GW: This is Dylan Muhlberg of Grateful Web. I am joined by legendary music photographer Bob Minkin. Bob’s eye for capturing the perfect moment reveals his subjects with unparalleled intimacy. As a teenager of the mid-1970s, Bob began following the Grateful Dead extensively after a nearly two yearlong hiatus from touring. His tact and respect got him closer to the band than any photographer before him. He became the chief photographer for Relix Magazine in in the developmental years of the publication and has since developed an expansive career with numerous publications as continuing clients. The newest milestone of Bob’s career and the collective Deadhead world is the release of Grateful Dead photo retrospective Live Dead. Today we have the pleasure of Bob’s company to get the lowdown. Thanks for joining me today Bob.

BM: My pleasure, thank you for having me.

GW: Live Dead has been in the making since you snapped your first amateur shots of the band on the Grateful Dead Summer comeback tour of 1976. What initially inspired you to bring a camera to shows?

BM: Initially it was to have a souvenir for myself of the experience. Because I liked collecting things. I was a stamp collector before I got into music. It was to remind me of the great time that I had.

GW: The early/mid 1970s saw the Grateful Dead in a sustained level of popularity with younger rock ‘n’ roll fans in the U.S. What other bands were you into as a teenager before you became a bonafide Dead Head?

BM: Well really it all kind of happened at once, when I got into what I called “good music.” It was Jimmy Hendrix, Clapton and Cream, The Allman Brothers, Jethro Tull, The Grateful Dead. The Dead rose to the top.

GW: The Dead around this time were cautious when it came to outside documentation of their concerts including tapers and photographers. What do you think changed in the course of that decade that led them to be more generously open to documentation?

BM: Taping is a whole other world, that I can’t comment a lot on. In terms of photography, when you’re a familiar face and around a lot plus at the time I was shooting for Relix Magazine, which gave me some official accreditation. Before that at some shows I would just sneak my camera in and watch myself. Get in early; sleep out at night so you can get a good seat. But as time went on I met people in and who worked for the band. I got trusted. And that’s really what its all about is trust. That’s what allowed me to get closer to them.

GW: You can see that in those late 70s shows backstage, whether East Coast or West Coast you’re on the inside.

You’ve compiled your career of iconic Grateful Dead photography in the brand new retrospective photo journal Live Dead.

The stunning large hardcover book is a semi-chronological portfolio filled with hundreds of photographs, annotations, and vintage jottings. Additionally it’s filled with praises and prospective from the surviving members of the Dead and their close extended family. Did this project bring to realization everything your photography meant to the band and the fans?

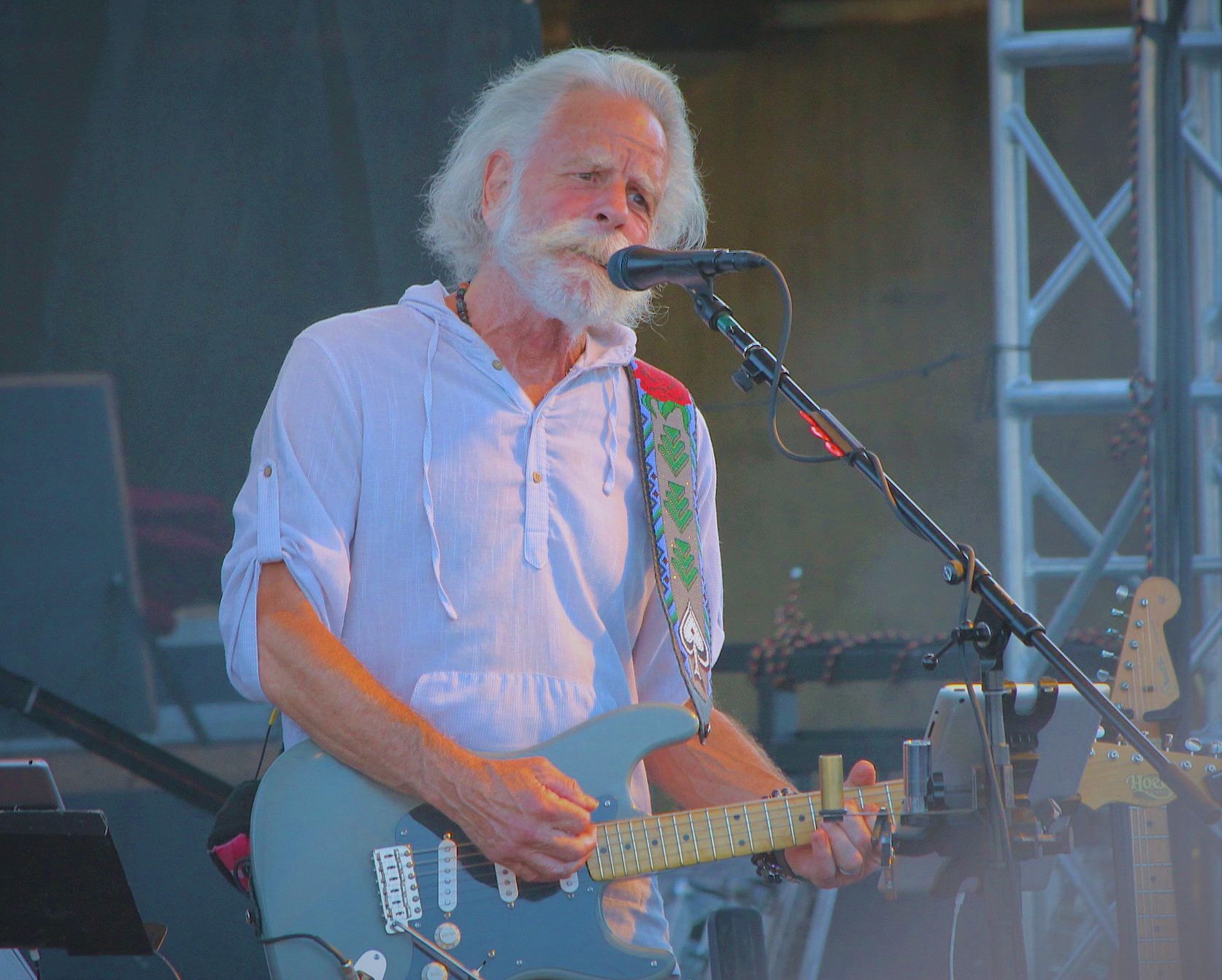

BM: Well seeing it all together in a book like this, and having people like Steve Parish and Tom Constanten be involved in writing a forward and preface gives me some sort of validation since I started off as a fan. It just evolved through the years. And also hearing nice things from Trixie Garcia and Bob Weir is nice to have, regardless of validation.

GW: Absolutely. And the book really is a gem for the fans and the band alike.

Blair Jackson’s introduction details your experience of first seeing the post-hiatus Grateful Dead and how it starkly contrasted your expectations from hearing rocking recordings like Skull-Fuck, Europe 72’ or Live Dead. Were you deterred from your hyper interest in seeing the band at the time?

BM: No. Because my first Grateful Dead related concert was seeing Jerry Garcia and Merl Saunders and some various Jerry Garcia Bands, like with Nicky Hopkins. That was two years prior to my first Grateful Dead concert. So I knew had good Jerry was live, but when the Dead came back in 1976, like I said in my introduction it just wasn’t the Grateful Dead I was hoping to see. I stuck with it. A year later in 77’ they were breathing fire. So it didn’t really deter me it was just a little disappointing at first.

GW: And it also wasn’t a time like now when you can log onto archive and hear any Grateful Dead concert you want.

BM: Yeah you get online and listen to just about anything these days.

GW: You have a true gift for capturing intimacy in the musicians you have photographed. It doesn’t matter if it’s a three hundred-person room or Giants Stadium; the observer still gets that same next to the stage side feeling. Could you recall two memorable experiences in photographing the Dead, a gargantuan venue and an imitate venue?

BM: Certainly. In terms of intimate venues, it probably didn’t get more intimate than at this club I saw them at in Amsterdam called the Melk Weg during their 1981 European tour. It was a very small room, maybe just a few hundred people. Getting up the front of the stage wasn’t too difficult. The cool thing was that ordinarily in their live shows at the time they didn’t stand to close together anymore. But in this particular club they were practically right on top of each other. And that provided me with a lot more band interaction to photograph. And a tremendous show, like say Giants Stadium in 1987 or 1989, I might take a different tact there. Like one really cool shot in the book, instead of being close and intimate, I wound up shooting from the upper deck. And I got this incredible view of hundreds and hundreds of people in front of the stage and the Dead playing for them. It’s quite the dramatic contrast from seeing them a few years earlier in Europe in a little club.

GW: By the mid-80s you were authorized by the Dead organization to shoot from the photo pit next to the stage, which was extremely limited access in those days. Your shots from the crowd previous equally stunning; the band against horizon and backdrop of Red Rocks Amphitheatre, or action shots like you just described. Did being close up change how you photographed the band?

BM: Not really. I still tried to cover the event from all angles. Like walking into the show. I wanted to cover the complete experience. Like waiting in line for tickets or something. For me the audience was pretty much as important as shooting the band. Although I had pretty primo access back then, it didn’t stop me from getting back into the house, and shooting from the audience point of view. Knowing that I could go upfront and get this close up shots gave me more latitude I guess.

GW: I find it interesting that though you traveled with the band all over, capturing their career from the mid 70s until current, but you didn’t move to the San Francisco bay area until the early 90s. Can you talk about the identity of being an East Coast Deadhead, and how those fans relate to the band differently than California Dead Heads?

BM: Yeah. I first visited California in 77’ right after I finished high school and I visited here a number of times in the 70s and 80s before my wife and I finally moved here in 1990. There is a stark contrast. I noticed it at the first show I saw living out here. It was at Shoreline Amphitheatre and the crowd to me seemed lethargic. Like they came out onstage and the crowd was like “okay, there going to begin.” Whereas at like Madison Square Garden in New York when the Grateful Dead entered the stage it was like thunderous. The building shook. Maybe having the band so close to home here as more of a locals thing. Not more special, just different. So East Coast fans are a livelier bunch I’d say compared to the West Coast. For me, moving here and seeing that eventually took some of my East Coast edge off. Twenty-five years in Marin County will do that to you [laughs].

GW: Nearly as vital as your shots of the band was your documentation of the eclectic Dead heads at concerts and in lot before the shows. What do these crowd and fan shots reveal about the Grateful Dead concert scene?

BM: I’ve been to lots of concerts, and bands have loyal fans. But the Grateful Dead’s relationship with their fans is like no other band. The lot scene, especially in the older days, people seemed to look out for one and other. Like that line from Scarlet Begonias, “Strangers stopping strangers, just to shake their hand.” That was real. I was alone at some shows were you’d get separated from your friends somehow and there was always people. You were kind of adopted by them. Welcomed into their inner group to hang with for the show. That’s the kind of things that separated Grateful Dead fans from other rock bands fans.

GW: While the Dead were always popular amongst legions of devoted fans, the biggest phenomenon of their career was the extreme surge of mainstream interest and popularity that came in the later 1980s, when selling out multiple night runs at 50,000-person football stadiums was the norm. Did the mega-Dead era effect how you photographed the band or the crowd? What changed?

BM: Yeah It got tougher. Those big shows always seemed to be in the summer and it always seemed to be hot out. You’d have to have a lot of stamina. The crowd was definitely at least at the East Coast shows became a rougher kind of crowd. People were quite as schooled. They weren’t “professional concert goers” as I liked to call it. Maybe there was more alcohol. It was definitely a harder-edged crowd. Security became more belligerent at some shows. I was at that show at Brendan Byrne Arena in 1989 when the poor kid Adam Katz was found dead after the show. The security was rough. It made life more difficult for everybody.

GW: It seems like it changed a lot about how the Dead wanted to do things.

BM: Yeah sadly gatecrashing became more prevalent.

GW: Quite sad. So lets flash-forward to the mid 90s. The loss of Garcia and the end of the band was crushing for so many. Live Dead details around the time of Garcia’s death the influx of media pursuing you for your decades of photo documenting both Garcia Band and Grateful Dead. It occurred to me that could have been a very powerful personal moment. Do you recall your emotions during that whirlwind in August 1995?

BM: Yeah. On that very day I was besieged by phone calls from media magazines. It was kind of bizarre. At that time to make photos to send to a publication you actually had to print them in a dark room. So I started printing some photos. Some of these publications such as Relix and a few other important ones needed these pictures. There were tears in the developer. Printing those photos. Being in a strange zone for those days. And then attending the memorial a few days later in Golden Gate Park. I had to be in Haight/Ashbury just to be around others.

GW: And also being inquired about business in a personal moment of grief and loss.

BM: It was strange. I had to deliver on some levels. I would have rather been doing something else.

GW: And it works both ways. The pictures you had aided in represented the band and their legacy.

BM: It was important that some of these things were out there for people to see and relate to. I kind of had to deliver.

GW: Understandably. So something interesting that I learned from Live Dead is that you are a professional graphic designer and that you contributed your art to the later covers of the Dick’s Picks archival release series. What inspired you to contribute what you did for the Dick’s Picks cover art?

BM: Well that was like a dream. Most people who do graphic design might fantasize about doing cover art for their favorite band. In the early 2000s that opportunity came to life. The person who was designing the covers had left and then I was introduced. I made a presentation to their management. They liked what they saw. I asked them “what kind of layout or design are you looking for?” and they told me to do whatever I wanted. Wow! A blank slate. It was kind of difficult. It’s good to get some guidance but I didn’t get any guidance. So I presented a variety of ideas for the Dick’s Picks series. And this was a time and idea that I poured my heart into because this was a client that I cared about more than anything else. It was an incredible experience. Being on the inside of those CD and DVD [View from the Vault series] projects back then.

.jpg)

GW: Perhaps more remarkable than the long strong trip, the 30 years of Grateful Dead with Garcia, is what’s happened since. So many different stellar bands featuring members of the Dead and just highbrow tribute projects. You are heavily involved in capturing what’s current in the ever-thriving Dead Head world in the bay area. What is your involvement with Phil Lesh’s Terrapin Crossroads and Bob Weir’s TRI Studios?

BM: Yeah. In the post Jerry years, I couldn’t have imagined back around his passing how things were going to play out. I was lucky to be involved with Phil Lesh and Friends right around when he started playing again around 97’ at the Maritime Hall in San Francisco. I was introduced to them. I had great access and photograph. And that’s now been going on for years. And then a few years ago almost simultaneously Terrapin Crossroads and TRI Studios opened up, and additionally the [reopened] Sweetwater Club in Mill Valley. That provided a kind of musical renaissance in Marin County where it’s like music seven nights a week.

So at TRI Studios I was hired to be their staff house photographer for about a year or so. And being there for that time I shot some amazing stuff. The things they have there aren’t usually open to the public, it’s kind of an invite only sort of thing. It’s a small room; maybe a hundred people most could be there for certain events. So I was very fortunate to get to be involved in that and to also shoot events at Terrapin Crossroads. I’m also the house photographer at Sweetwater, which affords me opportunity to capture and document almost anything that comes through in the Bay Area. I’m honored and blessed to be part of it.

GW: It’s a wonder how it’s developed since. People my age can still live that feeling through these continuing projects. For my generation it’s a blessing in a totally different way.

BM: And it’s that way for people my age too. With Grateful Dead, if you don’t carry the baggage with you. [Laughs] And there are fantastic bands that have since carried the torch so to speak. Bands like New Monsoon, ALO, Mother Hips and Moonalice. In their own way they hold that similar vibe. And it continues on which I’m really happy about. For the book, I really didn’t want it to end when Jerry passed so I did devoted a number of pages for the post Jerry years with sections on Terrapin, TRI, and Sweetwater. The books dates till up to this year.

GW: And many casual fans that buy your book might not have known what was going on since the Grateful Dead disbanded.

BM: Yeah its interesting some people that I know who aren’t particularly Deadheads bought the book because it’s a cultural history. It’s part of Americana. Culture of the 70s and 80s that was reminiscent of the 60s. It’s interesting and I would enjoy knowing that not only hardcore fans will buy this book.

GW: Absolutely. And this book is really a milestone not only for you but also for the entire scene since its essential archival photography on the band.

BM: Most of these 700 photos haven’t been seen by people. Some of them might have been published in Relix along the way. As a fan it’s a way to discover hundreds and hundreds of new photographs of your favorite band. For people who follow this I hope its pretty mind blowing.

.jpg)

GW: Your gift to us! I want to encourage our readers and listeners to go out and get a copy of Live Dead for their own sake. Just to gaze upon these photos. No doubt that this book will further contextualize the Dead as the iconic American rock band and beautifully represents their close relationship with fans and insider media personnel.

BM: Yeah absolutely. It’s been a pleasure talking to you!

To buy an autographed copy of Live Dead directly from Bob Minkin, please visit his website, http://minkinphotography.com/livedead/