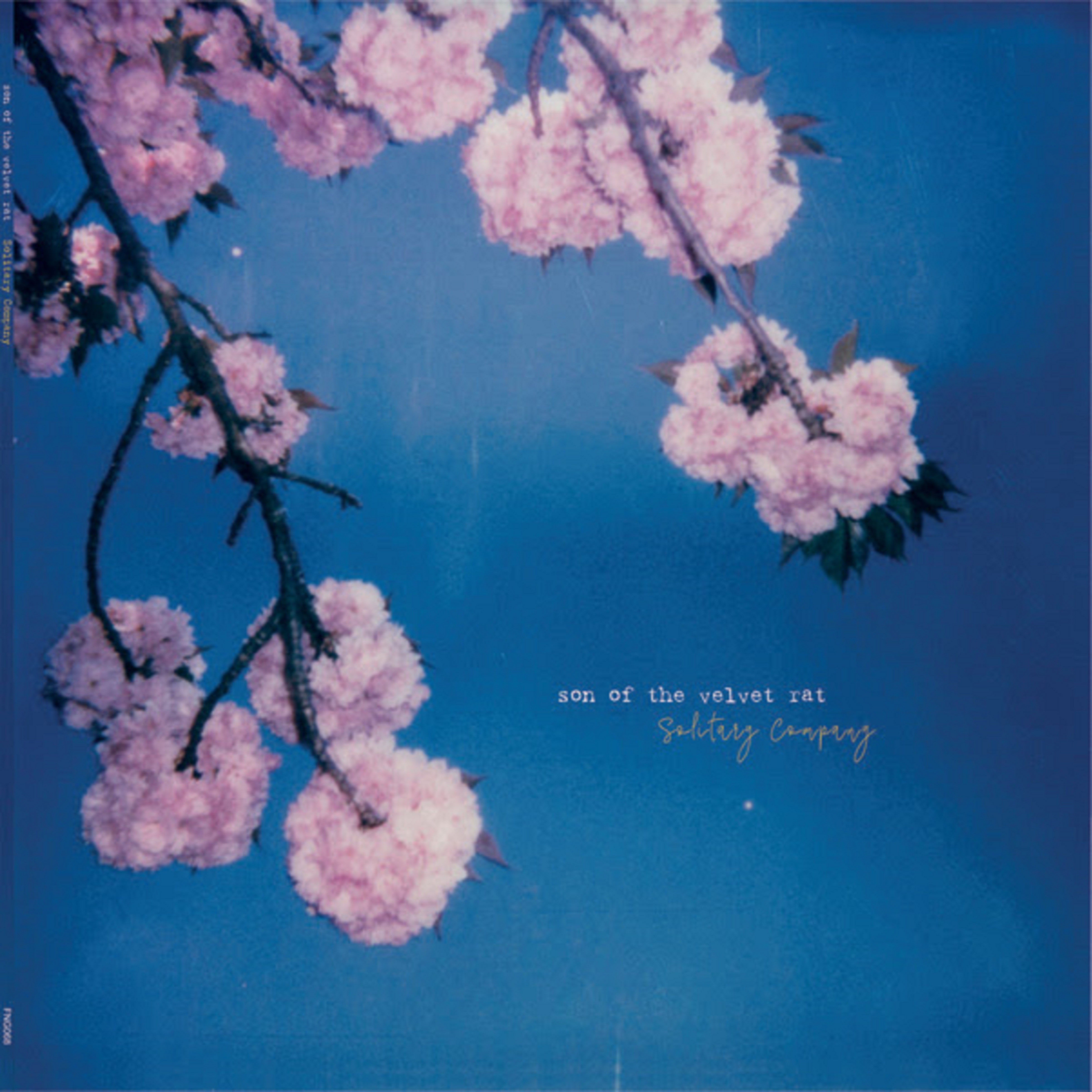

Son of the Velvet Rat is the solo musical endeavor and masked identity of Georg Altziebler and his wife, Heike Binder. In 2013 the duo left their hometown of Graz, Austria for the endless highways of America, finally settling along the edge of California’s Mojave Desert, in Joshua Tree. Their new album, Solitary Company, will debut internationally on March 19, 2021, released in the U.S. by tastemaker indie Fluff & Gravy Records.

From Paul Cullum’s liner notes:

Situated at the vanguard of Euro-Folk Noir, their songs build on the cabaret traditions of Old World masters like Georges Brassens, Jacques Brel and Fabrizio De André, now fused with the dark Old Testament prophecy and Kabbalistic visions conjured by New World visionaries Townes Van Zandt, Leonard Cohen or Bob Dylan.

The result is like some exotic desert fruit — equal parts bruised pulp and scarified skin, set off against the crepuscular glow of the violet horizon or blood pooled on the desert floor — all delivered in what accidental fan Lucinda Williams calls Georg’s “great sexy-gravelly voice,” leavened by Heike’s translucent harmonies, like roses circling a tattooed heart.

The album’s title track opens with a faint sigh from the melodica before the band joins in. They’re playing a slow march, treading gingerly. Everything is sparse — piano, organ, guitar, drums, double bass — all adding up to the restrained suggestion of a potential wall of sound while playing as little as possible. A half-minute in, the great Bob Furgo’s violin takes over with a tune that’s equally Irish folk and “La Vie en Rose,” instantly placing us in that American/European world he used to evoke on those old Leonard Cohen records. “I’m the paintbrush, not the painter,” Georg Altziebler sings softly, setting the tone for ten story-songs that appear to tell themselves without effort. “I am just the singer, not the song / All I really did was sing along,” he deadpans. It’s a neat play on an old cliché, using the familiar as an elegant entrance to an original vision.

“I’m gonna take Avalon to Landers Brew,” Altziebler sings on “When the Lights Go Down,” name-checking the road that leads to the bar where he and Heike have played many a show on a small semi-circular stage. We might be in a film noir (“Wash the blood away from your fingernails / Get rid of the gun on Sun Flower Trail”) or in the middle of a climate change-induced apocalypse. For all of its local references, this is far too surreal to be a folk record. Rather, it inhabits “a secret parallel world behind the clouds,” in the words of “Beautiful Disarray.”

While their previous long-player Dorado took them to the Culver City, Calif. studio location of producer Joe Henry, the new album was recorded mainly in the very landscape referenced in the lyrics — inside the Red Barn at the end of a dirt track near Morongo Valley, Calif. — a place filled with lovingly restored vintage amps, keyboards and recording gear by its owner and the album’s co-producer, Gar Robertson. Additional recording in Graz, Austria (by Fabio Schurischuster at Die Mischerei & Günther Kolman at Nasaomusic) seamlessly ties together the Old and New World visions that are intertwined at the core of the band.

Other lyrical scenes paint a picture of a Ferris Wheel spinning underground, or a couple gambling all their money at the roulette table on “11 & 9” (November 9th was the date of Heike and Georg’s wedding anniversary). There’s the midsummer night’s magic of “The Waterlily & the Dragonfly” and a couple seen making love from the windows of New York City’s Carlton Arms Hotel in the album’s eerie title track. It all ends in the haunting “Remember Me,” the story of an old fisherman left behind by his family.

Not many records manage to take the listener to so many places with such subtle tones and gestures. At Son of the Velvet Rat’s California performances you’ll see eccentric desert-dwellers mouthing their lyrics back at them. They have become an integral part of the Joshua Tree music scene, which holds this mysteriously charismatic couple of Austrian immigrants in increasingly high regard. On the evidence of Solitary Company, it’s easy to see why.