It’s been said that all the years combine and melt into a dream. This can be true for any entity as it passes into history, and no doubt it applies in particular to the Grateful Dead. The story of this beloved band has been chronicled in numerous books by band members, insiders and close friends, and music journalists. After a while, it all rolls into one.

So yes, the Grateful Dead has its own oft-told, multi-perspective biography that in sum could be taken to define the band. But far too little has been written about the Deadheads. Of course, there are a lot more of “us” (Deadheads) than there are of “them” (members of the Grateful Dead and their immediate circle). Each of us has our own story; how we got into the Dead, our first show, tales from a month or several years spent following them on tour. So many stories to tell, so many roads traveled.

Like the proverbial blind men touching different parts of the elephant, we all got to experience the Grateful Dead in our own unique way. We all melted into our own dream.

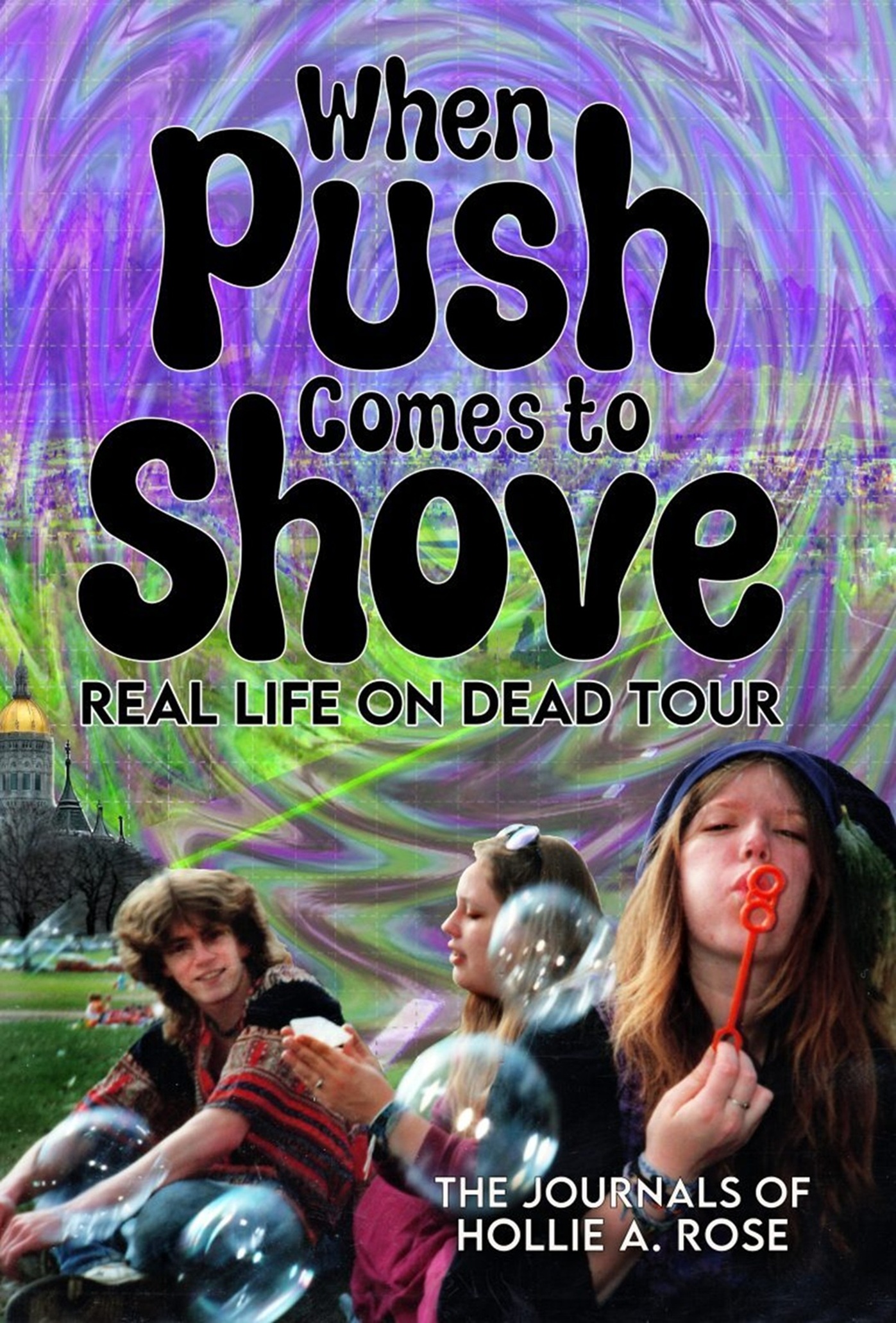

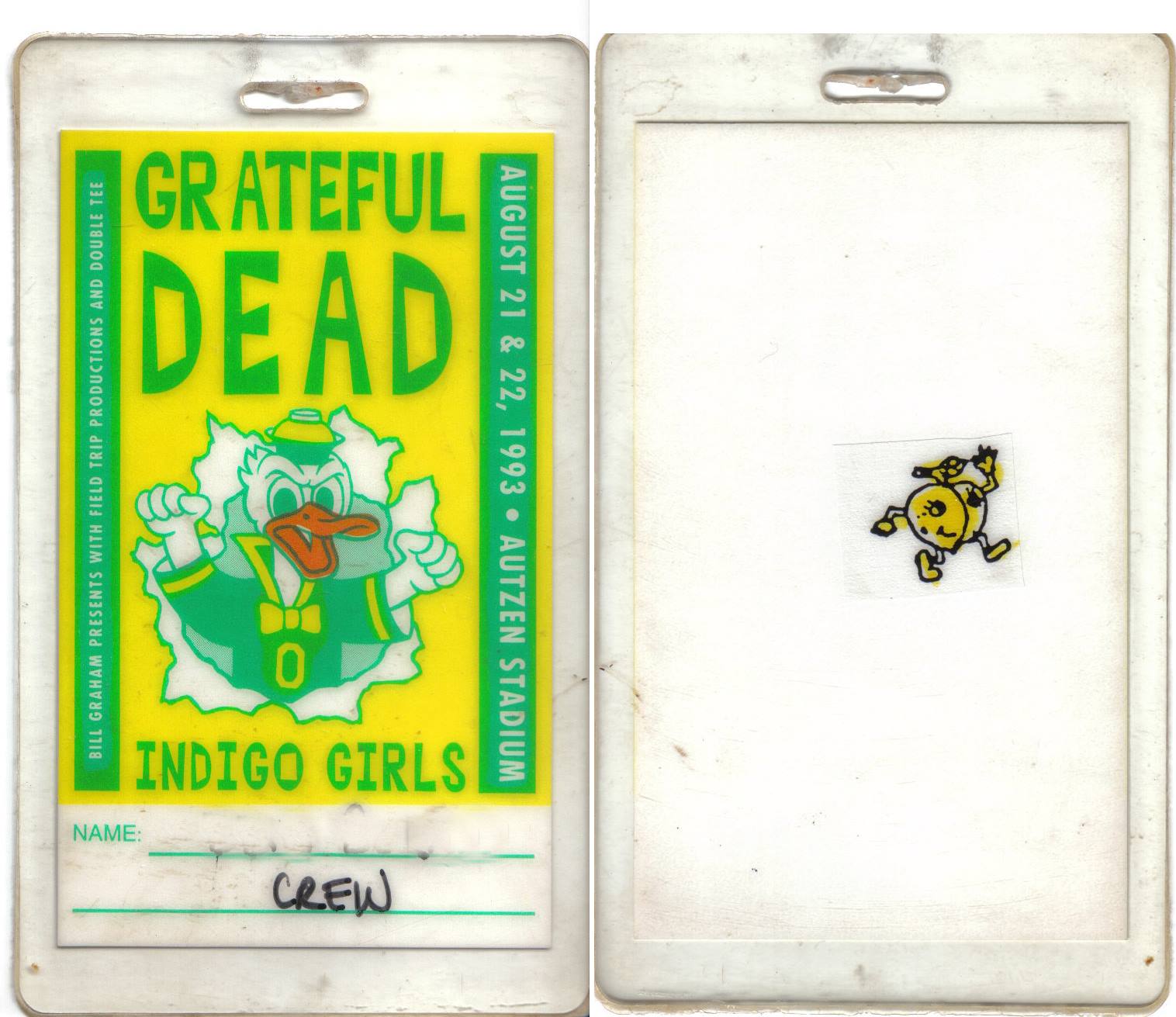

For an intimate, worthwhile, “you-are-there” perspective from a Deadhead who lived “on tour,” check out Hollie A. Rose’s “When Push Comes to Shove; Real Life on Dead Tour” (self-published; available on Amazon). This isn’t a memoir or a history per se. In “When Push Comes to Shove,” Rose, a lifelong diarist, has compiled her journal entries encompassing a period from the summer of 1988 through summer 1992, during which she followed the Dead to nearly every show and lived with fellow Deadheads between tours.

“Picture Grateful Dead Tour. Some folks come and visit, we call them tourists. Others of us find our way to living here full time. We stay. And there forms a hardcore group. Not only are we ‘on tour’ together, we hang together off-tour too. We are family. Some tour for only a season or two. Of course they alter our chemical makeup while they’re here. Everyone who is on tour alters us, changes us as a whole.”

When the Grateful Dead woke up in their hotel rooms, Rose was already hard at work selling postcards (and other things) in the parking lot. When the band hit the stage, Rose was in the hallways, or still outside trying to score a ticket. When Jerry Garcia flew home, Rose and her friends were in the van on the I-70 watching out for cops, or sleeping on the floor of someone else’s hotel room in Philadelphia. When there was no tour, there were plans discussed for the future while living in the “now” of finding a place to crash, some food to eat, some pot to smoke. It wasn’t always easy. But it was often fun, and always real.

Rose’s book reads like a diary because it is one, warts and misspellings and weird punctuation and all. It’s gritty, honest, and introspective. And it’s nothing but the truth, written as she experienced it (often during the very moment “it” was happening). Only the names of her companions and other Deadheads were changed, to protect both the innocent and the guilty. (Disclosure: Rose and I are lifelong friends, and we traveled together on tour during the mid-80s. If she ever publishes a book covering, say, 1985-1987, I’ll probably cringe reading about my younger self. As it is, I’m only in this book a few times, mostly on the periphery. Bonus point for you, Dear Reader, if you discover my alias in the book.)

“As I drove today I gave thanks for some of my favorite things – One is that I love being in the hallway, with the smell of Indica blanketing us, dancing, and seeing all the faces of people I love, as they dance. Sad that each time more faces are missing.”

There’s a well-defined story arc in this slice-of-life adventure. The time frame encompasses some of the federal “War on Drugs,” during which the Grateful Dead parking lot scene was a specific, ongoing target for the Drug Enforcement Agency, as well as state and local police across the U.S. Rose’s circle of friends and acquaintances included a lot of people who were doing various drugs, a large number of them selling drugs – mostly pot and psychedelics – and a tragic few of them succumbing to the worst outcomes associated with those and other drugs, including jail, addiction, and death. The story arc in “When Push Comes to Shove” is wrapped around that environment with elements of hope, allegiance, and camaraderie shadowed by heartbreak and betrayal.

Good times were had, the music was brilliant, the experiences were quite frequently fun and adventurous and funny and serendipitous. But the price for some of the people in Rose’s orbit was dear.

“Bad news between Cincinnati and here. Someone stole the bail $ for Diggety that Kimmy had collected. Also Dragon Dave is still in Jail in North Carolina, and Jean Claude went down in Cincinnati. We are people just trying to live peacefully, be good, and believe, and we get persecuted for drugs. It’s ridiculous. Some people learn a lot from drugs, and use, not abuse, them.”

Granted, this is not the story of nearly every Deadhead, or even every so-called Tourhead. It might trigger memories for people who spent years following the band in broken-down VW buses selling grilled cheese sandwiches in the parking lot. It might just as well answer some questions for people who caught a few shows from time to time – who are those people I always saw in that big fatty circle in the hallway, and how do they all know each other? How do they, you know, live?

There are two ways to read “When Push Comes to Shove.” Start-to-finish is always a viable option. From Rose’s introduction to her indispensable glossary of tour lot lingo at the end, it’s a wild ride. But interspersed between the adventurous stuff there’s a lot of the day-to-day grind; chores (mostly related to eking out a living or just trying to get a bite to eat), long drives, yet another motel room or hearing about someone else getting busted. It’s also a challenge at times to keep track of the “cast of characters,” given that there are scores of people who intersected with Rose across the years covered. Given that, some readers might want to take a different approach – pick a random page, read a few “days,” jump in and out of Rose’s life as you see fit. That’s fine too. You don’t need to “be Hollie” to “see Hollie.”

Sample glossary term: “Cake – often means money or cash, but occasionally it means a baked treat (baked like in the oven, not baked like getting stoned).”

If you were a Deadhead during the late 80s and early 90s, and especially if you were “on tour” during any of that time, “When Push Comes to Shove” likely will resonate with you, jog your memory, bring you back to those mostly good and possibly (though hopefully not) bad times. And perhaps if you weren’t there, “Push” will illuminate an era of Grateful Dead history from a perspective you hadn’t considered. The Grateful Dead were nothing without the Deadheads. Deadheads mattered.

I recently discussed Rose’s book with Rose over email, followed up by a long conversation. Here are some excerpts from our dialogue.

Gabriel David Barkin (GDB) You've been a diarist nearly your whole life, and I know you have journals that, altogether, cover decades. What is it about this period covered in “When Push Comes to Shove” (the late 80s through the early 90s) that made you want to create a book? What is so special or distinctive about that time period?

Hollie Rose (HR) I started my touring with the Dead in 1983. It took me a long time to zero in on a story that was in some way transformative for me, because let’s face it, any time spent with the Grateful Dead was usually transformative. As I whittled down my voluminous stream of consciousness journals – a process of removing all the bits that weren’t all that important – I saw that this time period of the journals is where my writing style changed somewhat. At some point in 1988 I crossed a threshold of “writing my life” as I had always done and moved on to “writing because something here was very important” and writing is how I understand myself.

GDB How long did it take you to make this book happen? What were the most challenging and rewarding aspects of that process?

HR I’ve always been fascinated by diaries and journals and personal life writing – the works themselves as well as the process of creating them. I spend a lot of time studying journals just because they interest me. Honestly, I always thought my own journals were shit compared to those I studied. I always knew I wanted to write a book about my time with the Dead someday, so when I wrote the journals, I thought that all I was doing was taking notes for the day I’d write that book.

In the summer of 2016, I was working on the transcription of my journals (a lifelong project for a lifetime of words) when I stumbled upon the awareness that these notebooks of mine showcased all that is wonderful about journal writing – the immediacy, the unpredictable nature of life, and the raw truth of a moment.

Then I thought – “Ha! This is the book right here! I’ve already written it!”

I thought – “This is going to be easy!”

Eight years later I finally was able to publish a book I could be proud of.

The most challenging part was to continue work on a massive project like this while life keeps on happening around you. The rewarding part – finding my own truth in the avalanche of words my stoned pen scribbled.

GDB Tell me about "journal" vs. "diary" vs. "memoir" vs. "history": How do you view your book? Where does it fit in?

HR The word “journal” comes from the same root word as the word “journey.” “Diary” comes from the same root word as “day.” So it’s kind of just a journey through the days. I find those two words mostly interchangeable.

I don’t call this a “memoir” because a memoir is a story told about a transformative time of one’s life, usually with poetic license used to recreate scenes and events, this book is not quite that.

Now, “history” – that’s an interesting question here. Some early readers [of “When Push Comes to Shove”] told me it was the 80s version of “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test,” a history of the scene, and that I was doing a great disservice to use fake names. They said that Tom Wolfe used real names, and I should too. When I suggested it was a history to a knowledgeable book person, I was told, “It’s not a history, however, unless you’ve done historical research, you use other backing primary sources, and you contextualize the work.” (Basically, an attitude that I ought not to think of my work as anything as lofty or as important as history.)

[But] I’ve read enough diaries – from Anne Frank and Samuel Pepys, through the hundreds of diaries left behind by the westward expansion wagon trains, or people involved in wars both on the battleground and the home front – to know that any diary is a history. Go ahead and tell me Anne Frank’s adolescent diary isn’t history. I dare you.

GDB A lot of the book is fun and exciting, but a lot of it is also dark. There are many references to self-abuse and addiction. There are challenges of poverty related to lack of food and shelter. There is a code of ethics in play throughout the book that may affront some people's sensibilities given its disregard for the law (particularly regarding illegal drug sales) and "rules." (How many people CAN you cram into a hotel room?! How many people can get into a show via a door pop?) There is a significant element of betrayal of decisions made in one's own interest at the expense of those considered "family."

Can readers be forgiven if their takeaway from the book is that Dead Tour, at least during the era covered, was a pit of depravity and poverty, a cesspool of drugs and lawlessness? What about readers who conclude that the Feds and police targeting Deadheads were doing society a favor?

HR Well, there is that, isn’t there?

I have joked (but I do not do so lightly) there are some people who may read this and decide that “I” am what ruined the Dead scene. I showed up without a ticket. I took advantage of an open door when I saw one. I sold things clandestinely – hiding my postcards under my sweater to avoid the confiscation police. I smoked pot.

I did a lot of the things I was told not to do. So be it. It was Bob Dylan who said, “To live outside the law you must be honest.”

None of what any of us did was morally objectionable.

As far as selling drugs was concerned: no one in this book was ever what society would call a “pusher.” They used to use that term, remember? As if someone was going to try to force upon you the party favors they were selling. That’s just another way society has warped the truth of a thing. It never happened like that. In fact, I argue that it was absolutely not pushed on anyone. Drugs and the taking of drugs was never a requirement.

he 80s were no different than the 60s in that way. Expanding one’s consciousness is admirable for the sake of all humanity. (Yeah, now I sound like a fucking hippie, but whatever.) People should have that choice, and I’m glad the US is teetering on the brink of all this stuff being legal.

As far as self-abuse – people make their own decisions, and I never saw anyone walking through the lot flogging themselves with a horsehair whip.

And yes, there is indeed darkness here. There would have to be darkness near any light as powerful as the Grateful Dead. Like I wrote on the back of my book cover: “The closer you get to the light, the larger your shadow becomes.”

GDB Conversely, it's my experience that most of the people I hung out with most regularly on tour went on to do things like get college degrees, start businesses, turn their craftwork into profitable income streams, etc. Was there something inherent in the experience of touring – spending time in parking lots, on the road, in shows, etc. – that enabled people to "find themselves" in a way that was beneficial rather than self-destructive? What were the emotional/spiritual/economic growth opportunities for young people who left their parents and hometown behind to go on tour?

HR On Facebook occasionally I see a meme that says something like, “Lifehack – leave your hometown in your 20s.” And I always think – “Hell yeah, go anywhere!”

I don’t think it was so much about “finding ourselves” after tour. I think we’d found ourselves on tour. But it was about having learned and embodied a sense of freedom, an awareness of the limitless nature of existence, the wide expanses of the world, and at least some small hint of our own power. Especially when we first left tour. We were invincible. Some people kind of forgot that as the years wore on.

And while you’re right – the majority of the people I knew on tour went on to become quite successful – some people never got the hang of that freedom bit. Some people spiraled into oblivion never to return. Tour populations were a lot like the real world; there are winners and losers, and lazy folks and driven ones. We thought we were special but we’re just like everyone else.

GDB Thinking about the last two questions, the "bad" stuff and the "good" stuff: was there something inherent in the Tourhead / Grateful Dead music experience that was likely to lead people down either paths of downward or upward spiral? Can you discern any reason why some people ended up in jail for years, or committing acts of betrayal, or winding up dead, while others expanded their opportunities to lead productive, happy lives? In other words, was there something unique about tour, or was it just another microcosm no more or less likely to lead to success or despair than any other social/economic milieu?

HR Your questions here echo what I was talking about above. Look at any high school, and even most colleges, and ask, “Why did some go to jail, some wind up dead, some capitalize on opportunities?” Because that’s how humans move through the world – doing good shit, doing questionable shit, doing dumb shit, getting lucky or feeling targeted by the whole world and adopting a victim stance.

I will say this: tour taught us mad survival skills, and maybe there is a higher tendency towards success because Tourheads were never afraid to game the system.

Some trees will stop growing if you wrap a chain around them and some will swallow that chain like it was never there. Who can say why?

FOR MORE INFORMATION Rose has a website where you can learn more about her book and order copies. Please visit https://flamingohippie.com/

In addition to learning about “When Push Comes to Shove,” visitors can explore and contribute in many ways. Rose has pages dedicated to the following:

• Books by other Deadhead authors

• The War on Drugs: Visitors are invited to contribute – “Did the War on Drugs impact your life? Your story matters!

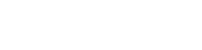

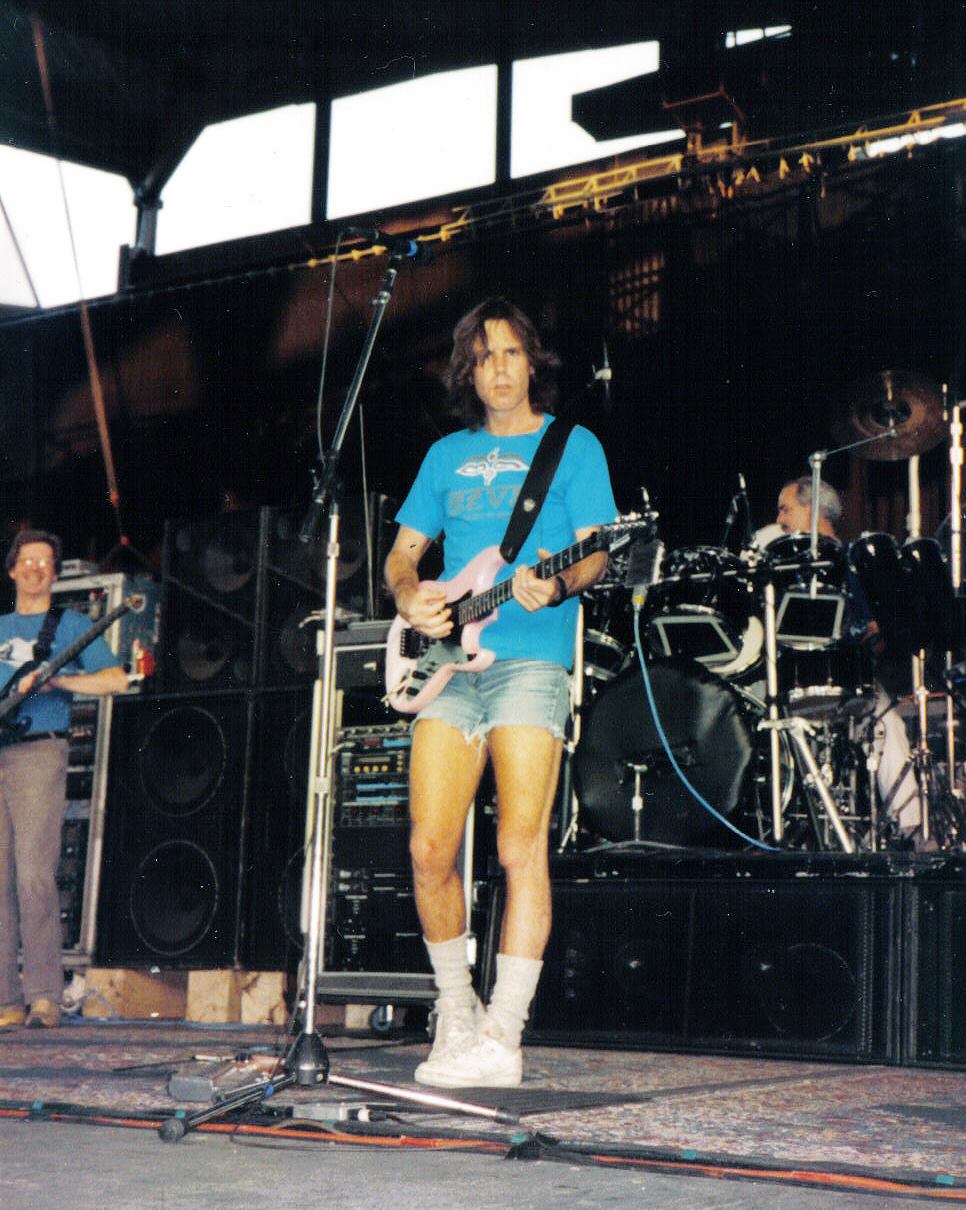

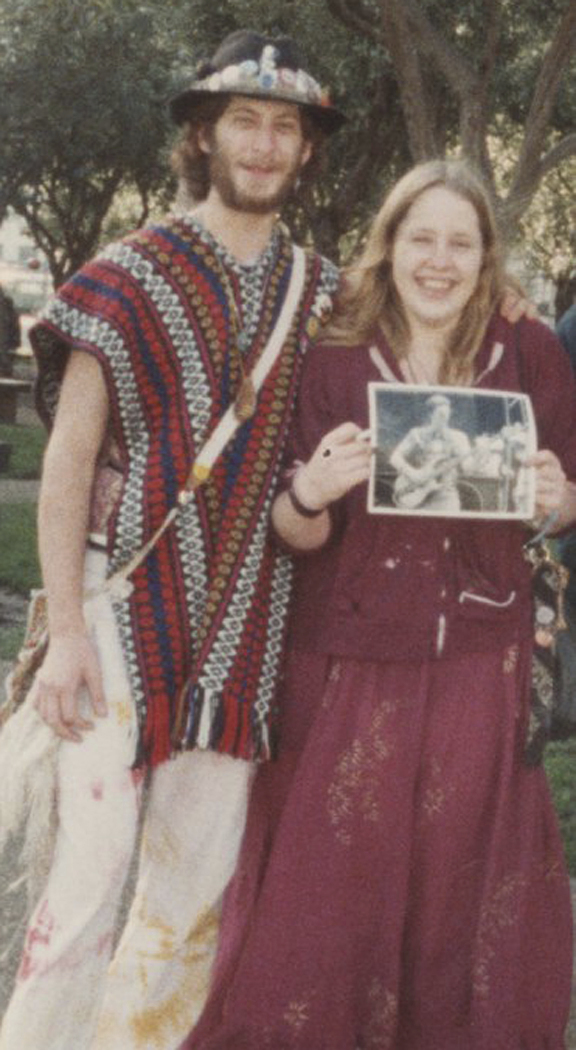

• A photo gallery inviting all Deadheads to upload “images of your tour crew.”