On April 2, 2011, the band known as LCD Soundsystem ceased to exist. During a sold out show at Madison Square Garden, James Murphy, the founder of LCD Soundsystem, and a bunch of his best friends came together to play their last show ever. It was almost four hours in length, featuring special guests Reggie Watts, members of Arcade Fire, and many others. Attendees were asked to wear only black and white. Murphy wrote on his website, "If it's a funeral, let's make it the best funeral ever!"

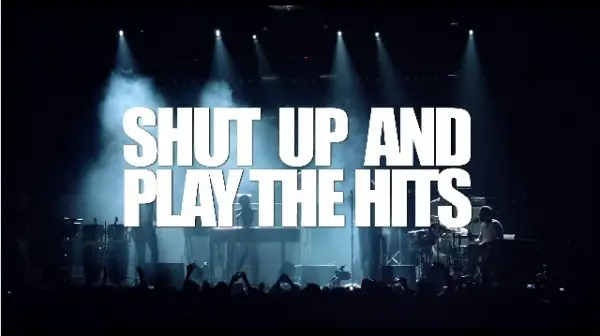

Almost a year and a half later, the documentary Shut Up and Play the Hits was released to select theaters, documenting the final days of the band. Most showings have sold out, and new showings are popping up to meet demand. It's as if many fans were not there to see the movie itself; they wanted to be as close as possible to an LCD Soundsystem show. Seeing a documentary of the band on the big screen is probably the closest they'll get from now on.

Many readers are probably wondering, "Who's LCD Soundsystem? How could they sell out Madison Square Garden? How did they even draw that big of a crowd?" Explaining this involves a bit of context.

LCD Soundsystem were one of the first groups labeled with the genre "dance-punk." As the name explains, it's a hybrid of electronic dance and punk rock from decades ago. And overall the band is a tough egg to crack. Some songs are straight pop you'd hear on the radio. Some songs recall The Beatles and other British Invasion bands. Some songs are as furious as the Sex Pistols or as repetitive as an LP run-out groove. Songs could as be as silly as Daft Punk playing a gig in your house. Other songs could be as deep as ruminations on the idea of getting older. Given all of this, LCD weren't really dance-punk. They were another band who bounced between styles on a whim, creating music they wanted, when they wanted. And slowly but surely, they gathered a following.

Like a train gathering steam, their fanbase grew, hanging on to news updates, planning on going to shows months in advance, and writing overly wordy essays about them on music sites. It wasn't a rabid group of people who wanted every piece of the band they could get. It was more a reverent group of people who saw the band as a talented group of musicians. And talented they were. But in the end, it was still a project, not a functioning band. Murphy was the only one who really wrote the music, and he’s been getting on in years. He started LCD at age 30, and ended at age 41. It didn’t feel right to him to keep on going as an old man breaking his body during tours. And so, he decided to end it all on a high note.

Like a train gathering steam, their fanbase grew, hanging on to news updates, planning on going to shows months in advance, and writing overly wordy essays about them on music sites. It wasn't a rabid group of people who wanted every piece of the band they could get. It was more a reverent group of people who saw the band as a talented group of musicians. And talented they were. But in the end, it was still a project, not a functioning band. Murphy was the only one who really wrote the music, and he’s been getting on in years. He started LCD at age 30, and ended at age 41. It didn’t feel right to him to keep on going as an old man breaking his body during tours. And so, he decided to end it all on a high note.

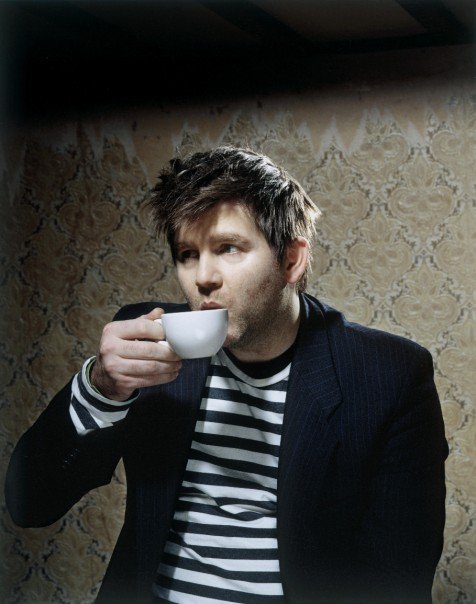

The film starts out with the crew setting up for the concert, but instead of blasting headlong into the thing, we're taken to Murphy's home the night after the show. He's slow to wake, ignoring calls on his phone, and playing with his dog before getting out of bed. In another scene he's in a cafe doing an interview about the end of LCD with Chuck Klosterman. Murphy’s honest and verbose answers for the interviewer are spliced with more of Murphy's morning routine. He looks old, worn-down, and hungover. Everything he does is slow and deliberate. Then it transitions to a frenetic live performance of one of LCD's songs.

This is how most of the movie goes. James Murphy meets with his manager, talking about the final concert. Then there's a fan-favorite song playing. Then another interview question is asked, with the audio played over another scene with Murphy slowly getting through the day walking his dog and cleaning up his studio. It sounds pretty formulaic, but it's actually quite exhilarating.

The two major parts of the film, Murphy's morning-after motions and his life as a leader of a band, provide a stark contrast that doesn't seem to get old. It's a sensory overload at one moment, and solemn silence the next. Fans of the band are just playing the guessing game with the director. "What song will he play next? Is this going to be the end of the movie? Will there ever be a moment where James Murphy isn't incredibly self-conscious?"

The answer, to at least that last question, is no. Murphy comes off as one of the most honest people out there. This leads to problems; at times he is blunt, other times pretentious, but he's always stood behind his statements, no matter how blunt or pretentious. Murphy admits in the interview that he does like talking about himself. If people ask, he will answer. That same ethos is reflected in the music. Songs are cheeky, deep, or something in between. The band is not afraid to do something uncool or meta. Some songs even lampoon the exact genre they're pushing. And somehow all of this comes together in about 100 minutes of film.

The answer, to at least that last question, is no. Murphy comes off as one of the most honest people out there. This leads to problems; at times he is blunt, other times pretentious, but he's always stood behind his statements, no matter how blunt or pretentious. Murphy admits in the interview that he does like talking about himself. If people ask, he will answer. That same ethos is reflected in the music. Songs are cheeky, deep, or something in between. The band is not afraid to do something uncool or meta. Some songs even lampoon the exact genre they're pushing. And somehow all of this comes together in about 100 minutes of film.

The crowd at the Roxie Theatre was antsy, waiting for the hits to be played and the celebration to start. Many were kicking back with some smuggled-in beers, talking back to the screen, and rocking in their seats. Slowly but surely, people stood up and started dancing in the aisles, jumping around like it was a real concert. They clapped after each live segment. Some people were singing along. When the ban finished with their trademark closer "New York, I Love You But You're Bring Me Down," people in the aisles held up their lighters in salute. Surely this was against building codes, but they didn't care. Some were drunk on cheap beer. Others were drunk on music. People were smiling and laughing with each other.

The film ended with that song, and so did LCD's career. Exiting the theatre, hordes of moviegoers outside smoked cheap cigarettes and talked about the here and there; it felt like a concert had just ended. That's probably what the film was aiming for. As it goes with any band that breaks up, the months immediately following the announcement are the ones that sting the most. People sift through the band's discographies listening to their choice cuts. Live bootlegs are shared like crazy. People who missed out realize they missed out. And anything remotely connected to the defunct band is taken with overwhelming enthusiasm.

In 2003 James Murphy came onto the scene with "Losing My Edge," a tune about feeling outpaced by kids who were much younger than him. But in 2011, Murphy showed that he still had quite a big lead. LCD Soundsystem was a band that put on a great live show, touched many people's hearts, and retired at the peak of their abilities. It's saddening to know that they're over, but it was wise to take the difficult way out, when ideas are still fresh in contrast to the end when the well of creativity has run dry, and the shows stop selling out. Shut Up and Play the Hits is food for the fans who miss LCD Soundsystem. For the fans who got into them too late. It's a reminder that even when they're gone, a band still has power. The legacy remains in the tape, and the collective consciousness of the people who can say with pride, "I was there."