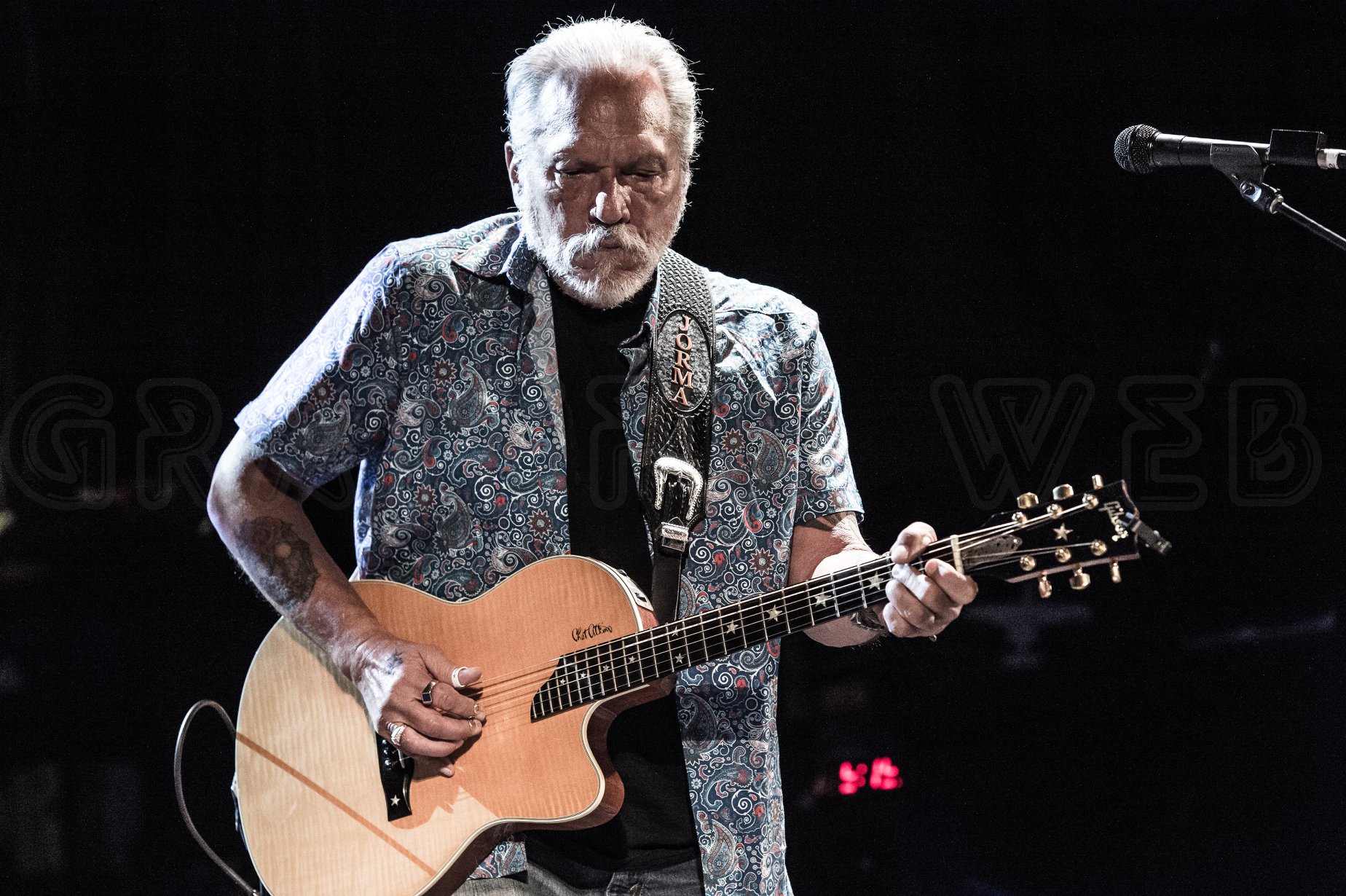

Iconic architects of San Francisco’s celebrated psychedelic sound, Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady, brought their enduring roots-infused mélange, Hot Tuna, to Eugene’s (Ore.) McDonald Theater on Sept. 1st and suitably verified their vaunted rock-and-roll credentials. Though not as widely known as their seminal 60’s group Jefferson Airplane, Hot Tuna have been playing searing, head-spinning shows for nearly five decades. Their recent Eugene performance, thick with fan favorites, was a spirited affirmation of their imperishable creative potency. A masterful demonstration of highly refined technique rippling with emotional intensity, Hot Tuna’s Eugene appearance impressively celebrated their rich, musical history and forcefully asserted their ongoing significance.

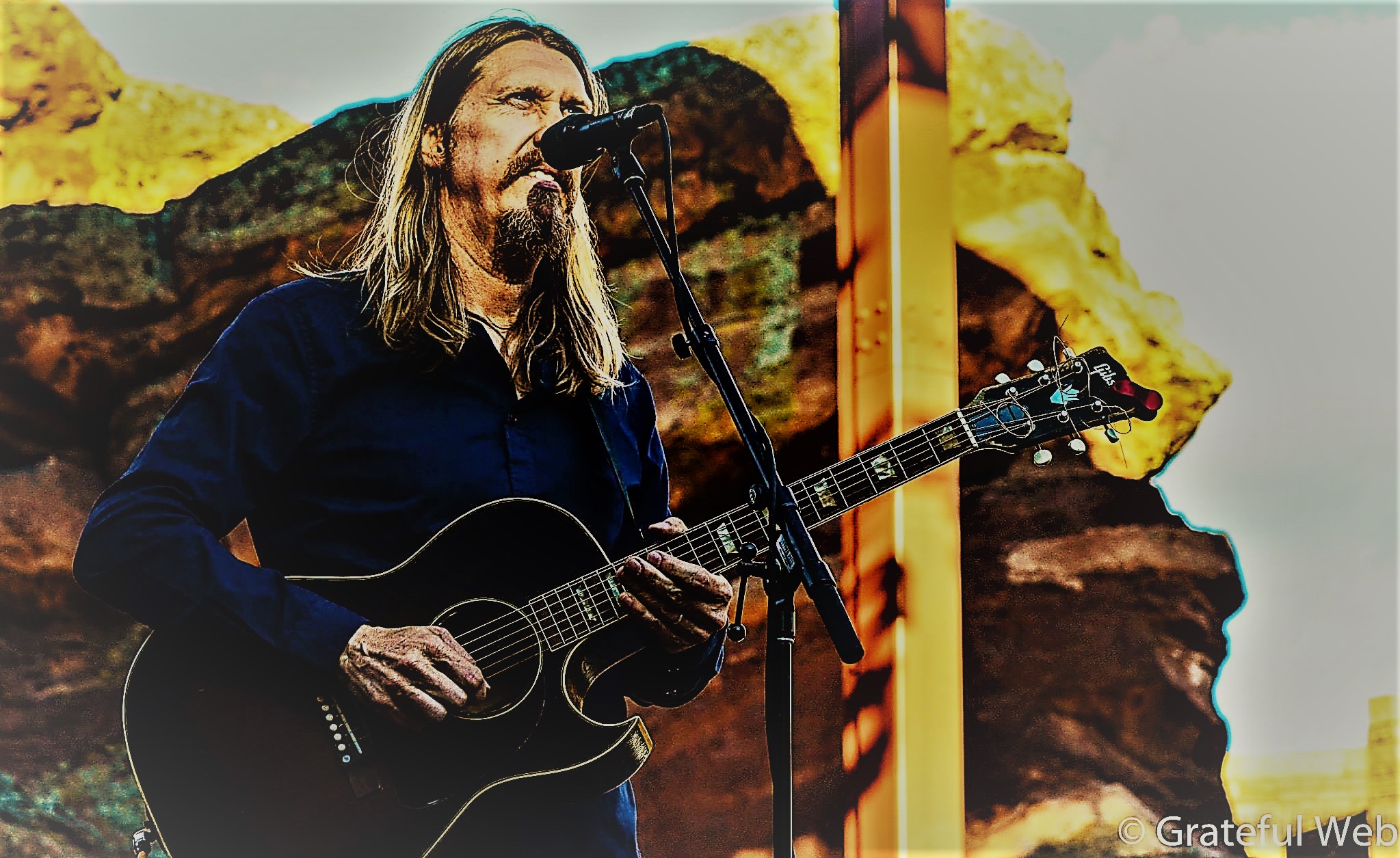

A skin-tingling response swept through the crowd as these two legitimate rock stars, veterans of Monterey Pop, Woodstock and Altamont, slid onto the bare stage, unadorned by any pretense. Music is always the focal point at a Hot Tuna show. There are very few theatrics. They simply aren’t necessary. Kaukonen on guitar, Casady on bass, and in this case, the very capable Justin Guip on drums, are riveting entertainment by themselves.

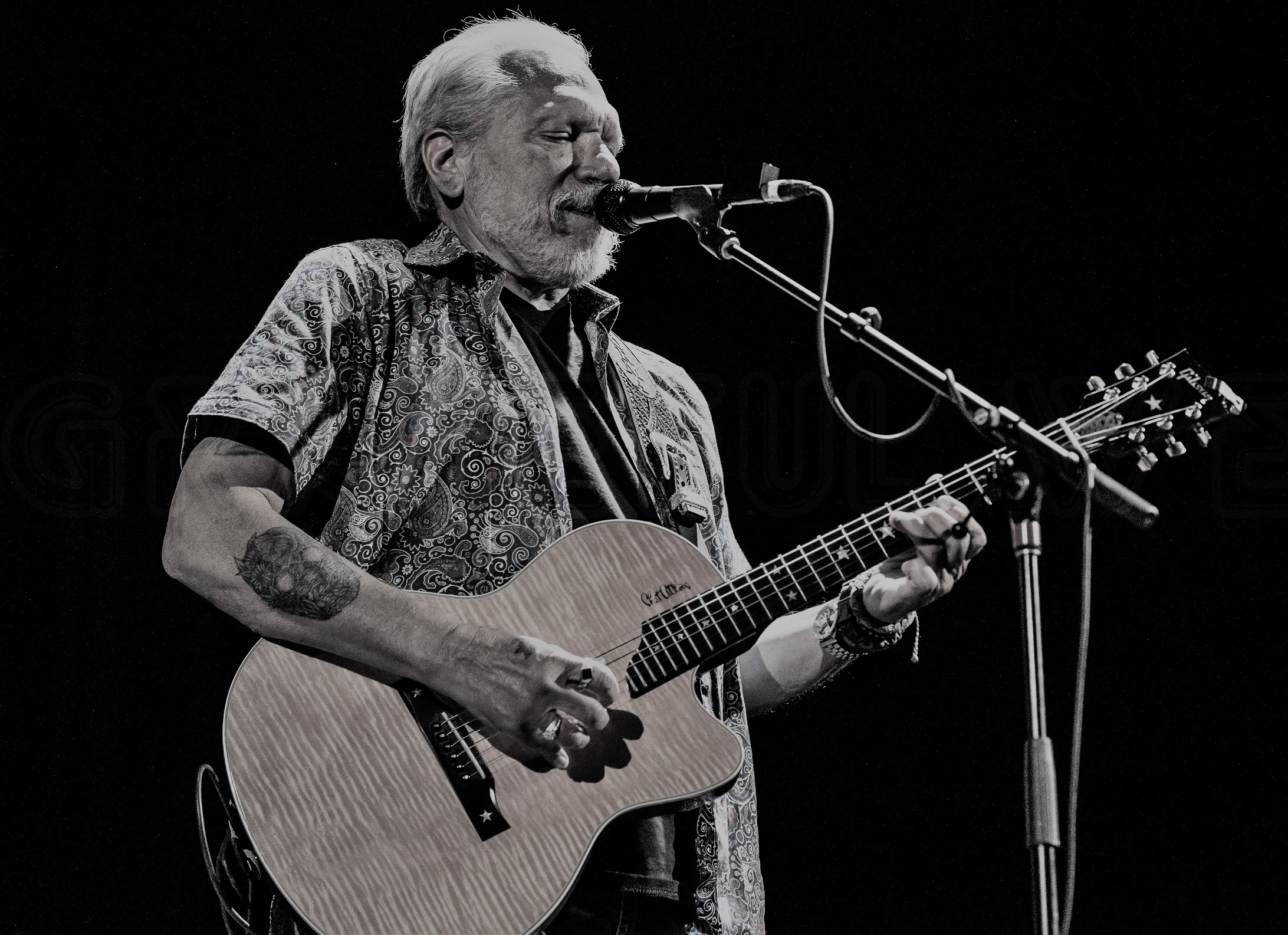

They opened with the classic Kaukonen original, “Been So Long,” a seething rocker from Hot Tuna’s 1971 live album, First Pull Up, then Pull Down. It’s also the title of Kaukonen’s recently published autobiography, Been So Long, My Life and Music. The soft-spoken Kaukonen has always conveyed a mysterious, almost spiritual quality best expressed in the grooves of a long-playing record. He’s been content to communicate evocatively through song. A tell-all tale of the Airplane’s adventures is not Kaukonen’s style, but the straightforward, conversational prose of his book insightfully describes a life every bit as packed full and intriguing as his expressive songs. “Music stirs memory in a singular way that is unmatched,” Kaukonen astutely muses. At the McDonald, Hot Tuna went straight to work confirming JK’s claim with a sinewy, swaggering riff reverberating with suggestive meaning.

Hot Tuna has taken many shapes and forms over the years, proving equally adept at both intimate, acoustic Americana and explosive, electrified rock-and-roll. In Eugene, they were plugged in and equipped for a high-energy howler. The trio sounded spry, even downright sinister on “Ode for Billy Dean,” from Tuna’s 1972 studio debut, Burgers. If there were any questions about the vitality of a couple of septuagenarian rockers from the “Summer of Love,” Hot Tuna crumpled them and lit them on fire with their blazing “Billy Dean.” Casady rolled thunder under Kaukonen’s wicked, atmospheric wail, and Jorma defiantly growled, “I’m still alive now, and I don’t worry/When I go down, don’t let me go slow.”

The group evoked a raunchy, edge-of-town roadhouse aura with the screaming Billy Boy Arnold cut, “I Wish You Would.” Kaukonen dug deep and demonstrated why he is often listed among the world’s greatest guitar players. He gave it the fuzzy, lysergic, “rock god” treatment and shot the song from its juke joint origin to a place decidedly closer to 2400 Fulton Street. Kaukonen is one of those important artists who bridge the gap between authentic, traditional folk/blues and the pinnacle of electric blues rock. JK begins with genuine, acoustic folk roots and spirals outwardly until he flowers in the land of Hendrix and Cream. At the McDonald, he displayed all the fiery, muscular, consciousness-heightened energy of Woodstock alongside an acute understanding of Mississippi Delta and urban, Chicago-style blues. Throughout the evening, Hot Tuna conveyed a “Night at the Museum” effect, where historic exhibits burst to life. “I Wish You Would” lit the theater with an incendiary, vibrant presence as if the “Mona Lisa” leapt off the canvas and boogied through the crowd.

A haunting version of “Trial by Fire” created one of the evening’s early highlights and showcased Hot Tuna’s captivating talent for storytelling. It also, amazingly, suggested Hot Tuna are still evolving. Among the best songs, Kaukonen penned for Jefferson Airplane, “Trial by Fire” displays JK’s proficiency with traditional folk motifs. Familiar idioms like “that bony hand comes a beckoning” implicitly connect the circumstances of the songwriter to an eternal, archetypal struggle expressed in folk-tales and myth. Appearing on the Airplane’s final studio release, Long John Silver, the track originally gleamed like a pick-up truck rolling down a country road. The buoyant, glassy-eyed shine of the 1972 recording bristles with youthful resiliency, unencumbered and running free. In Eugene, the song maintained a rustic amble but became imbued with a darker hue. The narrative remained resistant, yet more calloused than brash. The consequences had grown closer, and the weight of anguish had increased with age. Lyrics like “lying on the floor with a hole in my face and a ten-gauge shotgun at my head” echoed with jarring authenticity. The song sounded sincerer in the throat of an older man.

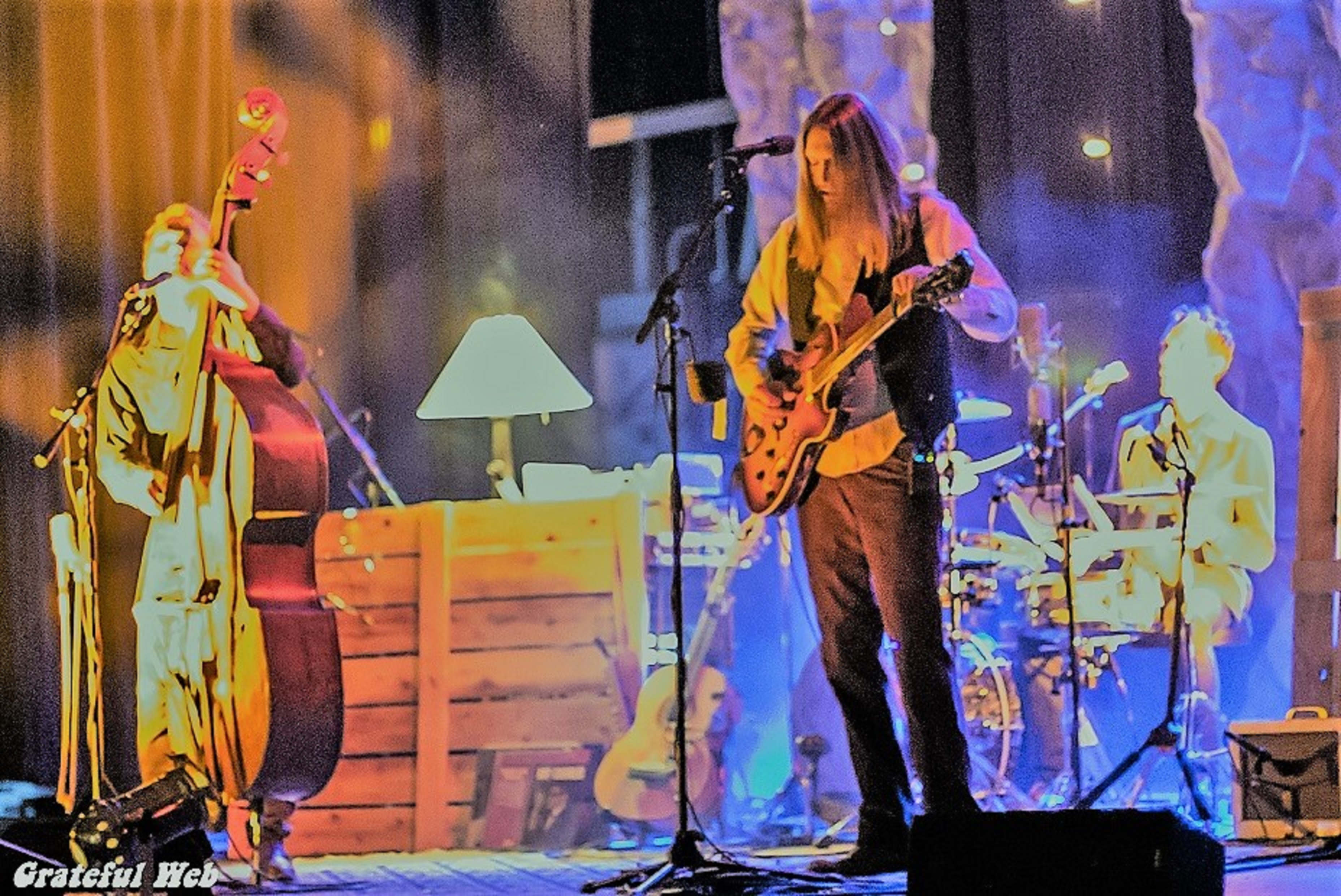

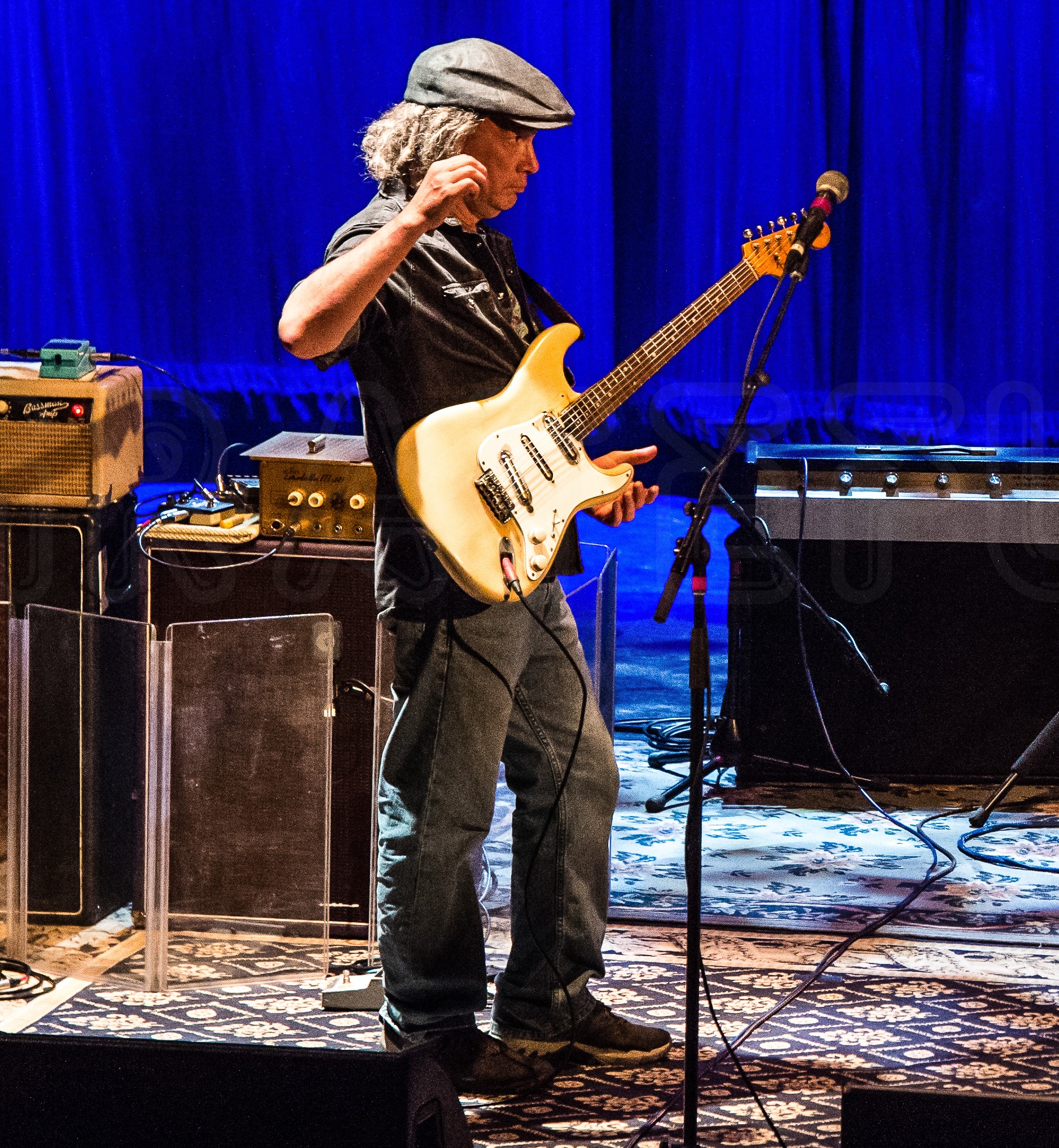

Special guest, guitarist Steve Kimock joined the trio for a fine finish to a terrific first set. Kimock, a decorated veteran of San Francisco’s jam-band scene, founded the group Zero with John Cipollina, and lent his talent to Keith and Donna Godchaux’s Heart of Gold Band, Phil Lesh, and Friends, as well as Ratdog, among others over the years. At the McDonald Theater, Kimock’s tasteful accents and added crunch helped Hot Tuna build another level on an already high-rising show.

A luminescent “Sea Child” featured Kimock on pedal steel guitar. Another fascinating Kaukonen composition, “Sea Child” mystically synthesized folk with psychedelia. Kaukonen’s ornate fingerstyle guitar merged a deeply rooted earthiness with the ethereal. Kimock’s shimmering emphases swirled with golden California vibrations. The song held the room in a warm embrace as JK pleasantly affirmed, “Reminds me once again/how nice it is to be with you.”

A double-shot of growling, groovy blues closed the opening set. First, Tuna’s scorching treatment of Delta bluesman, Walter Davis’ 1940 hit, “Come Back Baby” summoned demons from the crossroads and bathed them in fierce distortion. Casady’s bassline burned tire tracks on the floorboards of the theater with its supercharged, muscular thrust; and Kaukonen nearly assumed a power stance as his fingers triggered a crackling eruption of electricity.

Bobby Rush’s “Bowlegged Woman, Knock-Kneed Man” delivered another high-powered hit of amplified emotion. Again, Casady’s huge, pulsating presence gripped the room in a sultry trance. Kimock’s funky scrubs kicked dirt around the chicken coop before Kaukonen’s wolf arrived to satisfy his instinctive hunger. Hot Tuna’s barn-burning “Bowlegged Woman” indisputably confirmed the group’s explosive blues power.

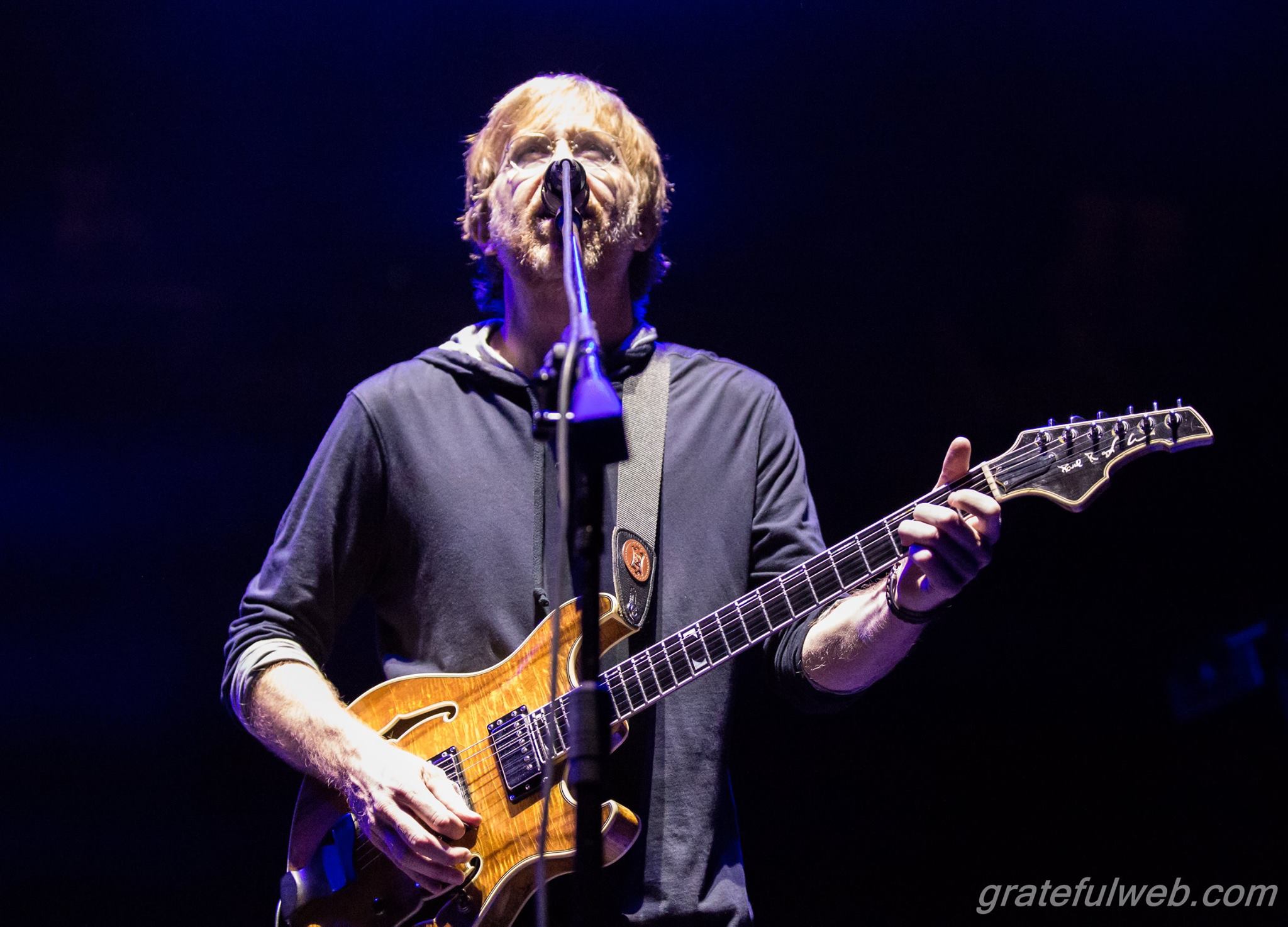

The first set was simply a primer, it turned out, because the second helping was truly lit. Hot Tuna revealed themselves to be more than amazing revivalists. They became illuminating shamen practicing an ancient art. The crowd hypnotically succumbed to Hot Tuna’s alluring mixture of vintage American styles. As set unfolded, a theme emerged—we were taking a trip, a spiritual journey that began appropriately with “Serpent of Dreams.”

From Hot Tuna’s 1975 release America’s Choice, “Serpent of Dreams,” established a heady, mentor/master, medicine-man vibe. Kaukonen and Casady blended elemental forces of fire and earth and flowed like hot lava. Kaukonen’s evocative fingerstyle guitar filled compliant heads with fanciful visions, and the lyrics intimated a transformation, “Serpent’s friends have come and gone, down the slopes they’re moving on.”

Fan favorite, “I Know You Rider” embraced the thematic journey, and once again emphasized Hot Tuna’s deeply embedded roots. The song’s churning, irresistible momentum collected any stragglers and unified the audience in a singular, hopeful assurance, “The sun’s gonna shine in my backdoor some day!”

“Roads and Roads &” jangled with genuine pop-rock sweetness, while “Watch the North Wind Rise,” another stunning display of Kaukonen’s multi-faceted technique, sauntered happily and promised, “We’re going home, won’t be long, hearing my song.”

“Roads and Roads &” jangled with genuine pop-rock sweetness, while “Watch the North Wind Rise,” another stunning display of Kaukonen’s multi-faceted technique, sauntered happily and promised, “We’re going home, won’t be long, hearing my song.”

“Good Shepherd,” from Jefferson Airplane’s 1969 album Volunteers, affectively initiated the show’s final phase. A traditional gospel, arranged by JK, “Good Shepherd” represents one of Kaukonen’s finest contributions to the Airplane. It is characteristic of Kaukonen’s trademarked synthesis of “flower power” and folk. In Eugene, the song resonated with historic importance. The lyrics’ religious overtones created a poignant turn in the set’s symbolic voyage. Hot Tuna were taking us to a threshold of spiritual enlightenment, “Oh good shepherd, feed my sheep.”

Perhaps to remind how close salvation is to sin, Hot Tuna unleashed a rabid reading of Robert Johnson’s “Walkin’ Blues.” JK flexed and stretched the blues to Filmore-era dimensions. The rhythm section was locked in the pocket of a filthy groove. The room throbbed in unison. “I’ve been mistreated, and I don’t mind dying.”

Another track from Tuna’s landmark America’s Choice record, “Hit Single #1,” blasted the theater with high-voltage rock-and-roll. Kimock returned to fan the flames, and the group tore into a free-flowing jam. Kaukonen conjured radiant waves of musical electricity. Seventy-four-year-old Casady bounced and pounced across the stage like a randy alley-cat. The band was in full flight and obviously enjoying the ride.

Casady, the crawling king snake of vintage rock bass players, threw down a bumping, bone-rattling introduction to “Funky #7,” the final song of the second set. Casady, a fascinating character and gifted musician in his own right, seems to exist solely to wrap his fat, fluid basslines around Kaukonen’s expressive leads. JC and JK are one of rock’s dynamic duos, mirroring in many ways the musical marriages of other psychically linked artists like Weir and Garcia, Lennon/McCartney or the “Glimmer Twins” (Mick Jagger/Keith Richards). The two have known each other and collaborated since high school. Casady joined Jefferson Airplane on Kaukonen’s recommendation, and when the Airplane finally fractured into separate, distinct entities, Casady remained with JK to become a foundational cornerstone of Hot Tuna. Casady and Kaukonen share a Vulcan mind-meld type of understanding. Casady surrounds Kaukonen’s ideas and intuitively fills the empty spaces. While they’ve both played with other artists, it’s almost impossible to imagine one without the other. They comprise complimentary elements of the same work of art.

Hot Tuna worked “Funky #7” into an ecstatic torrent of delirium. It was the climactic, rapturous release. No rock-and-roll salvation is worth its salt without joyful exaltation. Kaukonen stepped on his wah-wah pedal and accelerated the process. Liquified notes poured from his strings and splashed the awed faces of the audience, a baptism by guitar. It was not a quiet sermon. The group stood on hind legs and roared. They eviscerated skeptics and left only admiring believers.

Those who remained for the encore were treated to magical version of Tuna’s instrumental masterpiece, “Water Song.” In a final exhibition of their uncommon expertise, Hot Tuna didn’t simply play “Water Song” as much as they coaxed it out of the shadows and allowed it to play them. A delicate, dabbled creature, “Water Song” flowed through the theater and elicited a stunning “wow.”

Tecumseh once said, “When the legends die, the dreams end; there is no more greatness.” Hot Tuna’s scintillating Eugene performance emphatically established “greatness” is not yet extinct.