If one were to arbitrarily cite any popular music act from the sixties or seventies there is a fair chance that the performer or performers in question, at some point in their respective careers, had a working relationship with or at the very least was in some way associated with multi-faceted entertainment duo Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan, otherwise known as Flo & Eddie. Indeed, during their heyday Volman and Kaylan recorded and performed with the likes of Joni Mitchell, Bruce Springsteen, Alice Cooper, Frank Zappa, John Lennon, Harry Nilsson, and Marc Bolan just to name a few. So why might it be that the mention of these two highly successful performers in general discussion is more likely to illicit blank stares than any kind of informed engagement? There are layers to the answer, just as there are to the group's circuitous voyage through the belly of the beast that is rock and roll. Volman and Kaylan made their respective names on the scene in the late sixties and early seventies primarily through the musical execution of others' ideas. In 1971 the two established themselves as the creatively self-sustaining duo Flo & Eddie, but in order to gain a true understanding of the performers' journey one must look further back.

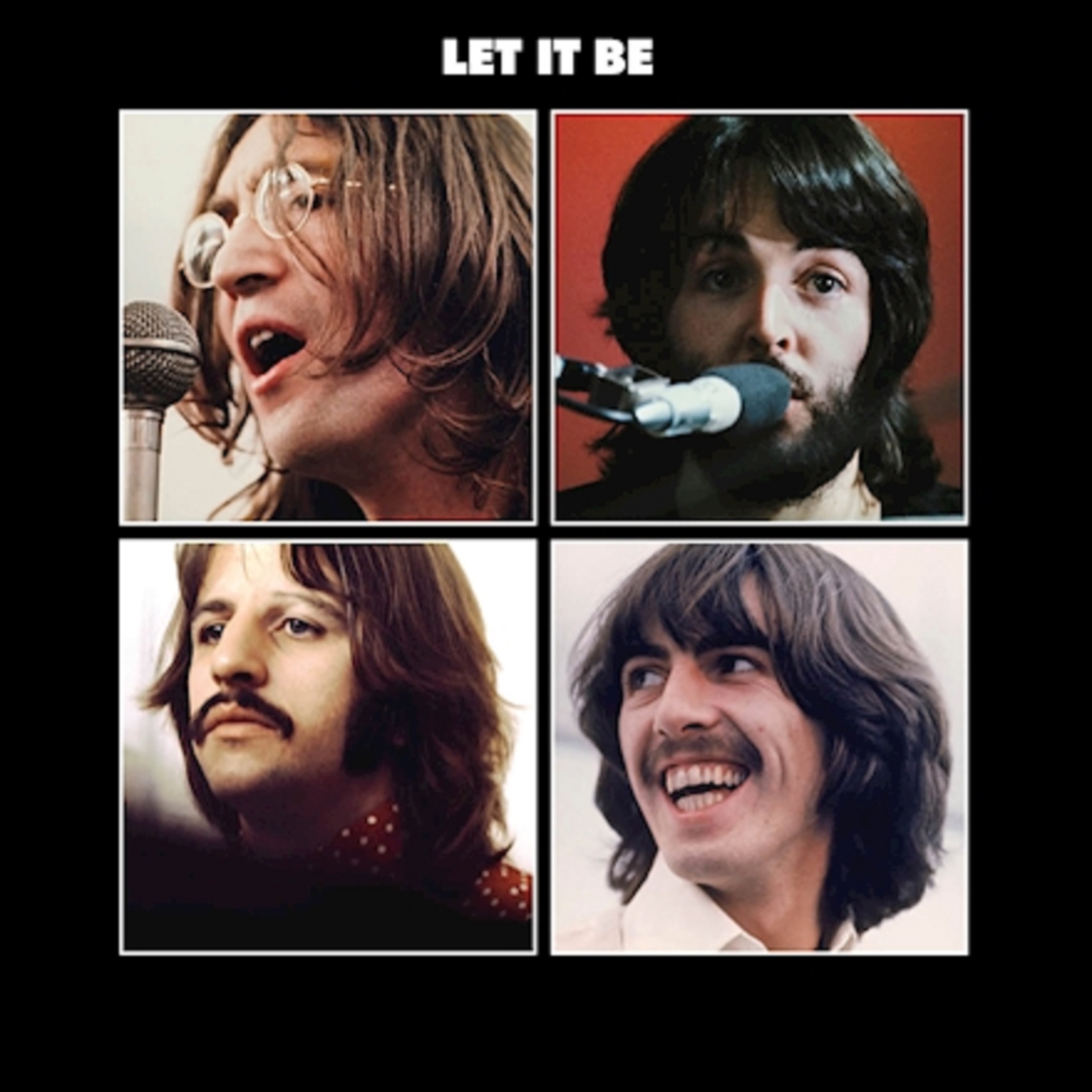

The year is 1967, and the singers who a decade later would be infamous for their stage antics and proclivity for inappropriate humor have just scored a number one song with their group. That song was “Happy Together” and that group was The Turtles: a slap-happy amalgam of Los Angeles youths who had become a band only two years prior. The enormous success of the single attracted much attention, and soon the group was being mentioned in the same breath as many of its contemporaries including The Beatles who served as the inspiration for the band's name. The tunes were satisfactory, some even exceptional, and the harmonies were ethereal. However, if the idea was to replicate what The Beatles were doing (and this most certainly was the idea with any pop band functioning in the late 1960s,) then The Turtles image, it seemed, left something to be desired. Out front on lead vocals, Kaylan, a less-than-conventional looking pop star by his own account, was often flanked by the even less conventional-looking Volman who, with his idiosyncratic on-stage antics and eccentric demeanor, attracted much attention from audiences and served to further diversify The Turtles from their contemporaries. The success of “Happy Together” brought the band members into close proximity with many of the most successful stars of the time, and they cheerfully rubbed shoulders with contemporaries such as Donovan, Brain Jones, Ray Davies, and Jimi Hendrix among others. Not everyone on the scene was so keen to extend a warm welcome to the new kids on the block, however. Kaylan's captivating 2013 autobiography Shell Shocked: My Life with the Turtles, Flo and Eddie, and Frank Zappa, Etc. details a less-than-congenial meeting of the minds at London's Speakeasy Club where then-Hollies member Graham Nash introduced The Turtles to The Beatles, although George Harrison was notably absent. Pleasantries were exchanged and things appeared to be going smoothly, that is until Turtles rhythm guitarist Jim Tucker found himself on the receiving end of an unprovoked verbal lashing from an inebriated Lennon. Tucker was apparently so upset by the exchange that he immediately left the club, booked a plane home, and never played music again.

Up to this point The Turtles had essentially been a vehicle through which record executives could exploit the viability of the musical trends of the day, distributing pop songs to an already over-saturated market and reaping the subsequent rewards. Like many young artists experiencing pronounced success for the first time, The Turtles began to wonder whether they were being adequately appreciated and compensated for their abilities. In short, they were not, and they knew it. By this time Volman and Kaylan along with the other members of the group had already been monetarily picked apart by a host of dishonest managers who, recognizing the naivete of their young clients, were happy to provide a litany of contracts which would ensure that the money earned through The Turtles music made its way to their own pockets. By 1970 the band had initiated litigation aimed at rectifying discrepancies found within the books of their record label White Whale. Frustrated with the creative restrictions imposed upon them and disenchanted with the music business as a whole, The Turtles ceased to exist.

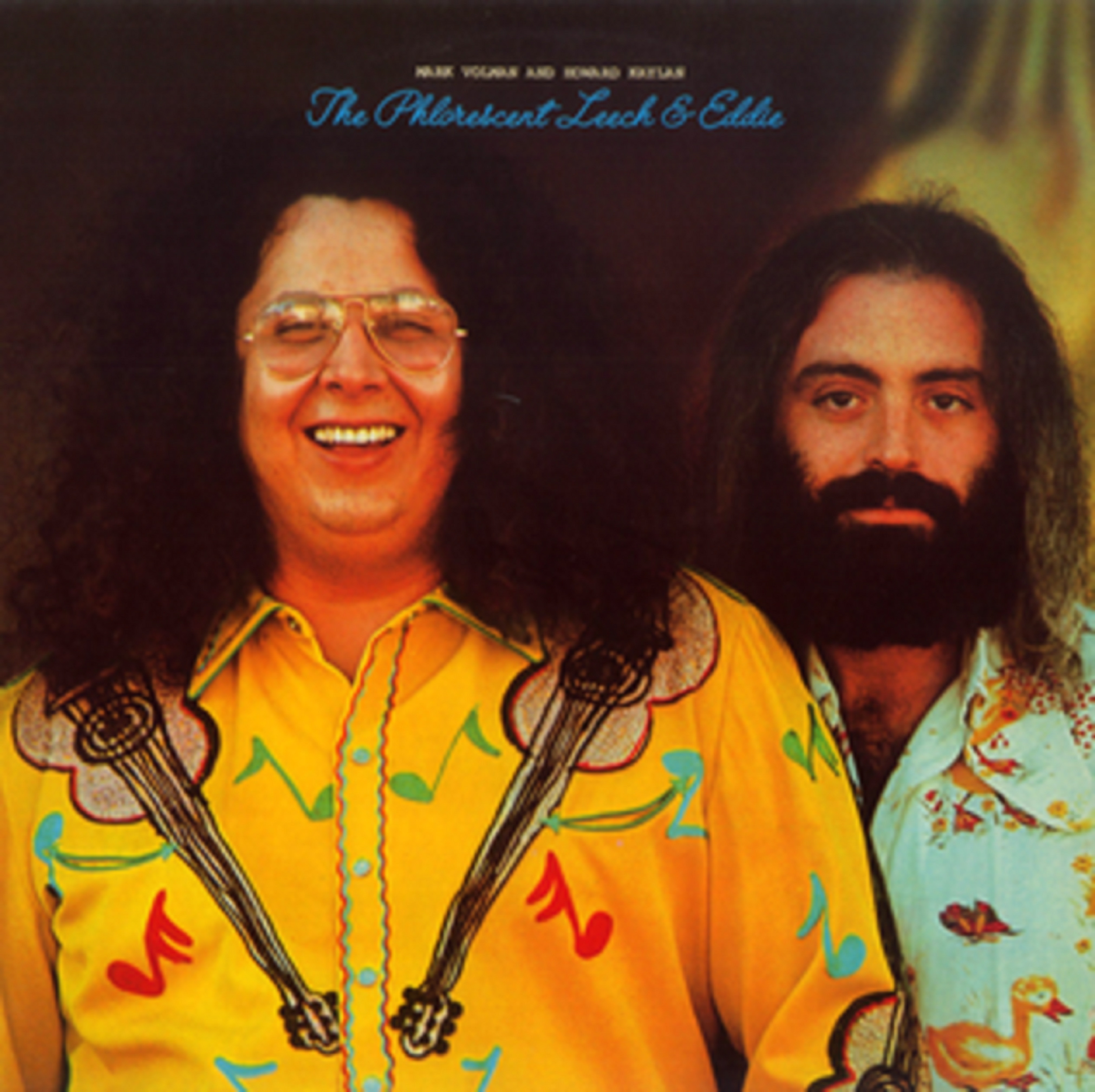

Out of work and out of contact with their fellow members of the now-defunct Turtles, Volman and Kaylan had found themselves in a somewhat aimless drift professionally. As fate would have it, the two had previously made plans to attend a performance by The Mothers of Invention and the Los Angeles Philharmonic at UCLA's Pauley Pavilion. Backstage post-show, the two had an exchange with bandleader Frank Zappa who expressed interest in the potential integration of the pair into the upcoming lineup of his Mothers of Invention for which the personnel would be completely overhauled save for the inclusion of saxophonist/keyboardist Ian Underwood and later a returning Don Preston, also on keyboards. The pair would soon become an onstage fixture in the presentation of the maestro's eclectic, often contentious material, their Vaudevillian shtick serving as the foundation of the exhibition much to the horror of Turtles fans throughout the country. With the listening public's perception of the two as family-friendly peddlers of disposable pop songs effectively shot, a rebranding was in order. Compounding this quandary was the series of execrable deals made by the two throughout the 1960s, at least one of which legally prevented them from using their own names professionally. In keeping with the absurdist image their new employer had cultivated with his band over the years, Howard Kaylan and Mark Volman made the decision to become the Phlorescent Leech & Eddie. Kaylan would take on the role of the intentionally misspelled Phlorescent Leech or Flo for short, while Volman would be Eddie, although a subsequent album jacket misprint would permanently reverse the monikers.

Consistent with Zappa's character, the band stayed busy during this period, playing a number of live dates as well as appearing on four albums in just over two years. This era of the Mothers of Invention culminated in a now-infamous December concert at London's Rainbow Theatre where the bandleader was assaulted by a disturbed concertgoer at the end of the show. Zappa had been shoved from the stage, and as the band peered down at his broken form at the bottom of the orchestra pit, they were all but certain he was dead. Zappa would survive the incident and would eventually recover, aside from a handful of physical idiosyncrasies he would carry with him for the remainder of his life. However, the recovery process would need to go on for over a year, which meant that once again Flo & Eddie were out of work.

The following stage of the duo's career would be indicative of the sharpest contrast between real-time cultural significance and prevalence in the collective memory of the listening public. This is the crossroads at which the primary query posed within this exercise comes the closest to approaching any kind of satisfactory answer. Having achieved massive pop success early on and sharpening their technical skills during their tenure interpreting the genre-defying works of Zappa, it appeared all the singers needed was a proper push to make their own impact on the industry. Mark and Howard decided at this point that they would strike out as a duo backed by fellow out-of-work Mothers of Invention alumni Aynsley Dunbar, Don Preston, and Jim Pons. The pair secured a deal with Reprise Records and recorded their first standalone album, all that remained was to decide upon a name for the group. “We certainly weren’t Turtles anymore, and Volman and Kaylan, or the other way around, sounded like either lawyers or butchers” Kaylan mused in his autobiography. At the suggestion of their new record label, the group decided to appeal to the Zappa fan base with whom they had just spend years developing a significant amount of goodwill. It was settled: the record would be self-titled and the artists the artists at the helm would be professionally known as The Phlorescent Leech & Eddie or Flo & Eddie for short. Kaylan’s autobiographical reflections continued:

“The entire name was a dumb thing to do. Anyone in their right mind, anyone who really intended on having a career in the music business would eschew such a moniker in a heartbeat. But the dye had been cast, and fate had decreed that for the rest of our career as a duo the two of us would never be able to shake that moronic handle. Without it we could’ve been a contender.”

The 1970s were, for all intents and purposes, meant to be the decade when Flo & Eddie stepped out of the shadow cast by the banners under which they had built their careers performing, and propelled themselves to stardom. The idea was a sound one, but as with most things that have seen consideration in theory but not necessarily in practice, this too would prove to be a more complex operation beneath the surface. While the idea was to appeal to as many markets previously engaged by Volman and Kaylan as possible, the rollout gave the appearance of a group whose label knew not what to do with them. Most of the music comprising the debut album The Phlorescent Leech & Eddie dated back to the later years of The Turtles, featuring more of a Laurel Canyon type of singer/songwriter sound than the avant garde, genre-bending, technical mastery that had defined the Mothers of Invention. Their signature humor permeated the proceedings, but there was no shortage of drama throughout the record’s 40 minute runtime, with standouts including Volman’s groove-infused “It Never Happened” and Kaylan’s true-to-life confessional rocker “Feel Older Now.” In short, the image being presented did not appear to line up with the music being presented. The group had put too many eggs in too many different baskets, leaving no dependable market on which to lean. Still the group were able to sustain for a time as a successful live act joining fellow Zappa-protege Alice Cooper on the road for the School's Out Tour, a tour which would propel him to mainstream stardom.

The Phlorescent Leech & Eddie was released in 1972 to positive critical reception but tepid sales, although the two were having moderate success as a live act with their backing group, playing with such acts as The Beach Boys, The Doors, The Kinks, and of course Alice Cooper. Aside from fronting their own band, Flo & Eddie began to make a name for themselves as studio backing vocalists and would contribute to recordings by T.Rex, John Lennon, Stephen Stills, and many others. Perhaps the most widely consumed instance of the duo's contributions to the work of another artist would come at the tail-end of the decade in the form of Bruce Springsteen's "Hungry Heart" which was released in 1980. While the two were keeping sufficiently busy, Reprise still had little idea how to effectively present them as an act. Alice Cooper producer Bob Ezrin was brought in to helm a second album from the group, the results of which was 1974's "Flo & Eddie" which, in keeping with the trends of the day, featured a more rock-oriented approach than did its predecessor. Commercially, the results were more of the same, and the pair soon parted ways with Reprise Records.

Artistic misfortunes notwithstanding, the mid-seventies would be the period during which Flo & Eddie would embrace the mediums through which they would be sustained during the coming years, those being film and radio. During their brief stint with Frank Zappa, Volman and Kaylan became acquainted with Charles Swenson, director of animation for Zappa's 200 Motels film project in which the two were featured along with the rest of the 1971 Mothers of Invention lineup. Swenson had developed an animated film called Down and Dirty Duck and had the two in mind for its primary roles. The project was pitched in 1973 and released in 1974 with Volman and Kaylan contributing voiceover acting for the main characters as well as providing the aggregate of the film's music. Although the film was poorly received, it did serve to continue the development of the relationship between the duo and the animation studio behind 200 Motels and Down and Dirty Duck: Murakami-Wolf-Swenson. As the pair's multi-media profile began to grow, a wider breadth of opportunities would present themselves, including a slot hosting their very own radio show on Los Angeles station KROQ during which they would play records and converse with popular contemporary artists. The show proved to be successful, and the two implemented a more comedy-centric approach for their 1975 album Illegal, Immoral and Fattening, though their increasing profile did not translate to formidable records sales. 1976's Moving Targets brought the focus back to music, but it was becoming increasingly clear that the interest of the general public lied more with the personalities of the performers than with their newly recorded output. It bears mentioning that the content within the song-centric Flo & Eddie albums could be considered on-par with the output of many of their contemporaries by an objective listener. Speculation can be made as to the root of the act's commercial folly within the musical realm, but the glaring fumbling of their initial rollout by Reprise Records in 1972 remains perhaps the most highly probable conjecture.

The final years of the decade saw Flo & Eddie assume house band duties for Canadian late-night talk show 90 Minutes Live, for which they also conducted interviews with numerous artists including David Bowie, Tom Waits, and Lou Reed. Seemingly cognizant of their own commercial strengths, the early 80s would see the pair's career as a contemporary music act wind down with their final releases of new material: 1981's Rock Steady with Flo & Eddie, a collection of reggae numbers, and 1982's Checkpoint Charlie, an electronic, new-wave EP released under the alias which served as the project's namesake. It is perhaps no coincidence that the decision to close the book on this era of their career came shortly after they were again contacted by the Murakami-Wolf-Swenson animation studios, this time in hopes that they would contribute music to a television special based on a character which featured in greeting cards. The character was Strawberry Shortcake, and the specials proved to be a hit, spawning an expansive and consistently popular franchise that remains successful today. Flo & Eddie composed the theme music and contributed songs for the first three specials which lead to their involvement in many subsequent films and television projects including The Care Bears.

In 1983 Volman and Kaylan acquired the legal rights to The Turtles' name and quickly set about putting together a retrospective touring act which would serve as the basis of their performance-based income indefinitely. Over subsequent decades the pair would continue to work in radio and television, as well as pursue personal interests. Howard Kaylan had two short stories published in best-selling anthologies, along with his aforementioned autobiography. He also penned the 2003 film My Dinner with Jimi which was based on the night The Turtles met The Beatles. In 2006 Kaylan released the solo album Dust Bunnies. Mark Volman went on to pursue higher education, earning his bachelor's degree from Loyola Marymount University as class valedictorian in 1997, as well as his master's degree in 1999. Volman has since taught at Loyola, Los Angeles Valley College, and Belmont University. The Turtles continue to tour successfully in the present day, and the pair that have always seemed to be everywhere and nowhere all at once appear to have happily settled into their own legacy. Having endured as turbulent a ride as any act of their time, the pair who made the decision to boldly step out on their own half a century ago remain happy together.