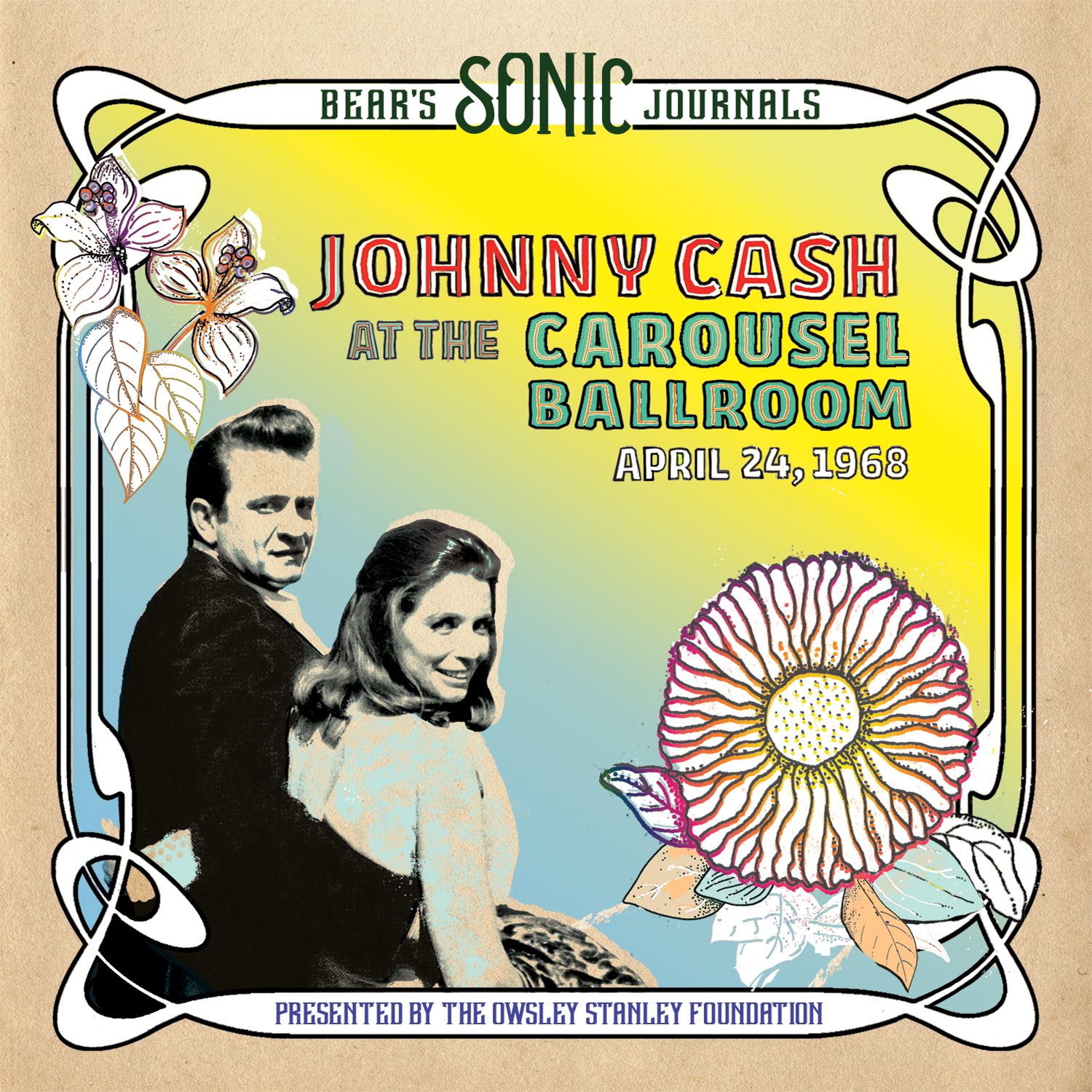

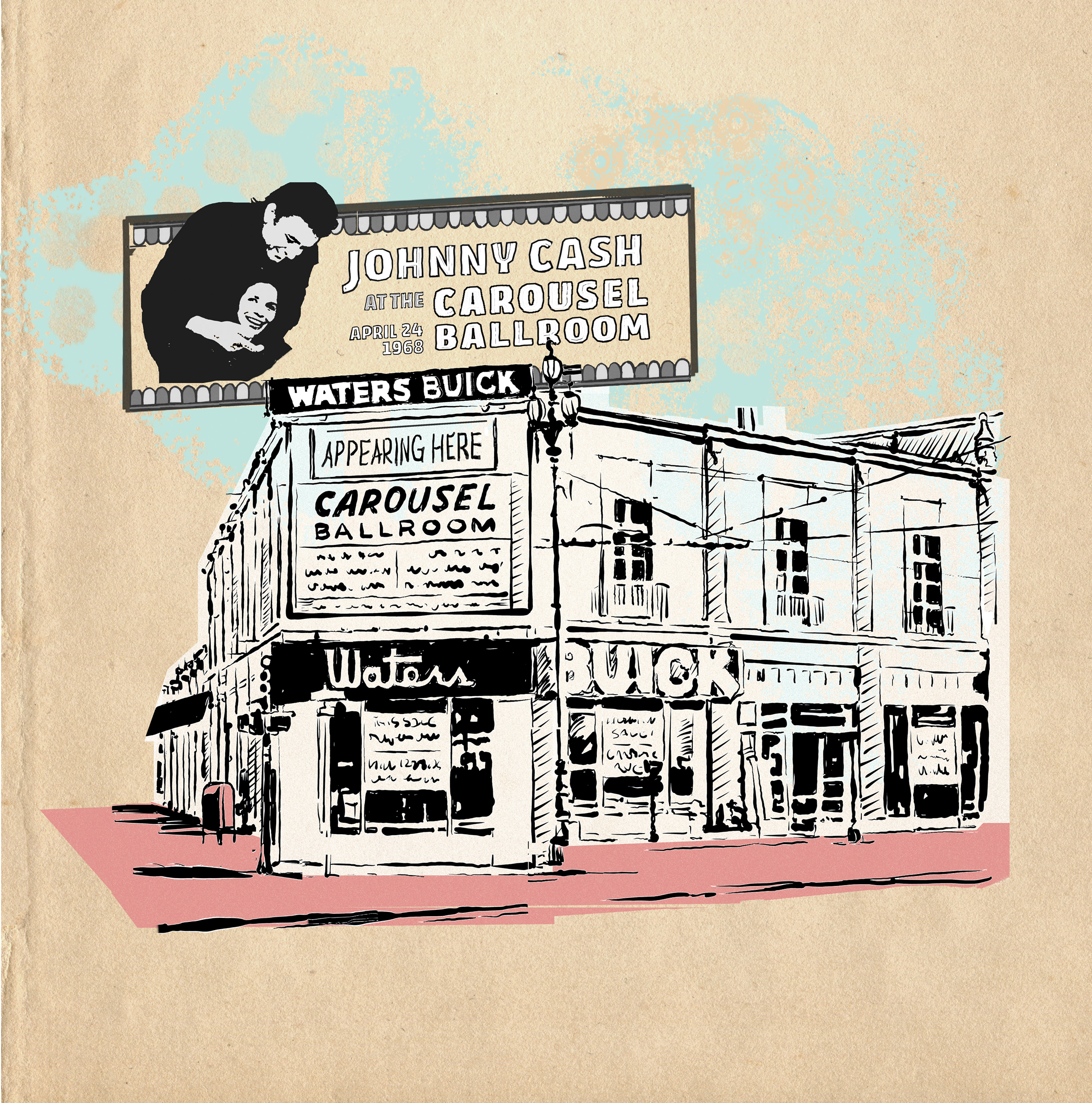

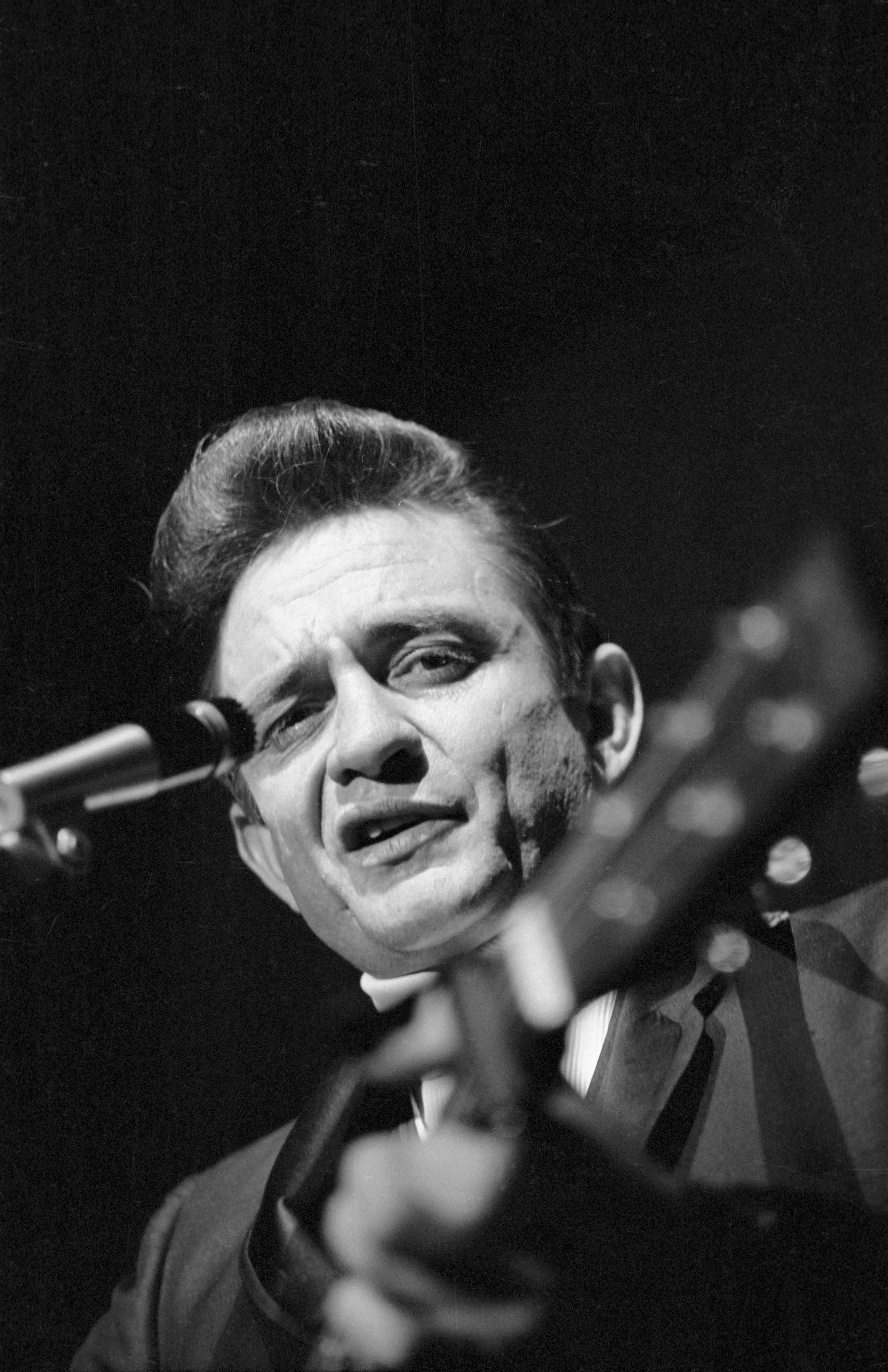

Sometimes from within the musical world the cosmos comes together in just such a way, at just such a time that it produces something truly special. In this case, two historic characters, Johnny Cash and Owsley “Bear” Stanley collide with Haight-Ashbury’s famously historic venue, The Carousel, in one of the most historic times in music history, 1968. With the Johnny Cash, Live at The Carousel April, 24th 1968 release from The Owsley Stanley Foundation’s Bear’s Sonic Journals collection, we are not only introduced to Johnny Cash in a completely different light but also taken into the extraordinary mind and innovation of Owsley Stanley.

In the words of Dennis McNally, longtime publicist of the Grateful Dead and author of, A Long Strange Trip, “The Johnny Cash show is a fascinating show. It was being run by an unconventional group of people at the Carousel. (The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, and Big Brother and the Holding Company.) Ron Rakow, (manager of the Grateful Dead at the time) made a last second offer inviting Johnny Cash to come to the Carousel, creating an add-on to the end of Johnny’s American tour for a completely different market, mainly a bunch of hippies on a Wednesday night in San Francisco. And the result," Dennis adds, “Was that Cash felt it wasn’t a regular show so he could be a little more loose and bring in songs he wouldn’t ordinarily, songs that he was not doing as a regular part of his set, like a couple of Dylan songs, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right, and one of the earliest known live recordings of “One Too Many Mornings”. I don’t think he played a "Ballad of Ira Hayes” as a regular thing, but he did that night. So you get this document of his musical life. And of course his regular material is in there too, but you get a certain portrait of him that’s not his conventional regular show.”

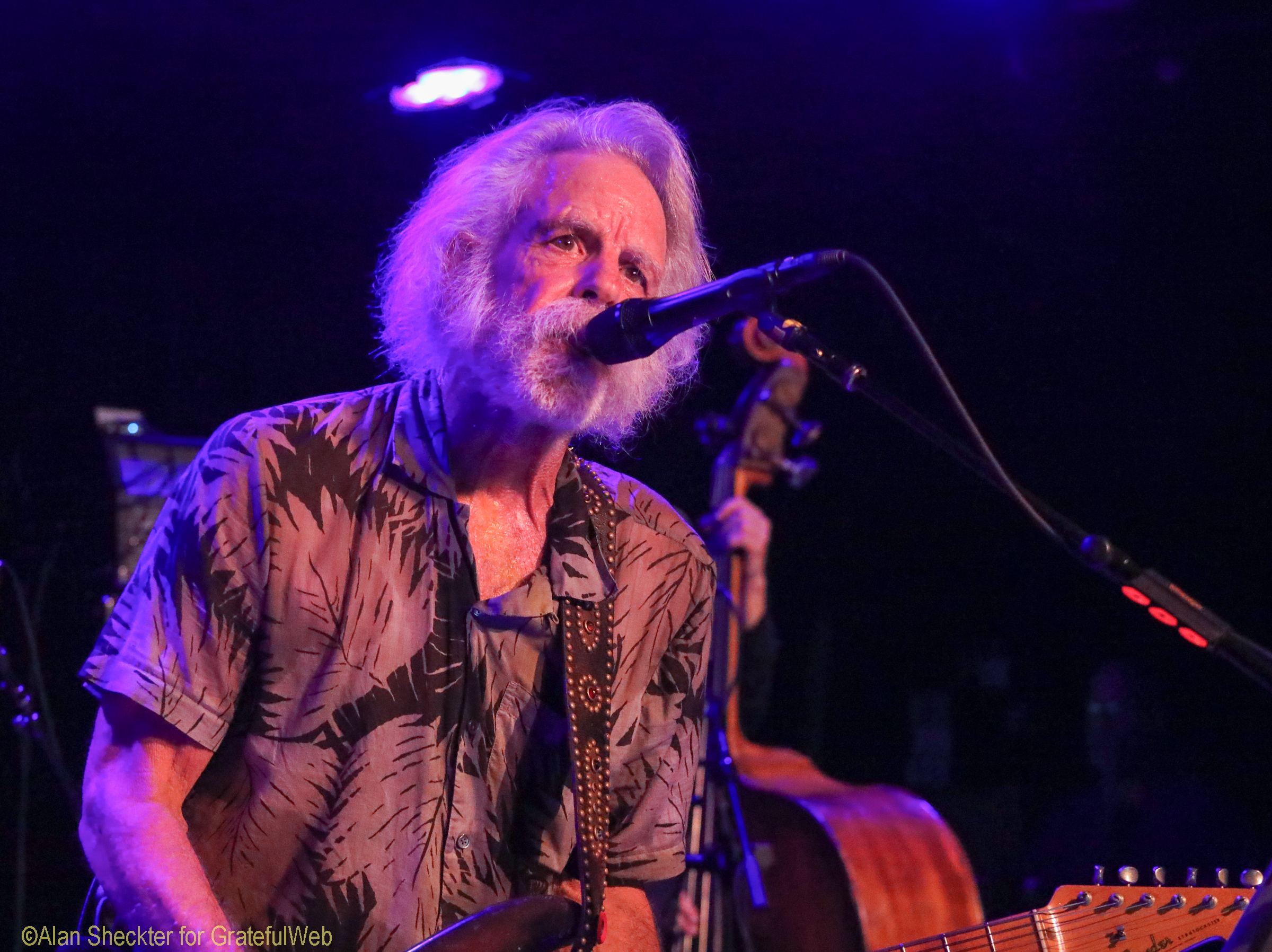

And while Johnny is famously known for his country flair, we cannot underestimate Johnny Cash’s influence on psychedelic music, or music in general, as is made evident in the personal writings included with the Cash release. As Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir states in one, “Every artist of any stripe is first and foremost a storyteller. Johnny Cash is more than exceptional in that regard, taking on the personalities and traits of the characters that he’s portraying. As he sings the lines of his various characters, you can hear the subtle differences in the way he intones his words, depending on who he’s representing, which tells me that he’s completely given himself over to the character. That’s something I learned second-hand by listening to him. The Johnny Cash who is famous, whose record you bought, is just a bystander. He’s not the focus; instead, that character is really the one speaking.”

Hawk Semins, a OSF board member, the foundation’s lawyer, and executive producer was happy to offer us an inside glimpse with his enclosed liner note writing. “The first thing we saw when we entered the control room at the Cash Cabin Studio was the Alembic bass on the wall, the sister to Dave Schools’ Cashwood. Can you imagine a better icebreaker for ambassadors from second-generation psychedelia arriving to meet with second-generation country royalty? The connection between Owsley and Alembic is the stuff of legend in the Bay Area music scene – it’s where the sonic magic took place, the laboratory where base metals were transmuted into gold – it’s where some of Jerry Garcia’s iconic guitars and several of Phil Lesh’s basses were made; it’s also where Owsley once kept his legendary archive of tapes. But walking into the Cash Cabin, the connection between Alembic and Johnny Cash seemed as improbable to us as perhaps others might have imagined Johnny and June playing country music in a psychedelic ballroom in San Francisco in 1968. And yet that’s exactly what we came to discuss – this long-lost, magical night when Johnny and June met the hippies.”

Sound is the extraordinary cosmic fingerprint of each thing and is one of the foundational phenomenons of life itself. Amazing in its depth of meaning, we’ve all had song move and open us in deep and profound ways. Clashing, we may repel and call it noise. Yet when all things come together in harmony, like notes of a glorious chord, such as Johnny Cash, Live at the Carousel, we open ourselves and give into the sublime. Music is a spaceship into the cosmos of experiential being for both the artist and the listener, and within each vibration lies the power to move us, to make us feel, to connect our emotional being with the great all, reminding us that life itself is a vibration. Plunging us ever deeper into understanding, music opens us to the magnificent and infinite gateway of sensation. And yet, often times in losing ourselves to the sound itself, we forget to recognize the delivery. In the words of Robert Hunter, “The storyteller makes no choice. Soon you will not hear his voice. His job is to shed light and not to master.” Sound is a universe to be explored, in its creation and its ramifications, and nobody knew this better than Owsley Stanley.

In the words of the Owsley Stanley Foundation, “Owsley used a simple and clean approach, one based on solid scientific principal. He never used equalization (electronic tone control) on individual microphones or on the PA output to correct a poor sound, feeling that such manipulations improperly altered the sound created by the musicians. Instead, if the sound in the hall wasn’t just “right,” he repositioned the microphone or replaced it with a different type of mic until the sound met his standard. As a result, his live sounds were clean, clear, and pure, not electronically corrected. He viewed his role as precisely facilitating the transmission of the music to the audience without altering or manipulating the sound —his goal was to give the musicians complete control over what the audience heard.” If you’d like, you can read more on this here: https://owsleystanleyfoundation.org/about-owsley/

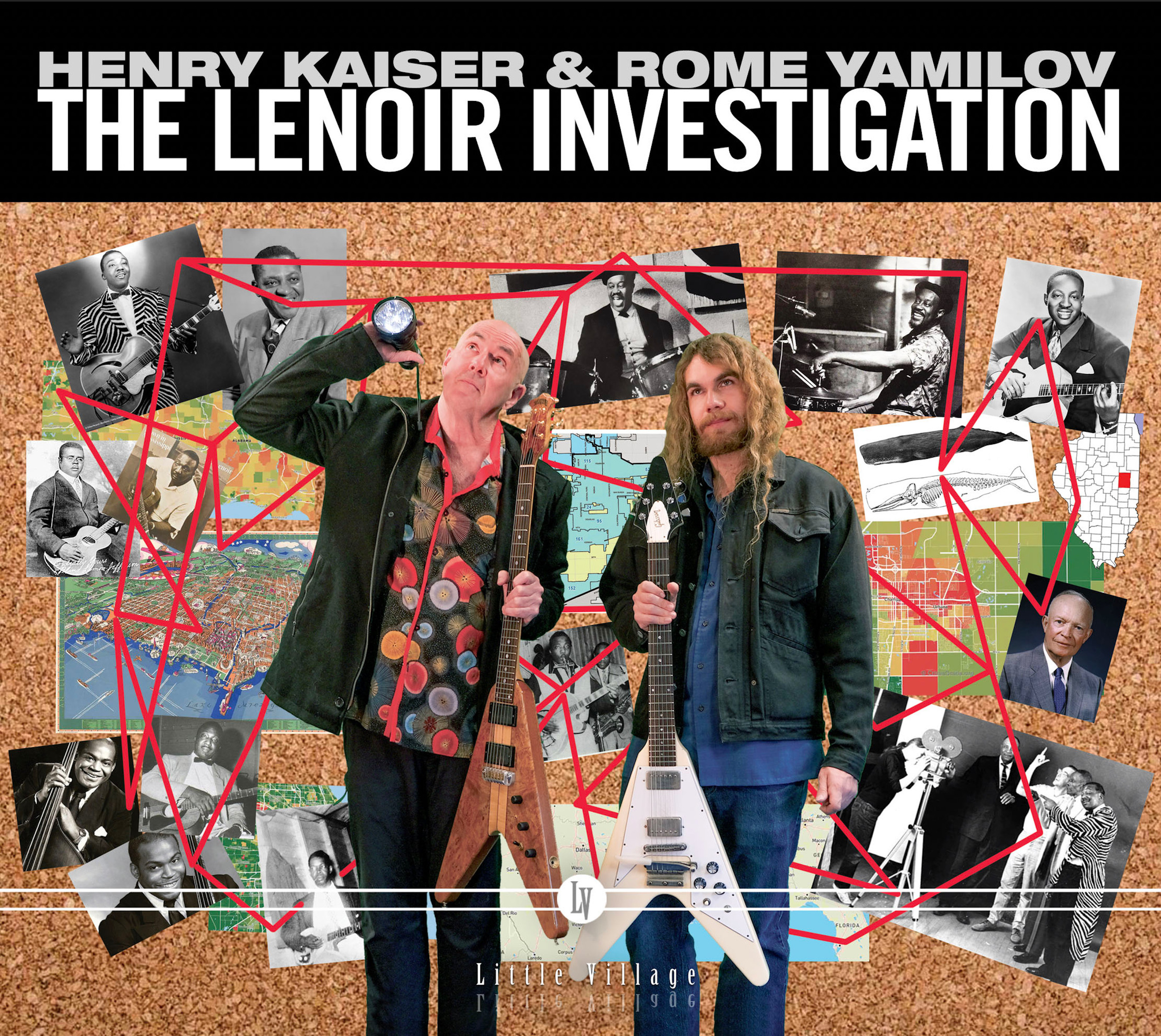

Blair Jackson, author of, Garcia: An American Life, goes on to tell me, “Bear was the guy almost totally responsible for live sound systems being based on other really good systems other than just being two speakers for output. He’s the one who, in his very first systems for the Grateful Dead went and got really hi-fi equipment, hi-fi speakers, and figured out ways to deliver music through that. There was no sound system before the late sixties/early seventies.

“He’s also one of the people who started using monitor speakers because people before that couldn’t hear what they were singing. The music was coming out of giant speakers that were on either side of the stage, not directed in the right way. It’s hard to really quantify how much he did but he did a lot. Almost everyone gives him a lot of credit for a lot. They appreciate his insistence on quality. It was so much part of his makeup.”

Blair continues, “Just as LSD influenced the way the Grateful Dead played, it influenced the way Owsley wanted the band to sound, you know, out front, so they sort of had each other, of them being able to hear the way most bands couldn’t on stage because of his innovations and the things that he wanted every player to be able to hear through monitors or whatever so they were able to become more sophisticated and to develop their sound in a stronger way by being able to hear each other well.

“Owsley never really lost that fire for that sound. He is the eccentric, that’s for sure. Everyone has a great Owsley story. That’s what so much of the lore of Owsley is about.”

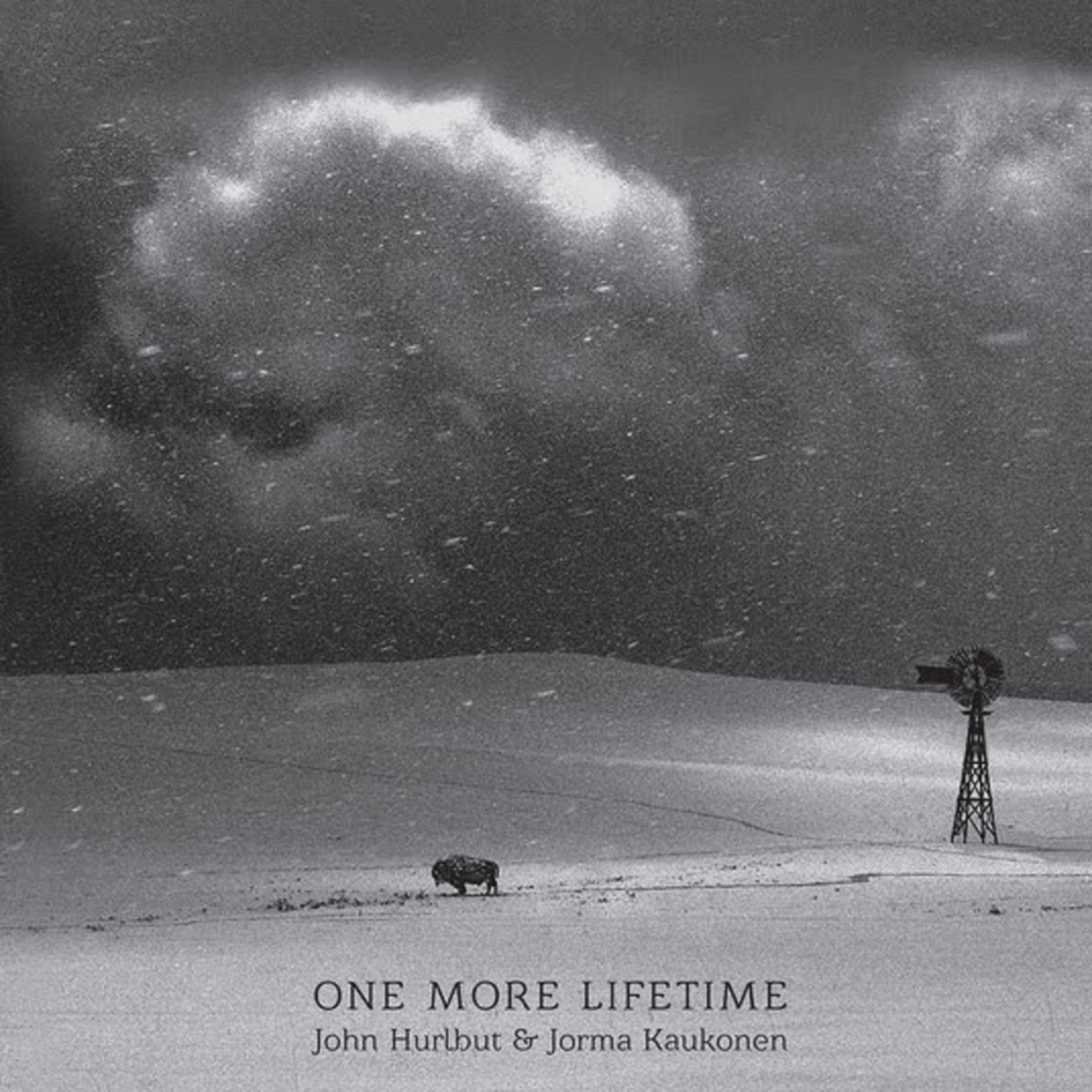

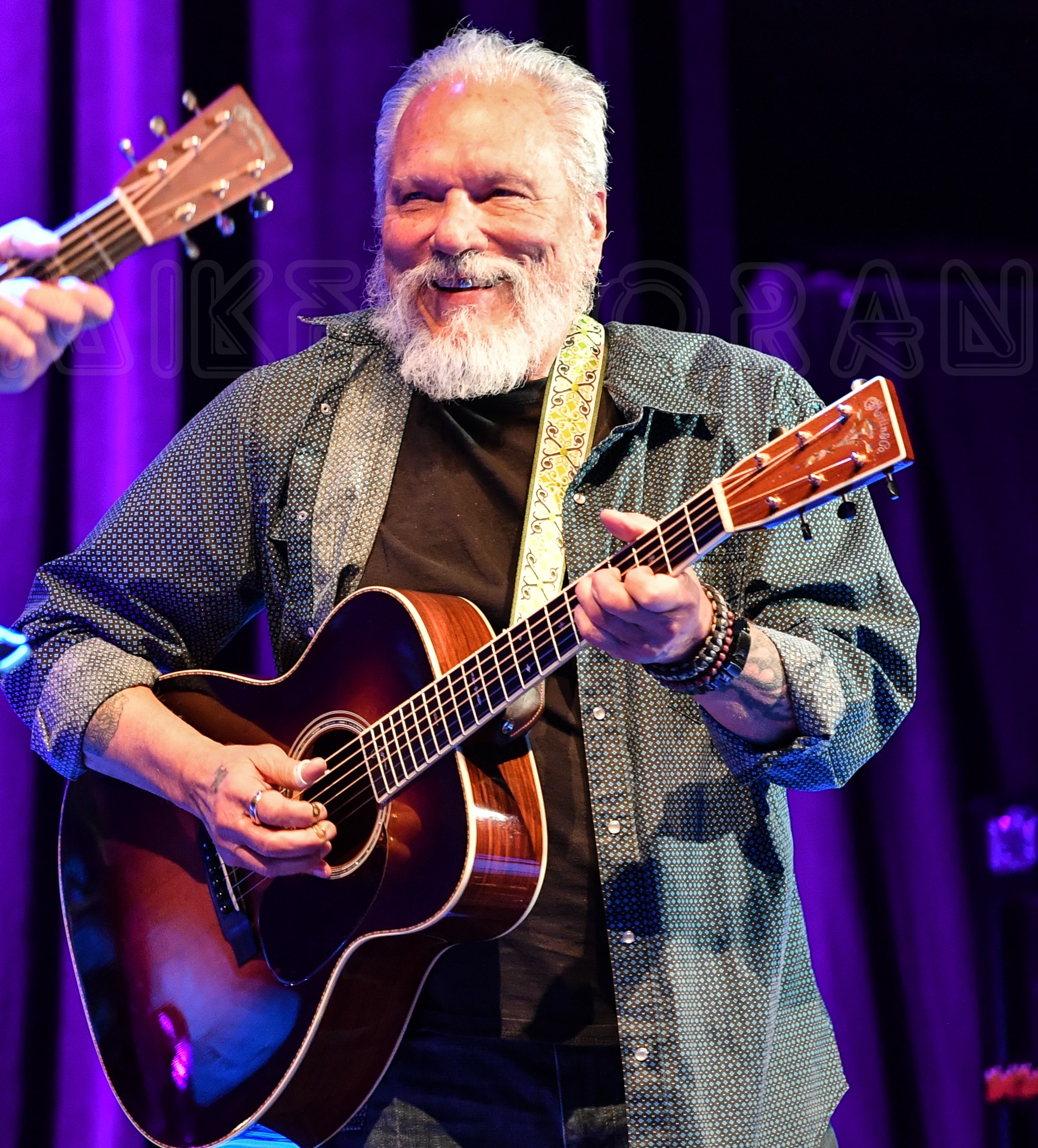

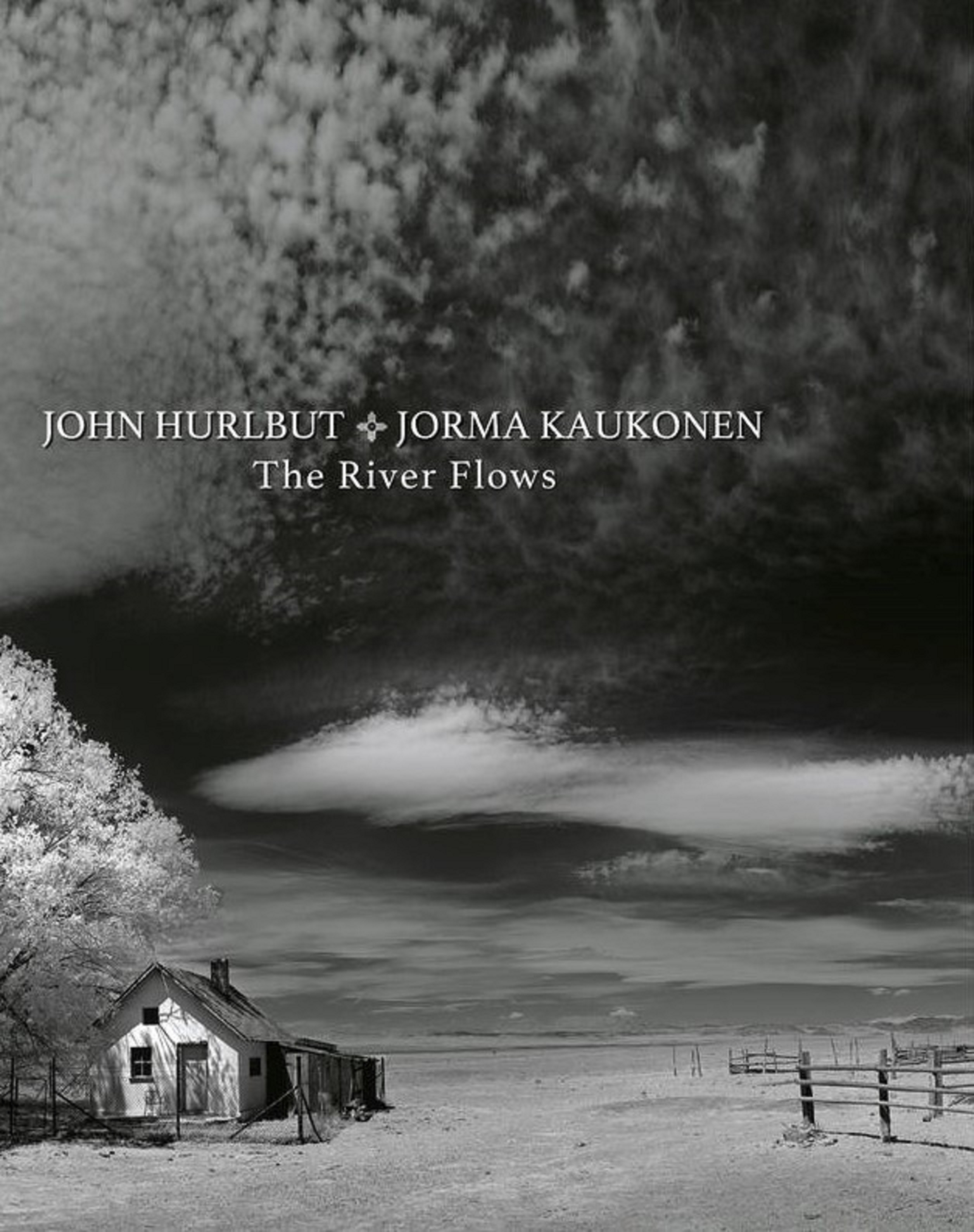

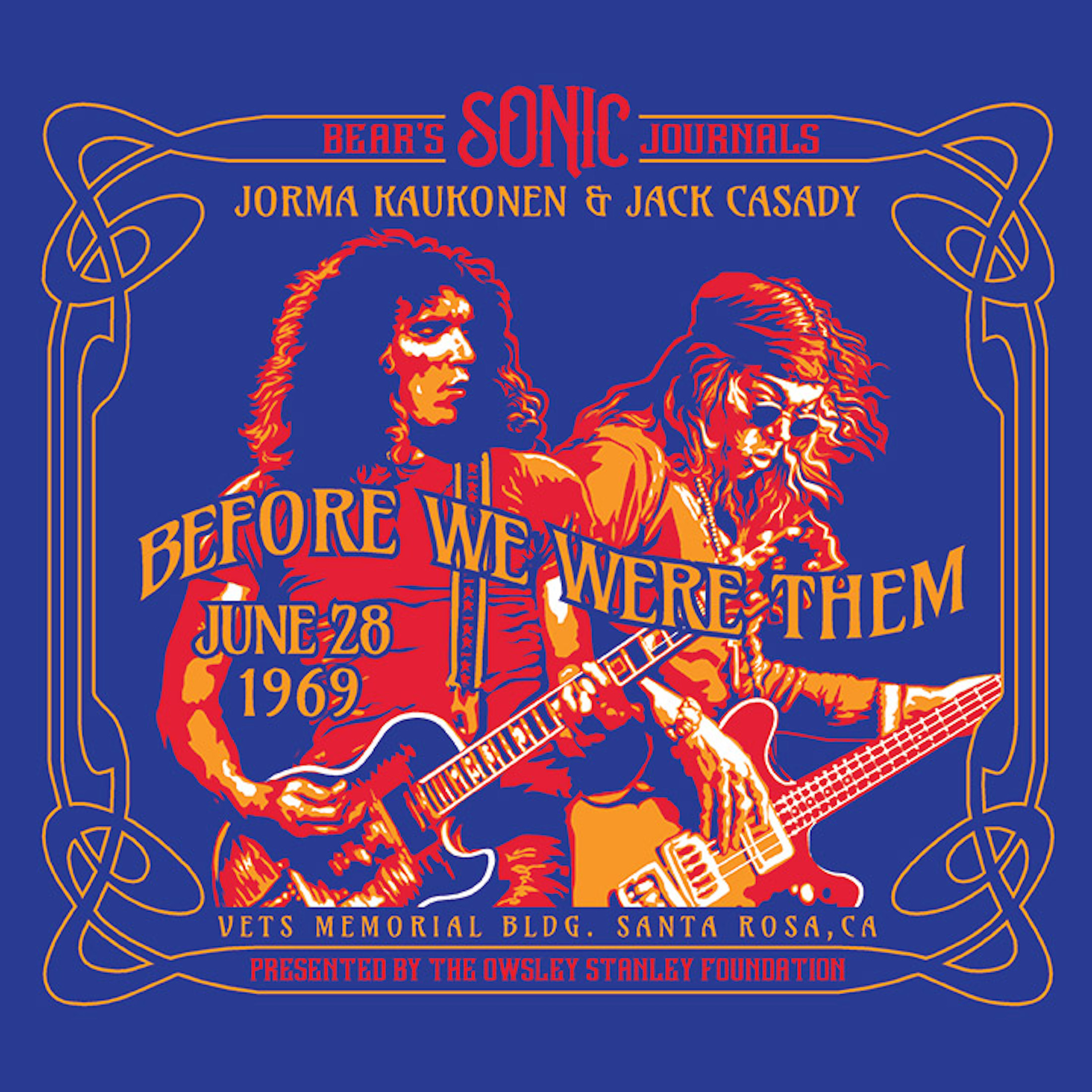

Owsley “Bear” Stanley was indeed a pioneer of sound, as well as an explorer of vibration, and most definitely a character extraordinaire. He is certainly not a man that can be defined by something as limited as word. He was a being that had to be experienced to be truly appreciated. And while we easily recognize the people who make up the band, we often overlook the sound man within the sound. As Jorma Kaukonen recently told me (a product of a Bear’s Sonic Journals release himself), “The sound man is as important to my show as I am because he gets the sound from me to the audience. It’s the sound man that brings the sound to the listener.” In this light, it’s easy to see the sound board is an instrument in itself, just as the design of the sound system is itself an art form. Owsley’s electronic inventiveness and creative curiosity, along with his drive to perfection, was dead-set on the preservation of sound in its truest form. A master of delivery, Owsley Stanley didn’t just bring the sound to the audience, he brought the audience to the sound.

And like Owsley, Johnny Cash was an explorer in his own right, and no easier of a man to define. And while I must admit, when I first began to listen to the show, my immediate knee-jerk response was that I liked the energy of the Folsom show better. Yet, as each song began to float by, I felt something pulling at me. I stopped in my writing and listened closer—Bear is certainly adding something that can’t go unnoticed. Like an invisible member shining forth, I sense a different light is being cast . . . and suddenly, Cash took on new meaning. What was it? Recalling the words of Owsley’s son, Starfinder, president of the Owsley Stanley Foundation, I hear his voice pop into my head. “When you’re listening to this, you should put your speakers together, because then, the main sound images, which is the instruments that are being played, is coming at you simultaneously from the middle, which in effect is the way you hear it at a show. It makes you feel as if you’re standing on stage.”

Heeding his words, I move my speakers next to one another and sit on my couch before them. Closing my eyes, I allow the music to overtake me and instantly realize, “Yes!" This was it. The sound wasn’t coming at me. I was in the midst of it all. I was on stage with Johnny Cash! I was within the voice, the music, the song. And hence, his relaxed, genuine demeanor shines through, almost as if he were my friend just sitting back and playing in my living room. Owsley had captured more than the music. He had captured the man.

Later, Blair Jackson defines the experience to me. “The specifics of the Cash show at the Carousel is interesting from a sonic perspective because Owsley chose to put the listener in the middle of the band on stage. It just takes a little getting used to, at least it took me a little to get used to, to adjust my thinking, to see where I am as a listener in the mix. So it’s an unusual approach, but I think it pays off. There’s a real clarity to it, and there’s also a way that you sort of enter into the music in a different sort of way because it’s not coming at you, you’re in it. So that’s what he’s going for and I think he achieved that. And once you get used to it, I think it’s pretty exciting.”

Talking over my experience with Dennis McNally, he tells me, “The Grateful Dead and their sound engineers made considerable efforts to improve the listening experience of concertgoers. Their crusade began with Owsley. They used a wave measuring device, which was actually invented to test the harmonic strength of metals, and this would measure the room, and you discover which frequencies would resonate too much, others too little. And so the idea would be to tune the room flat. So you would start from there with equalizing the sound system to make it sound perfect to the audience. The goal was that the equipment for amplification should not cause any distortion to the music. The effect that Owsley was trying to do was recreate an aural portrait of the way it was on stage because he’s doing this live recording. Within the limits of the technology at the time, he comes up with an absolutely masterful aural portrait.”

Speaking of Owsley, Blair Jackson explains, “The Grateful Dead were a band of firsts. I mean very early on, they got a reputation for having the best sound of any band that was out there touring. A lot of the other sound engineers copied what they were doing or talked to them about what they were doing and how they were able to isolate instruments and how they were able to combine instruments in interesting ways in the PA and give a faithful reproduction of what was actually being played.”

And while I found the quality of sound uniquely submersive, and enchanting, I still felt there was more. Perhaps it was Johnny himself. I couldn’t help but think that the moment reflects what we each bring to it. In the words of Johnny Cash’s son, John Carter Cash, “On the 24th, he (Cash) traveled to San Francisco and performed a somewhat unconventional show. With a smaller version of his band, only my mother, W.S., Marshall, and Luther in support, Dad gave what I believe to be one of the most intimate and connected shows I have ever heard. When I listen to this masterpiece recording now, I am drawn into his life at the time. I recall the struggle and pain he endured. In his voice, I hear enthusiasm, the undeniable adoration for his audience, his delight in the music.”

As many of us may know, to rise up out of the ashes and be born anew can be quite euphoric in its own right, primarily due to the traumas endured in getting there. John Carter Cash so graciously exposes his father’s struggles leading up to the Carousel show in his liner note writing by sharing an intimate story. “He owned a parcel of land near Nickajack Lake, not far from Chattanooga. On that property was a cave. He would often wander its chilly and seemingly endless corridors, far out of sunlight’s reach. There, the world outside and the passage of night and day faded from reality. One day, in desperation, he sought to give up on life. Upon entering the cave, he pushed deeper and deeper into the stony earth, losing his way. He left no markings to follow back to the surface. In hopelessness, he smashed his flashlight against a stone. He lay down and passed out. Later, he came to in pitch black darkness. Fear gripped him. For what seemed like hours, he crawled on his hands and knees, seeking the exit. Driven by a sudden clarity and desire to live, he prayed a common prayer of those with but a speck of faith within an abyss of hopelessness: Help me. Give me strength. Get me out of here and I’ll give my life to you, God.”

Later, according to Cash’s son, Johnny Cash wrote to himself on the last day of the year. The letter written at 8:35PM on December 31, 1968 read, “To Myself, I feel that this year, 1968 has been, in many ways, the best year of my 36 years of life...”

With all the excitement about this unearthed release, others choose to offer their insight in special writings included with the album. “I don't think there are any live recordings of Johnny that weren't originally intended to be an album,” says Josh Matas, brand manager of the Johnny Cash Trust. “So to be able to stumble across such a live recording during such a golden era for him, and find that it was recorded in such a dynamic way, is incredible. It's an opportunity to show Johnny in a new light. Knowing that it wasn't originally intended for commercial release, there's something more human and candid about it.”

And Dave Schools of Widespread Panic weighs in on his listening experience with this excerpt from his enclosed writing, “Bear’s recording of Cash’s Carousel Ballroom concert crackles with the energy of the human condition; it is sometimes shaky, sometimes not-quite in tune, but always honestly performed. Cash and his group earnestly render this set of songs with the verve of a man pulling himself out of quicksand and reinventing himself in the moment.”

Not even listed on the official schedule history of Johnny Cash or The Carousel, on this Wednesday night, April 24th, before an intimate crowd of 700, Bear captures a truly honest portrayal of Cash onstage with his then new bride, June Carter, backed by his legendary band the Tennessee Three: guitarist Luther Perkins, bassist Marshall Grant and drummer W.S. Holland. A mere two weeks before the release of Folsom Prison would skyrocket Johnny into historic stardom, Live at the Carousel offers us a never before heard glimpse of Cash at his most genuine self.

“Johnny Cash's brilliance in part is that he connected with everybody,” says Hawk. “That connection came from his ability to invest his own life experience into every word of a song and hold it up as a mirror for all of us to see ourselves.”

And perhaps, most importantly, Starfinder reveals, “This was one of the recordings that he (Owsley Stanley) had put a star next to, and said, 'This is an important journal entry, and this needs to be advanced into the world so people can hear it.'”

The live album, which will be released on CD/2LP, features new essays by Johnny’s and June Carter Cash’s son, John Carter Cash, Owsley Stanley’s son, Starfinder Stanley, the Dead’s Bob Weir, and Widespread Panic’s Dave Schools, as well as new art by Susan Archie, and a reproduction of the original Carousel Ballroom concert poster by Steve Catron. Issued by the Owsley Stanley Foundation and Renew Records/BMG, the release will also be widely available in all digital formats by Legacy Recordings, the catalog division of Sony Music Entertainment.

“Black Muddy River, roll on forever.”

About the Save the Music Foundation:

The Owsley Stanley Foundation is a 501c(3) non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of “Bear’s Sonic Journals,” Owsley’s archive of more than 1,300 live concert soundboard recordings from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, including recordings by Miles Davis, Johnny Cash, The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Fleetwood Mac, Janis Joplin, and more than 80 other artists across nearly every musical idiom.

These analog reel-to-reel recordings are nearing the end of their expected shelf lives and will deteriorate and be lost forever if they are not preserved. Experts believe that the typical lifespan of this media is approximately fifty years if maintained in ideal conditions and have advised the Foundation that the digitization of the earliest of these recordings should occur within the next five years or they will not be salvageable; all of them will continue to degrade and will become unsalvageable unless eventually digitized. The effort to preserve these historically vital recordings is estimated to cost between $300,000 – $400,000 and will require two to four years of studio time by sound engineering professionals to complete. All donations and proceeds from the development of the recordings flow back into the effort to preserve more of Bear’s Sonic Journals and perpetuate Owsley’s legacy, including patronage of the arts in all of its forms. Their staff is entirely comprised of volunteers, and many of the support services necessary to run the organization have been donated by generous contributors that believe in the mission to save this music before it is lost forever.

The Sonic Journals capture vital, unique, and invaluable auditory snapshots from one of the most fertile, influential, and explosively transformative epochs in American musical and cultural history. Not only are these high-quality soundboard recordings the only source of many of these historic live concert performances of now well-known and revered artists, but they also document the development of the innovative approaches to live sound recording pioneered by Owsley Stanley. As such, the Foundation believes that Owsley Stanley’s Sonic Journals are important cultural and historical assets to be preserved for the public benefit, to be appreciated by generations of musicians, fans, historians, ethnomusicologists, sound engineers, and others.

If you’d like to donate to the Save The Music campaign click here. https://owsleystanleyfoundation.org/save-the-music/

Track Listing:

1. Cocaine Blues

2. Long Black Veil

3. Orange Blossom Special

4. I’m Going to Memphis

5. The Ballad of Ira Hayes

6. Rock Island Line

7. Guess Things Happen That Way

8. One Too Many Mornings

9. Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right

10. Give My Love to Rose

11. Green, Green Grass of Home

12. Old Apache Squaw

13. Lorena

14. Forty Shades of Green

15. Bad News

16. Jackson

17. Tall Lover Man

18. June’s Song Introduction

19. Wildwood Flower

20. Foggy Mountain Top

21. This Land Is Your Land

22. Wabash Cannonball

23. Worried Man Blues

24. Long-Legged Guitar Pickin’ Man

25. Ring Of Fire

26. Big River

27. Don’t Take Your Guns to Town

28. I Walk the Line