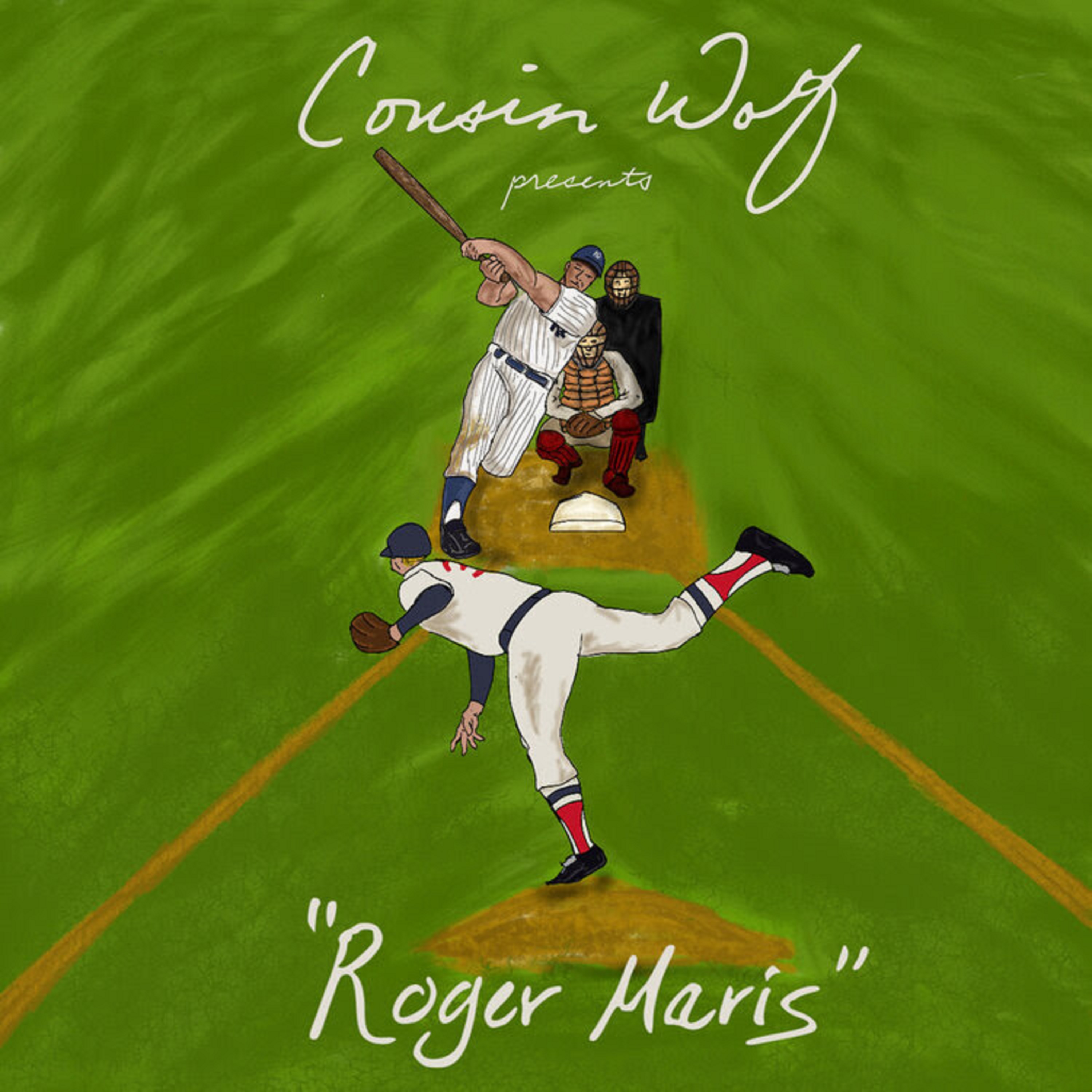

Opening Day for the Major Leagues came and went this year as usual, but this season we are gifted a 9-song release from Cousin Wolf aptly titled Nine Innings. Its a collection of tales about former and current Major League players. Below is a description about the project from Cousin Wolf himself:

"Nine Innings" is a collection of nine songs about current/former big-league ballplayers. Baseball is a beautiful game rich with stories to tell, and baseball is the lens through which I learned about the world as a kid. So, these songs are about baseball in one sense, and about understanding life in another sense, and with each song I tried not to just sing a biography but to embody the player at a particular time in his life. Through Roger Maris and Donnie Moore, I processed my own anxiety and depression. Through Carl Mays and Lou Gehrig and Jurickson Profar, I examined my own mortality and the endless cycle of life. Through Moses Fleetwood Walker and Jackie Robinson, I learned more about what it means and has always meant to be a Black man in America. Through Dave Dravecky and Kevin Elster, I considered what it means to face the loss of something you cannot bear to lose. Through it all, I tried to use these folk tales to uncover and discuss things deeply personal to me, and to share a few of the many "baseball" stories that transcend the game.

A Baseball heavy release to be sure, but you don’t have to enjoy the sport to appreciate the music. So far 2 singles have been released from the project, “Kevin Elster” and “Roger Maris”. With a singer-song writer element to the style of music, Cousin Wolf does add some flair with trumpets, and insanely addictive melodies. The lyrical delivery feels less like a history lesson, but a story that could be applied to anyone. Below is the fascinating story of Roger Maris:

When I started making a mental list of which players I wanted to include on the “Nine Innings” album, I quickly thought of Roger Maris and immediately knew I would write a song about him.

Roger Maris and I both grew up in Fargo, North Dakota, and reminders that Roger called the place home are scattered all over the city. One of these Maris landmarks is the Roger Maris Museum, which can be found in the Roger Maris Wing of West Acres, the local shopping mall in Fargo.

When I was young, there was this commercial — maybe for a jewelry store? I cannot remember — that aired repeatedly in town, and it ended with a somewhat nasally voice letting you know the location of the store by saying, “Roger Maris Wing, West Acres.”

So, when I originally wanted to write a song about Maris, it was not because I thought his would be a rich story to tell — though it is. I just wanted to amuse myself by including the words “wing” and “West Acres” in the song — and not just anywhere, but in the very last line, as they had been used in the commercial.

As a result, the lyrics were hard to put my finger on at first. Wanting to add a little inside joke to the lyrics is nice, but it is not enough to build a song around.

In searching for the words, I found the song becoming more and more personal. At the time, I was feeling lost in a deep depression, struggling to get my head above water. And so, it was from that place that I connected to Roger Maris in this song.

Maris hit 61 home runs in 1961, breaking Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record. And it almost killed him. Instead of a celebrated, joyful chase, his hair started falling out in clumps. He was isolated and ostracized, and in many ways the experience seemed to change him forever.

“Every day I went to the ballpark — in Yankee Stadium as well as on the road — people were on my back,” Maris said. “The last six years in the American League were mental hell for me. I was drained of all my desire to play baseball.”

Maris had worked for most of his life to become a good baseball player, and in 1961, after a few really excellent seasons, things came together in ways no one had seen coming. In some ways, he had gotten better than he had ever intended.

And his reward for happening to become exceptional? To be told that he should be somebody else. To play in front of too many who saw him only as not a legend, as not immortal, as not The Babe or The Mick or the Yankee Clipper.

“I never wanted all this hoopla,” Maris said. “All I wanted was to be a good ballplayer and hit twenty-five or thirty homers, drive in a hundred runs, hit .280 and help my club win pennants. I just wanted to be one of the guys, an average player having a good season.”

If anyone was to inherit Ruth’s mantle of royalty, passed on through Gehrig and DiMaggio, it was supposed to be Mickey. Mickey Mantle was Mickey Mantle! Maris was just a guy named Roger who grew up in Fargo, a good working-class complement to the anointed Yankee stars.

He was a sidekick, even if a great one, and hallowed individual records aren’t handed out to sidekicks. Maris, to many, didn’t deserve his own accomplishments — didn’t deserve to be himself, out there doing his best.

“I don't want to be Babe Ruth,” Maris said. “He was a great ballplayer. I'm not trying to replace him. The record is there and damn right I want to break it, but that isn't replacing Babe Ruth.”

It ran so deep that even after Maris had broken Ruth’s record, the powers that be tried to mark Roger’s name with an asterisk. Technically, see, Maris had hit his 61 homers in the modern 162-game season, they said, while Ruth had hit 60 in a 154-game campaign — the standard length at the time.

At some point during that 1961 season, I imagine Maris must have reached a moment of truth. I picture him looking himself in the mirror and realizing that this record was in his grasp. He had put himself in a position to achieve something great, and like hell if the world’s expectations were going to keep him from that.

Who do I want to be? Who am I? How do I want to live? What’s important to me? Why am I so pale? So thin? Why does this stretch of brilliance feel like a time of trial? Why have I withered to this extent, and has anything in this situation been nourishing me?

There comes a time when we have to decide to live according to what we believe is right, or to give in and wither away from the inside. The only way to rise from these darkest moments is to realize that we are more than any one role or identity, more than any one skill or any single mistake — that our inherent value endures through all changes and all times.

In fully accepting that he was more than just a baseball player — reconnecting with his soul, his family, his roots — I imagine Roger transforming his anguish into resolve. You don’t think I’m good enough to break this record? Just watch me do it. Just try to stop me.

“Maybe I'm not a great man,” Maris said, “but I damn well want to break the record.”

And finally, during the last game of the season, he did it. He deposited yet another pitch over the right field wall, and in spite of everything, he — Roger Maris — had done something incredible. Sixty-one home runs.

I picture him carrying out his magical mission with clarity at the end, breaking an immortal record as a man who knew he wasn’t bound himself for immortality in the Big Apple. He would return, in a sense, to his humble beginnings as a good man from North Dakota.

In the end, “Roger Maris” is a song about rising above darkness, about not carrying the burden of other people’s expectations, and living instead in our full brilliance. We can be of no greater service to the world than when our light shines its brightest.

“Roger Maris” features Kenneth Maldonado on drums, Andre Calderon on bass, Louie Opatz on guitar, Jon Halvorson on backing vocals, and Barry Cooper on horns. Recorded, produced, mixed and mastered by Jeff Woollen at Raven Cries Recording Studio.

The beautiful album artwork was drawn by Fargo artist Zach Scheet, my childhood friend, next-door neighbor and frequent Wiffle ball opponent.