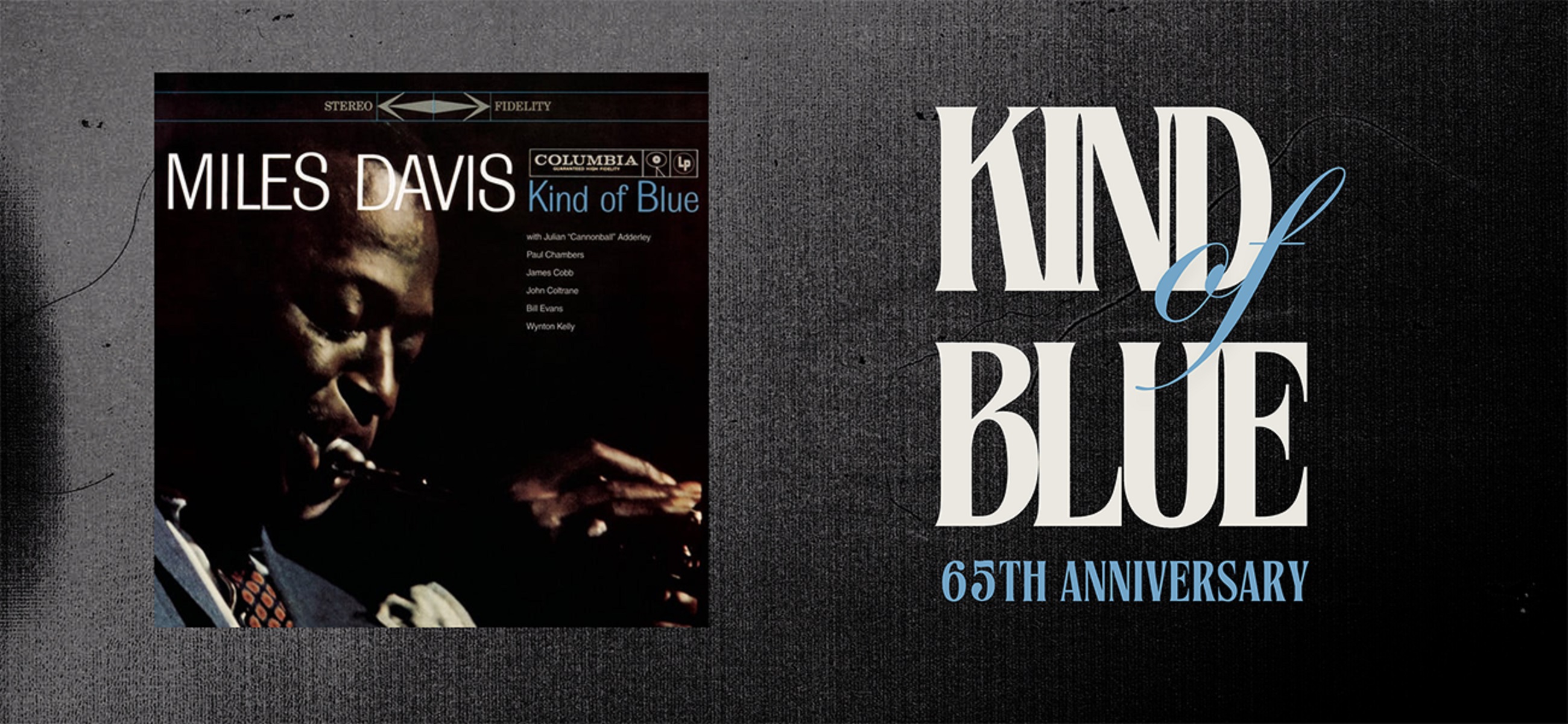

Celebrating the 65th anniversary of Kind of Blue, it’s impossible not to marvel at the timeless brilliance of this album. Released on August 17, 1959, this record not only altered the landscape of jazz but also became a beacon of innovation for generations of musicians across genres. The genius of Kind of Blue lies in its radical simplicity — a deep dive into modal jazz that allowed its players to explore a more spacious, minimalist approach, focusing on melodic freedom over complex chord progressions. Let’s explore each of the five compositions that comprise this masterpiece, 65 years later.

1. "So What"

The album opens with "So What," perhaps its most recognizable track. The iconic bassline by Paul Chambers, alternating between two notes, immediately sets the stage for what is to come. It embodies the modal approach of the album, where the Dorian mode allows for a more horizontal improvisation across a single scale rather than the vertical harmonic structures typical of bebop. Miles' trumpet plays with a lyrical elegance, almost as if asking a question, while Coltrane and Adderley respond with fluidity and distinct voices. The call-and-response nature of the track offers a zen-like quality, where space and silence become as crucial as the notes themselves. Bill Evans' piano comping is delicate and spacious, hinting at modal harmonies that color the simplicity with depth.

2. "Freddie Freeloader"

The second track, "Freddie Freeloader," features Wynton Kelly on piano instead of Bill Evans, contributing a bluesier and more soulful feel. The tune is a traditional 12-bar blues, but like everything on this album, it transcends the formula. Kelly's piano is playful yet grounded, setting a contrast to the moodier compositions surrounding this piece. Miles’ muted trumpet exhibits a cool, restrained swagger, while John Coltrane’s solo bursts with energy, exploring every nook of the blues form. Cannonball Adderley adds a more exuberant tone, and Chambers’ walking bass keeps the track bouncing. In essence, this track reminds us that even within the simplicity of the blues, the room for expression is limitless.

3. "Blue in Green"

"Blue in Green" is the album's most introspective piece, a haunting ballad that feels suspended in time. Often attributed to Bill Evans due to its impressionistic harmony and delicate touch, the piece is a perfect example of Miles Davis' mastery of mood and atmosphere. The structure is unconventional, with a circular form that almost mimics the ebb and flow of an unresolved conversation. Miles' trumpet sounds mournful, each note hanging in the air with a sense of longing. Coltrane's brief solo adds an extra layer of melancholy, while Evans' piano chords shimmer beneath the surface like a calm, reflective pool of water. The piece is both minimalistic and richly textured, embodying the essence of jazz as an emotional language.

4. "All Blues"

The longest track on the album, "All Blues" is a classic 6/8 shuffle built around a simple vamp that repeats hypnotically, allowing the soloists to stretch out and explore its harmonic landscape. The piece features the same modal underpinnings as "So What," but the waltz-like rhythm gives it a lilting, almost folk-like feel. Miles' use of a Harmon mute gives his trumpet a plaintive, almost vocal quality, while Coltrane and Adderley bring contrasting energies to their solos — Coltrane with his intense, searching lines, and Adderley with his soulful, blues-drenched phrasing. The mood here is laid-back yet charged with an undercurrent of tension, a hallmark of Davis’ ability to create subtle emotional dynamics.

5. "Flamenco Sketches"

The album closes with "Flamenco Sketches," a deeply meditative piece that serves as a journey through five different scales or modes. The result is an exploration of mood and color rather than a structured composition, giving each soloist complete freedom to move at their own pace through the scales. Miles’ trumpet is full of restrained emotion, as if he's cautiously exploring uncharted territory. Coltrane, with his searching, spiritual tone, adds a layer of transcendence, while Evans' piano provides a harmonic bed that feels almost like a series of watercolor washes, blending seamlessly into one another. The track feels like a reflection on the entire album — peaceful, contemplative, and timeless. It brings Kind of Blue to a gentle close, leaving the listener in a state of calm reverie.

Kind of Blue has been revered not only for its compositions but also for the improvisational genius of its musicians. It was groundbreaking for its emphasis on modes rather than chord progressions, shifting the focus from technical complexity to melodic exploration. The result was an album that felt more accessible yet infinitely deep. Miles Davis’ leadership allowed the individual voices of his bandmates to shine while creating a cohesive whole that resonated deeply with jazz aficionados and casual listeners alike.

As we look back 65 years later, Kind of Blue stands as a testament to the enduring power of simplicity in music. Its influence extends far beyond jazz, touching genres like rock, classical, and ambient music. The album’s modal approach opened up new avenues for improvisation and composition, and its emotional clarity continues to resonate with each new generation of listeners.

In celebrating the anniversary of this monumental work, we are reminded that true innovation doesn’t always come from complexity, but from the freedom to explore within limitations, creating music that feels as fresh and modern today as it did in 1959. Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue remains a blueprint for artistic expression, its colors still vibrant and its moods still relevant.