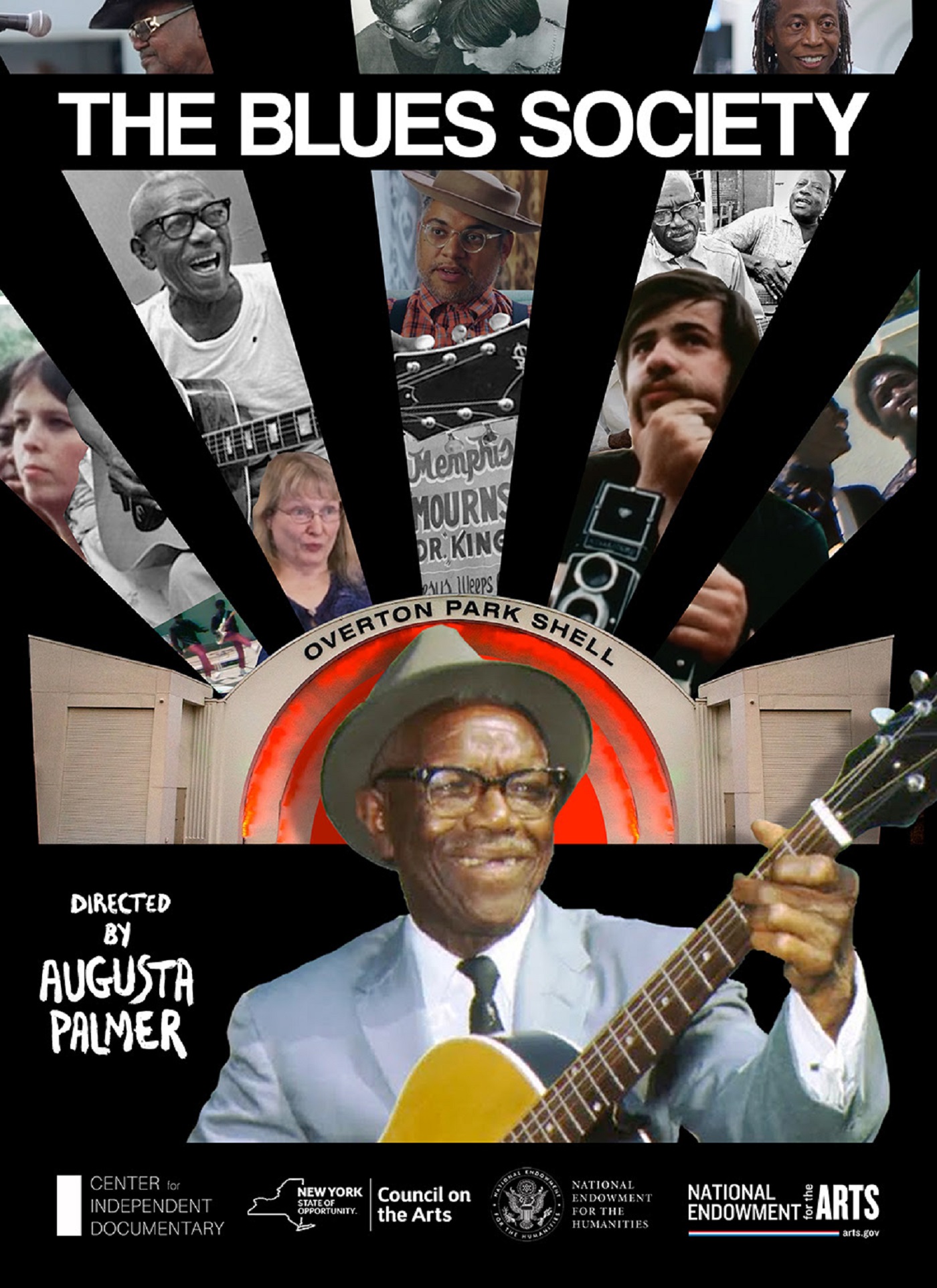

The Blues Society, directed by Dr. Augusta Palmer, is playing select theaters and festivals leading up to its release for rental or purchase on all major cable, satellite, and digital platforms on July 9.

The Memphis Country Blues Festival (1966-1969) all started with a $65 check, a ball of hashish and a bunch of white bohemians who set out to rediscover forgotten bluesmen of the early 20th century. The Blues Society, directed by Dr. Augusta Palmer is a feature-length documentary that reevaluates the life of the Memphis Country Blues Festival through the lens of race, the counterculture of the ‘60s and the genre of Memphis blues.

“I didn’t want to just make a concert film,” says Augusta. “I loved the arc of the story. The initial stake was guitarist Bill Barth’s baseball-size chunk of hash and guitarist Jim Dickinson’s sixty-five-dollar check from a Sun Studios session. It was white and black musicians playing together during the height of the civil rights era. The KKK held a rally in that same public park a few days before. I wanted to understand what this moment meant to the people involved.”

The film follows the festival from its start in 1966 as an impromptu happening, through a period of cross-pollinization with New York’s East Village scene, and up to the 1969 festival, which mushroomed into a three-day event. It garnered substantial print and television coverage, including an appearance on Steve Allen’s national PBS show, Sounds of Summer.

The Blues Society tells the story of blues masters like Furry Lewis, Nathan Beauregard and Rev. Robert Wilkins—who had attained fame in the 1920s and 1930s, but were living in obscurity by the 1960s. It’s also the story of a group of white artists from the North and the South who created a celebration of African American music in a highly segregated city.

Furry Lewis gained a popular following in the ‘20s, but fell into obscurity as the popularity of “race music” fell in the ‘30s and nearly disappeared post World War 2. His touring days were cut short when he lost a leg in a railroad accident in 1917. He worked for decades sweeping the city streets, so the efforts to recognize his musical accomplishments echo the 1968 Sanitation Strike, where each worker’s sign proclaimed “I AM A MAN,” underlining the racist refusal to honor African Americans’ basic humanity.

Folks sought out Furry after he was featured in The Country Blues by Samuel Charters. He played regularly at Memphis coffeehouse The Bitter Lemon, building close relationships with these young blues enthusiasts. He was a father figure to the members of The Blues Society, and they ultimately fought to help him get a pension.

Musician Bill Barth was a cofounder of the Memphis Country Blues Society, played in a band with Augusta’s Father Robert Palmer, and was a central organizer of the festival. He was always looking for the old blues masters, including famously finding blues great Skip James in a Mississippi hospital.

In ‘66, Barth was canvassing for old 78 (rpm) records when he came across blind proto-bluesman of the ‘20s Nathan Beauregard playing guitar and singing. He looked old, and without asking, Barth billed him as over 100 years old. Much later, his draft card and census were found putting him most likely in his 70s. Beauregard would become known for playing his Japanese electric guitar in an almost acoustic style while singing lonesome songs in his high voice. Beauregard passed away in 1970, only a few years after being brought back to the spotlight. He was buried in an unmarked grave. In 2023 Augusta went to the dedication ceremony of a new gravestone for him provided by the Mount Zion Memorial Fund.

“Bill was a blues aficionado, collector and historian,” says Augusta. “He would walk around Memphis going door-to-door looking for old blues records to buy. There’s books and movies about these collectors. I wish that Nathan Beauregard lived longer. There’s not a lot of interviews with him. He was more of a symbol to the Blues Society than an actual person. He was lauded at festivals and by Sire Records in ‘68. But he was not taken care of or properly remembered.”

Reaching into the present, the film ends in a 2017 concert where John Wilkins returns to the stage he last shared with his father Rev. Robert Wilkins 48 years earlier. Robert wrote “Prodigal Son” in the ‘20s, but was made famous by the Rolling Stones in the ‘60s who initially didn’t properly credit Robert. The Blues Society members were outraged. Rolling Stone Magazine wrote an article about it and he was eventually paid royalties on the song. John ended up being the groundskeeper for The Levitt Shell, the new name of the venue of the festivals, and eventually followed in his father’s footsteps in becoming a reverend himself.

Augusta made it a point to bring in diverse voices to give this film a historical context. Memphis writer and filmmaker Jamie Hatley talks about when she was younger that she wanted to separate herself from images of poverty in the blues. And that it took her a while to come around to appreciating the genre. Henry Nelson, a black man from West Memphis, Arkansas, was hoping he could get a ride to Woodstock, but wound up at the Memphis Country Blues Festival. He talks about how his history with the blues is a kind of private thing and how he wasn't sure that it was something that should be shared. Don Flemons discusses how the blues lost its appeal for a lot of young African Americans as we move into the more radical Black Panther era.

“We all love the idea that music conquers all,” says Augusta, “Everyone can appreciate the blues music in this film, but love for this music didn’t cure white supremacy, and white blues fans were part of a power structure that took advantage of black artists. I love the enthusiasm of that white hippy idealism, but the rules were much more stringent back then. There were segregated bathrooms for employees at the bandshell. Racial inequality has become more and more clear to the nation since the pandemic. We’ve come a long way, but still have a long way to go.”

–

The film’s genesis began as a family affair for director Dr. Augusta Palmer. She grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas, went to Rhodes College in Memphis, as well as Sarah Lawrence College, before settling in Brooklyn, NY. Her father, Robert Palmer, was a founding organizer and player in the festival, and her mother was also there tearing tickets.

“I officially started working on this film in 2016,” says Augusta, “but you could say I've been working on it for all my life. When that woman makes a speech at the end, where she's saying, ‘Why can't you just pay for your tickets people?’ to people who snuck in. That's my mom. She was pregnant with me when she made that speech. So, I kind of went to the 1969 Memphis Country Blues Festival. I didn’t know my dad very well until I was a teenager, but this festival was a big part of his life.”

Robert Palmer later went on to become a music critic for the New York Times and Rolling Stone, and authored the seminal blues history book Deep Blues—which in turn inspired the 1991 documentary Deep Blues: A Musical Pilgrimage to the Crossroads.

Getting in touch with her father’s spirit was also the impetus for her debut feature documentary, The Hand of Fatima (2009), which had its U.S. premiere at Indie Memphis as well. It’s about two trips to Morocco. One, her father’s trip in the ‘70s to meet with master musicians and record an album. And two, her own journey to Morocco in 2005 to meet those same master musicians.

“My dad died in 1997,” says Augusta. “He left me a necklace tied to those musicians. I had my own child and I needed to find out what happened there, because he really felt like he was part of that family of musicians. I didn’t meet my dad until 1982 when I was 12, but I heard a lot about Jaouka when he returned there after I started college.”

Both films carry the theme of the power of music across cultures. They ask the questions, what did this moment mean to the musicians, to their audience, to her father, and to Augusta herself?

Music executive and Memphis country Blues Fest organizer Nancy Jeffries was approached by Gene Rosenthal with 16mm footage of Memphis Country Blues Festival that he shot and kept in his basement. Jeffries brought Augusta on board based on seeing The Hand of Fatima. They began developing the film in 2013, but the project stagnated due to rights issues and conflicting ideas on what this film should be. A few years later, Fat Possum Records had bought the footage and put together the 2019 concert film Memphis '69: The 1969 Memphis Country Blues Festival, and they were generous enough to offer Augusta access to the footage.

Augusta continued to work on the film through the pandemic, and had a breakthrough in 2021 when they received their first big grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, then grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the New York State Council for the Arts in 2022. Augusta’s The Blues Society gives context to the performances seen in Memphis '69, and so much more.

“I was putting it together like a collage. There’s stuff in the film I didn’t even find until last year. I had this bootleg tape that someone had labeled ‘1969,’ but when I had the tape transferred we found that it was actually from 1966! So we suddenly had media to work with from that first festival. The primary text from my dad in the film was from an article I hadn’t discovered until late in the process. The film and I both benefited from having that time to think about what I wanted to say.”

Augusta currently has a short fiction film, Order My Step, currently making rounds in the film fest circuit. It’s about an incarcerated woman trying to reestablish a relationship with her estranged daughter.

The Blues Society premiered Indie Memphis and won the Audience Award, won best Doc Feature at the Oxford Film Festival, and will have theatrical runs in New York City, Memphis, Columbus, Ohio and Portland, Oregon before being released to streaming services this summer.

"I've been thinking about more ways to do outreach," says Palmer, "I spent seven years making this cross-generational historic project. We're already working with high school students, and the Music Maker Relief Foundation is working with us to develop ideas. Their mission is to help preserve the music of the American South by helping musicians. We're looking forward to bringing this film to new communities to continue this conversation of music, race and culture."