Veteran midwestern rockers, Umphrey’s McGee returned to Eugene (Ore.) for the first time in five years and unleashed a torrent of heavy, metallic, guitar-driven jams on a packed, Friday night crowd at the McDonald Theater. Combining a taste for crunching, head-banging riffs with mind-melting prog-rock fusion, Umphrey’s are an intriguing musical complexity. Their two thick sets at the McDonald shook the skulls of the hyped, responsive audience and delivered a dizzying array of intense, heady sounds.

Umphrey’s concerts, and even their individual songs are like guided tours of their impressive record collections. UM’s alchemy occurs in the strange mash-ups of styles their imaginative improvisations produce. Fierce, cerebral rock reminiscent of Yes, King Crimson or Frank Zappa mingles with sweaty, British Steel like Motorhead, Iron Maiden or Judas Priest. Extraordinary fusion guitar jams akin to Jeff Beck or John McLaughlin shift suddenly into flashy, Van Halen-styled arena rock. Elements of noise, techno, free jazz, funk, classical and dub are also all apparent in Umphrey’s striking eclecticism. UM’s performance at the McDonald rendered a virtuosic sample of their blistering rock pastiche.

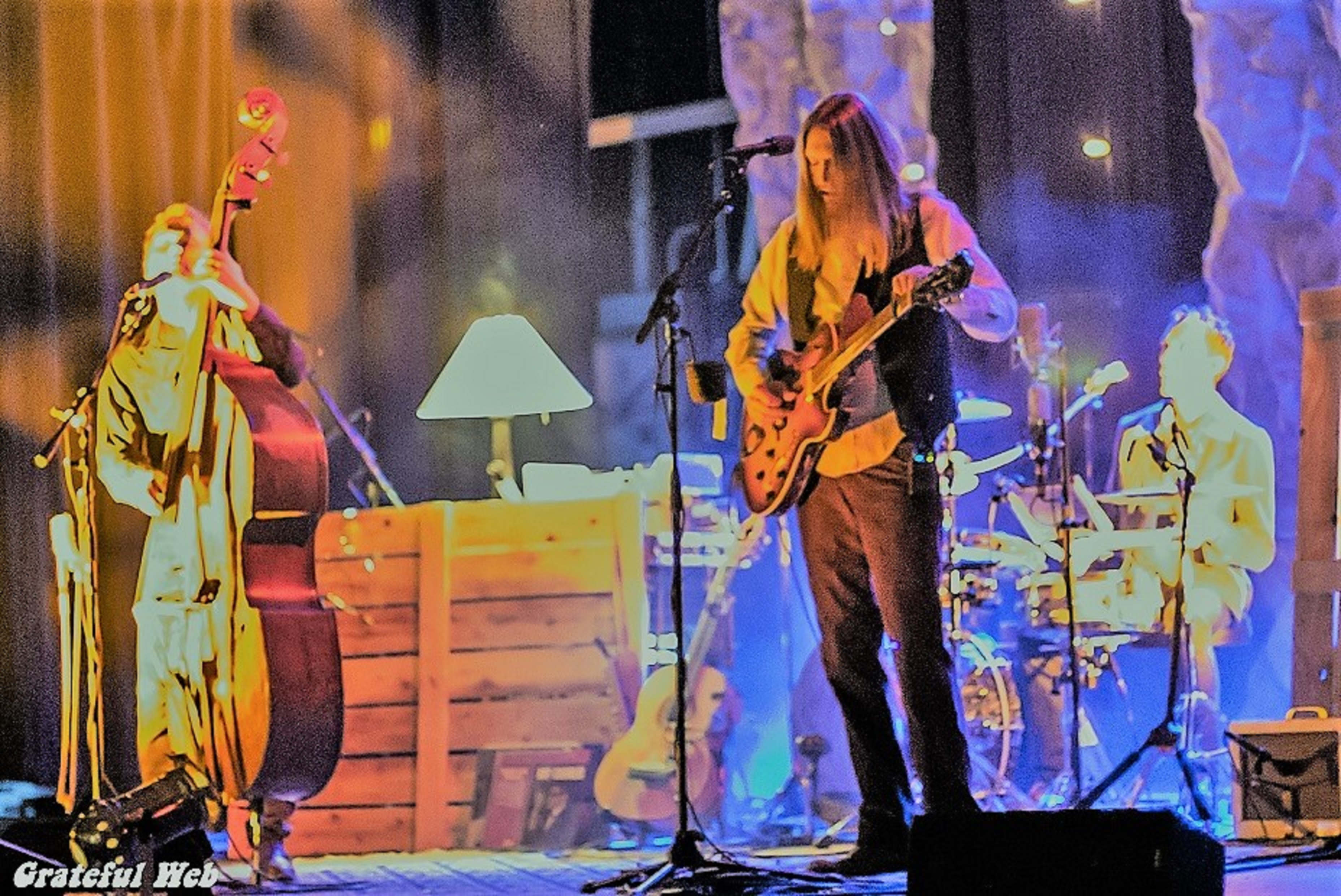

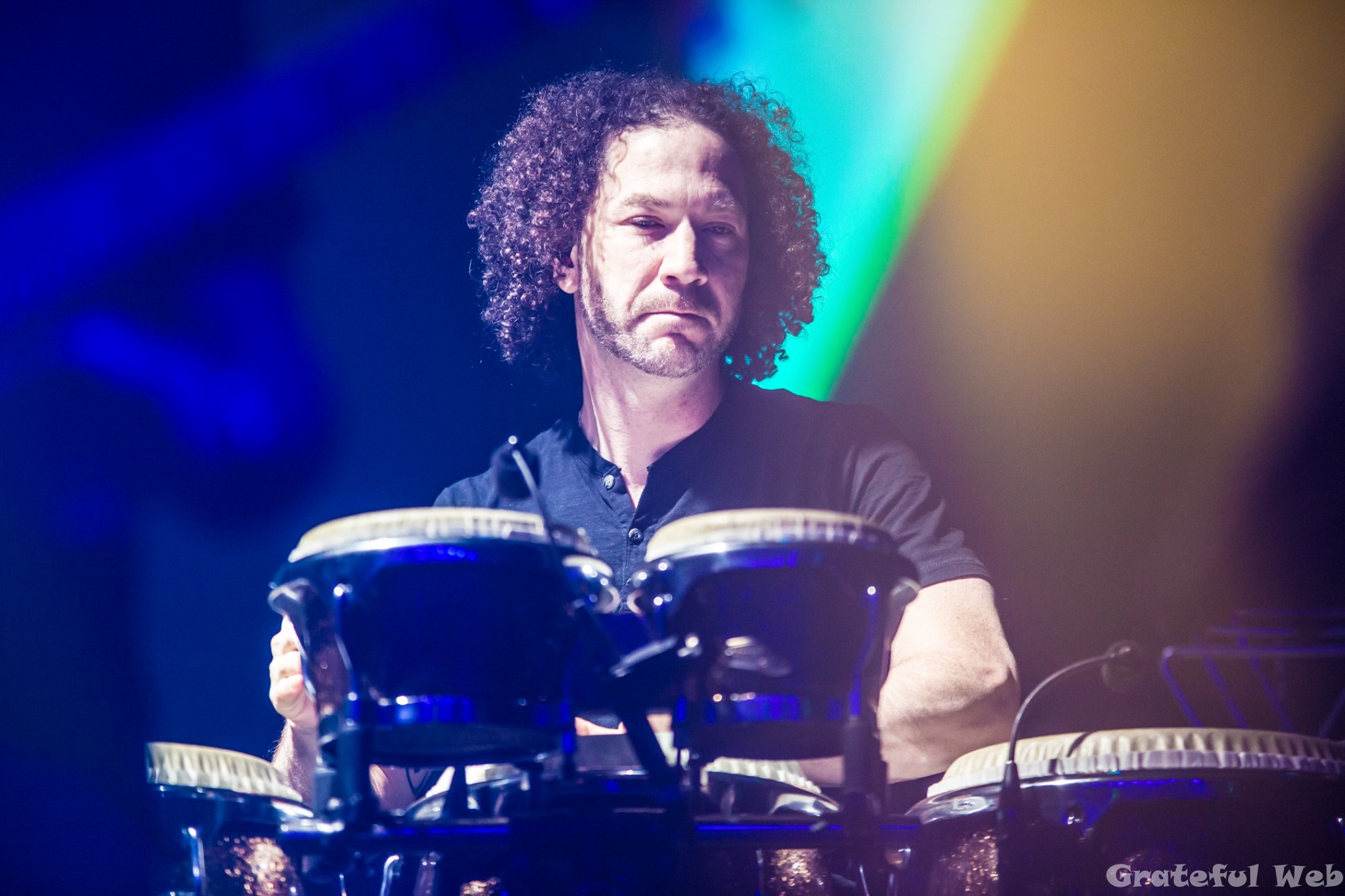

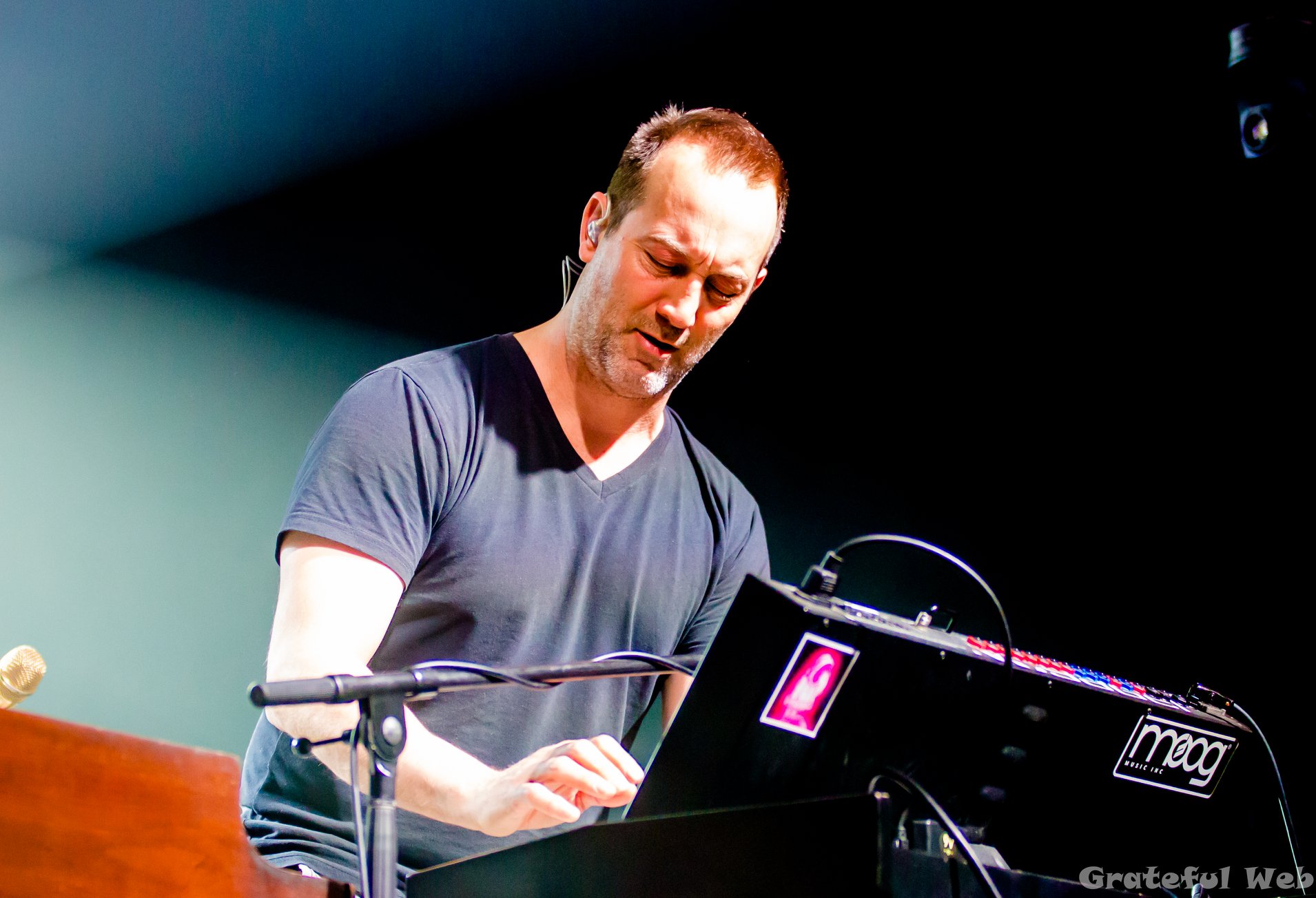

The show’s first song, “It Doesn’t Matter,” quickly established a crispy, Friday night, party vibe. Bass-player, Ryan Stasik fingered a tight, rump-shaking groove and the house bounced to life. Keyboardist, Joel Cummins furnished cosmic atmospherics. Drummer, Kris Myers drove a ferocious beat, and his partner, percussionist, Andy Farag rode shotgun, side-kicking like the Sundance Kid. The immediate impact of Umphrey’s dynamic ensemble play made a powerful impression.

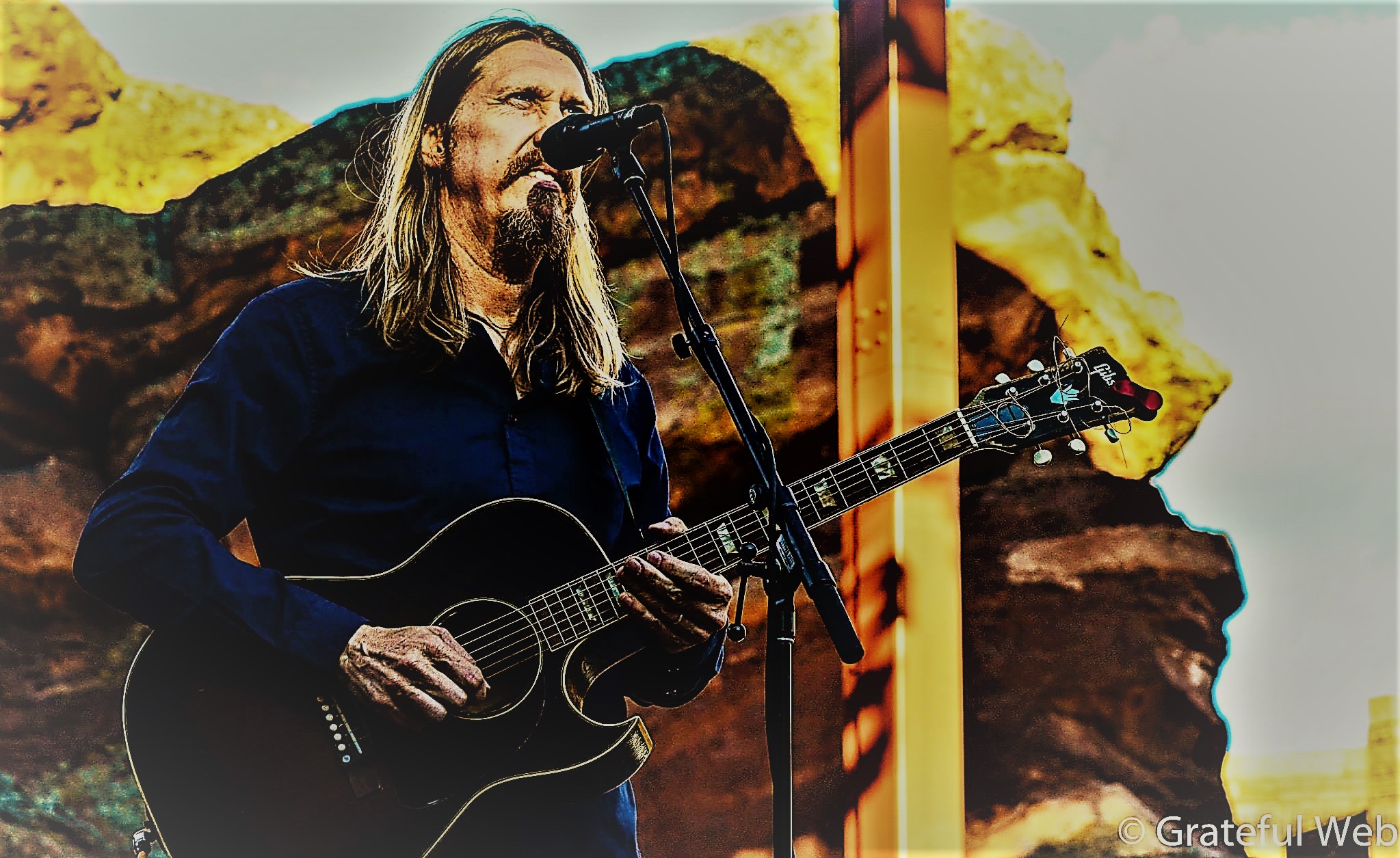

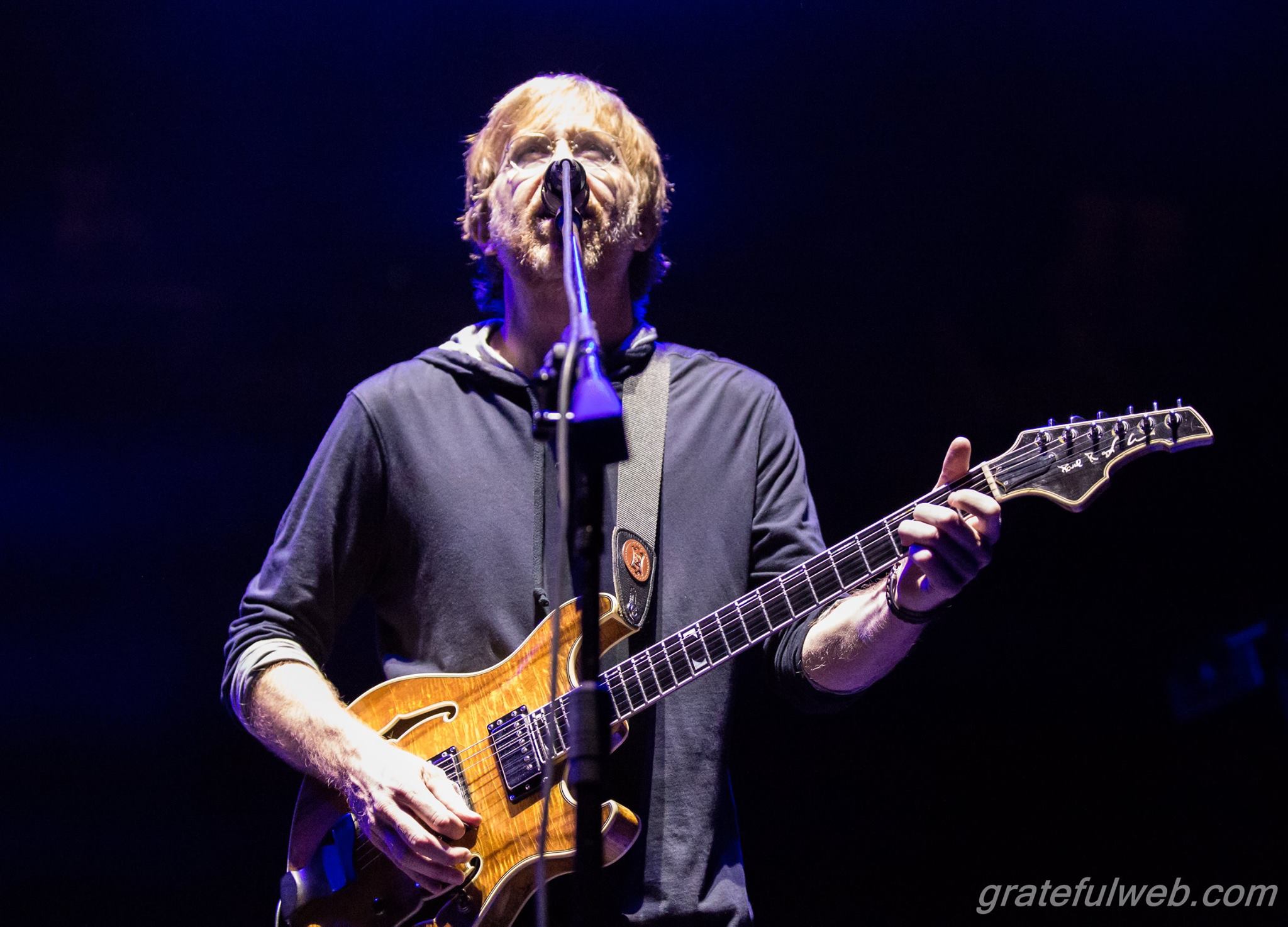

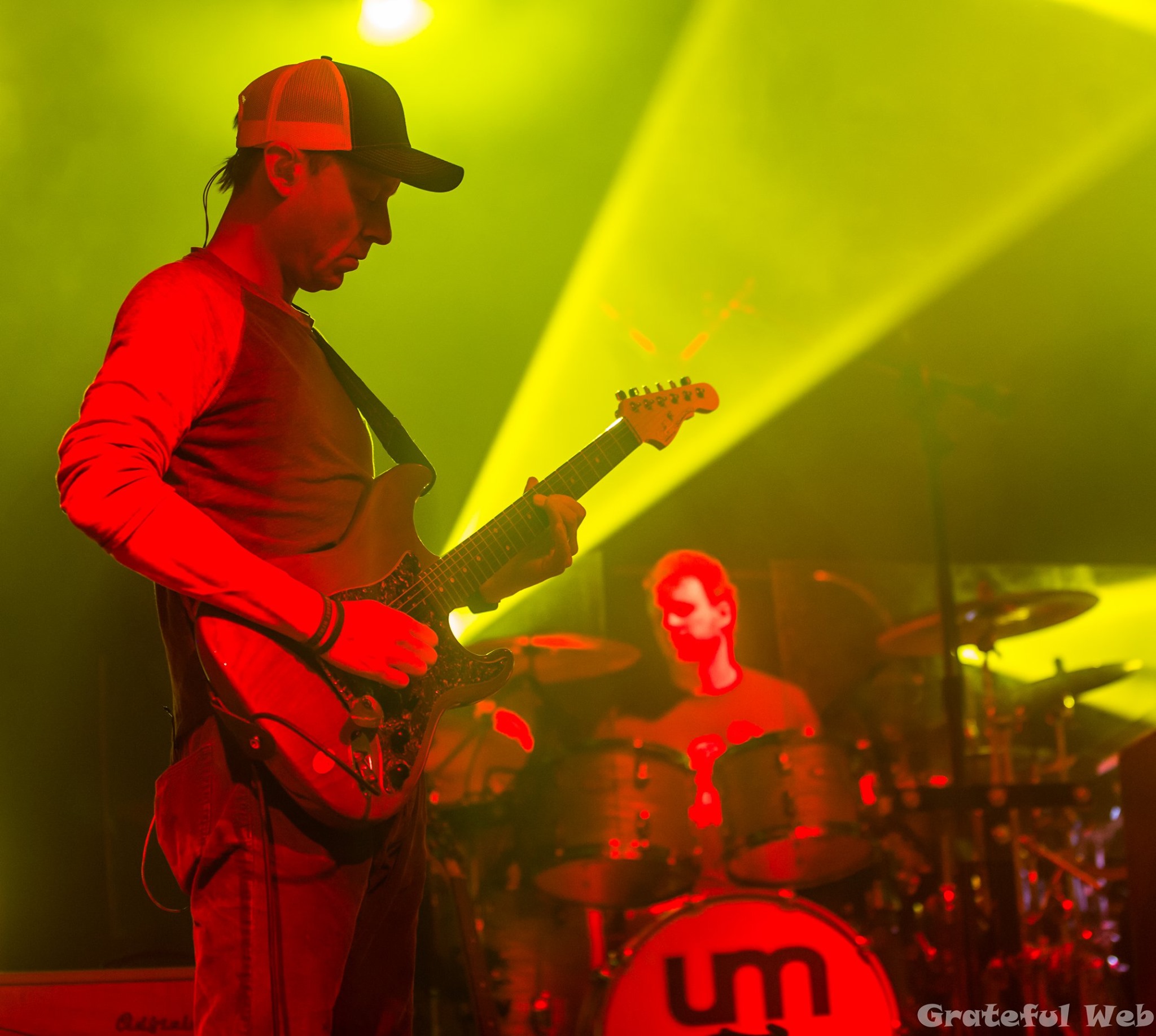

Above all else however, Umphrey’s stop in Eugene forcefully celebrated the electric guitar. Brendan Bayliss and Jake Cinninger have, after nearly 20 years playing together, developed the intuitive, interlocking relationship that characterizes all the best twin-guitar attacks. They answer each other’s questions and finish each other’s sentences, combining in their finest moments to create a compelling compound expression. Both are capable artists, but time and time again at the McDonald, Cinninger burst to the forefront and emptied his bottomless bag of spectacular guitar licks.

On “It Doesn’t Matter,” Cinninger stepped on his wah-wah pedal and plucked the juicy, vaguely Japanese-sounding theme. The group produced a few bars of intense Montreux Jazz Fest fusion, then Cinninger unfolded a sequence of variations that combined equal parts muscular thrust and music theory. He appeared energized and inspired, alternating between chunky, funky, rhythmic scrubs and fret-dancing, high-altitude ascents.

The entire unit crackled and sparked as they shifted into a section of eye-widening improvisation. The song snarled with fist-pumping, head-banging menace. A recurring feature of Umphrey’s sound, their songs often threatened to explode into full-blown metal assaults. Just as the adrenaline-fueled transformation was about to break loose, the group pulled out and returned to the song’s infectious hook. “It Doesn’t Matter” immediately gripped the crowd’s attention and squeezed.

“Divisions” offered a comprehensive, eighteen-minute sample of UM’s complex, sometimes baffling song structures. “Divisions” initially hit like pleasant, if lyrically intense, indie rock. Bayliss’ vocals resembled Ed Crawford’s from fiREHOSE, the 80’s college rock band that grew from the remains of the legendary Minutemen. The song glistened with a soft-focused nostalgia for beer-can cluttered, poster-smeared apartments blasting poignant, adolescent yearning from taste-making hipsters’ record crates.

But, Umphrey’s changed colors quicker than a chameleon in a kaleidoscope. After two minutes, the drummers signaled a shift. A pulsating rhythmic pattern emerged. The band circled, Cinninger took hold, and by the three-minute mark, “Divisions” sounded like “Grand Illusion”-era Styx. Umphrey’s then elevated the arena-rock atmosphere further with a gigantic two-headed, eight-limbed drum segment from Myers and Farag. The chomping metal beast loomed again momentarily before Bayliss returned with more verses, and we were back on campus, slouching stylishly on a secondhand couch.

The song reached a sneering, slacker climax, which could have been the end, but Cinninger and Bayliss instead produced a captivating exhibition of their duel-guitar dexterity. Gliding weightlessly, the pair chased each other over a series of steep, screaming peaks until Cinninger eventually found a bright, blue, breaking dawn tone, and the group slid delicately into the song’s stirring refrain, with Bayliss affirming, “Soul embrace/we’re all the same.”

“Divisions” was a stunning musical statement, but the song seemed to lose itself amid furious experimentation. The tune’s central emotional component became diluted by its disjointed structure. The expansive middle sections of “Divisions,” while instrumentally impressive, sounded unnaturally attached rather than organically conceived.

One of the highlights of the show, and another vivid example of Umphrey’s mad scientist technique was the genre-blending “Number 5>Domino Theory>Number 5” combination. The track surfaced with an icy/hot, acid jazz feel, as Stasik stated the strolling theme. Cinninger twisted a haunting, twangy figure and sent slinky, springy notes wobbling through the air. It was a high-grade, laid back buzz before the unsettling motorcycle gang appeared to forebodingly bark at the moon. At times, Umphrey’s jarring metal injections produced a GWAR-like parody effect. It was hard to know if they were donning the leathers seriously, or with their tongues pressed firmly in their cheeks. “Number 5” was a sensational, though slightly disconcerting amalgamation, alternating dark shades of Deep Purple with the mystical chill of Thievery Corporation.

In a surprising, though agreeable turn, Farag emerged through the revolving door with his congas, and jettisoned the band into another fascinating, improvisational space. Cinninger, of all things, peeled off Chuck Berry’s signature “Johnny B. Goode” lick, a puzzling choice, even for the expansive musical montage of Umphrey’s McGee. Was JC implying there wasn’t a note in the book he hadn’t mastered? Was he casting himself as Berry’s mythical guitar slinger? Or, was he referencing Marty McFly, who in “Back to the Future” suggested his parents’ generation “might not be ready” for his own shredding, Hendrix-inspired version of Berry’s iconic tune? A humorous nod to the latter perhaps, because Umphrey’s maniacal mutations were blowing people’s minds.

A throbbing, grungy rocker, “Domino Theory” detonated over the surging patrons, and for a brief instant threatened to ignite a mosh pit, though glassy-eyed wisdom prevailed. Umphrey’s McGee stomped and spit indignance like Bad Religion or Rage Against the Machine, “If I roll up my sleeves/you should just stand back/stand back.” But, they left the onslaught unfinished, rapidly cartwheeling into an otherworldly, effects-dripping exploration. UM sculpted shapes and contours of a science-fiction novel. The guitarists engaged and initiated the crystal cyan glow of a spacecraft’s thrusters. Slashes of pinched, phased chords reverberated mystically, then gleaming alien figures wriggled and probed. Cinninger ultimately launched a frenzy of piercing notes that caused skulls to ooze molten awe. In the next instant, Umphrey’s boomeranged back into the seething tempest of “Number 5.”

Intense, transcendent prog-rock wrapped in the dark, studded cloak of death metal, this jaw-dropping song sequence characterized Umphrey’s jolting, high-octane concoction. The reprise of “Number 5” featured fantastic keyboard accompaniment from the nimble Cummins, who deftly alternated between zany, swirling synth sounds and ghostly, luminescent passages of piano. The song shattered and reformed, and when it finally stopped, it left smoking craters, vaporized heads billowing fumes of disbelief.

A rare “Ride on Pony” provided a welcome change of pace late in the first set. A swaying power ballad in a glittery, classic rock style similar to Mott the Hoople, “Ride on Pony” was refreshing for its uncomplicated structure as much as its breath-catching tempo.

UM ended the mammoth first set with another ten-plus-minute think piece. “Mulche’s Odyssey” melded Umphrey’s metal circus with the frenetic, oddball energy of Phish. The group again stretched in a shape-shifting jam. Cinninger and Bayliss conjured a furious squall. UM’s hard-hitting, Iron/Crimson creature shook loose and shrieked. The pulsating, white-hot climax swiftly swerved into the dreamy, warm body flow of a celestial, ganja-infused dub. Umphrey’s remarkable ensemble play was frequently amplified by relatively shred-less sections of simply “feel good” grooves. Cinninger (and Bayliss) still played amazingly in these spots, but the reduced amplitude and bite opened spaces the entire combo could skillfully explore. The band flipped back to their churning, metallic power-stance, and fired off a searing, cranial strike.

Giggling, somewhat woozy fans stumbled into the lobby, bar, and street at set-break, mumbling things like “next level” while contemplating the overwhelming prospect of what might possibly follow. UM’s second helping provided its fair share of fireworks, but a discernable pattern emerged. Umphrey’s continued to expertly, at times brilliantly, recapitulate their primary conceit throughout the remainder of the show. They put fans in a spin cycle and alternated wildly through a connoisseur’s collection of classic guitar sounds, from ballsy to erudite.

“Der Bluten Kat” introduced a kicking rock riff with an exultant, call-and-response vocal. Like earlier offerings, “Der Bluten Kat” intermittently flashed audacious, steel-tipped claws. The absorbing jam replicated a variation of UM’s fantastic, intergalactic, machine-head soundscape. This extraterrestrial, musical alloy shaped many of Umphrey’s most exceptional and imaginative moments.

An astonishing cover of Prince’s “I Wanna Be Your Lover” highlighted the band’s instrumental prowess and flexibility. Bayliss managed an impressive impersonation of the Purple One’s falsetto, and Cummins’ sexy keyboard thrusts recreated the swinging, 80’s bounce of the Revolution.

“Syncopated Strangers>North Route>Syncopated Strangers” repeated the now familiar carrousel ride of alternating musical styles. Hints of Herbie Hancock, Rainbow, Hawkwind and Return to Forever whirled keenly. A cyclone of engaging sounds, from funky to Phishy, sinister to sublime, flooded the theater and liquified Umphrey’s ecstatic fans. “Hajimemashite” moved majestically, avoiding sudden jerks or spasms, and presented an uplifting, empowering embrace. The fifteen-minute, set-closing version of “The Silent Type” shifted from swaggering, spirited rock to a sailing, interstellar joyride and back again for a final shimmering transfiguration.

Umphrey’s core idea of a heavy, 21st-century progressive-rock band is an intriguing proposition. Their variety of stylistic influences, when properly integrated, molded a fierce, futuristic synthesis of beast and brain. UM rarely sustained these imaginative structures even for the length of a single song, however, preferring to veer between divergent impulses rather than bringing the inspired hybrid to complete maturity. The unsteady architecture of Umphrey’s songs confounded as much as excited or inspired.

“Shifting gears,” as it were, is standard procedure for the jam-band genre. Moving fancifully from point A to point B is a trademark exercise, but Umphrey’s transitions exhibited symptoms of ADD at times, instantly discarding one idea for another rather than gradually unwinding a harmonious progression.

UM’s most enthralling moments undoubtedly occurred during their lengthy improvisational jams. Clearly defined, successful pieces of stylistic fusion dazzled. Suggestions of second-gen Joe Satriani crossed with alien Zappa juice slid from Cinninger’s fingertips. No matter how distinctive or diverse the path however, every improvisation reached a similar arena-sized, ceiling shattering crescendo. It’s hard to fault a band for rocking too hard, but Umphrey’s repeated ALL CAPS exclamations initiated a law of diminishing returns.

In Eugene, Umphrey’s functioned predominantly as a platform for Cinninger’s high-flying exploits. He produced scalding flourishes and was the most animated performer in the band. He favored flashy demonstrations of technique over expressive touches of emotion, though he appeared capable of everything. The flow of his ideas occasionally progressed like a strobing sequence of musical snapshots. I preferred Cinninger’s space-jazz, prog-fusion blend to his persistent interjections of leopard-print Van/Malmsteen. I marveled at Cinninger’s obvious mastery of his instrument, but his approach evoked a collection of scintillating sounds more than a focused, distinctively characteristic voice. The same might be said for the group as a whole.

There is an intellectual, post-modern quality to UM’s method of cutting together sound bites from sources both strange and familiar. There’s something avant-garde in their abstract formalism. Umphrey’s exceptional musicianship asserts a divinity of design over emotional expressionism, but their ideal shape is elusive. UM are most potent when they are the masters of their influences, rather than the other way around. Umphrey’s bold, combustible mixture kicks harder than their hyperactive collage.

An unusual entity on a jam-band circuit that largely champions psychedelic, folk and blues-infused rock, Umphrey’s McGee are supported by a strong contingent of loyal fans. The Eugene faithful emerged from this rare Oregon appearance suitably entertained. UM’s unrelenting, hard-rocking intensity went “to eleven,” and stayed there the entire show. Umphrey’s high-energy, experimental soundscapes scorched psyches and left lingering, thought-provoking impressions.