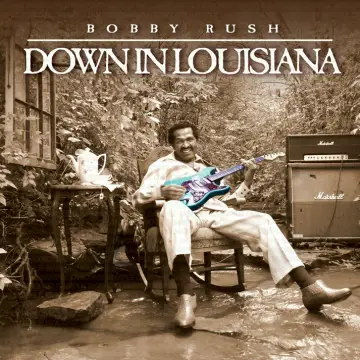

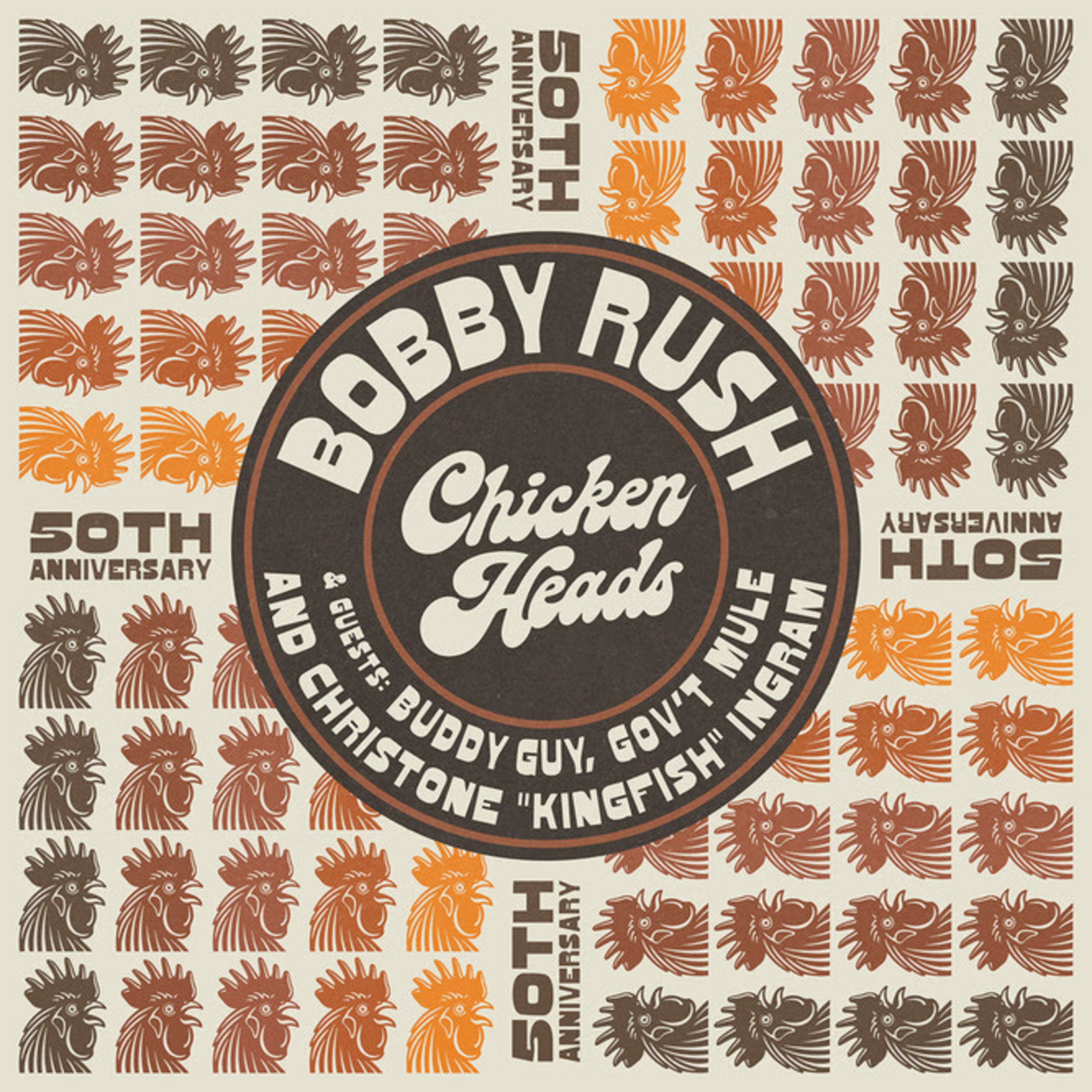

Bobby Rush’s new Down in Louisiana, out February 19, 2013 on Deep Rush Productions through Thirty Tigers, is the work of a funky fire-breathing legend. Its 11 songs revel in the grit, grind and soul that’s been the blues innovator’s trademark since the 1960s, when he stood shoulder to shoulder on the stages of Chicago with Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter and other giants.Of course, it’s hard to recognize a future giant when he’s standing among his mentors. But five decades later Down in Louisiana’s blend of deep roots, eclectic arrangements and raw modern production is clearly the stuff of towering artistry.“This album started in the swamps and the juke joints, where my music started, and it’s also a brand new thing,” says the Grammy-nominated adopted son of Jackson, Mississippi. “Fifty years ago I put funk together with down-home blues to create my own style. Now, with Down in Louisiana, I’ve done the same thing with Cajun, reggae, pop, rock and blues, and it all sounds only like Bobby Rush.”At 77, Rush still has an energy level that fits his name. He’s a prolific songwriter and one of the most vital live performers in the blues, able to execute daredevil splits on stage with the finesse of a young James Brown while singing and playing harmonica and guitar. Those talents have earned him multiple Blues Music Awards including Soul Blues Album of the Year, Acoustic Album of the Year, and, almost perennially, Soul Blues Male Artist of the Year.As Down in Louisiana attests, he’s also one of the music’s finest storytellers, whether he’s evoking the thrill of finding love in “Down in Louisiana” — a song whose rhythmic accordion and churning beat evoke his Bayou State youth — or romping through one of his patented double-entendre funk rave-ups like “You’re Just Like a Dresser.”Songs like the latter — with the tag line “You’re just like a dresser/Somebody’s always ramblin’ in your drawers” — and a stage show built around big-bottomed female dancers, ribald humor and hip-shaking grooves have made Rush today’s most popular blues attraction among African-American audiences. With more than 100 albums on his résumé, he’s the reigning king of the Chitlin’ Circuit, the network of clubs, theaters, halls and juke joints that first sprang up in the 1920s to cater to black audiences in the bad old days of segregation. A range of historic entertainers that includes Bessie Smith, Cab Calloway, B.B. King, Nat “King” Cole and Ray Charles emerged from this milieu. And Rush is proud to bear the torch for that tradition, and more.“What I do goes back to the days of black vaudeville and Broadway, and — with my dancers on stage — even back to Africa,” Rush says. “It’s a spiritual thing, entwined with the deepest black roots, and with Down in Louisiana I’m taking those roots in a new direction so all kinds of audiences can experience my music and what it’s about.”Compared to the big-band arrangements of the 13 albums Rush made while signed to Malaco Records, the Mississippi-based pre-eminent soul-blues label of the ’80s and ’90s, Down In Louisiana is a stripped down affair. The album ignited 18 months ago when Rush and producer Paul Brown, who’s played keyboards in Rush’s touring band, got together at Brown’s Nashville-based Ocean Soul Studios to build songs from the bones up.“Everything started with just me and my guitar,” Rush explains. “Then Paul created the arrangements around what I’d done. It’s the first time I made an album like that and it felt really good.” Rush plans to tour behind the disc, his debut on Thirty Tigers, with a similar-sized group. Down in Louisiana is spare on Rush’s usual personnel, — Brown on keys, drummer Pete Mendillo, guitarist Lou Rodriguez and longtime Rush bassist Terry Richardson — but doesn’t scrimp on funk. Every song is propelled by an appealing groove. Even the semi-autobiographical hard-times story “Tight Money,” which floats in on the call of Rush’s haunted harmonica, has a magnetic pull toward the dance floor. And “Don’t You Cry,” which Rush describes as “a new classic,” employs its lilting sway to evoke the vintage sound of electrified Delta blues à la Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters. Rush counts those artists, along with B.B King, Ray Charles and Sonny Boy Williamson II, as major influences.“You hear all of these elements in me,” Rush allows, “but nobody sounds like Bobby Rush.”Rush began absorbing the blues almost from his birth in Homer, Louisiana, on November 10, 1935. “My first guitar was a piece of wire nailed up on a wall with a brick keeping it raised up on top and a bottle keeping it raised on the bottom,” he relates. “One day the brick fell out and hit me in the head, so I reversed the brick and the bottle.“I might be hard-headed,” he adds, chuckling, “but I’m a fast learner.”Rush quickly moved on to an actual six-string and the harmonica. He started playing juke joints in his teens, wearing a fake mustache so owners would think him old enough to perform in their clubs. In 1953 his family relocated to Chicago, where his musical education shifted to hyperspeed under the spell of Waters, Wolf, Williamson and the rest of the big dogs on the scene. Rush ran errands for slide six-string king Elmore James and got guitar lessons from Howlin’ Wolf. He traded harmonica licks with Little Walter and begin sitting in with his heroes.In the ’60s Rush became a bandleader in order to realize the fresh funky soul-blues sound that he was developing in his head.“James Brown was just two years older than me, and we both focused on that funk thing, driving on that one-chord beat,” Rush explains. “But James put modern words to it. I was walking the funk walk and talking the countrified blues talk — with the kinds of stories and lyrics that people who grew up down South listening to John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf and bluesmen like that could relate to. And that’s been my trademark.”After 1971’s percolating “Chicken Heads” became his first hit and cracked the R&B Top 40, Rush’s dedication increased. He relocated to Mississippi to be among the highest population of his core black blues-loving audience and put together a 12-piece touring ensemble. Record deals with Philadelphia International and Malaco came as his star rose, and his performances kept growing from the small juke joints where he’d started into nightclubs, civic auditoriums and, by the mid-’80s, Las Vegas casinos and the world’s most prominent blues festivals. Rush’s ascent was depicted in The Road to Memphis, a film co-starring B.B. King that was part of the 2003 PBS series Martin Scorsese Presents: The Blues.In 2003 he established his own label, Deep Rush Productions, and has released nine titles under that imprint including his 2003 DVD+CD set Live At Ground Zero and 2007’s solo Raw. That disc led to his current relationship with Thirty Tigers, which distributed Raw and his two most recent albums, 2009’s Blind Snake and 2011’s Show You A Good Time (which took Best Soul Blues Album of the year that’s the 2012 BMAs), before signing him as an artist for Down in Louisiana.Although his TV appearances, gigs at Lincoln Center and numerous Blues Music Awards attest to his acceptance by all blues fans, Rush hopes that the blend of the eclectic, inventive and down-home on Down in Louisiana will help further expand his audience.“But no matter how much I cross over, whether it’s to a larger white audience or to college listeners or fans of Americana, I’ll never cross out who I am and where I’ve come from,” Rush promises. “My music’s always gonna be funky and honest, and it’s always gonna sound like Bobby Rush.”