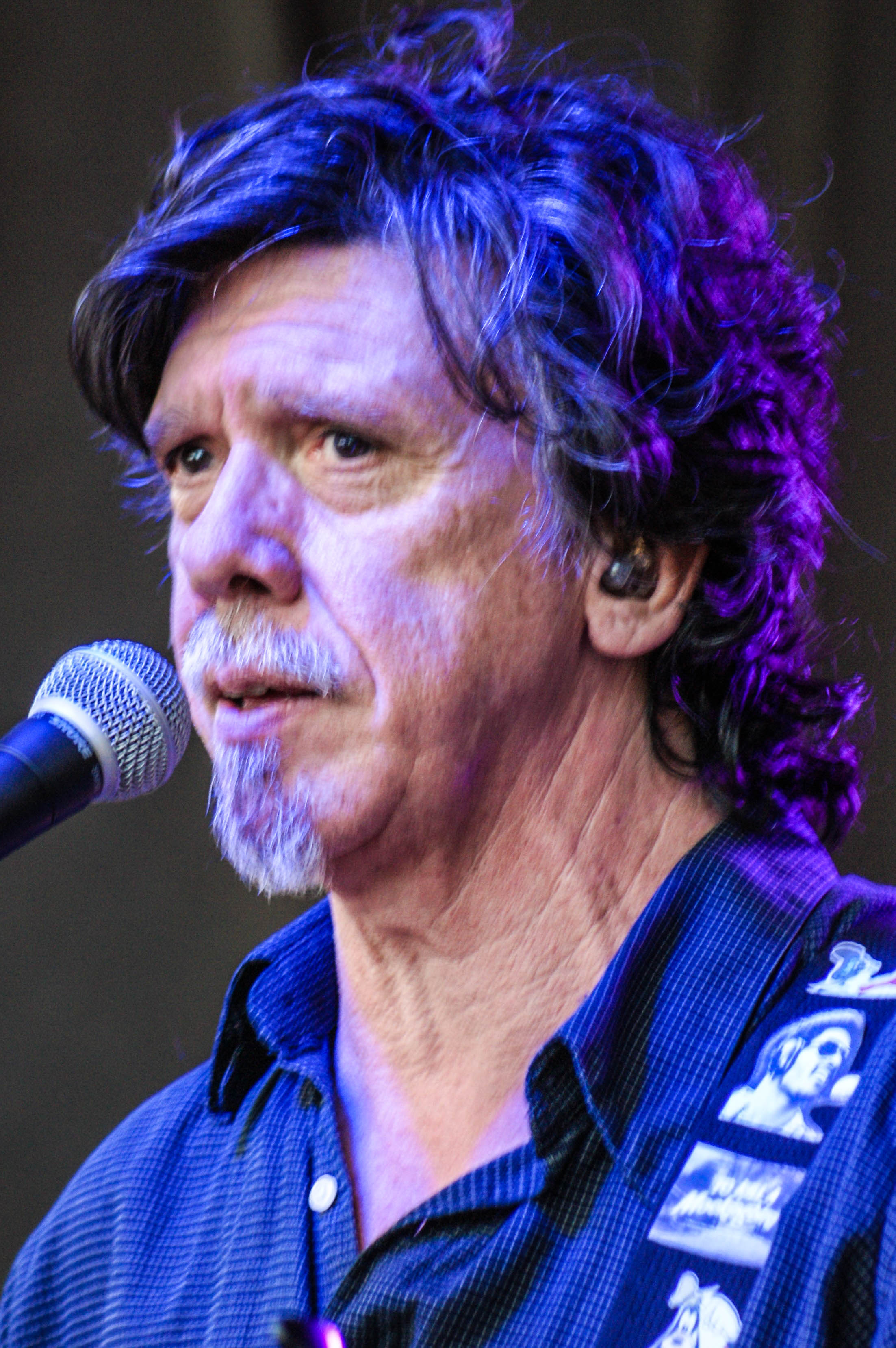

Finally, the long awaited set by Shawn Colvin and Steve Earle. The audience crowded the foot of the stage, drawing people up from their chairs to see more.

It was a simple act, just the two singer-songwriters. I’d followed Steve Earle’s career for some time and had even interviewed his sister, Stacey Earle. And last year his son, Justin Townes Earle, played the first Music on the Mesa festival. I didn’t know Shawn Colvin’s work as much. I’d found Steve Earle’s writing to be unusual slices of life, quirky and often profound.

I expected some incredible song selections and some fresh new writing from this musical collaboration. However, in pre-press about their new album, I found out it was mainly covers they had decided to do as duets, with only a sprinkling of co-written songs. They are both very unique writers, coming from very disparate points of view. So this tour was highly anticipated.

When they launched into the Everly Brothers’ “Wake Up, Little Suzie,” I wondered about that choice. Of all the zillions of songs to choose from, they chose a fifties tune. Hmm. Then they moved into an Emmylou Harris tune and finally broke into some individual song sharing, Shawn Colvin first; later Steve Earle shared his; alternating back and forth throughout the evening. They sprinkled in more covers and finally shared some new co-written tunes. It was an odd mix, very unique for them, but it may have been what transpired as they both shared their favorites over the many decades they have known each other.

Finally, bringing the festival inside, New Mexico artist, Boris & the Saltlicks, ended the night and the second annual Music on the Mesa to a close. It was a fine celebration of music, introducing new artists, hosting icons, and bringing back old favorites. Next year’s festival will be just as smooth with a kick here and there, like aged whiskey. I can’t wait.