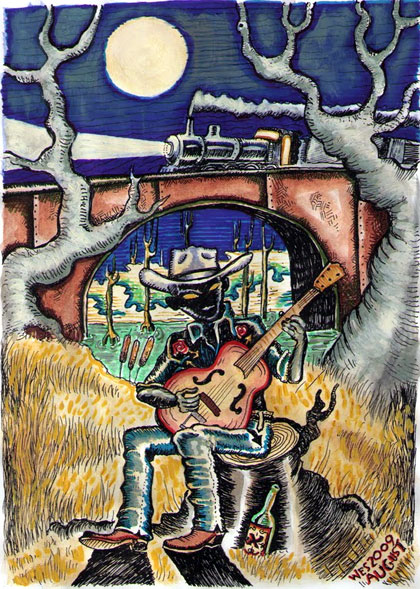

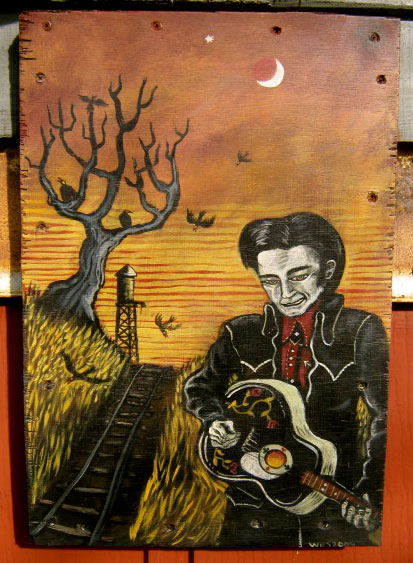

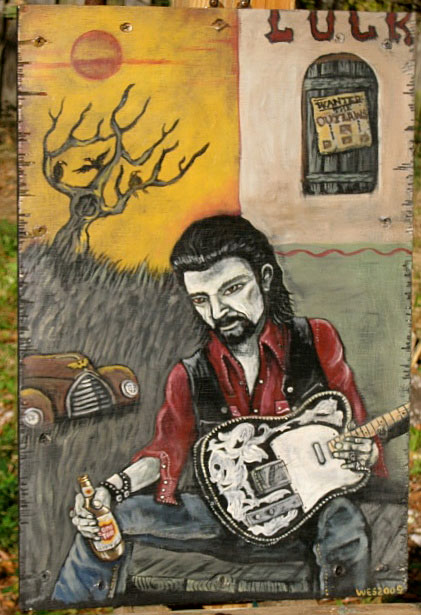

Visual artist, writer, musician and actor Wes Freed is a Southern Gothic multi-disciplinary wonder of sorts. His work overlaps to such an extent he almost sings his paintings and paints his songs. Freed himself, his wife and long-time collaborator Jyl, his truck and his home studio all seem to overlap with it as well. All are best described as looking like live people, places and things from Crow Holler, the setting for most of his work.

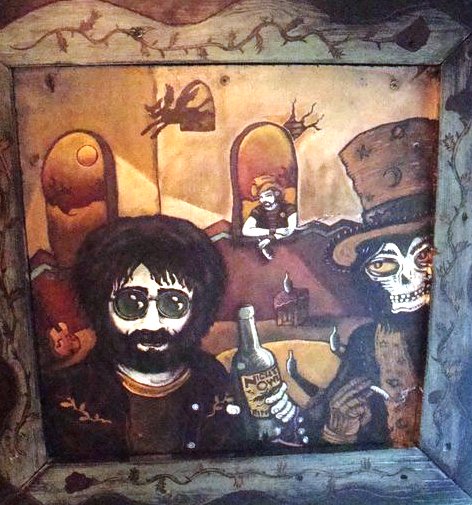

Crow Holler is a world built from memory and memory of memory. In all of the forms Freed's art takes, its' corners and crevices are exposed, piece by piece. As this occurs, an anticipatory peace emerges. A one-eyed owl hovers on the edge of an eerie landscape. Withered trees scratch a lonesome Moon. You have the sense, as you look and listen, that something surprising is just around the corner. Smiling sirens beckon, hint that you should come closer; their moon-round eyes all aglow. Faceless men linger on lonesome roads, creep out of dark caverns, waiting, expecting.

You feel they look back at you. Their expressions have an effect similar to that of Goya’s portraits; their glances suggest secrets, possibly profound ones. Here, a pipe-smoking skeleton grins, leans in to tell an ancient tale. There, women with their souls in their eyes wait for you with half-hidden smiles. The images and words that emerge from Freed's inner world are haunting. Once you have seen and heard Dixie Butcher, Cecil Lone Eye, the Conjure Man or any of the other Crow Holler folk, you find you can leave them for as long you like but neither they nor the place quite leaves you.

It's familiar, comfortable but also foreboding. Some of the people and places are just shadows. Some are skeletal. Others burst with life. “We've found it! Come in! Come see! Here! It's right over here!”, the people and creatures who live there all seem to say. You feel the “It” they speak of is something you’ll recognize the second you see it. “It” is something you wanted so badly you hid it far, far way long ago. “It” vanished in the material world but hasn’t gone away here. No, in Crow Holler you find it again, tucked in a corner of the world of dreams where it’s almost always autumn. There air is thick with the odor of hay and spilled gasoline.

Crow Holler is, in part, a re-creation of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, where Freed spent his childhood. He described it as a place, "full of old dirt roads, straggling trees on hillsides; corroded by time and progress.” He left the Valley for Richmond's Virginia Commonwealth University, where he received a degree in painting and printmaking.

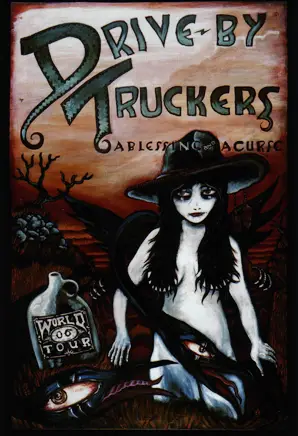

Like Chagall, he never returned to the place that his work often reflects wistfully but his memories permeate his work. Best known for his album and poster art for the Drive-by Truckers, Wes Freed is not only a visual artist and actor, (cult classics, 'Thrillbillies' and 'Degenerates Ink', both written for Wes and directed by Jim Stramel), but he's a singer/songwriter as well with a new band, The Magnificent Bastards. He talked with me about his film, art and music in a series of conversations a while back.

GW: I asked him first about his films, 'Thrillbillies' and 'Degenerates Ink', were the parts really written for him?

WF: In the first film, ('Thrillbillies') we're heroes, killing to 'take back the South' and in the second we're anti-heroes. Most of the people we kill are guilty of nothing but being obnoxious -- we're tattoo artists but it becomes easier killing people and taking money than it is making money for tattoos.

WF: Jim wrote Thrillbillies with the three of us in mind, yes. I'd never acted before nor wanted to had never had that much interest in pursuing it, though playing music is kind of like acting; you have to personable and hold attention.

WF: Anyway, in 'Thrillbillies', the lead role was originally planned for a man, but our actor opted out a few weeks before shooting so we asked Erin, who played fiddle for Jyl, (Wes' equally talented wife), and my band The Shiners. We decided not to change anything, even though she was female, just have her play it very mean and butch.

GW: What, I asked him, about his music?

WF: It's more of a continuation of the music I was doing before with Dirtball and The Shiners, though this time I'm writing more. In fact, I've written almost all of the songs we're recording now. It all fits into Crow Holler, (the location of his paintings). It's not old timey, it's not really not modern... they're just written in a way that they could exist in any time really.

WF: The songs, like the paintings, deal with moonshine, ghosts, lonesome roads... there's a tavern song written from the vantage point of a dangerous man before he got all big and dangerous, when he was a bum out roaming around not having any place to call home, living on the road... one I wrote about moonshine while watching 'The Sopranos', about how the moonshine industry is a family sort of thing and nobody talks out of turn or you just disappear somewhere in the swamp... it is kind of like 'The Sopranos', when a brother turns rat, no questions asked, just an empty spot in the pew Sunday morning. It's the dark side of things but it's an explanation of why it is what it is.

WF: The songs, like the paintings, deal with moonshine, ghosts, lonesome roads... there's a tavern song written from the vantage point of a dangerous man before he got all big and dangerous, when he was a bum out roaming around not having any place to call home, living on the road... one I wrote about moonshine while watching 'The Sopranos', about how the moonshine industry is a family sort of thing and nobody talks out of turn or you just disappear somewhere in the swamp... it is kind of like 'The Sopranos', when a brother turns rat, no questions asked, just an empty spot in the pew Sunday morning. It's the dark side of things but it's an explanation of why it is what it is.

GW: What sort of music do you listen to?

WF: I listen to a lot of Dead, which depends on my mood. Workingman's Dead and American Beauty are in heavy rotation -- I love High Time, Loser, Cracker does a great cover of that... I've been hearin' Sugaree in my head a lot lately. I really like the Country feel of some of their tunes. And I love their song structure, I'm drawn to more structured songs as a general rule.

WF: When I'm in the truck I listen to the outlaw country station... otherwise it depends on the time of year or what I'm doing. I like Hank Sr., Stranglers, Gun Club, Holy Modal Rounders, Robert Johnson, Lightnin' Hopkins, Willie Nelson... I was a member of the Willie Nelson fan club in 1977 or 1979 or so", he laughed. "I don't remember when I stopped paying my dues but that card was in the wallet I carried around in elementary school. I had Confederate money and my Willie Nelson fan club card in there. he continued,

WF: We had so much Confederate money - a box of it - -that had been left over because it became useless in about 1863. What we had would probably have been enough to buy a loaf of bread in 1865. The Confederate money in my Grandfather's wallet was like buying stuff in pesos or lyre.

GW: Along a similar vein, I asked, what movies do you like to watch?

WF: I love 'Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid', the Sergio Leonne movie, 'Dusk till Dawn, all of Quinten Tarintino's stuff, most of Robert Rodrigeuz stuff... I really love old '50s black and white flying saucer and giant insect movies and early '60s them and The Thing from Outer Space, the original, although the John Carpenter re-make with Kurt Russell was pretty good. Movies have probably influenced my song-writing as much as listening to other music has. I write in a very visual style; I tend to think in images and write out the images --

GW: You're best known for you album art... what album art struck you when you were younger?

WF: I always liked the Dead's album covers. When I was a kid I loved the Kiss album covers, I liked Destroyer and Love Gun the best not Rock and Roll All Night, though I like that one better now. My taste has changed as I've gotten older (laughter).

GW: What, I asked him, did you want to be when you grew up?

GW: What, I asked him, did you want to be when you grew up?

WF: I think this is it. I wanted to be doing what I'm doing. In my fantasies as a kid there was a lot more money involved (laughter). I think I probably figured when majored in art that it wouldn't matter what I did with it because I was going to be a rock star anyway. I figured I could fall back on being a starving artist if didn't make it as starving musician.

WF: I was initially going to major in commercial art and, when I was younger, I used to imagine ending up like Darren Stevens. I thought I'd walk around with a portfolio and people would ask me to draw things and they'd pay me for it, like he did. I figured I could do that.

WF: I would have never told Elizabeth Montgomery she couldn't use her magic powers. I think that was really short sighted of Darren. Reigning it in some kind of makes sense, that much magic could've taken a lot of the challenge out of life. But man, to have wasted all that potential!

WF: Anyway, initially I was going to go through the commercial art program but halfway through the art program you have to learn painting. You learn it in a way that, if you stayed in commercial art you'd never use again. It's a really good thing, it shows you where you want to go. Well, I saw that what I wanted to do was go into painting. To be quite honest, I never really thought about where it was going to lead; I just went from situation to situation and hoped for the best.

Wes Freed’s paintings, like his film roles, (Jim Strammels’ “Thrillbillies” and the soon to be released, “Degenerates”), can be savage, extreme, imperative. His songs are no less intense, though by contrast, quietly fierce. He communicates, through all of these mediums, a one-man universe full of stark dualities that are uniquely Southern. It is not the South you are accustomed to seeing, not one you expect to see. He exposes the dark, gritty underside of all that, both good and bad equally. The omnipresent possibility of both permeates his strange, sparse landscapes.

“To me”, Freed said when I asked him what the ominous tone that crept into his work was reflective of in a recent interview, “ominous isn’t really bad, it means something interesting is going to happen.”

His memories are layered with those of his Grandfather who in turn, was layering stories his Great-Great Uncles told him as a child. I asked him to tell me more about them.

WF: My Grandfather’s Uncles filled his head with stories and he filled mine with them and some more of his own. When you’re a little kid you believe everything adult’s say. They’ve blended together in my mind, formed a backdrop (laughter).

WF: My brother and I spent a lot of time with my Grandfather. We lived on the same farm and he was just a walk down a dirt road away. He had a ‘51 Ford pick-up, open on both ends, that we'd sit in. He parked it in his corn crib to keep it out of the rain. We'd play with our jack knives while he told us stories.

WF: That truck is almost a shrine now, still full of the things that were in it the day he died, like an old corn shucker with “The Boss” engraved on the bottom, Lucky and Camel packs, receipts going back to before I was born. I used to go sit in it every day and pretend I was driving (laughter). One day, the truck disappeared. I asked my parents what happened to it and they suggested I call the Sheriff, he laughed again, turned out they’d gotten it running for me for my birthday. They forgot to flush the radiator though; it never drove right after that.

WF: That truck is almost a shrine now, still full of the things that were in it the day he died, like an old corn shucker with “The Boss” engraved on the bottom, Lucky and Camel packs, receipts going back to before I was born. I used to go sit in it every day and pretend I was driving (laughter). One day, the truck disappeared. I asked my parents what happened to it and they suggested I call the Sheriff, he laughed again, turned out they’d gotten it running for me for my birthday. They forgot to flush the radiator though; it never drove right after that.

There are not only Southern but also outlaw undertones to Freed's work. These may center most strongly on tales of a Confederate General named Mosby. His Grandfather's Uncle's, who had been Calvarymen with him in the War, painted tales of him that match the devil-may care spirit of much of Freed's work.

WF: Mosby did a lot behind the lines (laughter) he and his men also robbed trains. Some of the men were hung in a public square with a note on them that read, “This will be fate of Mosby and all his men. They weren’t outlaws; they were all sanctioned but were spies and guerillas.”

WF: It’s such an intangible thing, communicating the whole idea of the War, Mosby, the Valley. It’s just a feeling for me, something personal that would be hard for someone else to understand because it’s so much a part of what’s going on in my brain. It’s like when I was eight and had this buzzing in my head after I’d taken some Robitussin for a cold. It’s just a feeling. There’s smells, sounds, sights; the smell of the truck and the corn drying in the cribs, the barn.

The nostalgic wistfulness of his work is not unlike that seen in the paintings of Bruegel but with darker undertones. It's as though we're looking at the phantoms of lost dreams. In a sense we are. The places and times he draws from are irretrievably gone.

WF: Bruegel was painting a vanishing culture. His landscapes weren’t completely romanticized but you get the feeling that he loved the farms that he drew. My paintings are in some ways are similar, like a memory.

Also like Bruegel, Freed sometimes brings out chimeras from a gallery of oddities that's often a little sinister, frightening. They lend a supernatural quality to his work, which has a touch of the Danse Macabre to it as well. Skeletons often dance in Crow Holler and other ancient rituals unfold. Unlike traditional Danse Macabre paintings, the common themes of remorse, hysteria, hopelessness, the grave, are absent. There is a common sense of mystery, however, of both profound contentment and wild abandon.

GW: I asked Freed if the idealized dream of lost happiness spread across an often ominous, spooky landscape didn't seem like a contradiction to him.

WF: Both the dark and light of it are reassuring to me. Beautiful is a subjective term. I see it as a paradise. When I was a kid, the idea of the Sunday school version of Heaven scared the Hell out of me. No dead trees? No old cars? No rust or broke down old barns? That didn't sound like Paradise to me.

WF: Both the dark and light of it are reassuring to me. Beautiful is a subjective term. I see it as a paradise. When I was a kid, the idea of the Sunday school version of Heaven scared the Hell out of me. No dead trees? No old cars? No rust or broke down old barns? That didn't sound like Paradise to me.

GW: What would you find in Paradise?

WF: A beat up old garage with a cool car and a bunch of motorcycles; a place where it wouldn’t rain a lot but it would be cloudy a lot and the temperature would be just right. It would be full of the smell of baking chicken, gas and motor oil, things like that. Paradise isn’t really planned out. Crow Holler is almost like a dream state, like that half awake place you go to when you’re a kid.

WF: In the winter, my Grandmother cooked on a wood stove and my Grandfather had a rocking chair that sat next to it. There was a set of steps that went up the back way to what used to be my Dad’s bedroom. We’d sit on the steps and look out the window while she cooked. In that sort of setting, you can romanticize just about anything. That setting, to me, is part of Paradise; full of the smell of a wood stove and whatever's cooking; with Grandma downstairs plucking a chicken.

WF: I think with my art I’m mostly trying to convince myself that the place really does exist somewhere. Maybe I’ll find it, in a metaphysical sort of way...

In Freed’s work, fantastic imagery is used to create a dream world that mirrors our own. The monsters, chimeras and bizarre fantasies that come to life in Crow Holler are visual metaphors, a private language of symbols. As with Bosch's, the paintings lead the viewer to question the conflicting qualities encountered there. Sometimes this leads us to question the ones we encounter within.