The Dark Side of the Moon – Pink Floyd’s time-honored concept album with an ominous pulse from start to finish – came screaming into the world like a proverbial newborn, seemingly fully formed and full of life, on March 1, 1973.

Fifty years. Doesn’t it seem like no time at all?

For some of us, it was, indeed, a lifetime ago.

Yet, the timeless and improbably massive hit album about life, death, greed, madness, and man’s inhumanity to man – and not the Moon at all – began with a faint, embryonic heartbeat, less fleshed out than you might think, sometime in the waxing winter days of late 1971.

That was actually 51 years ago, if you’re keeping score at home. But, by some accounts, it may have even been much earlier.

Only a short time before, I was an infatuated 15-year-old fan of ‘progressive rock,’ which was in full bloom on ‘underground’ FM radio in the late 1960s. This included the realm of everything from Creedence to Crimson. Then, one evening in the late summer of 1969, I stumbled upon this singular band’s otherworldly sound on my local FM rock station in Cincinnati.

Hearing “Cirrus Minor” – a hypnotic folk ballad from the band’s soundtrack for the arty foreign film More – was my portal to Planet Floyd. It was a deeply quiet acoustic song. But the hook for me was the haunting church organ conclusion. In very short order, at two Cincinnati shows in 1971 and 1972, I was able to witness PF’s early live experiments that gave birth to Dark Side, the eventual record-shattering masterpiece which has almost always dominated lists of top prog and concept albums.

Like a gestating zygote, a mass of musical ideas that would become DSotM slowly grew more delineated behind the scenes with every tour, every new soundtrack gig and every new group album the Floyd released, from early 1969 to fall 1971.

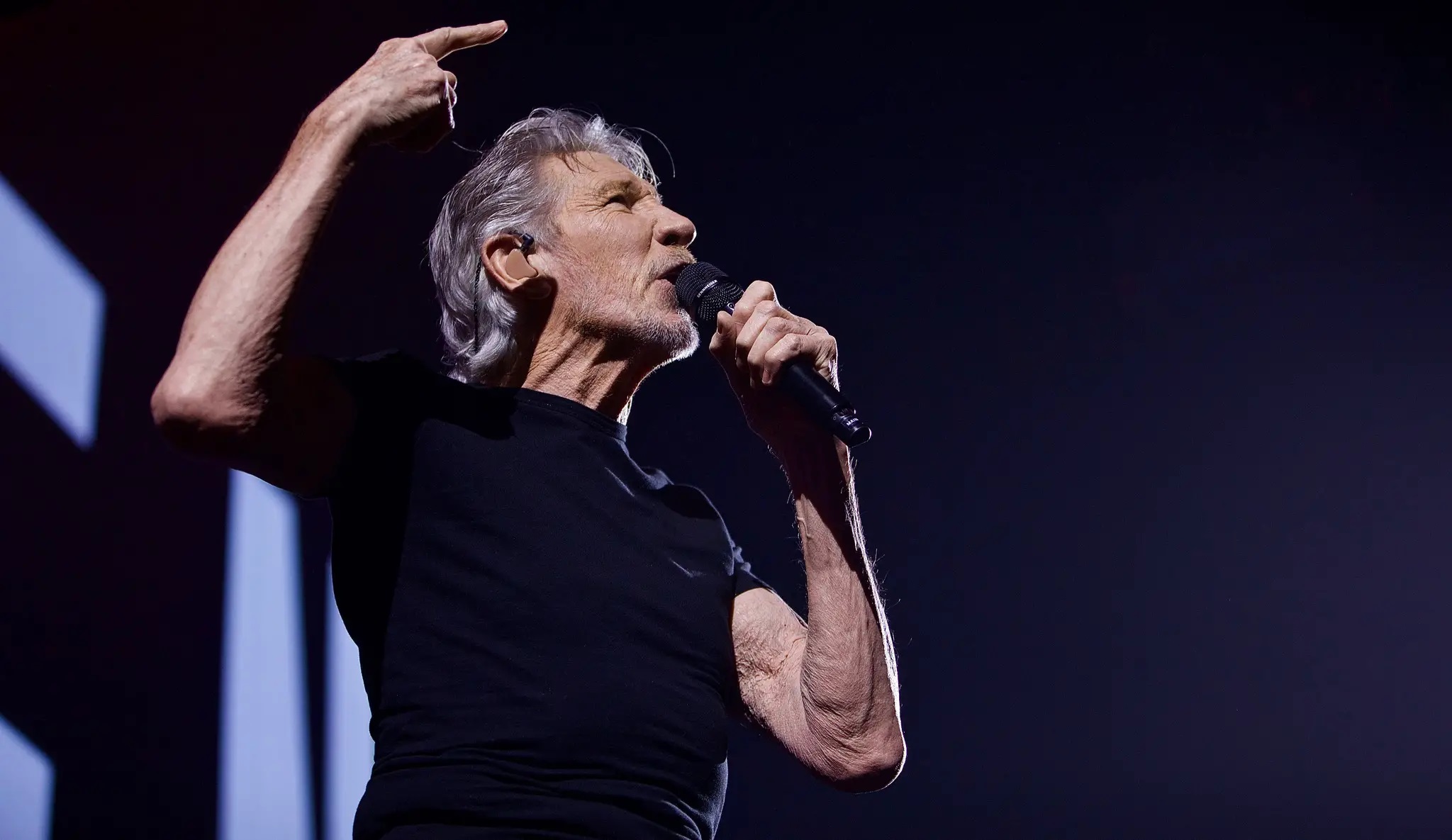

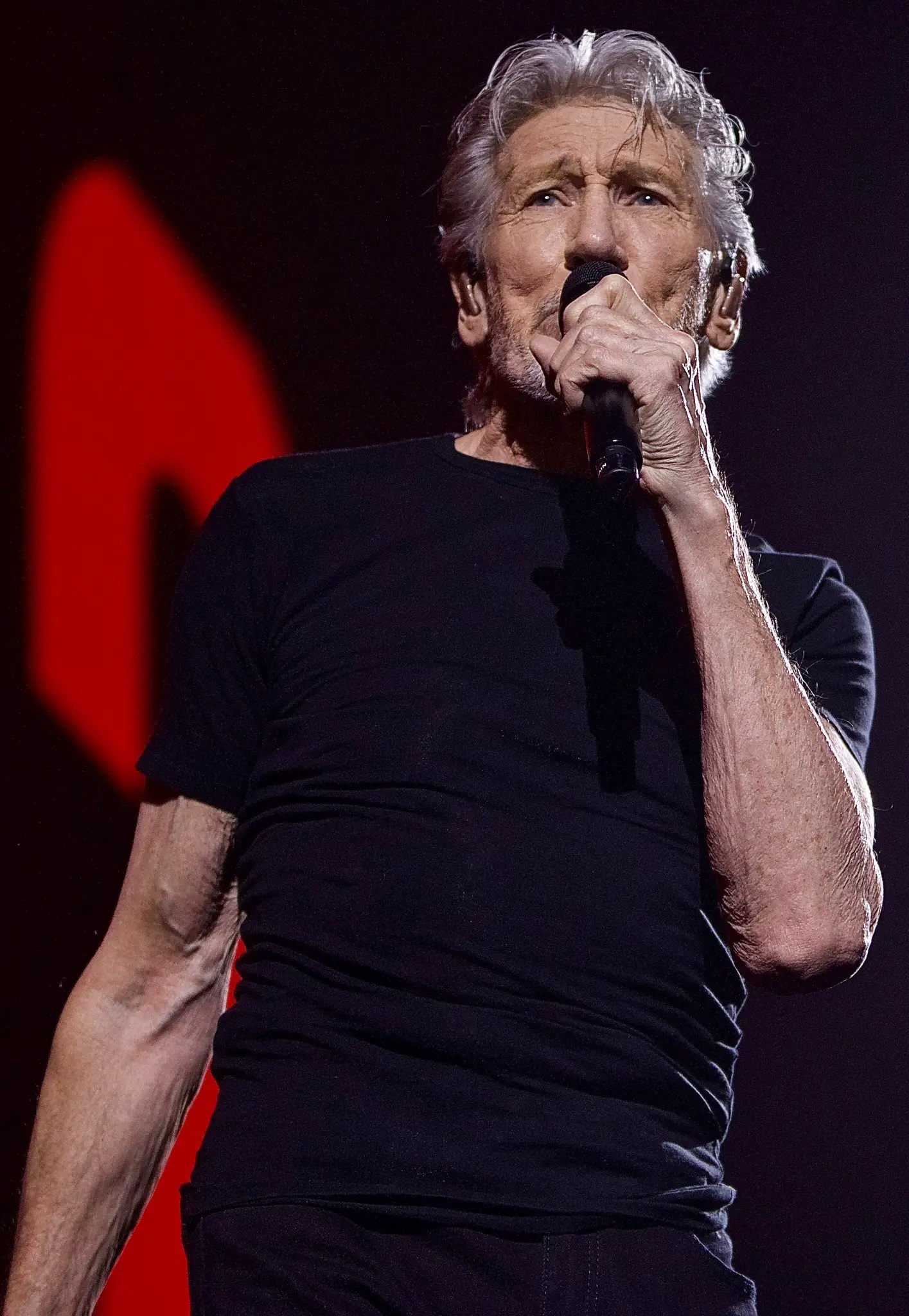

So, let’s tally it all up. Seven albums – three of them soundtracks – and touring whenever they could, not to mention filming a performance movie of their own. All of that – just within a three-year span– proved that, yes, there was a damned lot of percolatin’ going on. And Floyd bassist/songwriter Roger Waters finally ‘saw the whole of the Moon’ in late 1971 and pitched the concept to his bandmates soon after the conclusion of their just-completed fall tour of North America.

There was hardly time to breathe, it seems.

My chance to experience a live performance of the early Dark Side – cryptically known then as Eclipse: A Piece for Assorted Lunatics – came on April 23,1972, a night that forever baked in my perceptions of the band. And – heh – as any Deadhead knows, the ‘live’ version is always better, especially when it’s an early taste like the one I had. (The album rolled out many notable changes from earlier versions that had taken this early Floyd adopter a bit of time to accept. But that’s my trip, baby.)

So, if you don’t mind, let’s all take a deep dive into Floydian history as it all led to, and followed from, The Dark Side of the Moon.

As they say, buckle up, Buttercup. . . .

The Journey to the Center of The Man

Soon after the official release of Dark Side in March 1973, Roger Waters – lyricist and chief conceptualist for the album – proclaimed in an interview that the Floyd had “finally cracked it.” He meant, of course, that they had created a seamless song cycle, unified around a central theme, that seemed to flow effortlessly from one song to another in a way that often compelled one to listen to the album in its entirety. And it connected with a large number of people, in a very short time.

Of course, the album’s ‘overnight’ success ensured the band’s mass-market breakthrough after they had bubbled underground for several years in the superheated musical rollover from the ‘60s to the ‘70s. The album went on to set records by staying put on the Billboard Top 200 List from 1973 to 1988, and selling more than 45 million units to date. So this ‘cracking’ was the simultaneous eruption of wider creative and commercial success that had kept eluding the band in their early working years.

It was, indeed, an explosive event.

Other rock artists, most notably The Beatles, The Who and the Moody Blues, had been leading the charge with thematic albums in the late ‘60s and, to say the least, reaping critical approval and popular success. Some of PF’s more experimental peers, such as the Pretty Things, had also created acclaimed thematic works but had ended up with only cult recognition. And in the late ‘60s, the Floyd had found themselves in limbo between those two extremes – a cult band on the verge of breakthrough. Only time would tell their fate, whether that would be as merely footnotes or as full-on legends.

In the years immediately after Floyd founder Syd Barrett’s untimely 1968 exit due to his tragic descent into mental illness, PF struggled through a collective soul searching. Were they a singles or album band? Pop or progressive? Entertainers or artists? Would they even survive?

So many questions, not easily answered. But the band plugged on. And the former psych-pop stars did consciously – and successfully – recast themselves as progressive album artists. It was, in fact, a process which took them nearly five years to work through.

The record company heads, of course, wanted more singles that would shine like their early Barrett-written hits, but the men of Floyd heard a different calling. With replacement guitarist David Gilmour on board since early 1968, PF embraced longer-form compositions as staples of their live act and also began honing their stagecraft.

At first, PF exploited their core sound of wigged-out space-rock but quickly began to chafe under that label. So, eager to branch out, they dabbled in blues, jazz, classical, folk and other textures – even a touch of country – while still hewing closely to their psychedelic roots. Furthermore, they extended their scope with electronics and quadraphonic live sound, and introduced a few dramatic visual elements for their live shows.

Subject matter quickly ripened in this period as well. PF’s lyrics began to reflect more concerns with futurism, humanism and politics – a trend that turned obsessive for Waters as he settled in as chief songwriter. Some have fittingly called this thematic shift a change from ‘outer’ to ‘inner space’. (For his part, Waters once had already dismissed ‘space rock’ in an early ‘70s interview as an absurd concept. “There’s no f’g sound in space!” he said with typical finality.)

Still, within the band, there was ongoing creative tension between those who pushed for musical values and those who pressed for more structure, effects and presentation. At the heart of it was a struggle with The Meaning of It All. Beginning with the various 1972 tours, the band distilled all of these elements into one compelling concept.

As seemingly effortless as the music of DSotM has always sounded, its conceptual flow was not conceived of in one discussion, as such, In reality, it had evolved rather naturally from the time of Barrett. And so the arc toward conceptual unity was incremental, over multiple albums. A few early PF tracks were compounds of different sections, but usually no more than three parts.

Soon after the band’s North American tour in 1971, though, Waters did have a flash of inspiration, leading to a tentative running order using both new and repurposed songs. And by the end of that November – scarcely a week from having just coming off the road – the band was already trying on the new set in rehearsal. Another tour in England would be starting on January 20 of the next year, and the band would have to work quickly if they wanted to have a new set of songs ready by then.

Vague ideas about the puzzles of life and formatting songs together had been lurking in the background. And the pressures of constant work had begun to weigh down on all of the band, but on Waters most of all. With Barrett’s own failure to ward off his mental demons in mind, Waters had been churning over many of his own experiences as a touring musician.

Pressing social issues, such as world poverty and the Vietnam War, agitated him, too. So when he turned to the lyrics, all of the now-well-known, interlocking themes – birth and death, the pressures of time and money, hate and conflict, and the fear of madness – emerged. This meditation on personal existence became a musical mirror in which countless millions of fans could see themselves.

It was, in fact, not the Floyd’s first ride on the storytelling seesaw. In mid-1969, for their live stage shows, the band had briefly experimented with a similar sequencing. Mingling pieces from their 1968 album A Saucerful of Secrets with others from the More soundtrack and material that would soon appear on their 1969 double-album Ummagumma, they had mounted a stage concept called The Man and The Journey. (For an early staging in April, 1969, the show was titled The Massed Gadgets of Auximenes – More Furious Madness from Pink Floyd.)

Some music journalists have referred to The Man and The Journey as the “great, lost Floyd album.” This label was fueled, in part, by the existence and circulation of audience recordings (I hear they are called RoIOs – recordings of illegitimate origin. . . .but I’ll call them archival.) of the band’s August 1969 performance in Amsterdam and broadcast on Dutch radio that year. And, indeed, the concept could have become an album, if even just an official live recording. But, in the end, the band made other plans.

Nearly all of the songs used in The Man and the Journey have been recorded and released as isolated tracks over various Floyd albums. But, until the release of the official PF box set The Early Years, in 2016, most PF fans who hadn’t seen those shows had scant awareness that such an early Floyd song cycle had ever existed.

Heartbeats, Atoms & Echoes

Both the surrealistic 1970 movie Zabriskie Point by Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni and the accompanying soundtrack album featuring a handful of PF compositions began with a loud but arrhythmic heartbeat. Titled “Heartbeat, Pigmeat”, this instrumental track hinged upon two functional devices that the Floyd later used prominently on Dark Side – an insistent pulse and salvaged, spoken-word TV audio clips woven into the mix. It definitely sets a vibe of foreboding in this hallucinatory anti-establishment art film.

Another Waters-related project of the time – not a full-fledged Floyd album, though – tagged along shortly after the Fall 1970 release of Atom Heart Mother. This was a soundtrack for an animated movie about human physiology titled The Body. Waters had been invited onto this project by eccentric British composer/arranger Ron Geesin, who was also arranger for AHM’s title track. So there was timely overlap.

Essentially a visual travelogue of the world beneath our skin, this film featured a few lyrical songs amid various quirky sound collages, instrumental splashes and vocal nonsense that represented, um, bodily functions. Notably, the album contained a brief guitar ballad called “Breathe.”

Although not the same song as the eventual Dark Side tune of the same title, its melody was similarly bittersweet. This scattershot soundtrack, Music from The Body, also ends triumphantly with the power-ballad “Give Birth to a Smile”, also based on the same chords of that “Breathe.” Thanks to this uncredited inclusion of Waters’ three other PF bandmates and female vocalists on this rocking finale , “Smile” boasts a beefy David Gilmour solo that almost makes it sound like a Dark Side outtake – two years in advance!

The bodily theme was also present in PF’s own Atom Heart Mother album, from earlier that fall. The title track – having emerged in the band’s sets early in 1970 and then augmented by classical musicians – was the band’s first recorded move toward more stratified form and function with a 20-plus-minute suite of interconnected passages.

The piece had undergone several name changes along the way. But, before a major broadcast of a live performance on a BBC radio program in mid-summer 1970, PF members spied a newspaper headline. It announced a pregnant woman had been fitted with an atomic-powered heart pacemaker. So the piece got an instant name change on the spot.

Indeed, grafting an orchestra onto a rock framework did prove daunting for PF. And though nearly all participants in the project have dismissed it as a flawed experiment, it clearly provided a learning curve for the band as they sought to give shape to their often sprawling sonic tapestries.

The next PF LP in line – 1971’s Meddle – seemed at first listen to follow a similar blueprint as AHM – a side of scattered rockers, ballads and pop pastiches, and a multi-part composition that would take up a side. Except this time the Floyd had flipped the side-long track to the back half, allowing Side One to set the stage for the Main Event, rather than having it lead in.

Unlike AHM’s title track, which integrated the band, quite unevenly at times, with classical musicians, the long suite on Meddle – more simply titled “Echoes” – was generally more streamlined. As a return to the four-man form, this piece saw the band creating all of the music on their own. Most notably, this made it easier for PF to perform it live, without having to keep an orchestra in tow.

The fair consensus among band members, music critics and legions of admiring fellow musicians from down the years is that “Echoes” was PF’s pivotal composition and recording. And, certainly, without PF learning the lessons of turning their 24 raw sections (The band’s working title for “Echoes” was “Nothing, Parts 1 to 24.”) into a polished musical mosaic, Dark Side simply might not have ever come together.

“Echoes” was a remarkable advancement for Waters especially, as it helped him to stretch his lyrical skills. Being an instrumental suite, “Atom Heart Mother” did not require a narrative vocal layer. (It did have choral passages and a section of inscrutable chanting.) And the only songs for which Waters had supplied lyrics before were shorter rockers and ballads. So now, he had been tasked with writing something more poetic, even spiritual. And, perhaps with a slight lyrical echo of his musical hero John Lennon, Waters came through with a sweeping declaration of universal empathy (“I am you and what I see is me. . .”) that rose to the scale of the piece’s grandeur.

This was the same task that the then-still-maturing lyricist would be faced with again with DSotM. According to various PF history sources, the sequence had been mapped out well ahead of the lyrics. This left Waters with only one mission: “To go write the [f’ing] words. . .” And as Gilmour would later remark about Waters in an interview, it was “he who deliver[ed] the goods.”

The Floyd’s first live attempt of the suite destined to become DSotM came in early 1972, on January 20, in Brighton, England. Unfortunately, the audience did not get to experience the entire composition the first time out.

Reportedly, the power failed at this gig – just 26 minutes into the show. It was an unfortunate event that Waters has described as a “horror.” With no choice but to abandon Dark Side for technical reasons, the band dutifully carried on, subbing in a band version of “Atom” in place of the second half, plus other routine pieces.

And this first DS version – which we now know was one song shorter at this early stage – still lacked the well-known and recitative conclusion that sums up all of life’s quandaries raised in the preceding songs. This song, of course, is “Eclipse.” Before Waters added this final brick in the song series, DS had concluded with “Brain Damage.” The first ending had the music disintegrating into a cloud of warbling guitar and organ tone-generator groaning, not unlike Keith Emerson abusing a Hammond organ. (No synthesizers yet. . . .) Perhaps this was meant to represent a kind of mental breakdown.

Of course, “Brain Damage” is also the song from which the multi-part suite had drawn its original name, Dark Side of the Moon. Unfortunately, the band had soon found that the UK band Medicine Head had an identically-named album. PF’s Plan B was then to rename their suite Eclipse: A Piece for Assorted Lunatics. No confusion there! Touring well into late spring that year, the band would simply announce it on stage as Eclipse.

Once sales of their competitor’s product proved lackluster and unlikely to cause name confusion among the public, PF cheerfully resumed calling it DSotM. (Note: It was only many years later that the word, The, was added to the title complete the official name.) In any case, the piece made its public debut as Dark Side of the Moon on PF’s Fall North American tour that September.

Embryonic Envelopment

Even before its first public performances in early 1972, DSotM took form at the molecular level in several key stages. One unforeseen step for the Floyd was their work-for-hire assignment on the 1970 Zabriskie Point soundtrack. Although PF had originally been hired to create the entire score, the film’s director Antonioni had famously grown dissatisfied with PF’s submissions. Only a few PF pieces would be used in the final film. Notably, this opened the door for the Grateful Dead and Jerry Garcia, among others, to also be ZP contributors. (The 2016 PF box set The Early Years has gathered up most of the PF outtakes in one batch.)

Within the Floyd there was a prevailing work ethic and a desire not to waste any song remnants. Quite often, bits from side projects and live improv would find their way into new compositions. Sometimes, there were even full songs. Two songs that became part of the DSotM sequence were an in-progress Waters track from the Meddle project said to be titled “The Lunatic Song” and an abandoned Richard Wright Zabriskie piano instrumental, “The Violent Sequence.” These songs became “Brain Damage” and “Us and Them.” A few others that soon got slotted into the DS order came out of ideas the band had been trying out in live shows over the preceding year or had just written.

It has always been personally striking that a key composition in the early days of DS is one that actually didn’t make the final cut, a melancholy song titled “The Embryo.” (No, the Floyd didn’t save everything.) With lyrics from the point of an unborn child, this song had a split personality. An unfinished studio version – inadvertently released on a 1971 sampler by Harvest Records titled Picnic –was a hazy almost-lullaby. But as a live piece in the 1971 period, it became a dramatic, acid-blues-rock number, with fiery peaks and dreamy interludes. Longer live versions did not become available until the 2016 release of the Early Years box set.

On November 20, 1971, the Floyd performed at Cincinnati’s Taft Theatre during their fall Meddle tour. (Especially fateful for me, since it meant my being able to see the band live for the first time. And it was also the last night of the tour.) Although one might have expected Meddle’s opening track “One of These Days” to kick off the show (I certainly did!), PF chose to lead with a spectacular, meandering version of “The Embryo."

As the song unfolded, it was impossible to tell in the moment that anything had gone wrong. (The problem was only pointed out after the song’s completion, almost a half hour into the concert.) Sometime during a trippy, two-chord, minor-key interlude that came about 16 minutes in, the band had suffered a partial power failure. The bass and keyboards had gone MIA, but, despite the glitch, the guitarist and drummer plugged on. Then, unplugging his bass, Waters strutted over to Gilmour’s Hi-Watt stack and jacked into a second channel to join the rudimentary jam. (On available audience recordings of the show, there is obvious cheering at the exact moment when he crosses over. Moments later, his bass comes thundering in.)

The trio jammed on gamely for some 10 minutes in a cosmic-bluesy E minor/A major groove reminiscent of such slow, quarter-time songs as “Down by the River.” Finally, Wright’s keyboard juice was restored and he was able to slip back in for a triumphant ending. The band carried on after a brief pause for a full technical check, then cycled through much of their standard set, which included versions of both “Atom” and “Echoes.” Naturally, both are songs that rely on extended slow passages. And the band even offered up a slinky, 12-bar blues encore. It, too, was in quarter time.

Around this time, drummer Mason shared his observation in a Circus magazine interview that PF’s live set had been getting a bit long in the tooth, and that, as a whole, the band were at risk of bogging down in “certain Floyd clichés.” Among them, he noted, were two-chord jams, flogging the same phrases repeatedly and good, old “slow four” time. Perhaps the Cincinnati show was still fresh in his mind?

Once Eclipse came into the world in early 1972, it was immediately clear that although Mason’s peeves had surfaced in “The Embryo”, now the Floyd were extracting them from such interminable jams and bending them to their will in smaller, more digestible portions. Thus, it was easy to imagine that Waters’ new “Breathe” lyrics could have been married with “The Embryo”’s minor-key progression, ensuring that the Piece for Assorted Lunatics would be ready for January 20. In hindsight, it would appear that – in the space of only a few weeks – “The Embryo” had truly grown into a brand-new baby.

Walking on the Moon

“Maaann, that bass player is [f’d] up,” one audience member could be heard talking smack about Waters in a disbelieving tone on the way out from the Floyd’s April 23, 1972 show at Cincinnati’s Music Hall. Maybe it was a compliment? A few days after, a reviewer for a local newspaper also called it a “mind-frying show” but griped about the music playing second fiddle to the effects. Not so complimentary, eh?

This had just been my second Floyd show, and I was equally dazed but also confused by what I had just experienced. Well, there was definitely a lot to take in this time – a few older songs got played, but not nearly enough for me! But there was also a whole new set in the first half, and so much going on in it. And, not surprisingly, there was a pungent odor and haze again choking the air – just like at the November show. (It was still the early ‘70s, after all.)

So, yes, the production elements were a huge jump from the minimal lighting and effects used in the November show. Mechanical towers of multi-colored lights, dry-ice clouds, flashing red police lights, special sound effects and insane laughter on the quad system, and flash-powder explosions leaving plenty of smoke in the air. (I had wondered during pre-show what those small waste bins atop the amplifier stacks were for. But the shock wave and heat hitting my face in the front row answered that question, all right.) And, of course, for the f’d up parts, there were the usual, wild Waters gong-banging moments in “A Saucerful of Secrets” and blood-curdling screams during “Careful with That Axe, Eugene.” Highly visual, if not outright shocking, to say the least!

And the music? Well, I wouldn’t be reading that critic’s review until the smoke had cleared out of my mind the next day, but I sensed right away that this strange new material in the first half was, indeed, very musical and a quantum leap over either “Atom” or “Echoes.” (The latter was also played in the second half, so there was definitely a chance to compare notes.) For example, it was twice as long as either of those pieces. It just wasn’t what I had gone in expecting to hear!

Entering the theatre that night, my small group and I could see a trio of retracted, unlit aluminum hydraulic light towers along the wings and back center of the stage, not to mention the Floyd’s trusty gong standing guard by the drums. The towers would soon fire into action, though.

New instruments were on the stage, too: For instance, a prominent second organ Leslie speaker next to Gilmour’s rig, a second microphone stand next to his main mic (What’s that for? I wondered aloud.), Rototoms flanking Mason’s usual psychedelically-painted double-kick drum set and what appeared to be an ever-growing arsenal of keyboards on Rick Wright’s side of the stage. (One was a shiny new Fender Rhodes electric piano.)

Gilmour and Waters also each had a new matching Fender guitar and bass with black-and-white solid bodies and blonde-maple necks, And Gilmour also had himself a double-necked Strat – used on “One of These Days” – to the side of his amp.

The band’s 360-degree sound system was visible, too, with speaker cabinets placed at intervals around the stately theatre, and on both balcony levels to boot. (PF had used a quad system in November, too. This one was quite possibly newer and more powerful.) An ominous heartbeat began pulsing shortly before the band emerged, and it panned the room via the multi-channel speaker array. A shock wave of applause went through the hall.

A mechanical drone began to hum in the speakers, too. And when the house lights went down and the band came on, the light towers came to life, rising and pulsing in a bright, mechanical swell. This triggered many gasps, oohs and ahhh from the audience. Very much like the arrival of an alien Mother Ship, it seemed to me. (On a now-released archival recording from the Chicago show a few days after Cincinnati, you can hear a fan wisecrack right before the music starts, “Beam me up, m-f’ers!”)

As the band leaned hard into the opener – a slow-tempo’ed E minor dirge that was highly similar to “Atom Heart Mother” – I soon realized there was no orchestra behind the curtain and there’d be no “Atom” this night. (A secret hope of mine!) After this roughly 50-minute ‘song’ without a break was over, Waters said, “That was a new piece titled ‘Eclipse’. Now, we’re going to take a short break.” I felt a sharp pang of disappointment: Damn! They’ve done it again! Taking up too much time with new songs and not playing what I want to hear! Picture that, right?

What had we just heard? I had no idea at the time, of course, but thanks to the magic of archival audio and the benefit of time, we learned that the bulk of Dark Side’s arrangement was very much in place and quite well developed. The live refinements would continue throughout the year, well into December. And the band would soon heading for the studio to start assembling and tweaking the final recorded arrangement. A few blocks of time got wedged around constant touring.

Yep, the two-chord pattern that served as filler on “The Embryo” back in November was there again, providing the main form under the verse of what we have since learned was “Breathe." Before even a word was sung, Gilmour squeezed out a ragged blues lead on his Strat over the opening bars. And even though he smiled as he sang, it was spooky music, full of pain. And it was just getting started!

The minor-key harmonic space continued into the next couple of sections, with a propulsive jazz-fusion jam featuring a Chick Corea-like Rhodes piano solo from keyboardist Wright. A sound effect of something sounding like a clacking rollercoaster whooshed around on the room on the surround system, adding a vivid sense of motion. Next came a slow-building, Far Eastern-flavored soundscape, with a dramatic Rototom intro from Mason that soon turned into a slow but chunky Hendrix-like blues-rock groove.

During the intro of this piece which evoked images of Japan in my mind, Waters plucked ghost notes in a tick-tock rhythm with his bass strings pressed against the pick-ups. And the tune that Gilmour and Wright sang was tinged with more regret. In the choruses and under the heart-wrenching guitar solo, Wright added sweet, xylophone-like tones from his Rhodes. Then, finally, came a reprise of that world-weary main melody from the beginning of the show.

At what was actually only the halfway point (How could we know?), this mysterious piece seemed to be nearing the end with the return of that opening melody. Then, Gilmour sang a line about a “softly-spoken magic spell.” The stage lights suddenly dimmed as a funereal church organ passage gave me chills – just like the first time I had heard “Cirrus Minor”! Murmuring voices of people reciting prayers and sermonizing turned the concert hall into a cathedral! This lyric-less section was really a showcase for Wright’s sombre tone poem and the Floyd’s quad system, but Gilmour graced it with an achingly beautiful slide guitar line.

It certainly seemed that in this ‘story’ – if that’s what this long, drawn-out piece was – someone had died. Next, the loud sound of shuffling coins – in mass quantities – pinged about the quad system, creating a cloud of noise. Was it the sound of a collection baskets being emptied? Churches and money, of course – I laughed at that thought.

This bled right into the next song, a straight-ahead rocker with a chunky bass lead-in. The singers sang refrains in unison, and Gilmour clearly snarled out the word “bullshit” at one point. Wright played a fuzz-keyboard part just before the middle section with his old standby, the Farfisa organ. And this jammy song, which featured extended blues soloing by Gilmour over a driving beat, soon peaked and faded at the end.

Another ‘churchy’ passage floated in with audio of a sobbing woman set over a fluid organ/bass/drum groove. Gilmour and Wright supplied airy, bittersweet vocals on the verses. In the instrumental section, Waters decorated the octaves with a few false harmonics on his bass as counterpoints to the organ melody. Then, on the wordless chorus, the vocalists suddenly raged in again. Such dramatic swells seemed to signal that an emotional ending was near. But, again, it was just more tension and release.

Next up was a lengthy, rolling instrumental based around another two-chord shuffle – not unlike the opening melody. This, I thought, must be the final blowout - it was nearing the 45-minute mark now! First drifting along, with Waters doing a bit of exploratory lead bass, the watery jam flowed right in. Gilmour shadowed his bluesy leads with scat vocals, which had a special talk-box like effect. This distortion, which exaggerated the mocking tone in Gilmour’s voice, came from that mysterious second vocal mic being jacked through the second Leslie.

Aside from that sonic weirdness, the jam also crackled with chemistry. But no one actually soloed – it was all very much give and take, with Waters answering Gilmour’s smeary blues leads with short, punchy bass phrases. After a fevered final peak, they dropped smoothly into a humorous, Beatlesque ditty that mentioned “lunatics” and “daisy chains." (Yeah, we all know now what that was. . .)

Near the 50-minute mark (I stole a glance at my watch right then.) a definite aura of closure (finally!) came with a repetitive recitation that seemed to get louder with every new line. Gilmour and Wright harmonized with Waters in a heroic swell that sounded as if they were pleading with the audience to relieve them of a great burden.

It was capped with a breathtaking ending. The loud clang of a tolling church bell, flashing red lights, a piercing siren, and the hydraulic light towers blinking off, receding downward and finally turning off. We in the audience, not having had any real break to applaud between songs, all leapt to our feet, roaring with approval.

Neither I nor my group nor anyone else attending could have known at the time, but on that very night in 1972 – when Apollo 16 astronauts were literally still walking on the Moon! – Pink Floyd had just taken us to The Dark Side.

Next time, in Part II: We’ll revisit the massive 1973 success of the Dark Side album, how the perfectionism of their recording process and the album’s success changed the band forever, and the album’s lasting legacy and influence with new generations of fans and musicians.

In the mean time, thanks to the recent, now-official release of 18 archival audience recordings on streaming platforms, you can – for a limited time – listen to the in-progress live versions of Dark Side. You can make up your own mind about what did and (maybe) didn’t work in the original arrangement. You can find and stream these shows from Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube Music and such public library services as Freegal Music.

Dates of the featured shows include the following:

-

- Live at Southhampton Guildhall, U.K., Jan. 23, 1972

- Live at the Rainbow Theatre, London, U.K., Feb. 17-20, 1972 (4 nights)

- Live at the Taiikukan, Tokyo, Japan, March 3, 1972

- Live at Osaka Festival Hall, Japan, March 8, 1972

- Live at Nakajima Sports Centre, Sapporo, Japan, March 13, 1972

- Live at Chicago Auditorium Theatre, U.S.A., April 28, 1972 (“Beam me, up. . .”)

- Live at the Deutchlandhalle, Berlin, Germany, May 18, 1972

- Live at the Hollywood Bowl, Los Angeles, Sept 22, 1972

- Live at the Empire Pool, Wembley, London, Oct. 21, 1972

- Live at Ernst-Merck Halle, Hamburg, Germany, Nov. 12, 1972

- Live at the Palais des Sports, Poiutiers, France, Nov. 29, 1972

- Live at the Palais des Sports de L’ile de la Jatte, Saint Ouen, France, Dec. 1, 1972

- Live at the Vorst National, Brussels, Belgium, Dec. 5, 1972

- Live at The Hallenstadion, Zurich, Switzerland, Dec. 9, 1972

Additional: Dark Side will be honored in a brand-new book to be released in April 2023. A new luxury box set containing a re-release of the album together with numerous related music items and formats is also said to be on schedule for release at the same time. This information will be updated when exact dates are available. And keep your eyes open for the schedules of your favorite PF tribute bands, as announcements are coming weekly now about special Dark Side-themed tours.