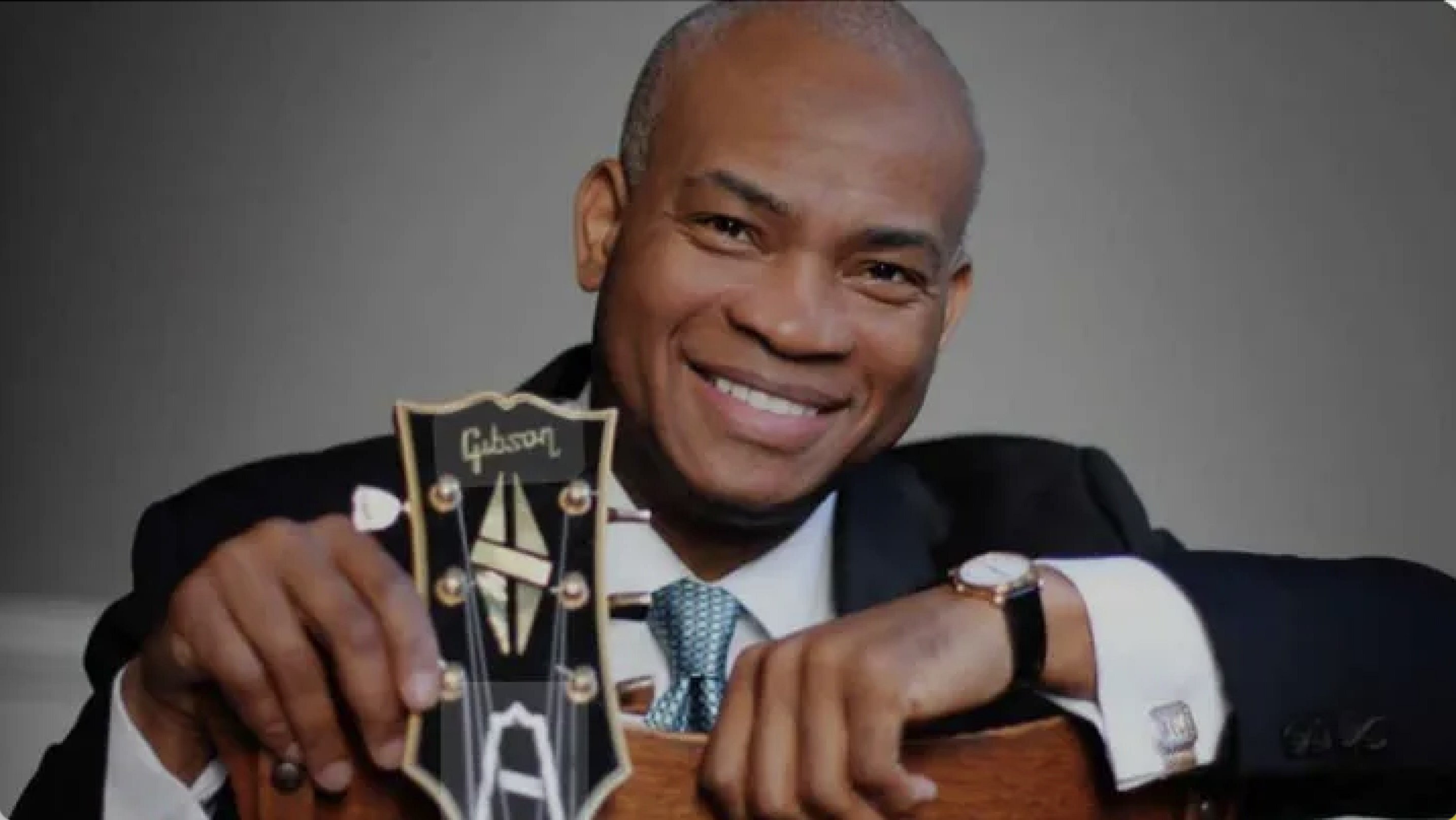

There’s nobody quite like Roger Kellaway. In a career that has stretched over the last 60 years, while performing with many of the legendary jazz musicians of his time he has also written memorable film and television scores, composed classical works for major symphony orchestras, inspired what came to be known as “new age” music, and provided essential accompaniment and musical direction for iconic figures of American popular music like Elvis Presley, Barbra Streisand, Bobby Darin, Tony Bennett, Van Morrison and Joni Mitchell. Although Kellaway’s soundtrack for the Streisand film “A Star is Born” received an Oscar nomination, and his compositions have been performed at Carnegie Hall and elsewhere by the likes of the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, and National Symphony orchestras, he still may be most widely recognized for the closing theme (“Remembering You”) of the 1970s mega-hit TV series, All in The Family.

Kellaway chose to celebrate his 80th birthday in November at New York’s Birdland, historically known as the “Jazz Corner of the World,” to engage his abiding passion for straight-ahead, uncompromising and above-all-else swinging jazz, performing with a "drummerless" trio in the tradition of Art Tatum, Nat Cole, and Oscar Peterson. The celebration marks the return of one of the very few remaining figures from the “golden age” of modern jazz to the iconic jazz club where he first performed almost 60 years ago. IPO Recordings is recognizing the event with a new album aptly titled “The Many Open Minds of Roger Kellaway.”

Kellaway’s rich and varied career in music reflects his philosophy that: "the idea that anything can go with anything is very appealing to me, and music has taught me that the options are infinite." As he says, “many different kinds of music interest me, and how to make them all. You know: how do they all work? I was always curious about that. I was always curious, and I still am, about every single player that I play with. You know, it always occurs to me that there’s a music lesson in every player that you play with. You just have to listen and sort of figure out how to accompany them and make the most music together.” He looked back on those lessons in a recent interview:

You had a long and close association with Bobby Darin…

I learned my stage timing from Bobby Darin and Jack E. Leonard [the comedian who provided Kellaway’s first paying gig].

What are the secrets of stage timing?

[laughs] Nobody's ever asked me that question before! I don't know what they are. It's a relationship… Okay, here's one: when you finish a tune, and the audience is applauding, you must start the next tune before the applause is finished. If you wait until the applause is finished, the show is dead.

You don't want to hit that dead spot, you want to keep everything alive. You want to ride that energy. You know, Bobby brought a particular kind of energy to the stage and you want that to stay there throughout the whole show.

Did he look to you to communicate [that energy] to everyone on the bandstand?

Yes, yes, but it wasn't talked about. It was just… just do it.

I was intrigued that you had written the score for the Streisand film “Star is Born.” What was that experience like?

Well, do you remember EST? I had just finished EST, I was having a conversation with Barbra and Jon Peters, her husband at the time, about that. And Barbra said to me, “Well, you know, we're shrink people.” That was her answer.

But the thing about EST was, I didn't have to take anything personally, and of course, you know, Barbra’s reputation precedes her in terms of perfection and changing your mind and all kinds of stuff.

There was one particular piece of music [of mine] that she liked, and I included some of that music in the first piece that I wrote for the orchestra. And I went into the booth. She was playing it back. And she turned to me and said “Why did you write that?”

I wrote it because I thought it fit the film. And I thought she'd be knocked out because it had to do somewhat with that piece of music that I knew she liked. Anyway, I went home and stayed up rewriting half of that first piece of music, until about three in the morning and then it had to go to the copyist because at nine I had to conduct that. And she accepted that one.

Later on, I was talking with pianist/conductor Marvin Hamlisch. He wrote a lot of charts for her. He said, “You know, you have to get used to writing three charts on every single song. The first chart she'll hate. The second chart, she might like a little bit. And then the third chart she’ll probably like.”

We look at this as “That’s her process.” But she’s brilliant.

You’ve worked with another famously perfectionist artist: Sarah Vaughan.

Well, Sassy was very friendly to me. I just, I enjoyed that. I did a movie with her; she was very pleasant and very musical. This movie was a CBS movie of the week, and we recorded that with just a small group: me on piano, Chuck Domanico on bass, and Shelly Manne on drums.

And Sassy was in many moments, you know, what are called playoffs or “play ons.” At the end of the TV segment, the button that you make is called the playoffs and then as the next team comes on you usually play Intro music and that's, you know, playing the scene on. She was asked to look at the chord changes and improvise, and that was fun. So her part included improvising and doing the main song which was called “The Days Have No Names,” and the lyric was written by Gene Lees. It was very enjoyable.

I was intrigued by the connection to Elvis -- when did that come about?

Well, Elvis was ‘68 or ‘69. And I was merely hired as a piano player to play a double session at Universal I didn't know it was for Elvis. I walked in and there he was. We were doing the soundtrack for his last movie, “Change of Habit.”

And we spent the whole day together. It was just wonderful. There is a CD. It's on RCA; it's called “Let's Be Friends.” At that session, he was joking around about the fact that, you know, we all had long hair and ankhs and stuff. He was talking about his early years, and all the gyrations and everything on stage. That is not the personality that I met. The guy I met was a real gentleman: good sense of humor, just a really nice guy. I always liked his ballad sound.

The fact that I spent one day with him has followed me all my life. And I really enjoyed that. You know, that I got to touch him, and I got to play with – accompany him -- and it was really nice.

Tony Bennett?

I love Tony Bennett. I did 10 concerts with him in 2005.

We're at our second gig. The first gig was in Toronto, and then we took a G3 [Gulfstream 12-seater] to Cincinnati or wherever it was. [Next morning] The road manager calls me and says “Mr. Bennett would like to see you at one o’clock” – at the piano, on the stage. So I meet him at one o’clock, and he says, “Don’t overplay me.” I said, “Okay.” Then he turns around and walks away. That's all it was about, but a very, very important lesson for me on how to accompany him.

What led you to Paul McCartney's music, in particular?

I was not a fan, when the Beatles first came along, because, obviously, the music industry was changing… it [pop music] just simply left jazz behind.

So, I didn't pay any attention to Paul for a long, long time. And then I started working with this entrepreneur Dennis Domico. He had had some contact with Linda [McCartney] and her Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and he wanted to do all-McCartney concerts – beginning to end, all Paul’s music.

His feeling about doing a McCartney song was he would only do songs where Paul wrote 85 percent or more. He had hired a pianist for one concert: Peter Beets from Holland. So I started thinking about two pianos, and the first thing that came to mind was “Yesterday” at a very fast 4/4, two pianos, bass and drums -- and that's how the whole “Many Moods of McCartney” piece started.

I spent a good portion of six years .. reviewing his music, and really beginning to realize what a brilliant songwriter he is.

In order to do something like what you did with “Yesterday,” a melody has to be strong enough to have that kind of resilience.

Yeah, that's right. Absolutely. And all of his songs did not work. Many of them did not work for me, but there were quite a few : “When I'm 64” and “Honey Pie,” many songs that are sort of old English musical theater – with almost kind of a two-beat feel, which I could move into a jazz concept.

The kind of songs people [in a theater] would sing along to in Second World War era music halls...

Yes; I think that’s what Paul grew up on. When you look at the forms of his songs, they’re very strong.

You once said you felt that you had been making music in previous lives. What would lead you toward that state of mind?

Well, I had been reading a lot of mysticism, and a lot of different concepts of psychics that were doing interviews with people that they would hypnotize, and they would take them to past lives; you read in the book, what their experience was all about and it's a curiosity, along with all of my other curiosity about everything else… It’s wanting to get a glimpse of what is possibly like on the other side of the veil. And the veil is what closes over when we’re born on earth. So I was very intrigued by that.

So, I was looking at people who played. And some people who didn't have the technique that I had or the overall music perception that I have — and I looked at it as the possibility that I had been doing it for hundreds of years.

“The Many Open Minds of Roger Kellaway” is a live recording of a Kellaway trio performing jazz standards similarly to his Birdland program. IPO Recordings is a tiny, independent label that has focused on musicians, like Kellaway, with roots in the first generation of classic modern jazz, including iconic players like James Moody, Hank Jones, Frank Wess, Benny Golson, Roland Hanna, Richard Davis and others who came up during the golden age of jazz that followed World War II. While great musicians from that period were marginalized by the recording industry in later years, IPO continued to provide a forum for them to play on their own terms, without pretense and contrivances, collaborating with their contemporaries and talented next generation players. The IPO catalog includes, in addition to a number of albums by Kellaway, entries like the first - and only - recordings together by Moody and Hank Jones; Moody and Kenny Barron revisiting their historic quartet collaborations, including the Grammy winning “Moody 4B” album; the final sessions by Frank Wess, with some astonishingly beautiful duet ballads with Barron; stunning solo piano recitals by Sir Roland Hanna; and group sessions with all of those musicians, along with luminaries like Benny Golson, Eddie Daniels, Richard Davis, Bob Brookmeyer, Jimmy Owens and Mickey Roker, performing tributes to composers Thad Jones and Tom McIntosh. Legendary critic and author Nat Hentoff described IPO’s first Thad Jones tribute album, called “One More – Music of Thad Jones,” as “the perfect jazz recording.”

Over the last half century, Kellaway has:

· Performed and recorded with many of the legendary jazz musicians of his time, bridging all variety of instrumentation and styles, a seemingly endless list that runs from Duke Ellington through Sonny Rollins and beyond.

· Inspired what came to be known as “New Age” music through his “Cello Quartet” albums.

· Composed a variety of works under commission for the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, National Symphony, New American Orchestra, New York City Ballet, as well as chamber works performed at Carnegie Hall. He has a special affinity for 12-tone serial composition, which he studied in depth with Arnold Schoenberg’s protégé, George Tremblay.

· Written jazz “improvisations” performed by classical musicians such as YoYo Ma, Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg and pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet, who recorded Kellaway’s serialist version of Caravan in an Ellington tribute album.

· Written 29 film scores, including the academy award nominated score for Streisand’s “A Star is Born" (or, if you prefer, "Jaws of Satan" - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VIRUm4fgbVc&t=143s).