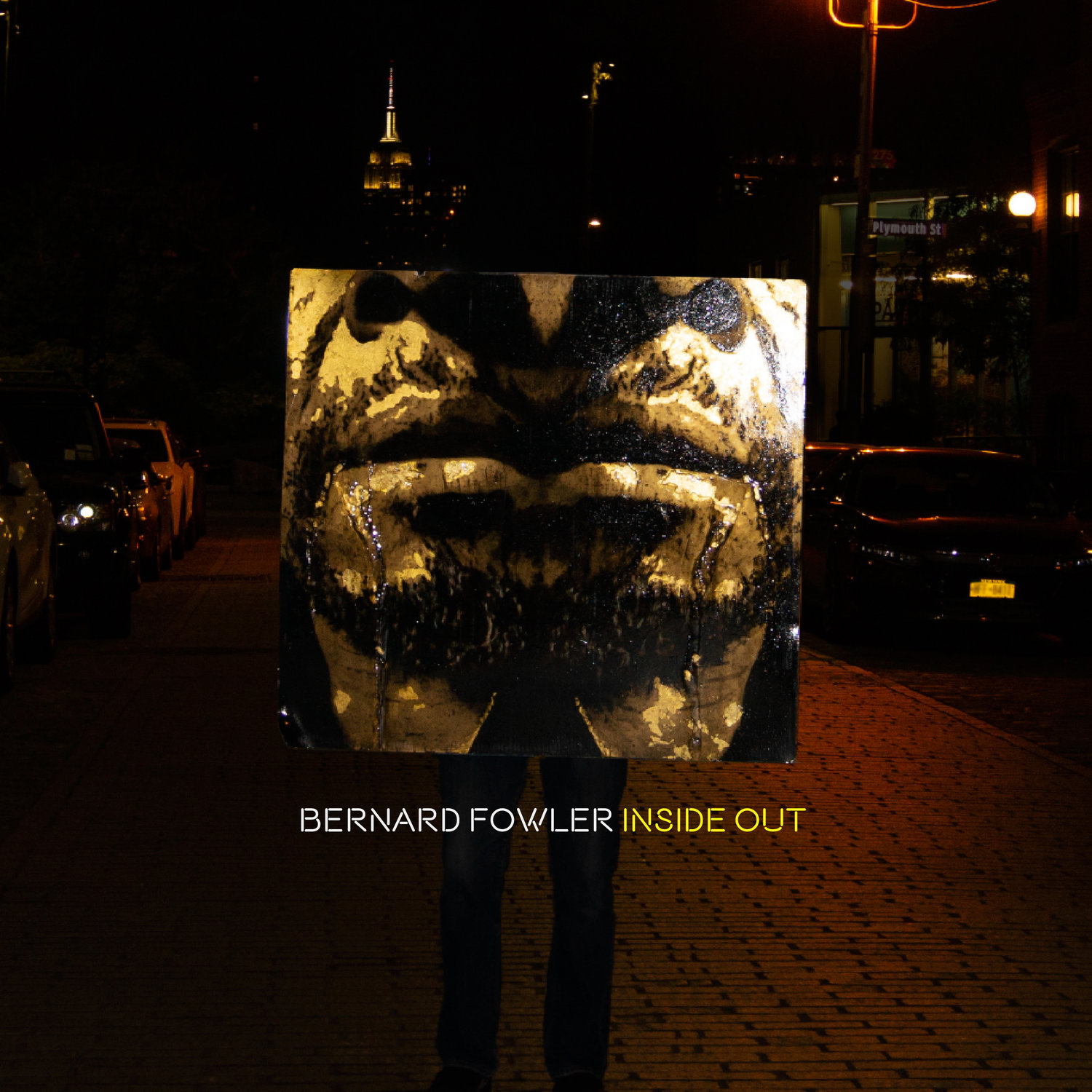

“It’s Rolling Stones songs deconstructed,” says Bernard Fowler, explaining the title of his new album Inside Out. “I just took these songs and turned them inside-out.”

Fowler is an arty guy, so when he makes an album of Rolling Stones covers, it’s going to be something out of the ordinary. Back in the day, he sang with the groundbreaking dub-electronic band Tackhead as well as downtown avant-funkers Material; along with iconic DJ Larry Levan, he was a founding member of the New York Citi Peech Boys, who emerged from Manhattan’s fabled early-’80s house/garage scene. Blue-chip visionaries like Philip Glass, Yoko Ono and Ryuichi Sakamoto have him sing on their records; the guy is on Public Image Ltd.’s landmark 1986 Album and Herbie Hancock’s hit mid-’80s electro-funk albums.

Fowler has another gig too: he’s sung and played percussion with the Rolling Stones, on stage and in the studio, since 1988. At soundcheck somewhere along their 2015 Zip Code tour, he started riffing on a Stones song as dramatically delivered spoken-word — and the band dug it. “Mick said, ‘Bernard, I’ve heard Rolling Stones songs done a lot of ways but never like this,’” Fowler recalls. “I said, ‘Well, you know what? When the tour is over, I’m going to cut it.’ And he said, ‘You should.’ That’s all I had to hear. That was the green light.”

And that’s how it came to be that one of rock and pop’s most sought-after singers doesn’t sing a note on his new record.

The time was right: after two rock-oriented solo records — 2006’s Friends with Privileges and 2015’s The Bura — ”I wanted to do something different,” says Fowler. “And spoken word is definitely different. Things that other people run away from, I run to.” Fowler began poring through the Rolling Stones songbook in search of material. “I found a lot of gems,” he says. “The stuff I wound up using only scratches the surface.”

Lots of people have celebrated Keith Richards’ iconic riffs, Mick Jagger’s trademark howl-and-strut, and the Rolling Stones’ blazing live show, but there’s never been such a thoughtful, soul-baring and thoroughly original appreciation of the band’s lyrics. In order to do that, Fowler pared away the chord changes and even the melodies and left only the words, then declaimed them like the world’s coolest preacher atop slammin’ grooves powered by a who’s who of crackerjack players. It’s not quite singing, but only a peerless vocalist could pull it off so powerfully, his incantations seething with righteous anger, foreboding and desire.

Inside Out doesn’t play to the crowd by covering big hits. Sure, 1983’s “Undercover of the Night” went Top Ten but none of the others charted in the top 40, even the classic “Sympathy for the Devil.” Instead, the idea was to find songs that would not only work in this format but resonate both with Fowler personally and with the current cultural moment; Inside Out isn’t just an insightful and impassioned tribute, it’s also autobiography and social commentary. “It’s a good time to do this record: the world is so upside-down,” says Fowler. “Prejudice, drugs, violence, injustice, it’s all going down.” And so are things like love, lust and mortality — it’s all there on Inside Out. The words might hit even harder than they did in the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s. “We need more power to hold the line/The strength of darkness still abides,” Fowler intones on “It Must be Hell,” and ain’t that the truth.

Inside Out has deep roots in New York City. The influence of the visionary ‘60s proto-rap group Last Poets shines brightly on “Tie You Up” and “Undercover of the Night.” The music of another proto-rapper, Gil Scott-Heron — just one of many legends Fowler has recorded with — is also in the house. But perhaps most of all, look to “Jibaro,” an incendiary poem by Felipe Luciano, a former member of the radical Puerto Rican-American rights group the Young Lords and an early member of the Last Poets. “I saw him recite it on an HBO poetry show and that just rocked me,” says Fowler. “I never forgot it. He’s a really big inspiration for this record.”

That strong feeling of back-in-the-day New York is where the autobiography comes in. Growing up in New York City’s predominantly black and Puerto Rican Queens Bridge Projects, Fowler listened to a lot of funk and r&b. Maybe that’s why Inside Out is laced with references to touchstones like James Brown (“Dancing with Mr. D”), War and the Chambers Brothers (“Time Waits for No One”), Curtis Mayfield (“Sister Morphine”) and any number of ‘70s funkateers. And it just so happens that the first record Fowler’s dad ever gave him was 12 x 5 — the second album by up-and-coming British r&b combo the Rolling Stones.

And then there’s salsa music: Fowler grew up hearing it all around him; musicians would play drums in a nearby park from morning to night. “We woke up hearing drums, we went to sleep hearing drums,” he has recalled. “It’s in my blood and when I hear it, I want to dance.” As the record’s producer, Fowler had percussionist aces Walfredo Reyes Jr. and Lenny Castro play rhythms from Africa, Brazil and the Caribbean, then he’d vocalize over them, usually keeping the first take. And so, for instance, “Tie You Up” is transformed from the Stones’ swaggering full-band stomp to a percolating 6/8 percussion groove.

The opioid epidemic isn’t the only reason “Dancing with Mr. D” and “Sister Morphine” made the cut: it was also from growing up in Queens Bridge. “I grew up with drugs all around me,” Fowler says, adding that a close family member was a long-time addict. “I bore witness to him coming home bloody from owing people money, or stealing stuff out of the house to get his fix. Either you get well and wise or you’re going to die. Luckily, he became well and wise.”

And so for Bernard Fowler, Inside Out brings it all back home. “All that stuff has become a part of me,” he says. “That’s what Inside Out is: all that history is wrapped up in this one project.”

Inside Out is also personal for Fowler because it features so many of his friends. His old pal, the renowned drummer Steve Jordan, heard just one track, called Fowler and insisted, “Yo, man, I gotta play on that.” Jordan wound up playing on not just that track but all the percussion-based tracks. “He wasn’t leaving without playing on all of it,” Fowler says, chuckling. “That was a sign that I was onto something good.”

The full-band tracks feature yet more top-shelf players: long-time Stones bassist Darryl Jones, former Miles Davis drummer/producer Vince Wilburn, Jr., guitarist George Evans and pop/r&b session heavyweight Michael Bearden on piano. Drummer Clayton Cameron, renowned as “the Brush Master,” added extra texture. Then Fowler called in guitarist Ray Parker, Jr. “He came over, plugged in and started playing,” says Fowler, “and I was screaming. Everybody was screaming. He was killing it. Killing it.” Listen for Parker’s work on “Time Waits for No One” and “Sister Morphine.”

Together, they worked some magic. The Stones played “All the Way Down” as a swaggering rocker; here, it becomes wah-wah-heavy guitar-funk; “Dancing with Mr. D” trades in the original’s glossy ‘70s rock for a neck-snapping vamp like something out of a vintage blaxsploitation soundtrack; “Time Waits for No One” retains the original’s inexorable tick-tock but gives it a lithe, ominous overlay, like an ethereal lowrider.

If the trumpet on “Sister Morphine” reminds you of Miles Davis, it’s probably because it comes courtesy of Keyon Harrold, who played all the trumpet on the acclaimed biopic Miles Ahead. On “Sympathy for the Devil,” Fowler wanted “avant garde type of piano.” So he called in beloved David Bowie pianist Mike Garson, who plays an absolute masterpiece of a solo; it’s clear that this is the same virtuoso who took the famous mind-blowing turn on Bowie’s “Aladdin Sane.”

Inside Out demonstrates what cover versions are supposed to be: reinterpretations that are not only a vehicle for personal expression, but also put the material in a new light. “People hear their favorite songs all the time — but sometimes they don’t really hear them,” Fowler says. “This is a way to hear them all over again and appreciate them in a whole new way.” But the beauty of Inside Out is that it provides an opportunity to appreciate Bernard Fowler in a whole new way too.