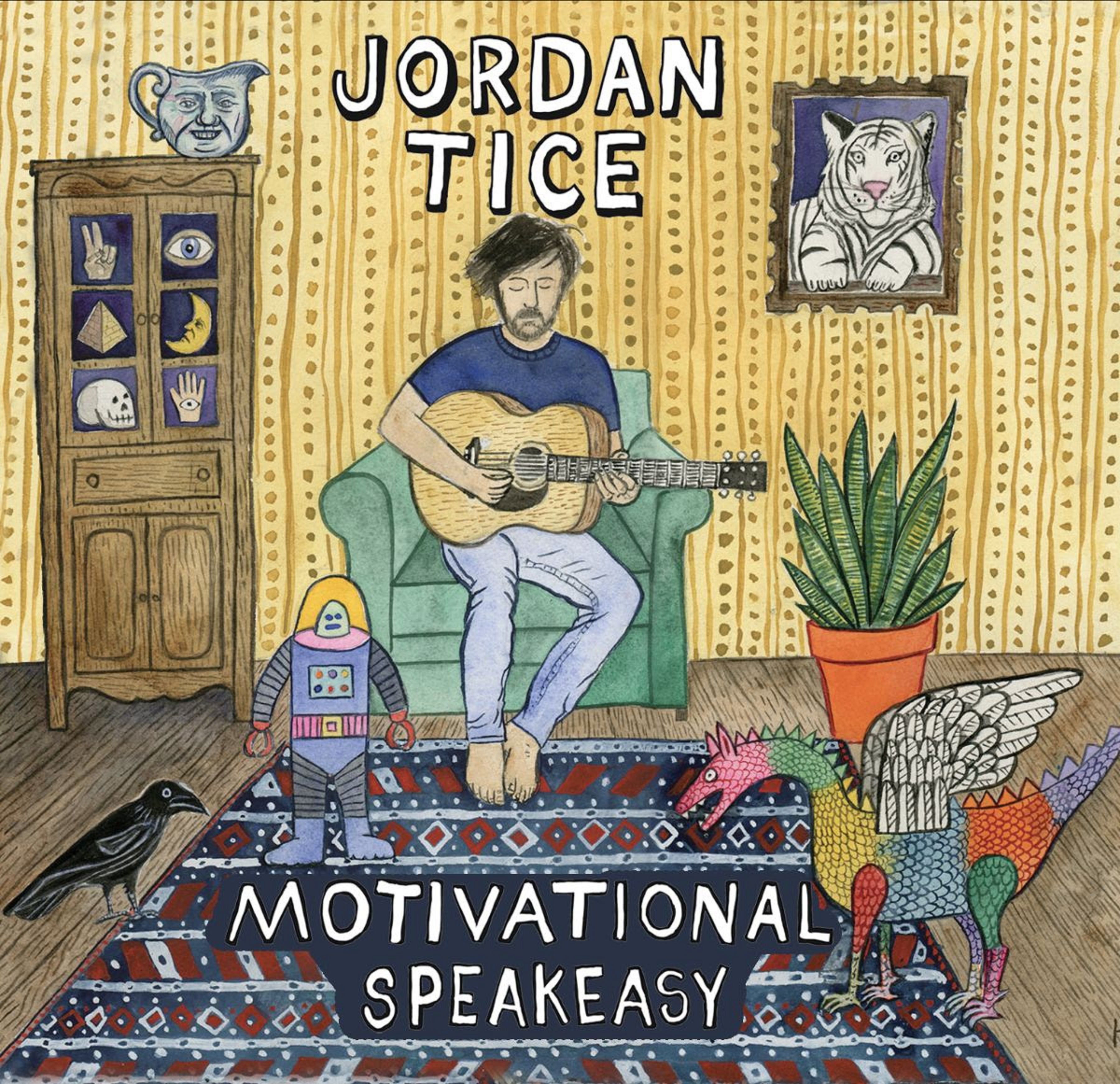

It’s not that Jordan Tice is living on the fringes of Nashville, holed up during quarantine in a little house in Madison, Tennessee. It’s that he’s living in a Nashville that’s based more on the community roots of the music than on the glitz of country stars in secluded recording studios. He’s living in a Nashville that’s moved even beyond East Nashville’s underground Americana scene to a more free-wheeling house session community based in Madison. Late night cosmic Americana picking parties at Dee’s Country Cocktail Lounge, or back porch sessions within spitting distance of John Hartford’s cottage next to the lazy Cumberland River, it all lends a spontaneity to the music that’s based on the joy of invention and creativity and less on finger-busting virtuosity. Tice is a collaborator by nature, known for his work with groundbreaking progressive stringband Hawktail (featuring Brittany Haas and Paul Kowert of the Punch Brothers), but his new album, Motivational Speakeasy (coming September 25, 2020), is a solo affair, just Tice and his beloved and well-worn Collings guitar. Hawktail’s music showcases Tice’s remarkable instrumental skill, and here his guitar work is as crisp and intricate as ever, informed by everything from classical ragtime to psychedelic newgrass. Produced by close friend Kenneth Pattengale of The Milk Carton Kids, the focus of the recording was on finding the heart of Tice’s original songs and instrumentals, and showcasing his deep explorations into American fingerstyle guitar, nodding to purveyors such as Leo Kottke, John Fahey, Mississippi John Hurt, Norman Blake, and David Bromberg.

John Hartford remains a touchstone for Tice, and you can hear much of his influence on the new album, from the talking blues of “Walkin’,” which Tice wrote while wandering New York waiting for a flight to Finland, or the dark, existential humor of “Creation’s Done,” which imagines a vanished creator’s note to his creations left behind on his fridge. “Bachelorette Party” sounds at first like a Hartford instrumental romp, but the simple feel of this piece belies much deeper structural conceptions, reflecting Tice’s belief that something can seem simple yet still be made with great craft. Tice, like Hartford, loves to play with familiar forms of American roots music. “Artists like Hartford or Norman Blake chose to look beyond the idiomatic elements of the music,” Tice explains, “and tap into where those things came from. They aligned themselves with the lineage and personalities behind the music. They learned from literal examples, but they were working more off abstractions that they absorbed into their own work, creating something entirely new.” Both Hartford and Blake were always creatively their own people, beholden to no expectations and infused with a kind of existential irreverence. These are examples that Tice works to uphold, or as he says, it’s about “experimenting to find ways that you can express yourself in a way that adds up to yourself.”