One obvious advantage to living in New York City is how spoiled we are musically. Every major musical act plays shows here, small acts you might not get the chance to see elsewhere, week long residencies, combinations of musicians you won’t ever see play together again. The sheer amount of great music any given night is staggering. You can’t be everywhere at once and it’s inevitable that you hear about something the next day that you kick yourself for missing. I was fortunate enough to catch Kenny Endo on Taiko and Hiromitsu Agatsuma on Shamisen (basically a Japanese musical pairing equivalent to seeing Eric Clapton and John Bonham*) as they performed a show, together for the first time, in a small intimate venue, the Japan Society auditorium, right across the street from the UN. The instruments they play may be unfamiliar to most Westerners but anyone who enjoys seeing mind-blowing virtuosity would have appreciated this show.

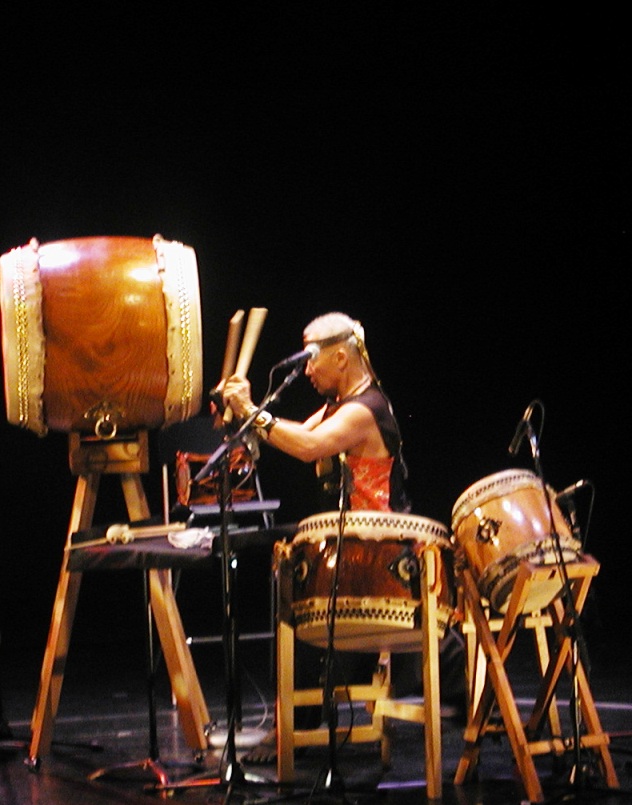

Endo, one of the world’s leading taiko artists (taiko is a Japanese word that generically refers to percussive instruments performed with hands or sticks) opened the performance with four solo pieces, one traditional and three of his own compositions. The pieces were captivating and aggressively nuanced, varying from what seemed to my uneducated ears as highly traditional to extremely modern and complex. Interestingly enough, considering his mastery of the instrument and the difficulty of permeating Japan’s notoriously rigid culture, Endo does not come from a traditional Japanese background. Born in California to Japanese parents, he began playing t he drums at age 9, taking on the taiko when he was 22 after seeing an ensemble in Los Angeles. A jazz drummer at the time, he eventually needed to make a choice between being a working jazz drummer and immersing himself in mastering the taiko if he wanted to continue down that path. He made the decision to move to Japan and study taiko, a one year plan decision that turned into ten. This ten year immersion provided him with a level of mastery that earned him a unique honor, being awarded a natori (stage name) in hogaku hayashi, Japanese classical drumming, the only foreigner ever to receive this honor.

he drums at age 9, taking on the taiko when he was 22 after seeing an ensemble in Los Angeles. A jazz drummer at the time, he eventually needed to make a choice between being a working jazz drummer and immersing himself in mastering the taiko if he wanted to continue down that path. He made the decision to move to Japan and study taiko, a one year plan decision that turned into ten. This ten year immersion provided him with a level of mastery that earned him a unique honor, being awarded a natori (stage name) in hogaku hayashi, Japanese classical drumming, the only foreigner ever to receive this honor.

His ability to interweave this skill at the traditional taiko style of playing with his facility for jazz drumming has enabled him to create an incredibly dynamic style of performing that captivated the audience and was literally breathtaking. It comes as no surprise to read in his bio that he’s performed with Michael Jackson, Prince and opened for the Who. This was world class musicianship at its finest. At one point, before they began their joint performance, the two musicians were interviewed on stage. Endo was asked about coming to Japan and attempting to master taiko as a foreigner, both in a musical and cultural sense. While freely admitting that this was no easy task, his comment that “the love of music transcends all borders” struck me as being particularly appropriate for the occasion.

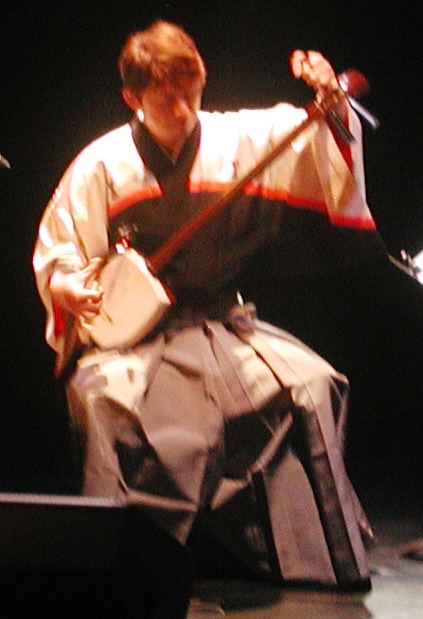

His counterpart on shamisen, Hiromitsu Agatsuma, was an equally brilliant performer. Shamisen, a three-stringed banjo-type instrument, is another extremely important instrument in traditional Japanese music. The style of shamisen performing that Agatsuma has mastered is called tsugaru-shamisen, which originated in the far north of Japan. A cold and rural part of Japan, this passionate, rhythmic and more improvisation friendly style of shamisen evolved from poor farmers exiled from their homes for being physically unable to work and forced to earn their living as wandering shamisen players. (Anything about this remind you about another form of music, more familiar to us here in the US?) Agatsuma grew up in Japan taking up the shamisen at six and winning first prize in the national competition for tsugaru-shamisen at 14. Similarly to Endo, Shamisen chose to master the traditional form and aspects of the instrument and style of playing before taking this expertise and beginning to experiment with it, combining aspects of other types of music that held his interest. Asked about the renewed popularity of the shamisen as an instrument for young people to learn in Japan, he said that when young shamisen students tell him they want to avoid the time-consuming difficulty of truly mastering the instrument in every historical aspect of its form, he tells them “you can’t break tradition until you’ve learned it”. His three piece solo set included both traditional tsugaru-shamisen folk songs as well as his own, more modern-sounding compositions and his performing was fiery and percussive with torrential, Steve Vai style licks, “speed shamisen”, if you will.

in Japan, he said that when young shamisen students tell him they want to avoid the time-consuming difficulty of truly mastering the instrument in every historical aspect of its form, he tells them “you can’t break tradition until you’ve learned it”. His three piece solo set included both traditional tsugaru-shamisen folk songs as well as his own, more modern-sounding compositions and his performing was fiery and percussive with torrential, Steve Vai style licks, “speed shamisen”, if you will.

Both performers were brilliant in their solo sets but when they combined for three songs in the final set (the first time ever doing so), the show went to another level. They performed one Traditional Japanese song and one each of their own compositions and even though there was an element of the dueling solos (not a bad thing!), I was most impressed by the way they fed off each other while playing together. Seeing two of the best musicians in the world at their instruments is always a very special experience and it was made even more so for feeling truly fortunate to be present at a show even most music savvy New Yorkers were not aware of. Check out the Japan Society, they have a lot of cool cultural programming year round, and you would not want to miss an opportunity like this again.

*comparison meant to illustrate the virtuosity of the performers and the unique rarity of seeing them perform together (obviously John Bonham would need to still be alive).