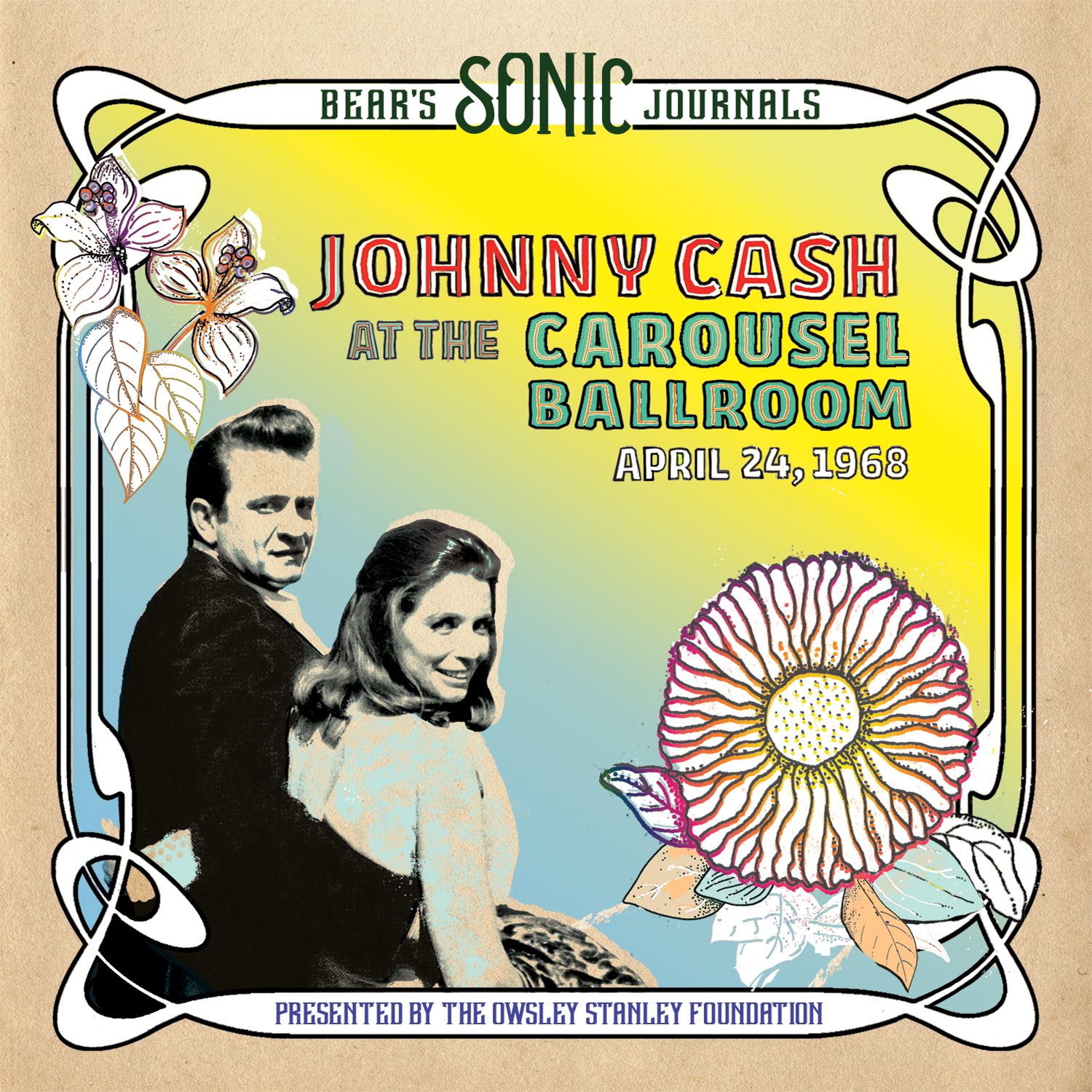

As another new year rolls in, I can’t say how excited I am to see the Grateful Dead family not only thriving but flourishing. We Deadheads can take pride in having become a borderless, boundless global community where a simple Steal-Your-Face sticker on your pack and a smile will find you a safe haven. And with thankfulness being one of the defining criteria of a Deadhead for the life-changing, enlightening experience the Dead brought to our lives, we have a healthy desire to express that gratitude. What is “it” we’re so thankful for? Well, the list could be long or profound, or simply musical, but whatever “it” is, it will be gathering at the Skull & Roses Music Festival in Ventura, California, April 2nd - 5th.

And as thankfulness and appreciation spring eternal, with my deepest sympathies and respect to Robert Hunter’s recent passing, I’m sure this shall be a very special Skull & Roses for us all.

A family reunion of odd sorts, Skull & Roses is a place where we Deadheads can appreciate the musicians and people we have become and attracted, be ourselves, and commune with our people in celebration of the Grateful Dead and the Deadhead community— something that holds a dear and special place in each of our hearts, for what would life have been without?

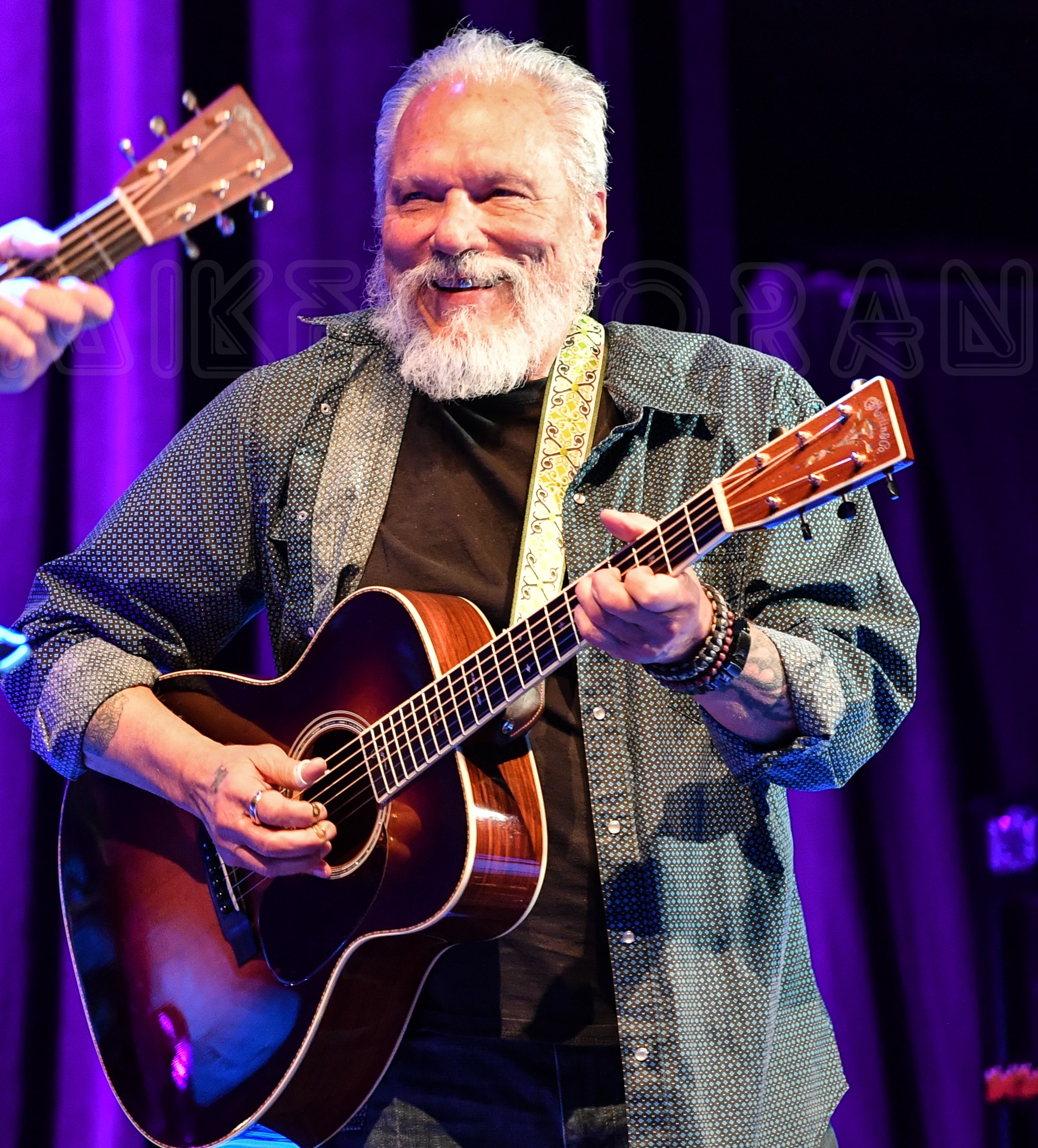

This year’s festival brings together a multitude of bands and musicians who have jumped on the bus over the years, each happily taking up the mantle, declaring, “St. Stephen will remain.” The list spans the years nicely, included among many others, Kreutzmann with Billy & the Kids, Oteil & Friends, Melvin Seals and JGB, David Nelson, Keller Williams, Ghost Light, Jackie Greene, and Jeff Chimenti with Steve Kimock and George Porter Jr. in Voodoo Dead. A gathering to behold!

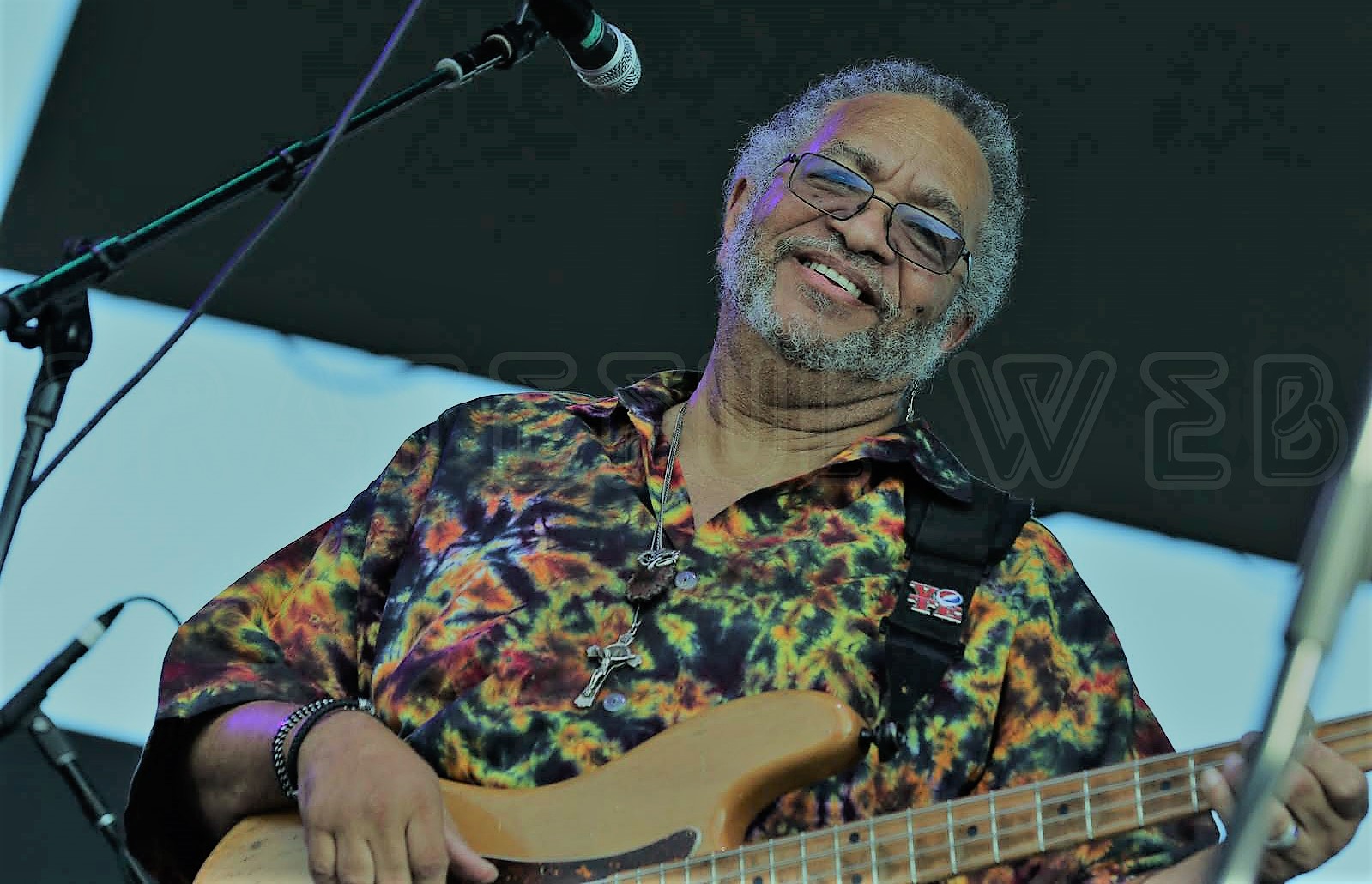

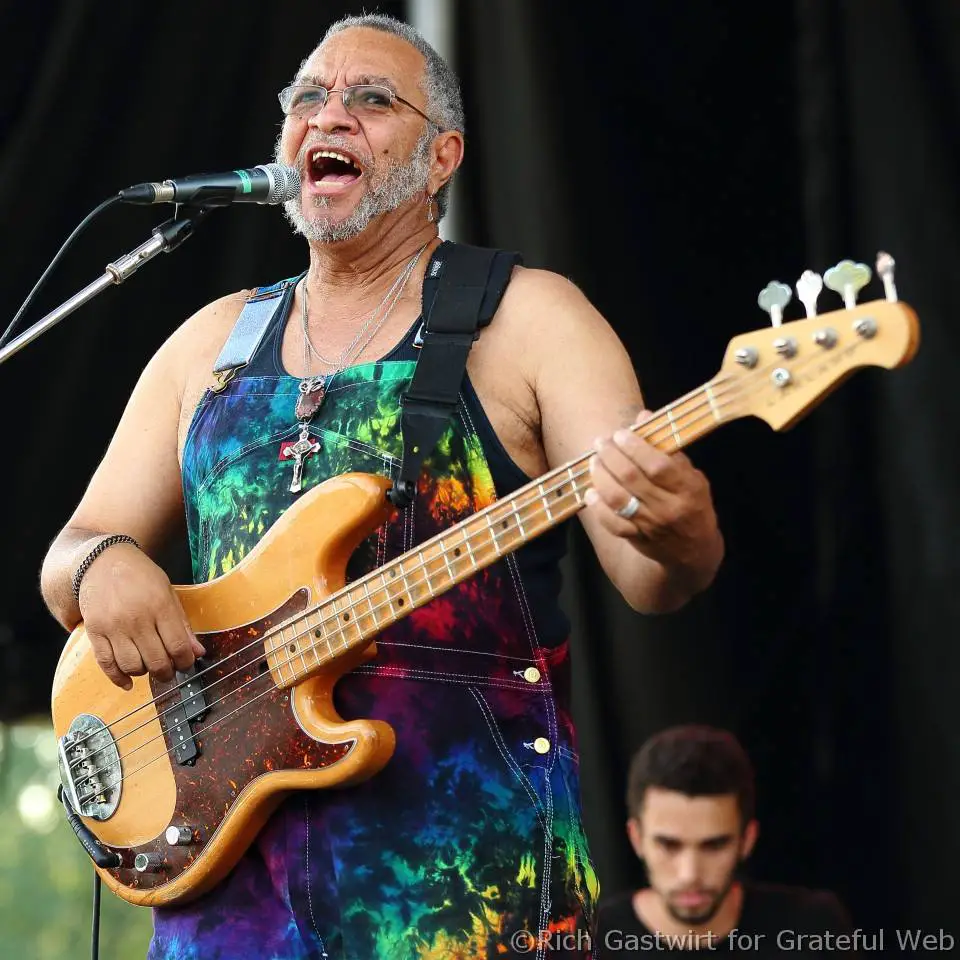

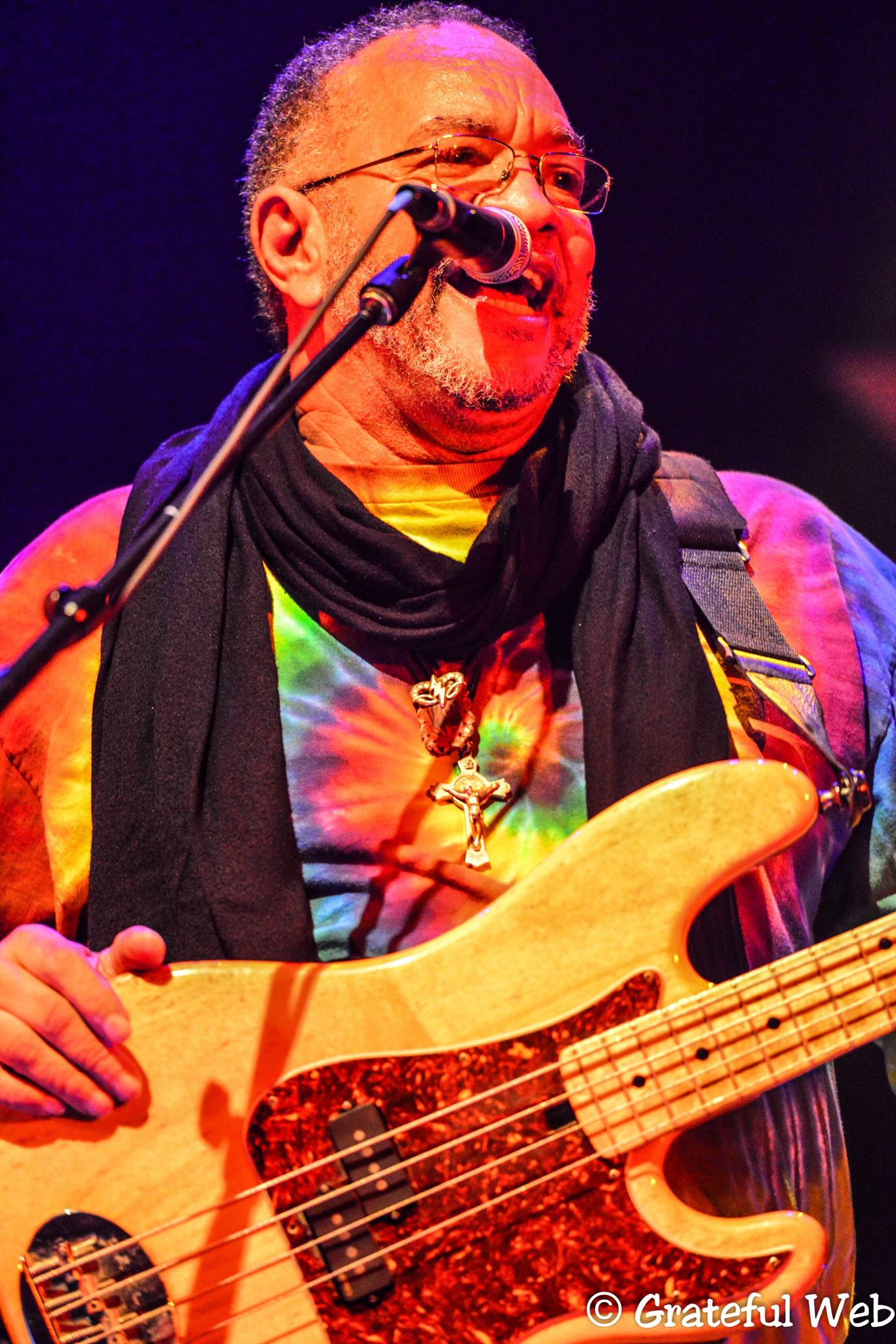

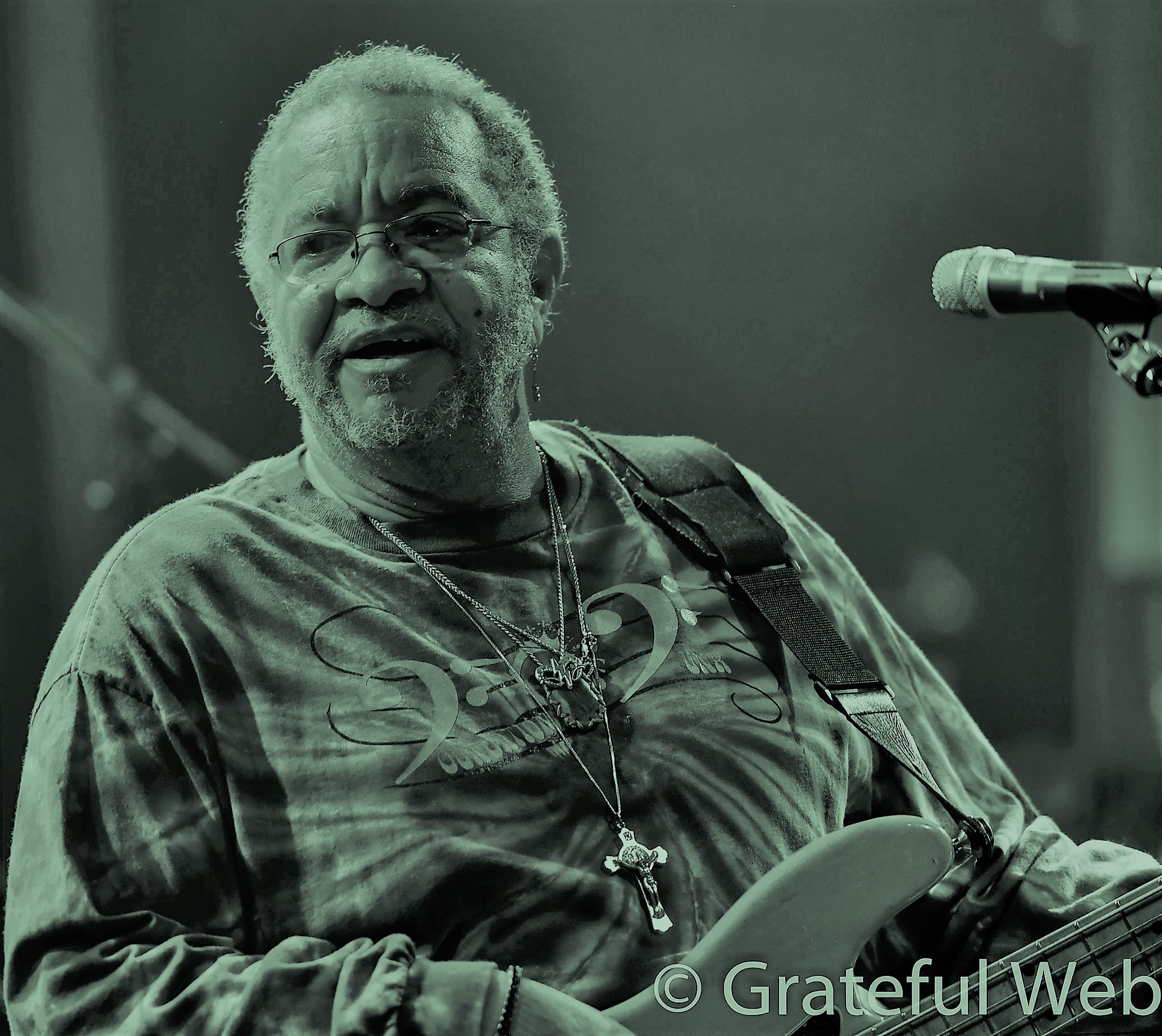

And when the Dead, in all its forms, invites someone into the fold, people take notice, for we know they are worthy of our attention. And lately, it’s been George Porter Jr., a tie-dye clad, all smiles, funk, R & B bass player from New Orleans. Starting out in the ’60s with a simple placard, “Have bass, will travel,” George Porter Jr. was already a Deadhead at heart and has gone on to become one of America’s finest bass players. From a young age, George’s willingness to learn, listen, and play with any and all led him to more mature and talented players, each leaving their imprint ingrained. His humble philosophy of being “who you need me to be,” when it comes to playing, led Porter through a plethora of experiences, top-level musicians and times too many to even imagine, ultimately shaping whom one day would become the recipient of both the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and “the nod” from the Grateful Dead.

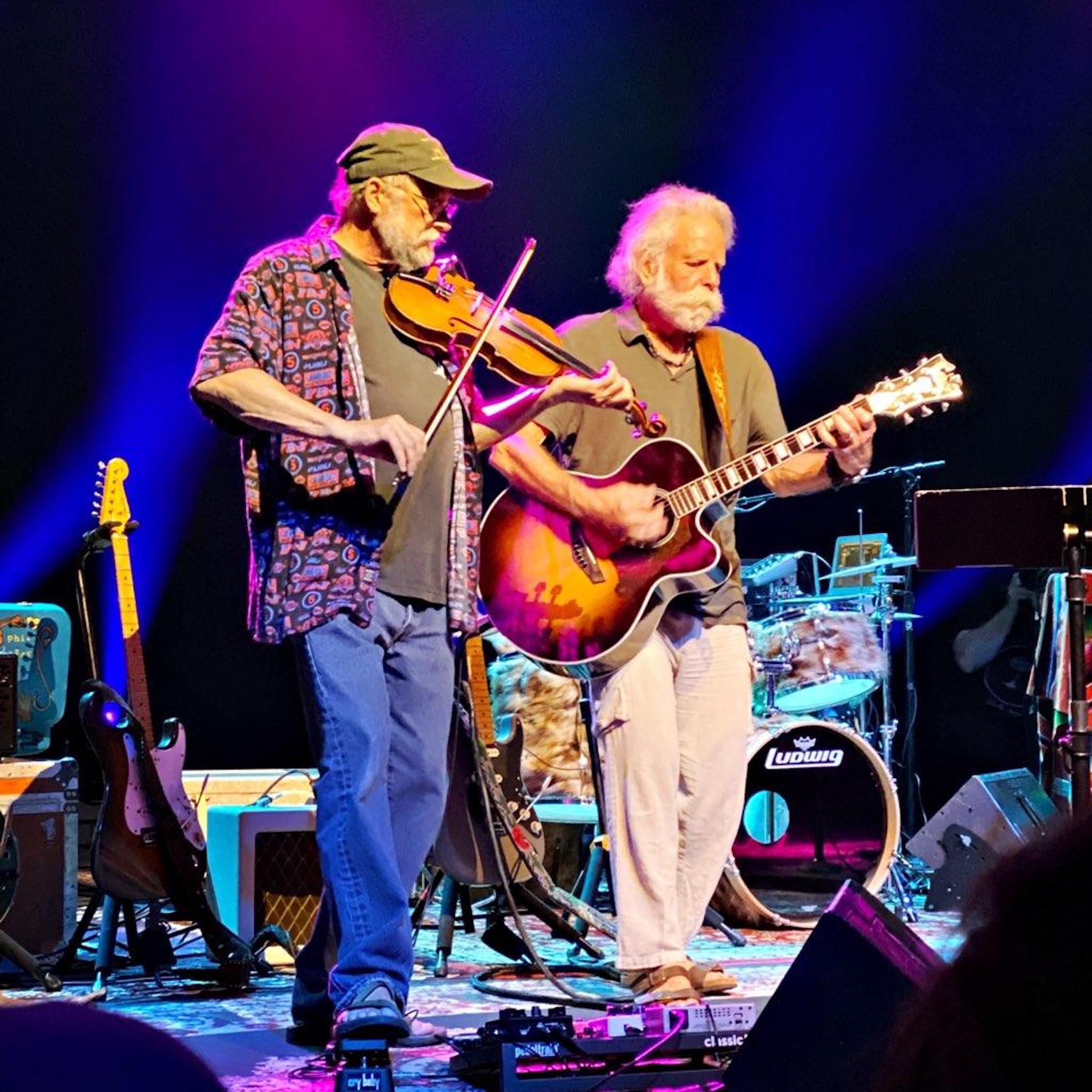

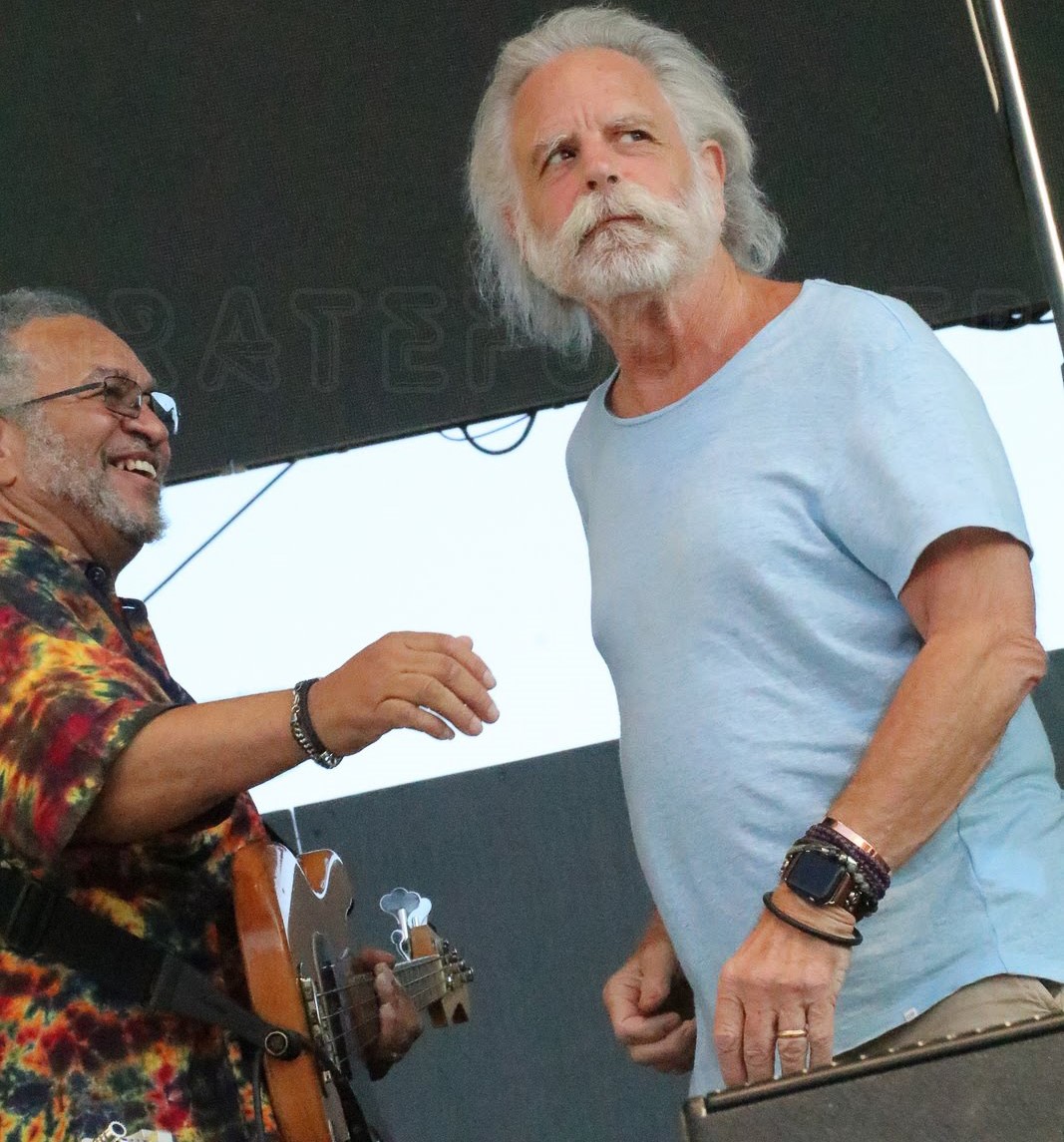

While predominantly recognized from his work with The Meters and his funk sound of the seventies, George’s current bands, The Porter Trio and Runnin’ Pardners, as well as his work with Bill Kreutzmann, Bob Weir, Dead & Company, and Voodoo Dead represents some of his hottest shows and finest playing to date. He’s got some truly smokin’ stuff out there people! And a lot of it.

With Skull & Roses just around the corner, Grateful Web caught up with George to talk all things Dead and then some.

GW: Hello, George. Great to get a chance to talk with you.

George: Yes, my pleasure.

GW: I’m sure you’re aware that the Skull & Roses festival is a celebration of the Grateful Dead and the Dead community. I was wondering what your impressions were when you were first introduced to the Dead family. I know with most Deadheads it was a rather significant event.

George: I’ve always been much aware of the Dead community. I mean, I probably knew some deadheads, as some of the hippies I knew were probably Deadheads. I guess I don’t know exactly how you’d put it. [Laughter] But I mean, I remember wearing bell-bottoms and tank tops and stuff like that back in the middle seventies, early eighties. I wore hippie clothes, but at that point in time didn’t really know what the Grateful Dead was. I had heard of the band before, but not knowing any of the members or even hearing any of the gigs. Then I guess in the eighties, when the Neville Brothers— they started playing dates with them after The Meters had broken up— I got to hear more about the Grateful Dead because of the Neville Brothers involvement with them.

I think my original exposure was my very first time meeting Bill. I was playing a gig Saturday evening at a little club in New Orleans called Les Bon Temps and Bill came in to play. Well, Bill was just hangin’ out actually and one of the guys that was with him told the drummer that Bill wanted to sit in. I think the drummer then was Kenny Blevins. He was told that Bill Kreutzmann was in the building and he’s the drummer for the Grateful Dead, and he wanted to sit in on a New Orleans’ kind of song. So I think . . . that happened and “Iko Iko” was the song that got called. But the way Bill played it was not the way John Mooney conceived it to be. Then, you know, he was a little embarrassing because he kind of stopped the song and gave Bill some grief about it, you know, “Where you learn how to play?” [Laughter] And I remember Bill leaving the stage, like, “Ah, man . . .” And I thought, “Who’s this guy?” [Laughter] While I didn’t feel worried, I was sitting there going, “Hmm, my God, John was out the box.”

It wasn’t until Steve Kimock brought me into Mickey Hart’s band that I learned any of the music. At the time, I had to learn some Dead songs as well as some new songs that Robert Hunter had written for Mickey’s solo project. But like I said, that was a short-lived outfit. I think that Mickey only did that particular band on one little short tour, I mean, probably like three or four weeks, something like that. And then, two years later it was the 7 Walkers project.

But let me answer your question about the size of the community. No, I didn’t really even start figuring that out until probably nine or ten years ago when working with Bill and Mickey and then being asked to perform. I started getting calls from other bands that performed Dead songs to play in those bands. I believe it kind of started coming together from my version of “Sugaree.” [Chuckles]

GW: And that’s how you became a Deadhead?

George: Well, it had to do with income. [Chuckles] You know, I’m a bass player for hire. So the old saying is, “He who pay, I will play.” [Laughter]

GW: Did your style of bass play fit in well with Bob, and Mickey, and Bill, and Dead & Company?

George: I brought a totally different feeling to the songs. Originally when I first played with Mickey Hart’s band, I went out on that little short tour with him. I didn’t think I would ever hear from them again because I was not the type of bass player that Mickey was looking for—although Steve Kimock kind of put my name in the hat, and still does. I was more of a pocket player than a melodic player, and so I didn’t think that fit well. But then, a few years later when I got to play in the 7 Walkers with Bill and Papa Mali, Bill loved the pocket. I mean, Bill was more interested in being in that pocket and he was very happy with where I was at. We play really well together.

Then Bob Weir sat in on a gig I played at Christmas Jam with Eric Krasno, Bradford Marsalis, John Medeski, and Terrence Higgins. Bobby liked what he was hearing from where I was at and asked me to sit in with his solo project at the Saenger Theater in New Orleans. So when Dead & Company asked me to come sit in with them on that show in New Orleans, it was kind of a natural fit.

GW: Yeah, I really enjoyed that. I’ve watched it a few times. Smokestack Lightning was a great pick.

George: I like to think I’m the kind of bass player that can play the gig. If the gig requires a certain thing, I can leave me at home and be what the gig calls for. I’ve become a little bit more of a melodic player than I was originally, but I’m still more a pocket player.

GW: When I looked back on your life, I couldn’t fully fathom how many times and stories you have. How has such an accumulation of experience influenced your music? Can you even articulate that?

George: No. I think it goes to say, like I was saying earlier, when you hire me to play your gig, I have been able to leave a great deal of me at home and be what you need me to be to perform. I’m pretty good at being that bass player that’s needed for that particular project. I just think I do that very well. I’m that bass player, I can be whatever you need me to be.

GW: You leave yourself home for them and give them what they need. What if we were to spin that around and rather than what you offer them, talk about the impression their music leaves on you?

George: If it’s musical, I’m cool with it. I’m not just going to go play a bunch of crazy stuff. I think there’s very little just absolutely crazy stuff out there. I think I get to play music with good musicians and good players, and so I don’t feel like I’m selling out to do something. I mean, if I hear the music and the music is horrifying, then I turn the gig down. [Laughter] I have done that.

GW: And now you’re about to head out to Ventura, California and hang out with a bunch of hippies.

George: Well, I mean, I’ve been hanging out with a bunch of hippies since probably the last ten or 12 years now. I believe that I have found a nice spot in the Dead community. A lot of the Dead guys introduced the Deadhead community to a great deal of New Orleans music. So people hearing me play with those guys has been somewhat natural.

GW: That it is. The Deadhead crowd is a huge community to introduce your music to, with hundreds of bands playing their music. The Dead have had quite an effect on America and the American music scene.

George: Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely.

GW: When you go to these music festivals do you guys play backstage together at all?

George: Not usually, unless we are rehearsing. I don’t hang out much as since I got sober I kind of got boring. [Laughter] So at all these music festivals, there’s lots and lots of pot smoking and stuff around, so I kind of like go and do what I have to do, and I’ll kind of get out of the way, you know? [Chuckles] Just because I’m doing a concentrated effort to protect my sobriety.

Sometimes at big festivals, things just happen. I think it was the Lockn' Festival last year that Foundation of Funk played— that was Zigaboo, Tony Hall, Ivan Neville, Ian Neville— and at first we heard that Bill was coming out to sit in with us . . . and then the next thing we heard was that Mickey was coming, and Bob Weir was coming, and John Mayer showed up too.[Chuckling] It was almost the whole Dead & Company band, they all showed up. We all ended up on stage playing together for about four songs, about the last twenty minutes of our set. It was fun!

GW: And that’s just one of the special stories that make up your career. I can’t imagine you don’t have a million stories like that from fifty-plus years of playing.

George: Oh yeah, there’s quite a few times that things surprise me, but I don’t believe anything that surprising has ever happened before. Not in my lifetime. That was an absolute first.

GW: I bet that woke up the little boy in you, huh?

George: Yeah. [Laughter] When I started seeing the guys bringing guitar amps, then more guitar amps were coming out to the stage, old percussion rigs was coming out, and so before you know it, we were like a nine-piece-something band.

GW: You spoke of trying to protect your sobriety. How do you keep your energy up for all this touring and traveling? Are you drinking a bunch of Red Bull? Or are you eating your vegetables?

George: I kind of go to bed at night, I sleep. I was drinking Red Bull for a while, but then I had to stop doing that because my stomach wasn’t liking it very much. I couldn’t take the acid and all that sugar. It pretty much turned out unhealthy. So I stopped drinking the Red Bulls, and I just started getting rest and eating vegetables, and just trying to think healthier.

GW: Yeah, it seems the modern-day buzz as we get older is more like a smoothie instead of a beer. I think I get a better buzz from a smoothie these days. I don’t have the bounce back with beer that I used to.

George: Yeah, I don’t see too many smoothies around on gigs too much. But yeah, I guess a good smoothie drink would be nice too.

GW: Get all your fruit and vitamins. We never thought to try health when we were younger. What a novel concept.

George: [Laughter] Right, right, right.

GW: Melvin’s going to be playing at Skull & Roses this year with the Jerry Garcia Band. You’ve been playing with him some as well. I was curious as to how you met Melvin.

George: I don’t remember exactly how or when was the first time I met him— it’s been probably at least 20 years or more in San Francisco— I don’t really remember how and when that happened but I think I met Melvin when he was asked to sit in with my Runnin’ Pardners band at the Boom Boom Room a long time back.

GW: You guys do go back a couple of decades anyway?

George: Oh yeah, absolutely, absolutely. And then Melvin always tells me that he’s a big fan of The Meters and the New Orleans thing every time I see him. He’s always speaking highly of the guys in the band. You know, Zig and Leo were both living out there in California for a long time, so he got to see them more than he got to see me.

GW: You definitely have a big Meters’ following. There’s a bunch of top-notch people that speak very highly of the band. How was it playing in The Meters when you first started out in New Orleans? You were a bar band, weren’t you?

George: Oh yeah, absolutely. That’s where we started out playing in nightclubs, in a club called the Night Cap. Then we moved from there to the French Quarter and played on Bourbon Street for a good year and a half the first time, and then maybe five or six months the second time. After they released the “Cissy Strut” and “Sophisticated Cissy”, we went out on the road, and then came home and went back in the studio. While we were back home, we went back on Bourbon Street and played at a club called Ivanhoe. I think the fact that we had almost three years of playing as a unit before we ever became The Meters had a lot to do with the reason why Allen Toussaint kind of sought us out to become his in-house studio band.

GW: How is it that you guys ended up getting the moniker of being the Fathers of Funk? Was it something as simple as being musicians at the time the wah-wah pedal came out?

George: I don’t know how that came about. All of us individually were individual musicians. And I think we all kind of listened to different music.

So I believe the wah-wah pedal got introduced to Leo through somebody else. I’m not sure who. I remember one time I used to use a wah-wah pedal on my bass until I discovered a thing called Neutron which gave me the same effect as a wah-wah pedal would give me but it was an envelope filter. So I moved away from the wah-wah pedal and started using this envelope filter, which I still use at my gigs. Not the Neutron, but I still use an envelope filter made by EBS.

GW: Was the funk sound something that was around you guys at the time? Or were you somebody who was really pioneering a sound that everybody would go see and say, “Wow! That’s something different,” or hear you and go like . . . “What!?”

George: I can’t answer that question. We were labeled funk. It was a sound that just came out of four musicians with different backgrounds coming together. I remember when I wasn’t playing with those guys, I was going and listening to jazz and jazz musicians. And the jazz players that I listened to were, um . . . well, they weren’t strictly jazz, they were R & B. They were, um, I don’t know how you put that. Well, let’s put it this way, when I was fifteen years old, sixteen and seventeen, I was playing with different bands or beginnings of bands and to be in the action, to even work in the sixties in New Orleans, you had to know how to play everything. You had to know how to swing, you had to know how to play a shuffle, you had to know how to play the blues. So, you know, it was important that you were well rounded as a musician. So I always may have accredited myself as a well-rounded musician. I can play anything. Once I put my mind to learning how to play it, I’ll play it. And then, I have my motto, “He who pay, I will play.”

GW: And hence, that’s how you played with just about everybody.

George: [Laughter] I like that.

GW: How do you get that well rounded by sixteen years old?

George: I was playing with musicians that were ten, fifteen years older than I was. I listened. I listened. I mean, it was almost probably . . . seventy-five, eighty percent of the songs that I learned in the sixties, I learned at the gig. You know what I’m saying?

We had radios in the house. My dad listened to a lot of jazz. My mom listened to R & B. She was into R & B and blues. Things like that. We listened to a lot of New Orleans and local music back then. We had radio stations in New Orleans, even the white radio stations in New Orleans played a lot of the black R & B musicians and music. So the radio stations in New Orleans weren’t so isolated. Yes, they played rock and roll music, yeah, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis Fats Domino, and local guys like Earl King, Irma Thomas, Raymond Lewis, stuff like that. They would play all those guys.

GW: That kind of background, ear, and improv seems to have set you up perfectly for the Grateful Dead.

George: It set me up perfectly for, “Have bass, will travel.” [Laughter]

GW: And you’ve done a lot of travel.

George: I have a great feeling for music, all kinds. I mean, the only gig I haven’t gotten at this point is a country and western gig. I told Ashley Judd, Wynonna’s little baby sister, to let her know that I’m available.

GW: [Laughter] Need to play that card still, huh? I’d like to hear that.

George: Huh, what do you mean? [Laughter] I’ll give it a shot.

GW: Hear that Wynonna! So, who will you be playing with at this year’s Skull & Roses?

George: Voodoo Dead. That’s with Steve Kimock, I believe his son John Morgan Kimock, Jeff Chimenti, and I’m not sure who the other guitar player is. There’s usually a second guitar player that does most of the lead singing. Yeah, Voodoo is Greene, Jackie Greene has been that band. Last year we played with Al Schnier.

GW: So you’re going to be winging it once again, huh.

George: Oh yeah. [Chuckles] Though not really. We will have time to rehearse.

GW: When you’re playing with the Runnin’ Pardners or the Porter Trio . . . or even the Funky Meters . . . have you thought of sneaking a Dead tune into the middle of your crowd?

George: Oh, I do, not necessarily in the Runnin’ Pardners but in my Porter Trio, which is two of the members of the Runnin’ Pardners, the keyboardist and the drummer . . . and myself. We do “They Love Each Other.” We do, “Eyes of the World.” We do, “Sugaree.” Everybody always accredited “Lovelight” to the Dead, but I have been playing it forever as it’s a Bobby Bland song from the ’60s.

GW: With the recent passing of Robert Hunter, this year’s Skull & Roses festival is going to be rather special. Do you have any thoughts on Hunter as a lyricist?

George: I thought, when I happened to learn some of these songs, I said, “Holy shit! They got a lot of words here.” [Laughter] But I thought all of them were all great stories. Some of them I didn’t quite understand. I even asked Bill, “What’s ‘Sugaree’ all about?” I asked him about it, and he say, “I don’t know.” [Chuckles] Nobody in the band was able to tell me what the song “Sugaree” is about.

GW: I thought it was about a girl who gets busted, and she can shake it all she wants, but don’t tell on me, man. But now you have me wondering.

George: [Laughter] The one thing I do know, it was about a girl or maybe a drug dealer.

GW: Ah, that’s funny. You know, you look at things like “Eyes of the World” with these great lines, like, “Wake up to find out that you are the eyes of the world, you’re the song that the morning brings.” This is the thing Deadheads attach to. It’s this philosophy Robert Hunter introduced that brought cohesion to the Grateful Dead’s playing— so Jerry Garcia’s guitar could take us somewhere— because we had a lyrical concept in our head to release us to a larger understanding of things.

George: I’m a big fan. I really like, “Eyes of the World.” And I’ve been liking, “They Love Each Other” too. That’s a beautiful song. I’m thinking sort of Voodoo Dead playing— I’m thinking about learning, “Black Muddy River.” I’ve played that a few times with other people singing it, and I’m not that crazy about the way they sang it, so I’ve been thinking about putting my try in, seeing if I can wrap my vocals around that one.

GW: I’d love to hear that, as I’m sure many others would. I wish you success there. I know a few years after Jerry passed away, the Persuasions put out a Grateful Dead album, “Might as Well,” all A cappella, and I believe they did, “Black Muddy River” on that. Great album. Worth listening to.

I could tap you all day for stories, George, because I know you have a million of ‘em. And I have to say, it’s been a great honor getting a chance to chat with you. I’m definitely a fan. Which, I guess, brings me to Art Neville. With his recent passing, as more and more people fall away, I was wondering if you had anything to share about him and your relationship.

George: Well, I woke up this morning knowing that today was his birthday. He would have been 83 years old today. I think he’s eleven years older than me. The day after Christmas I’ll turn 72. I was just wanting to call him and wish him a happy birthday, but the phone where he’s at don’t ring. That was kind of that lost feeling. I kind of woke up with that lost feeling that he’s not around anymore.

There’s so many of my good— so many of the guys that I kind of accredited as being part of my growing up in the music industry, there’s only maybe one or two of them still alive. Yeah, there’s probably one or two of them, maybe three. One of them I see every now and then. Two of them I haven’t seen in twenty years. I know they’re around because I see their names on Facebook. But mostly the guys who I’ve been playing with, oh, for the last 20-some-odd years, 20-plus years, with the Runnin’ Pardners, has kind of been the center of my world, you know?

The young players that have come into my life over the last few years, maybe the last ten years, the youngest player, Terrence Houston, is the new drummer for Runnin’ Pardners. By new, I mean he has been with me for 10 years. [Laughter] He is also the lead drummer for the Porter Jr. Trio, and he was the last drummer for the Funky Meters, taking over when Russell Batiste retired from the band. Chris Atkins is the newest member with two years in as the guitar player, taking over when Brint Anderson retired from the Runnin’ Pardners after playing in the band for 27 years. The young players that’s coming into my life are bringing back some of the music I’ve forgotten about. [Chuckles] This is a great story. Chris just came on, and we played a gig somewhere in Georgia. After that gig, the Trio was going out to finish touring— we had a few dates past that so Chris rode back to the airport with my girlfriend— and he mentioned to her, he said, “You know, Porter should start playing some more of these songs. These are some great old tunes, man. I would like to get him to play these songs.” So it wasn’t three months later that I asked him— you know we were in the band the Runnin’ Pardners— I said, “Chris, why don’t you write the setlist for the night.” He said, “Really!?” I said, “Yeah, man, why don’t you write the setlist for tonight.” So he wrote the setlist out, and— oh my God— we only knew three of the songs on the setlist. [Laughter] I was like, “Oh, ho ho ho ho ho. Oh my God. Wow, Chris.”

GW: You weren’t already on stage were you?

George: No, no, no, no, we were still in the van. We hadn’t gotten to the gig yet.

GW: Oh, good! I could see you guys standing there on stage, going, “Okay boys, we’re winging it tonight.”

George: [Laughter]

GW: Just a few months ago, my wife’s grandfather, who’s 94, was telling me stories about being a kid and growing up in New Orleans in the thirties and forties. It’s a city with a fascinating history, with a deep heart in music. Have you seen that the music overall these fifty, sixty years has grown in good directions in New Orleans? Or has it started to deteriorate at all?

George: It has grown. It has taken on somewhat of a different picture from when I was a kid. I don’t know how you’d say, it’s, um, it’s modulating. The young players that’s coming into the music, they’re changing it to fit them, you know, cuz every one of those kind of bands— there ain’t too many bands in New Orleans that only want to be like the old band, like The Meters or somebody. They got a lot of young bit players in New Orleans that want to be their own Meters, you know? They want to be the next band to come out of New Orleans and be big. So, with that being said, I think that the music is taking on a new face. And the pockets are changing somewhat too, as well. It’s still good. There’s still some good players down here. And this city has always been great for drummers. I mean, we turn out drummers like crazy down here. There's always great, wonderful drummers coming out of New Orleans. That has not changed at all.

GW: Upcoming musicians often wonder how people get discovered. Was it random luck that brought The Meters about? Because the next thing you know, you’re touring with the Stones.

George: Well, we got to tour with the Stones through Ron Woods. When Ron joined the band that particular year, 1975, the Stones released that they were going to do a US tour. Ron Woods said, “Man, we ought to get The Meters to play some of these dates with us.” And Keith was open for that. So it kind of happened. We didn’t get to open the whole tour. I think we only did sixteen of those dates that they had in the US.

GW: So just the fact that Ron Woods had heard of you brought you in, huh? Well, and obviously you were that good.

George: Europe was very aware of The Meters. We played in Europe in the late sixties, very early seventies. We took a New Orleans contingency from New Orleans to play in London, and I want to say Switzerland, at Montreux Jazz Festival. The tour that we were on had The Meters, Professor Longhair, Dr. John, . . I don’t remember if Allen Toussaint was on that . . . maybe he wasn’t. It was supposed to be Snooks Eaglin too, but the morning that we were leaving, at the airport, Snook’s wife decided that she didn’t want him to go. And Snooks didn’t make the tour. We went over there and were well received. So they knew about us over there in Europe.

The night we played in London, after the end of our concert, all the New Orleans and British bands, we had a meet and greet with all those guys. Everyone from Rod Stewart, who at that time was in the band Faces. Ron Wood was actually the bass player in Faces at that time. Then there was Paul McCartney and Linda there. There were some great photographs of Paul, Linda and myself from that particular tour. But then, I lost all those photographs in hurricane Katrina.

GW: Oh, that’s too bad.

George: But it was great! We also met all the Stones that night. We met Procol Harum. We met all of the British Invasion. They all came. We met every last one of those bands.

GW: What a night that must have been.

George: That was actually cool. The meet and greet, all things possible. [Laughter]

GW: Was that tour quite the party or were you guys serious back then or both? That seems like a lot of people on the fun train.

George: It was both. I believe the promoter that brought us over there was hoping that it could be something that he could do on a regular basis. But I can’t go into any kind of details about why it didn’t happen again. It could have been as easy as saying everybody just wanted their own band, you know? That’s probably what it is. The Meters were like the house band. We played behind everybody. So I think Dr. John wanted to go back with his own band. Professor Longhair wanted to go back with his own band.

In Switzerland, when we played Montreux, it wasn’t a great night musically for Professor Longhair because they had an open acoustic piano on stage mic-ed and there was too much of the electrical instruments going through the piano . . . so they had trouble. The Meters ended up, well, we kind of got booed off the stage because the people couldn’t hear the piano playing and there was lots of feedback. They got upset about something we just had really no control over, making that acoustic thing happen correctly. If he had just closed the top, the lid of the piano, instead of making it look pretty, then it probably could have worked out a lot better.

GW: So you’ve been booed more than once.

George: [Laughter] Yeah.

GW: Ah, that’s just great. Just great. How did your show go last night?

George: Last night? Oh, last night was wonderful. It was a good night. Great turnout. And the Saints had won their football game. And when the Saints win their football game, the Maple Leaf goes crazy.

GW: That was an amazing performance. Breeze missed just one pass. The Saints have come a long way. I remember watching the Saints with a bag over my head when they were the ‘Aints.

George: [Laughter] Yeah.

GW: Did you end up losing your house in Hurricane Katrina?

George: No, we didn’t lose our home. It got drowned. The first floor of the house got four and a half feet of water. My mom’s house had nine feet of water in it. But one of the beautiful things about my mom’s house— her house was over a hundred years old and the house is built with cedar— so when they opened up the walls, that house was flexing its muscles, saying, “Give me some more. [Laughter] I want more of this stuff.” Because of the cedar, there’s no black mold.

Speaking of the maple Leaf, I’m gonna have to run because I gotta go get my gear out of there. Last night it was storming down here. I didn’t take my gear out of there last night.

GW: You bet, George. Thank you for being so generous with your time and sharing your stories. I look forward to seeing you at Skull & Roses and any other performance of yours I’m fortunate enough to catch.

George: Thank you. Bye now, and have a wonderful day.

“The bus came by and I got on, that’s when it all began.”