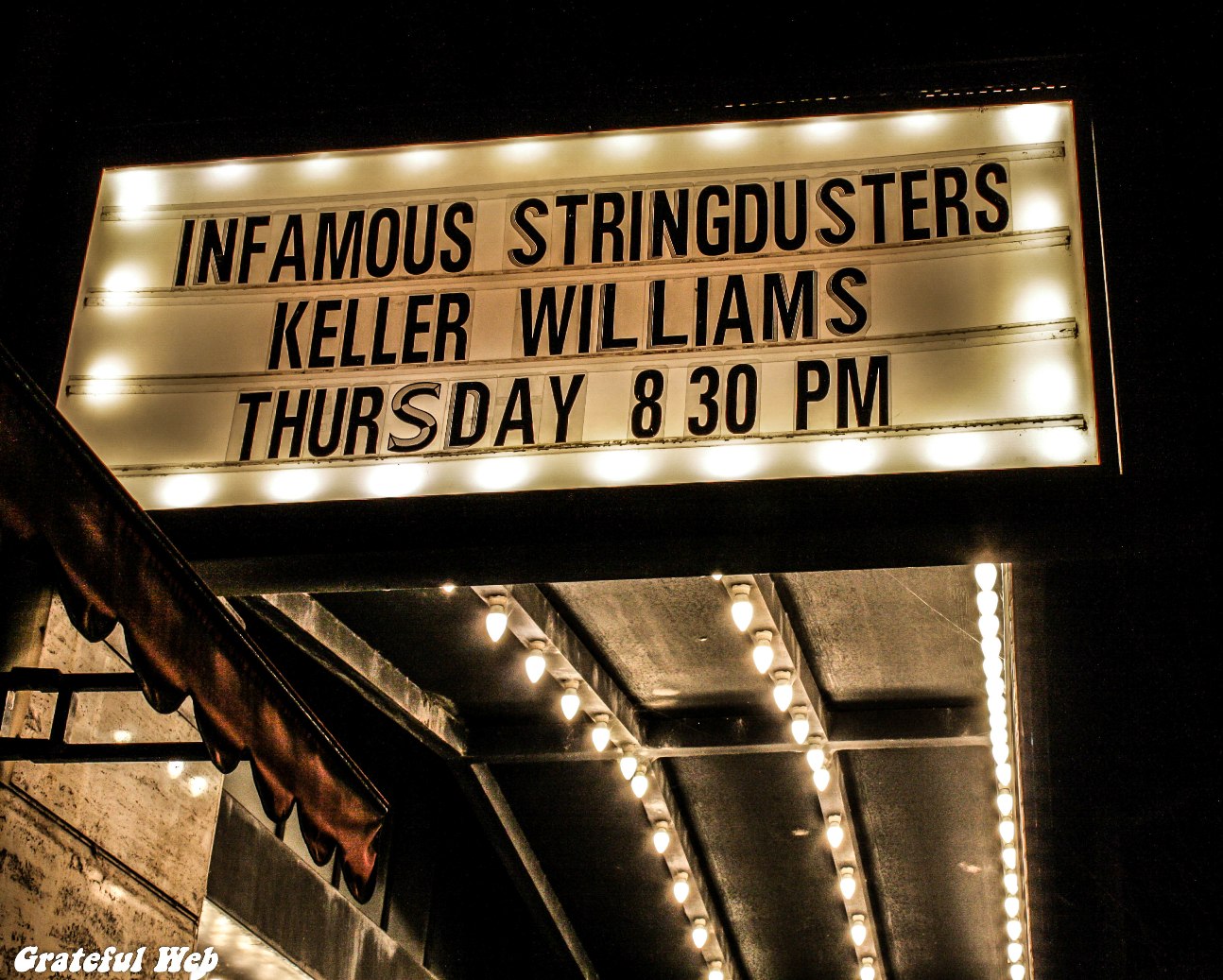

The Infamous Stringdusters put the spurs to their spring tour with a fret-blazing, shape-shifting show featuring special guest Keller Williams at Eugene’s McDonald Theatre (March 5th). The ‘Dusters delivered a convincing account of their distinctive “high country” sound while Williams complimented nicely, both with an impressive opening set and later, playing alongside the headliners. The pairing made for an entertaining combination of Nashville polish and free-spirited, festival charm.

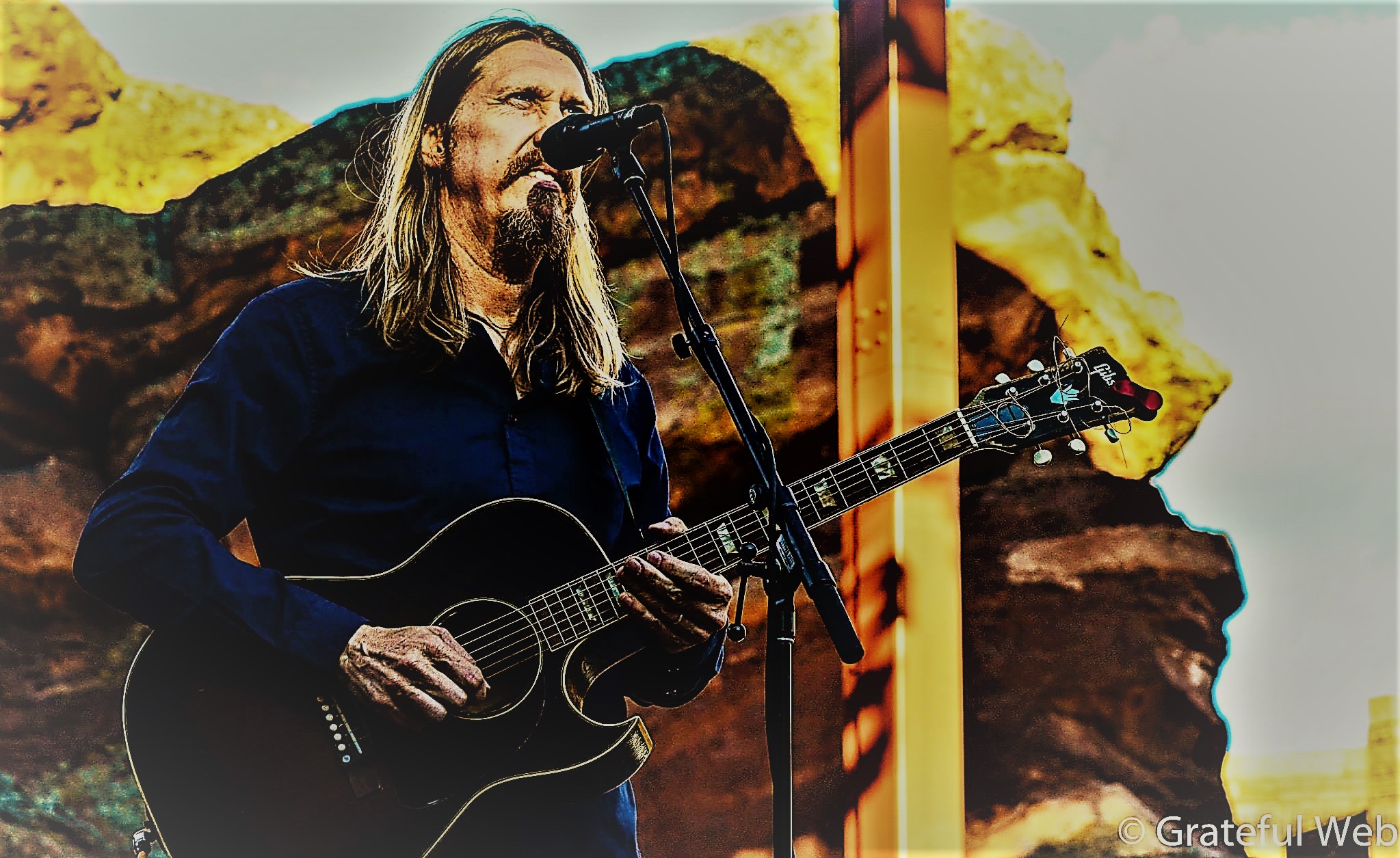

Williams took the stage without introduction and quietly went to work. His unannounced presence melted into the vibrant pre-show buzz, shifting the mulling patrons’ attentions and coaxing them toward his increasingly enveloping song.

KW satisfied right from the start, producing an opening suite of songs that included the rhythmic pluck and strum of “Thin Mint” followed by a riveting, Indian-flavored, Beatlesque trip-out, “Breathe,” and then the angular, thumping strut of “Cadillac.”

The latter tune, recorded with Bob Weir for Williams’ album Dream (2007), conveyed the unmistakably crooked gait of a “Bobby song.” A highway spiritual (of sorts) with a funky, churning rhythm, “Cadillac” had the crowd gently cruising.

Proficient on multiple instruments, Williams is primarily a guitarist who makes significant use of a technique invented (or at least popularized) by Les Paul—phase looping. Williams plays, captures and loops musical lines, essentially recreating multi-track recording capabilities in a live setting. This enables him to (no pun intended) play with himself. These layers of musical ideas form a kind of psychedelic, folk-rock sound system.

Williams’ meaty (hour plus) set was full of enjoyable highlights. His comical, reefer folk-tale, “Doobie in My Pocket,” was unsurprisingly well-received by the enthusiastic Eugene crowd. He turned his Virginia drawl loose on a beautiful cover of Mandolin Orange’s “Waltz about Whiskey.” But, the powerhouse (20+ minute) combination of “Best Feeling>Song for Fela” really put some kick in the kettle.

Williams made great use of the phase looping effect on “Best Feeling,” mixing a bouncy, calypso guitar riff, a bumping bass line and an electronic drum-beat into a breezy, Jack Johnson-style jam. The song stretched as Williams improvised effects-laden flourishes over the repeating patterns, and eventually found “Fela.”

A tribute to the “Godfather of Afrobeat,” Fela Kuti, “Song for Fela” is a fierce polyrhythmic cook-out that tested the known limits of sound produced by a single human being. The thick, double-wide groove culminated with KW duplicating and stacking his own chanting voice into a strange, clone choir. The pulsating rhythmic intensity suggested another of Kuti’s disciples, Talking Heads, as well as the track’s Nigerian namesake.

KW’s congenial hippie vibe was infectious and his outstanding opening set had everyone feeling groovy. Williams has elevated the practice of busking on Dead tours to an engaging, entertaining art-form. His symphonic, one-man, minstrel act provided the perfect stage-setter for the Infamous Stringdusters’ dynamic ensemble play.

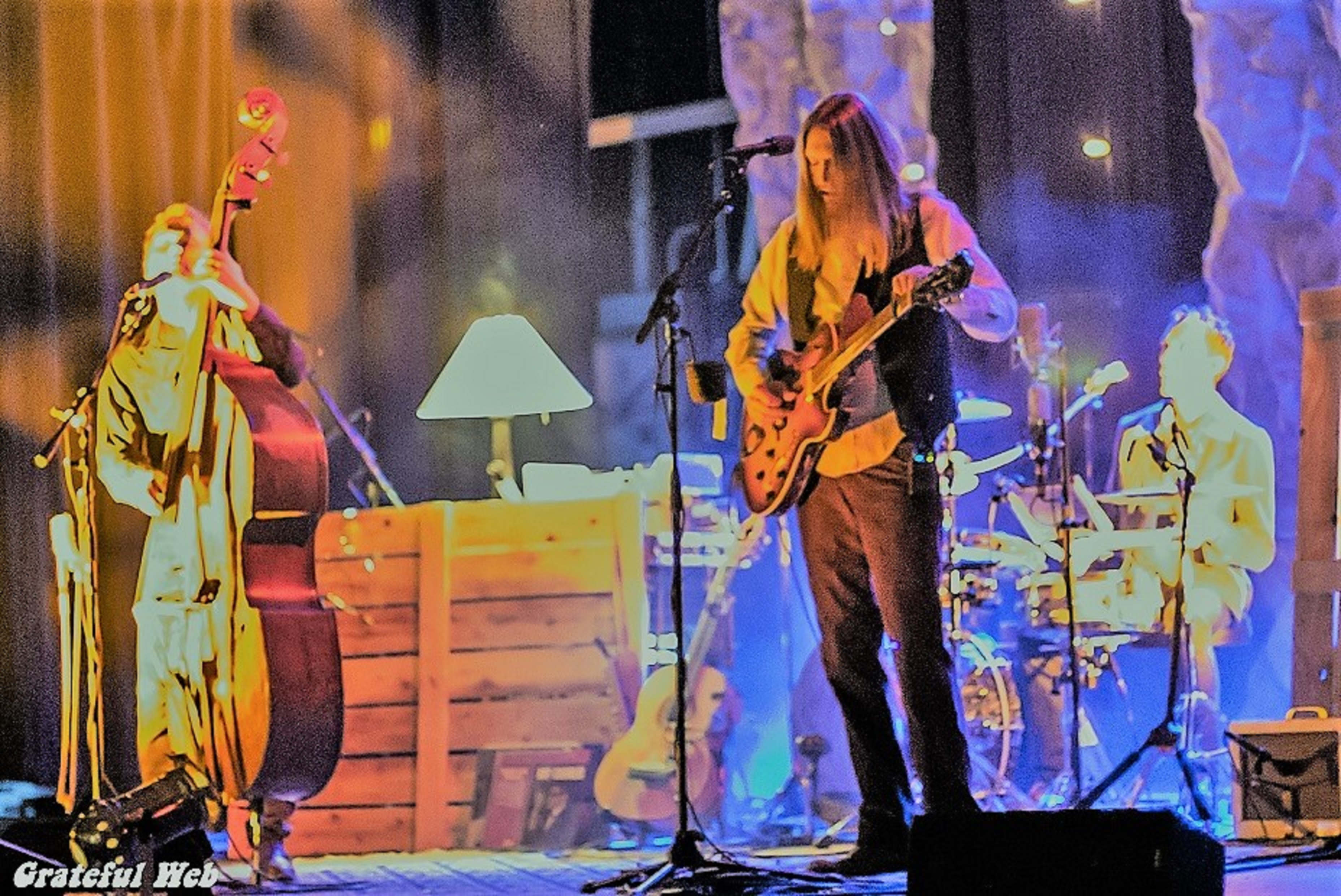

The ‘Dusters energetically strode to the stage looking well-rested and excited to be playing in front of people again. They immediately slid into a sweet, slippery instrumental breakdown that served as the introduction to a jubilant, “Mountain Town.”

A stunning demonstration of the band’s mastery of synchronized tempo, “Mountain Town” climbed steadily, coasted for a bit, and then throttled all engines furiously ahead. Showing no signs of rust, the Infamous Stringdusters instead gave straight-forward notice—this “New Grass,” country outfit can rock a little too.

Right from the outset, the ‘Dusters asserted their “expansionist” take on bluegrass and country traditions. “Peace of Mind,” from the band’s most recent release, Let It Go, had a swampy, backwoods quality, punctuated effectively by fiddle player Jeremy Garrett. It sounded almost country, yet owed just as much to folk and Southern rock influences.

A rip-roaring cover of John Hartford’s “Steam Powered Aeroplane” was cooler than a high mountain stream. While ringing with traditional country overtones, “Aeroplane” sailed with a buoyant energy that defied any categorization beyond “real hoot.” The song featured some fine Dobro work from Andy Hall, and was carried over the top by upright bassist Travis Book’s exceptionally colorful vocal turn.

After this piping hot, three-song “How Do You Do?” the band paused to warmly acknowledge the appreciative Eugene audience, as well as “the Master of Ceremonies,” Keller Williams, and to dedicate the ensuing song, “The Hitchhiker,” to those thumbing their way to the next show.

“The Hitchhiker” is one of the ‘Dusters signature tunes, showcasing their ability to reconfigure traditional musical styles and infuse them with fresh, uniquely characteristic ideas of their own. At the McDonald, the song jangled and whined at first, like an eerie, bluegrass death dirge. More defiant than sorrowful, it leapt off and glowed; an echo of an original template consumed and resurrected with new, multi-faceted significance.

The Stringdusters executed a classic jam-band curve, transforming “The Hitchhiker” from something recognizable—a Jim Lauderdale-style, bluegrass boogie—into something infinitely more difficult to define. The band’s newest member, guitarist Andy Falco, enthusiastically explored this added dimension in an amazingly fluid solo coursing with cosmic assertions.

The ‘Dusters offer a modern take on the traditional bluegrass “breakdown,” incorporating improvisational jazz and the Grateful Dead. “The Hitchhiker” typified the band’s reputation as “expansionists.”

The sprawling, feature-length, Western gunslinger, “Tragic Life” further illustrated the ‘Dusters propensity for stretching out. The epic outlaw tale featured terrific instrumental turns from Garrett, Hall and Falco, but banjo-player Chris Pandolfi’s meandering stroll on the prairie was particularly gripping.

Pandolfi has fashioned a unique style which admirably doesn’t sound anything like the giant of bluegrass banjo, Earl Scruggs. His technique is more deliberately paced and favors lingering a little over individual notes rather than rapid, Scruggsian rolls. A former student at Berklee College of Music, Pandolfi’s learned vocabulary enables him to convey a wide spectrum of ideas. His creative approach sounds less “hillbilly” and more “Music Appreciation.” Panda’s inventive banjo is a fundamental element of the band’s appeal, and his contributions in Eugene greatly enhanced songs like “Tragic Life,” “High Country Funk,” and the beautifully rendered “Machines.”

“Machines” was a masterpiece of instrumental interplay weaving intense, individual strands of ingenuity into an exquisite tapestry of a song. Each member led captivating excursions to the “high country,” freely chasing variations from the hollows to the hills.

The Stringdusters eventually got back to basics with a series of choice covers. Restating the central pervasive core of their musical vision, they first performed a heartwarming version of Lester Flatt’s “Head over Heels.” Next, they slipped into the old-time murder ballad, “Frankie and Johnny,” with an arrangement that recalled the “Singing Brakeman,” Jimmie Rodgers. Their “Travelin’ Teardrop Blues” fell somewhere between Shawn Camp’s Nashville yearning and Del McCoury’s “High Lonesome” howl. The ‘Dusters embraced the song’s restless lyric and knowingly captured both the anguish and the enlightenment of the road.

Shifting positions onstage in a succession of quick moves, showcasing various combinations of slick picking, fiddling and harmonizing, the Infamous Stringdusters reestablished their barnstorming bluegrass roots.

They concluded their exceptionally well-played, highly entertaining set by inviting Keller Williams to join them for the last few songs. “There is a Mountain” was the shiny nugget of this final sequence. Easing in on Garrett’s fiddle and Book’s bass, the song found a folksy, vaguely spiritual voice that beautifully expressed the band’s transformative nature—“The caterpillar sheds its skin/to find the butterfly within.”

Keller’s song, “Gallivanting” celebrated weirdness and oozed an electric Kool-aid, Prankster vibe. A few of the ‘Dusters dove into the deep water and stroked, but Pandolfi plucked a jazz dripping solo on his banjo that simply walked to the other side. Throughout the set, Panda demonstrated remarkable range and originality on this fairly type-cast instrument.

An exuberant “Scarlet Begonias” provided a fitting end. The Grateful Dead didn’t invent the “Doors of Perception,” but they introduced them to a lot of people in the room. They also gave these artists ideas about how to activate them within their music. In many ways, both patrons and performers resembled “Jerry’s kids,” singing a tireless song—“Everybody’s playing in the heart of gold band.”

The Infamous Stringdusters come from a different place than Bill Monroe or the Stanley Brothers, and you can undoubtedly hear that distinction in their sound. The specific, shared sense of (spiritual) place and experience found in traditional bluegrass is harder to locate in the Stringdusters’ songs. (Ironically, someone in the crowd held up a sign at one point that said, “Play more Gospel.”) The ‘Dusters seem to be constructing their own myths. They are performing many generations removed from the height of “High Lonesome.” They utilize traditional instrumentation, but their intelligent arrangements place these signature tropes in unconventional contexts. The Infamous Stringdusters are making new use of bluegrass music, rather than simply recreating it. The result at the McDonald was inspired, appealing and a first-rate blast.