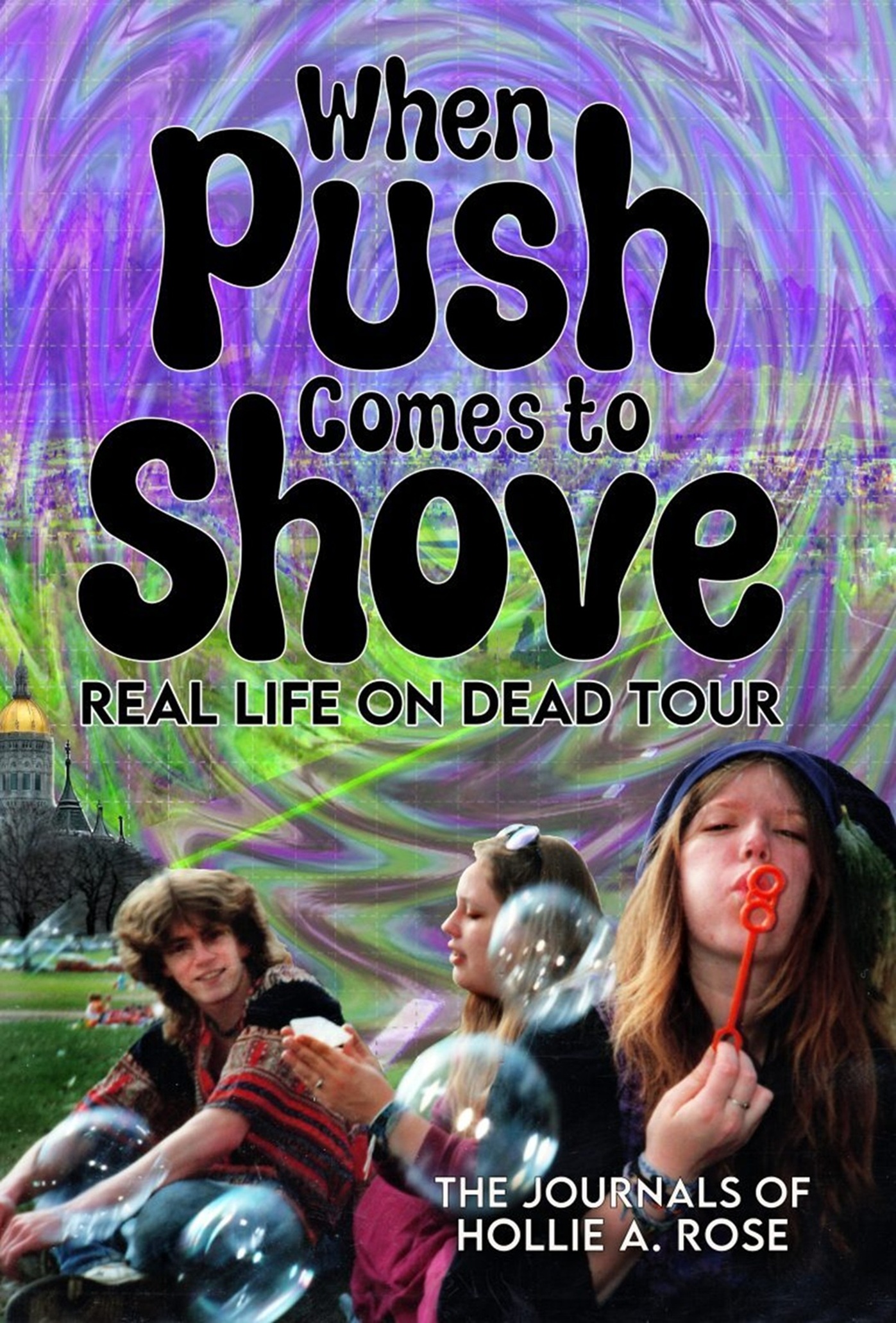

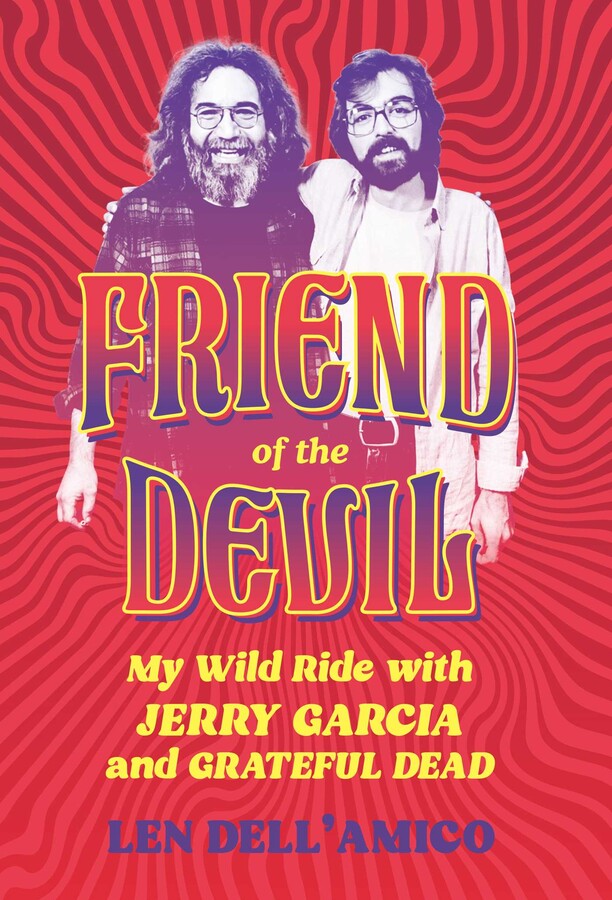

Len Dell'Amico has a shelf full of books about Jerry Garcia and Grateful Dead, but he hasn’t read many of them. On the other hand, he has written one himself that is well worth reading. Friend of the Devil: My Wild Ride with Jerry Garcia and Grateful Dead (Weldon Owen) is now available via the usual online booksellers – and perhaps you’ll see it at your local bookstore too.

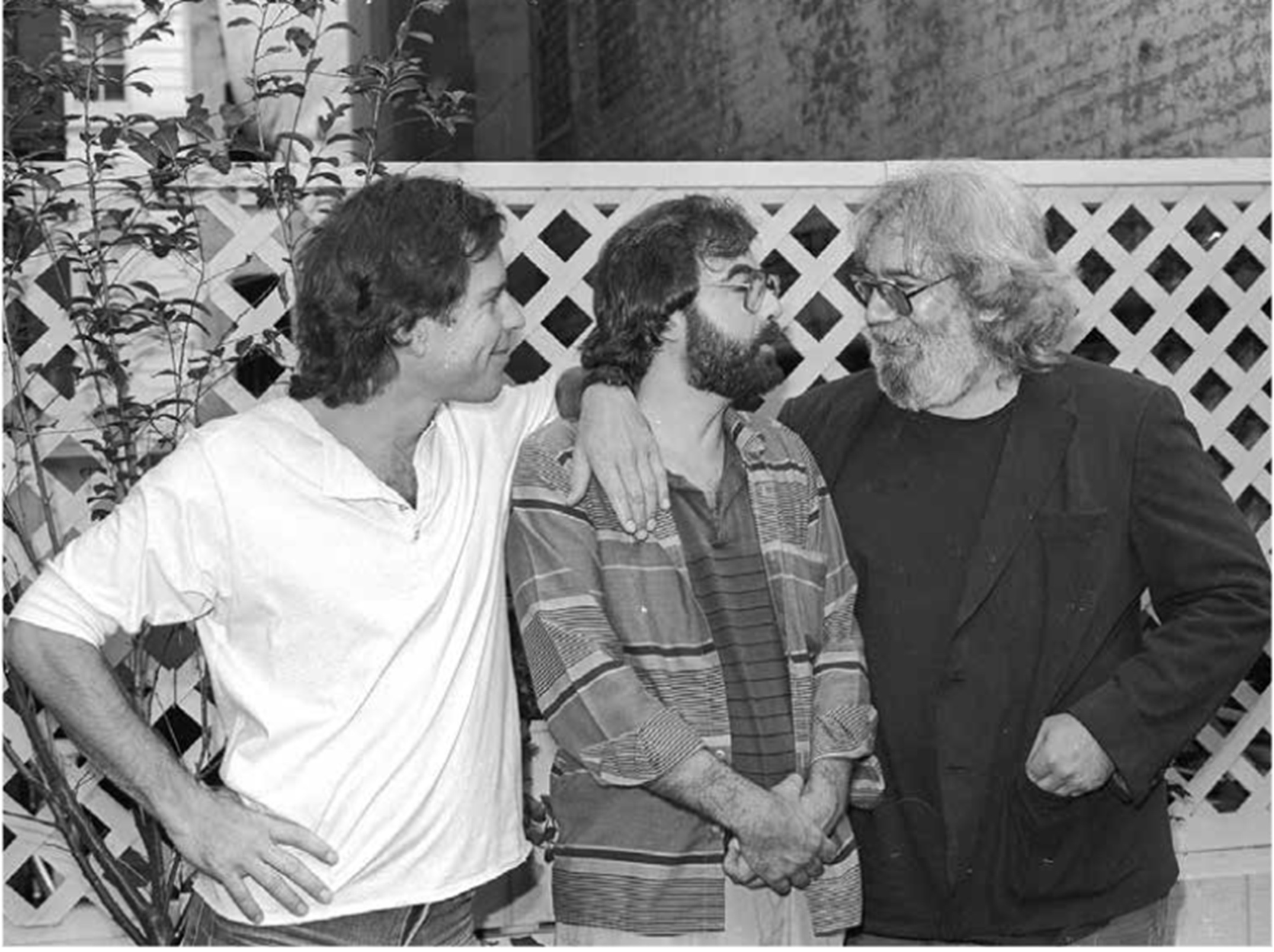

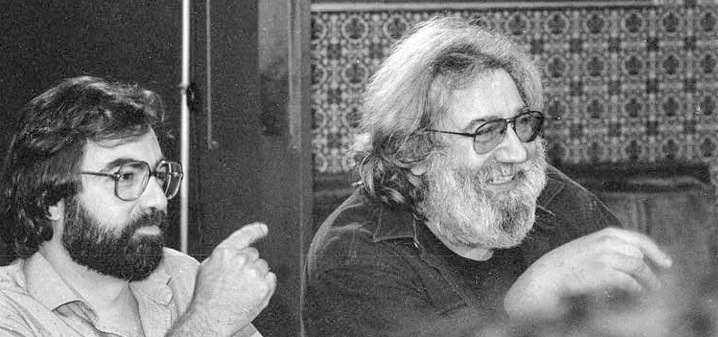

As the Dead’s "video and film guy" from 1980 until Garcia's death in 1995, Dell'Amico was deeply involved with the band on both a professional and personal basis. (Dell’Amico prefers Garcia’s description of him as a "video and film guy" over labels like “producer” or “director.”) During that time, he became a close friend and confidante of Garcia. His memoir is filled with stories and recollections that are at times humorous, often insightful, and frequently intimate.

Friend of the Devil is a must-read for any Jerry Garcia fan interested in the myth as well as the man. Dell’Amico declares on the first page that, “This book is not an attempt at a history or a biography of Jerry Garcia or Grateful Dead.” A reader might debate this claim. Certainly, there is a historical narrative in Friend of the Devil regarding the author’s experience with the Dead as a videographer, producer, director, and creative associate for fifteen years.

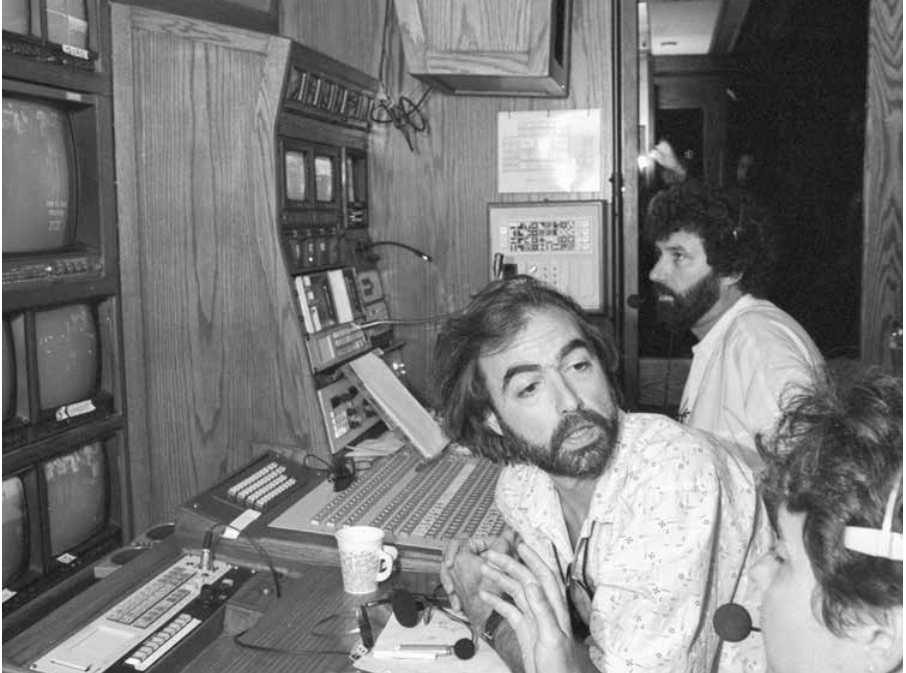

During this time, Grateful Dead, with Dell’Amico as an innovative technical partner, were pioneers of livestream events (both in-theater and at-home) and arena concert video accompaniment. Dell’Amico also worked with the band to produce MTV videos for “Hell in a Bucket” and “Throwing Stones.” He worked with Garcia to direct “So Far,” a best-selling video that melded footage of live stage performances (both with and without audiences) with animated sequences. Friend of the Devil describes these ventures in detail, with behind-the-scenes vignettes as well as a practical assessment of the prescience that drove Garcia and his bandmates to the vanguard of 1980s video representation.

So that’s the history stuff. On the other hand, when it comes to his relationship with Garcia, Dell’Amico is correct to say Friend of the Devil is not a biography per se. Still, the author’s involvement with Garcia, both as a workmate and as a friend for well over a decade, provides ample fodder for a “slice of life” representation of a man who, for many people, was and remains revered with godlike adoration. (Facebook meme I saw recently: “I’m so tired of all these people comparing Jerry Garcia to God. I mean, he was talented and creative and all that – but he’s no Jerry Garcia.”)

Clearly, in Dell’Amico’s eyes, Garcia was, at the very least, uncomfortable with that adoration: “He was what I would call the opposite of a narcissist. He actually worked hard to remain humble, and actively resisted every opportunity to acknowledge how great he was, and also, by the way, how wise and lovable he was.”

One notable segment in the book that underscores this assessment recounts the time when Dell’Amico held Garcia’s Doug Irwin guitar “Tiger” for a moment. He remarked to Garcia that it was a really heavy instrument. Garcia chuckled and said, “Yeah, it’s heavy, you bet, and I gotta stand there for three hours holding it at every show. It may look like magic to the crowd, but a big part of it is just plain, sweaty, hard work.”

Despite bringing Garcia down to earth with stories like that, and in addition to being close friends, Dell’Amico remains a diehard fan too. “I think he is best understood, and revered, as a great musician and songwriter, yes, but also as a spiritual leader, showing us the way to a better world.”

Friend of the Devil is full of great anecdotes that show both sides of Garcia, the myth and the man. And it’s not only about Garcia – there are funny and poignant stories about other members of the band too, and about lyricist Robert Hunter, and about Deadheads and members of the Dead’s crew. There’s also just enough autobiographical stuff about Dell’Amico to give the reader a sense of Who is this guy?! (Along with hundreds of other artists, Dell’Amico also produced concert films and music videos with artists such as Sarah Vaughan, Herbie Hancock, the Allman Brothers Band, and Bonnie Raitt.)

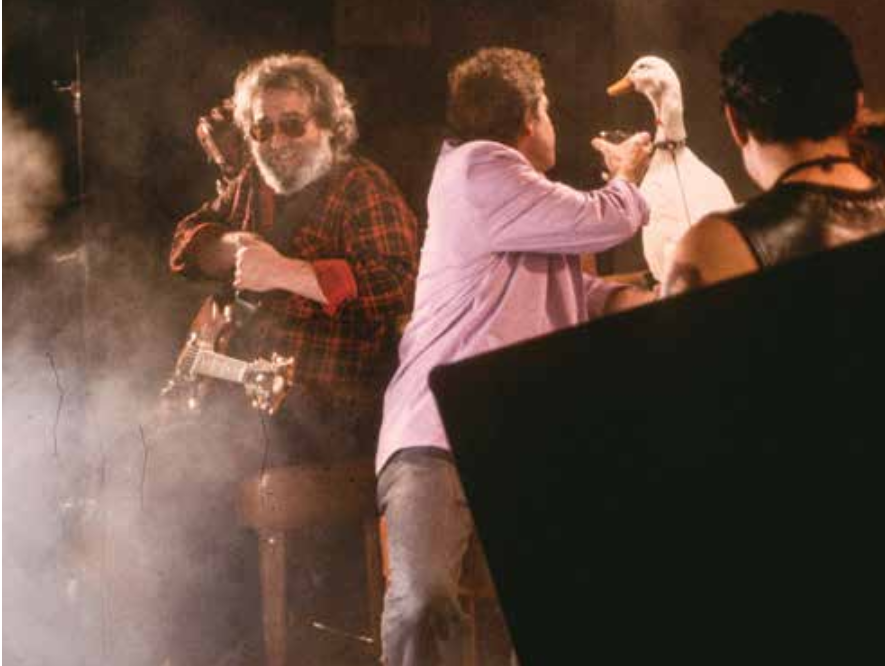

One of my favorite bits includes the sentence, “Then Bobby says, ‘A duck.’” I’ll say no more about that. Read the book to find out: What the duck?!

Dell’Amico lives in Fairfax, California, which happens to be just a few miles from my home. He came over one afternoon in December for what I thought would be a 45-minute interview about the book. We ended up chatting about the book and his experience working with the Dead and being a fan and friend of the band for three hours. Here are some excerpts from our meeting.

MY CONVERSATION WITH LEN DELL’AMICO

Gabriel David Barkin (GDB): Just to lay some common ground for our interview: I saw, as near as I can count, exactly 250 Grateful Dead shows, and all the post-Jerry permutations with Bob and Billy and Mickey, tons of Phil & Friends gigs, etc. I saw my first show when I was 17, in 1980, just after you first started working with Garcia and the Dead.

You and I spent a lot of time in the same world, and we've intersected in a lot of ways. I'm probably in some of your video footage – for instance, I followed that birthday cake to the stage on New Year’s Eve the year when you produced the livestream video, and I was front row at Telluride, which you also recorded. In your “So Far” video from New Year’s Eve 1985, my voice is somewhere in that roar of people in the crowd, because I was at that show.

But to be honest, I don’t think I saw your video of “Hell in a Bucket” until I was prepping for this interview. I think I would remember the duck if I had seen it.

Len Dell’Amico (LD’A): I thought of naming the book “Duck.”

GDB: That’s a great place to start. I want to talk about the title, Friend of the Devil. When people pick up your book, or see it for sale, they're going to see the title, Friend of the Devil. It's about Jerry, of course. And I think the natural assumption most people will have – and I had this assumption myself – is that you are “the friend” and Jerry is “the devil.” And you actually waited until the end of the book before you write about why you chose that title.

Was that kind of purposeful, putting that explanation at the end so people would read the whole book, kind of waiting for the shoe to drop about Jerry being a devil in your eyes when in fact he isn’t that at all?

LD’A: Right. The last chapter, I go over to his house, and he answers the door. He's got a cape. [Laughs.] And all of a sudden, the horns.

GDB: Exactly. Smoke coming out.

LD’A: And I can smell sulfur. Just kidding. Answering your question: No is the short answer. There was no guile to it. I was throwing out names and soliciting from people suggestions. And I threw that out because it's so easily remembered. My daughter flipped and said, That's it! I'm like, oh, she’s Gen Z, and I want Gen Z. The people who were involved in selling books thought it was fantastic. It's just instantaneous. Oh, Grateful Dead. Without having to say, “Grateful Dead.” Although that's in the subtitle.

But then, you know, What do you mean here, “Friend of the Devil”? The devil, quote unquote, in “Friend of the Devil” is a trickster. And the main character that Garcia sings the part of, the narrator of the song, accepts his kindness in “a cave up in the hills.” Which he later has to pay back. I think of Garcia himself as somewhat of a trickster, as were Kesey, Cassidy and the Grateful Dead phenomenon in general. And me as his friend.

GDB: You mention in the introduction that you have a whole shelf of books about the Dead that you haven't read. Maybe one of those is Rock Scully's book <>Living with the Dead? His book is kind of dark in parts – like Jerry being really high and flooding a hotel room; Jerry locking himself in an airplane bathroom for an entire flight to do his drugs. One of the things a reader might take away from Scully’s book is an impression of Jerry as a drug addict.

When I read your book and thought about Scully's book – it's about the same guy, but my impression of who that guy was is very different from each book. Do you think there were different Jerrys to different people? Like, was he a “drug addict” to some people in his life, but not to others?

LD’A: The theory has to fit all the facts. And it was hard to reconcile Jerry's. My gut when you ask that is that he was himself all the time.

I think the ultimate underlying cause of his substance problem was boredom. And I deduced this after seeing him in a lot of situations. As soon as something interesting happens, he loses interest in that other thing. So I thought, That's why I'm here. We're going to do some interesting shit. [When we were working on videos together] I tested it out a lot. He'd have his “works,” and he would go like this [Len mimes Jerry reaching for his “works”]. And then I'd say, “You know, we're talking about that scene with the car.” And it went for hours this way. I'm like, Well, couldn't be that strong urge if he can just put down the pipe.

He knew that people loved him. But you know, [Jerry’s attitude was] I'm gonna be me. In addition, there was no fear of death whatsoever. “You know, if you die, you won't see your children anymore.” “Yeah, I'm aware of that. What else can I say?” I mean he loved them, and he knew that they would be sad like all of us. But it’s like, Am I going to change my behavior because you'll be sad? No.

GDB: I don't want to dwell on his end, and we're going to back up to the beginning of your relationship with Jerry in a moment – but since you went there, I want to ask about his death. This was a guy who smoked a lot of cigarettes, who was overweight, who never did really much exercise.

LD’A: He had coronary heart disease his whole life. He didn't talk about it because he didn't complain ever about anything. Can you imagine that, a rock star not complaining?! You know, as opposed to, No red M&M's!

I learned a lot of things by writing this book because they're random memories that were written down at the time and then put away for 20 years – and then made sense of [when I put together the book]. He knew it was coming. I didn't know that he knew when we were together because I was probably in denial, which is a very powerful thing. But when I put the story together and then read it, I'm like, Oh…riiiiight.

[Shortly before Jerry died] he was talking about, “I went to visit Heather and Sarah, my first wife and first child.” I’m like, “Wow, how long has it been?” And he's like, “Forever.” That's the sort of thing people do when the end is nigh. And he could tell when he was smoking a cigarette that his cardio system wasn't working right.

GDB: Let's take it back now. It's 1980. Can you get into your mindset about what you thought about the Dead before you met them and were asked to work with them? Where were they in your world as far as your understanding or appreciation of their music, the scene, all that?

LD’A: I had filmed them many times but had never met them, because at the Capitol [Theater, in Passaic NJ], I was the house video person, or "vidiot," as we were called. And I was familiar with [the Dead’s] music. And I loved it. I had all their albums. But they weren't different, in my head, from the Beatles or the Stones.

I liked their music live. But – long shows, and you're working, and there was an opening act. It could be grueling because it’s live. You can't go, I'm gonna take a break. Lynyrd Skynyrd was the perfect act. They played 55 minutes. They did not stop. Whereas the Dead would stop, tune up for five minutes. That's their ethos. It's like, We're here to play, and you kids talk to each other for a while, you know?

But I did not meet them personally until 1980.

GDB: You started working with the Dead in late 1980. MTV launched in 1981, so the video era was moving past its dawn into full daylight. Some bands had recorded videos prior to that, and shows like SNL, Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert, and The Midnight Special in the 1970s gave audiences a chance to see their favorite bands on TV. Of course, prior to that there were appearances on Ed Sullivan, and movies like A Hard Day’s Night and all that Elvis stuff. And even The Grateful Dead Movie.

But then the Dead decide they want to do this livestream thing in all these movie theaters, something nobody’s done before. They hire you for the 1980 Halloween livestream from Radio City. And then later, you provided live video accompaniment for stadium shows. So, the Dead were, to some extent, in the vanguard of providing their fans with concert video experiences, both in-house and remotely.

Why was video livestreaming, and later on the in-concert reinforcement, a really good fit for the Dead? First, there’s the aspect of why the band was interested in it, what was their motivation?

LD’A: Number one, they were born by psychedelia.

GDB: Sure, if you go back to the early years, Grateful Dead were the house band for Kesey’s Acid Tests. And it wasn't about going to hear Grateful Dead music. It was about having an all-encompassing experience with all sorts of auditory and visual and other sensory exposure. It’s in their DNA. So doing a livestream broadcast of the 1980 Halloween show, and the live video reinforcement (like you did for their stadium tours starting in 1987) – all of that is, in a way, getting “outside the box” of what a concert experience was thought to be.

LD’A: Yes, and when this technology came along for stadiums, they literally said to me, “We want you to make it more like the Acid Tests. Something to look at that isn't us, you know?” And the video is meant to reach people who are literally a third of a mile away. People would give me shit about, This is about music, why do we have to have video? I'm like, Have you been to a stadium show?!

The other thing was that Garcia was as interested in film when he was young as he was in music and art. That's why the band is in the movie Petulia and why Garcia wanted to do the soundtrack to Antonioni's Zabriskie Point. Jerry wanted to be in movies, behind the camera and in front. He used being in a band to make movies. Can we sell some videos? Yeah, let's do that.

GDB: You write about how he never skimped on quality when it came to the projects you were involved in. Like the video equipment for live show projection.

LD’A: He says, “Is this the highest quality video we can get?” And I'm like, “No, this is reinforcement. Why would you want better than that?” He says, “We want the best. We always want the best of everything. Do you understand?” I didn't have the guts to say I didn’t quite understand why. I know now, because all these shows were sold later on, after he died. The band subsisted on them! They made millions from each different DVD. We put out about ten of them.

GDB: What was it like planning for those live stadium shows with on-screen projection shows? What did the band want from you?

LD’A: They would say, “Yeah, we don't want to be the center of attention because we don't do anything. We want to entertain the crowd. What can you do?” And I'm like, “Sure, we could do all kinds of effects.” Then I heard from people who believe that the Dead are just music, they weren’t happy when video reinforcement came to the Dead, so they said we can't have pictures. But it was Garcia who was in charge, the band put him in charge of visuals. He would say, “I'll cover this. I know about movies, and Len, you'll answer to me. I'll take care of these guys.”

It got expensive, and my job as a producer and director is to minimize my client’s expense. So I'd have to remind them: “This is going to cost you a shitload, and I don't see how you're going to get that money back.” They're like, “Len, it's not your problem.”

GDB: So you're off the hook, and you get to spend the money.

LD’A: Right. And also, the effects evolved rapidly between ‘87 and ‘91. So each year it got more “out there.”

GDB: Let’s talk about your friendship with Garcia. You wrote in the book about a couple of “fanboy” moments that were embarrassing to you, like when you got to hold one of Jerry’s guitars. You didn’t want Jerry to think you were just another Deadhead hanger-on, and it doesn’t seem like that was the case. But was there always a little bit of rock-star-and-employee energy in the air? How did that evolve?

LD’A: He was an anti-rock-star, and he meant it to the core. I never saw him hesitate from that stance. He did any interview, he would talk to anybody. He insisted on being who he was. [Being considered a rock star] was painful for him, and painful to witness. I would get nowhere if I didn't be me and let him be him.

Jerry was a shaman, let's face it. Keith Richards is a shaman. These people are summoning the gods and the beasts, and you're getting fucking high on it. And it's fantastic. But they’re just people. And [Garcia] was aware of that. He has five daughters. I got to the very end of the book before I said the quote about, “If you think I'm God, you should talk to my children.”

[One time] I visited him when he was practicing. I was like, Whoa! I looked at the sheets in front of him and I said, “32nd notes?!” He goes, “Yeah.” And I'm like, “How much do you do this?” And he's like, “Every day.” Then he said, “You think it's easy what I do? I got to do this, or I get out of shape.”

GDB: I liked reading about you, Jerry, and hotel operator Bill Kimpton, in Jerry’s last year or so, having serious discussions about opening a small venue in San Francisco called Café Garcia. The idea was, among other things, that Jerry could play intimate sets anytime he wanted without being tied to tour dates, set times, etc. He could just drop in and be Jerry the guitar player, not Jerry the rock star. A lot of the vision you describe in the book has similarities to what Phil intended with Terrapin Crossroads [TXR]. Did you ever go to TXR? How would you compare TXR with what you thought Cafe Garcia was destined to be?

LD’A: Jerry’s idea was much smaller. He said, “I'd like a place like places I played when I was a kid. A coffee house. No booze. Just coffee and wine and open mic. And we'll call it Cafe Garcia.” Perfect. “Yeah, I could just hop in the car and drive to my place and play whenever I felt like it. All I need is my guitar.” The capacity would probably have been a couple of hundred people.

Café Garcia wasn't designed to make money, as nothing Jerry did was. It was designed for him to have fun. And when you're having fun, you just generate a shitload of money – if you're Jerry Garcia. He once said, “I'm gonna actually just put out a tape of me farting. I could sell a hundred thousand.”

GDB: Can you imagine if he did that? There would be cover bands now doing Jerry’s farts. What's your take on this whole phenomenon that really, in many ways, exceeds the legacy of possibly any other band? I'm sure there's no band in history that has had as many cover bands. Places like the Greek Theater in Berkeley and the Capital Theater in New York sell out shows with a note-for-note gig like Dark Star Orchestra, and also for a complete reinterpretation band like Joe Russo’s Almost Dead. Not to mention all these incarnations of bands with the members of the Dead post-Jerry, both together and separately. Phil [Lesh] has probably played in 250 or way more unique lineups with Phil & Friends and all those TXR shows. And then there’s the Dead & Co. Sphere residency.

I also think it’s a certainty that more lifelong marriages and partnerships sprung from the world of Grateful Dead than any band in history. [As it turns out, Len and I both met our wives at Dead shows.] How is it that it outlived Jerry, who was clearly the focal point?

LD’A: Seeing Dead & Co. at the Sphere, I was crying. I just couldn't believe it. It was just overwhelming. It's so beautiful. I started my professional career with black and white, one camera. And to see the apotheosis of video at the Sphere is just – there's no more. You don't show the band anymore. The technology itself now offers such amazing beauty.

[But] they'll come back when Bobby's gone too. It's the songs. It's spirituality that people feel together at these events, and it doesn't matter who's playing them, as long as they do a good job.

Why do people love this guy? I don't know if I succeeded at all in explaining why. But I did my best, I think. But the argument of who was he really? Now we're in “Citizen Kane” territory. Different sides to the same story. All true to the storytellers, but irreconcilable to people who hear the different versions.

I go back to the intellect, the mind. Somebody who's that wise and that learned and articulate is going to be seen by different people in different lights, and that's just fine. If somebody says, I was there when that happened, Len, and you got it wrong. I'm like, fine, write a book about it.