In March 1973, something like floodgates opening happened for Pink Floyd when their then-brand-new concept album, Dark Side of the Moon, was set loose upon an almost unsuspecting world. Tuned-in fans of the then-still-cult band who had heard the live ‘draft’ version – still known well into mid-1972 as Eclipse: A Piece for Assorted Lunatics – on a hefty clutch of spring dates were breathlessly awaiting it. And the rest of the rock-music fans were about to become properly acquainted with the Floyd for the first time when those gates opened.

In June 1972, a new PF album named Obscured by Clouds – the soundtrack for the French art-house film La Vallée – had quietly arrived on record store shelves. Rabid fans expecting the magical new piece quickly scarfed it up. But. . .major fake-out. Obscured had only contained a loose series of soundscapes, soft ballads and a couple of nutrockers. It was a tad less exotic, maybe even a bit more tuneful than More – PF’s earlier project with the same director, Barbet Schroeder. By Floyd standards, ObC was – shall we say? – more ‘efficient’ than usual, and the fanbase’s eager embrace did visibly perk PF’s record sales. Happy band, happy record company. Double-plus good.

Nope, this wasn’t that sprawling, multi-song opus we thought it ‘shoulda been.’ In fact, we’d have to wait until early spring of 1973 to get the real deal in our hands.

The March of the Floyd

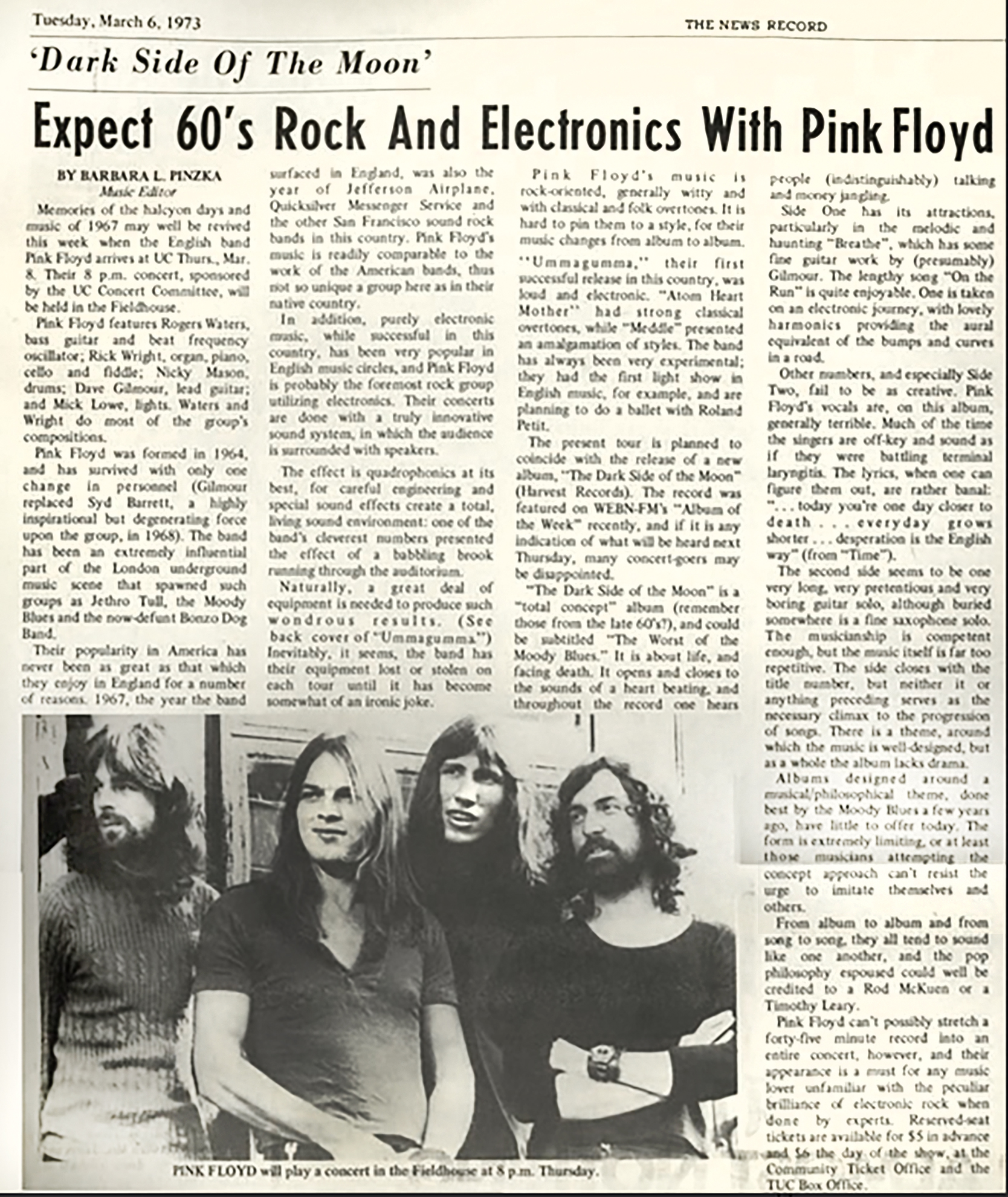

In early February 1973, a newspaper ad in Cincinnati’s Sunday newspaper announced a scheduled PF concert for Cincinnati. It would be on March 8, at the UC Armory Fieldhouse, an 8,000-seat sports arena on the campus of the University of Cincinnati. (This venue had also hosted the Grateful Dead in April 1970, but my family had strictly forbidden 16-year-old me to attend that show. Hippies and drugs, y’know. Not much changed in three years, either.) It had been nearly a year since PF’s triumphant 1972 Cincinnati performance at the 3,500-seat, acoustically-perfect symphony venue, Music Hall. Finally, the long wait was over! To this then-hopelessly hooked Floyd fan, that year did feel something like an eternity. But I needn’t have feared. A PF tsunami – like the Hokusai waves painted on Nick Mason’s double-bass drum covers later that year – would soon be breaking hard.

Ads and news articles about PF soon started appearing in late Winter 1973 in national music publications such as Rolling Stone and Circus magazines. For example, a full-page ad ran in RS, featuring a series of progressive, wire-frame diagrams of the rainbow-and-prism graphic. Though in black-and-white, the ad was still iconic. Set amid generous white space were the band and album names, the graphics and a handful of tour dates. Tying it all together was a bold caption below the graphics that simply said, “A Superb New Album.” There was now no doubt that PF’s mysterious piece from 1972 had been finally committed to vinyl. And finally – a name: Dark Side of the Moon.

The Cincinnati concert fell on a Thursday night, within days of the album’s early March release. And while tuning in to Cincinnati’s FM rock-radio station a few days before, I’d stumbled into the middle of unmistakably ‘new’ Floyd. Thanks to the magic of archival recordings, I knew exactly what it was in seconds: The two-chord shuffle “Any Colour You Like.” True, I recognized it. Yet, at the same time, I’d never heard it like that. I needed to hear it again, of course, as well as the rest of the album!

That same station’s weekly show, Album of the Week, was a regular Monday night feature. So, hearing that DS would be aired that very week of the UC gig, I aimed to snag it on my reel-to-reel tape recorder at home. By flickering candlelight and the glow of my FM radio dial late that evening, I both recorded and absorbed the album. And – as with my recent chance first-exposure to the new “Colour” – the finished work seemed equally familiar and strange. For the first time since I’d discovered the Floyd in 1969, I was on shaky ground. I heard so many changes, not to mention a seemingly flatter sound than the more reverb-heavy mix typical of early PF shows. After all, my FM radio was only monophonic. Sure, that must have colored my perceptions. But this wasn’t simply a by-product of hearing a mono signal.

Lyrical songs were essentially the same, though multi-tracked and tricked out with special effects. Some songs were shortened, and familiar solos altered. But, most of all, the lengthier instrumental sections – my favorite parts, right? – had been radically changed or deleted. I also heard the addition of novel sounds to the Floyd canon — backing vocalists and saxophone. I wondered: Were my avant-garde art-rock heroes just rolling over for commercial radio? The dreaded sellout was an unforgivable sin for any band. Oh, no! Not the Floyd!

Although DS was never space-rock, even when it was still Eclipse (Remember what Waters said about that style in 1970?), flourishes of the old-school Floyd’s psychedelic DNA certainly remained. But – to my ears, at least – the recording seemed to have less spark and spontaneity. For the first time, it seemed that the Floyd I had known and loved so well had created a pop album!

When the night of the sold-out UC show finally arrived, I went in, fully expecting an electrifying performance in the typical Floydian ways – even in spite of Dark Side’s strange, new elements. The evening started promisingly enough with “Echoes.” (On the 1972 tour it had usually served as the second set closer.) Things then took a serious jam turn with extended, proggier versions of two tracks from Obscured. And then came an eye-singeing, brain-stunning set finale with the pyro-centric “Careful With That Axe, Eugene.”

While the Set I performance was indeed torrid, the sound quality was most un-Floyd-like in the cavernous, murky-sounding basketball arena. The instrumental balance was uneven, volume peaks threw distortion, plus more anomalies. It was almost as if the soundmen had cranked their ‘SUCK’ knobs all the way up. Yes, PF still had their famous 360-sound system. This one was larger, and custom-built for in larger venues. But – to my ears in the 20th row – the real culprit defeating the main PA was the deep slap-echo in the seemingly prehistoric concrete-and-steel auditorium. Fwiw, Joni Mitchell and Frank Zappa would both perform in this same space a few years ahead, and the sound experience at both shows was roughly the same to my ears.

It had seemed the biggest problem now facing the Floyd was in making their previously dynamic, nuanced live sound work in larger, non-theatre spaces. All of the new textures and some special effects were equally lost in the muck. Every band has surely encountered such tough rooms. And after a few rough minutes at the beginning of the show, the sound crews often sort them out, or at least minimize the most unpleasant effects. But on this night, gremlins lingered into Set II, which was the full performance of Dark Side.

For example, during solos in songs such as “Time” and “Money”, one could see but not clearly hear what David Gilmour was actually playing. (Mind you, I was on the main floor, straight back from him.) And from what you could hear of the vocals, the female backing singers on “Time” and “The Great Gig in the Sky” seemed to be straining. Quite possibly, they were struggling with a wonky stage monitor mix.

Production-wise, PF had also upped their visual game. As before, the main stage illumination came from three towers of solid-color lighting racks, generously flowing dry-ice fog, strobes, flash pots and secondary lighting. And there was an assortment of other new ‘eye-candy.’ But no films yet. One eye-catching innovation being used for the first time was a number of ruby-red lasers. These architectural shafts of light angled and moved about during the droning synth intro for Obscured’s title track and sections of the DS set.

Most notable of all the new effects, though, was a revolving, mirrored half-ball on the front of the extended center tower. The multi-purpose, mounted half-dome would reflect light in a brilliant sea of moving stars. More impressively – with the center darkened – a shroud of dry-ice fog could be ejected around its edges and backlit with brilliant light. This produced the stunning solar eclipse visual during the DS finale shown on the memorable fold-out poster that’s always been packaged with the LP.

If it seems this writer was just being peevish, one could assume it was just one disgruntled PF fan having a pout. But setting aside the structural and surface changes in DS, my belief at the time was that the DS performance really didn’t feel the same as in 1972. While the band seemed to play with abandon in the first set, the DS set had a feeling of tension and holding back. It was as if the musicians were now paying more attention to click tracks than to clicking with each other. From March 1973 onward, it had seemed that PF had entered a brave new world in their career. All of the exciting ‘R&D’ of 1972 had essentially been transformed into formula and ‘applied technology’. Experimentation was over – no turning back. The good news for Pink Floyd as a band, however, was that in spite of this rough early night, they were on their way to a very successful year.

Perfect Is As Perfect Does

As briefly touched on in Pt I of this retro visit to the Dark Side, the long incubation of the original composition took place not only through a year of ambitious touring but also in three extended recording sessions spanning some nine months. PF’s first concentrated session for DS started at London’s Abbey Road Studios, in late May 1972. A two-week session in France that spring had not yielded any DS tracks. That work-for-hire session had been dedicated only to composing the La Vallée movie score and polishing their Obscured album. But, if it means anything, the band did learn things from the ObC process which came in handy in the first DS session. And keyboardist Wright also started finding his way with synthesizers on some of the ObC tracks. So synths would soon make their first appearance on some DS tunes when PF got back on the road.

Songs that PF had already flagged as solid got committed to tape first that June, and more pre-production and road experimentation continued. After their 18-date Fall 1972 NA tour that included a now-legendary September gig at L.A.’s Hollywood Bowl, another round of recording and revision was on tap. Yet another slate of live dates in the late fall followed, this time in Europe, allowing more live fine-tuning of the arrangement. Then, in early 1973, it was back to the studio for a few last adjustments just before the fast-approaching March release. The last date in-house was February 9!

Perhaps from the band’s POV, the running order and arrangements had largely been nailed down. Yet, all of the changes surfacing on the final recording must have seemed critical in making a more compact and orderly artistic statement. (An essential lesson from the Obscured sessions.) Perfection was the goal, and the extended road testing was really like one big rehearsal. Among the goodies included in the Floyd’s official 2011 DSotM Immersion box set was a bonus disc containing live outtakes of three instrumental sections from the early DS. These castoffs – all from a June 1972 gig in Brighton, England – included “The Travel Sequence”, “The Mortality Sequence” and “Any Colour You Like.” Of course, the first two pieces had been replaced with the final sections we now know as “On the Run” and “The Great Gig in the Sky.” And “Colour” – originally a meandering scat-blues-jam that sometimes ran for more five minutes in 1972 shows – had been reimagined as a shorter, funkier synth-guitar vamp that carries right into “Brain Damage/Eclipse.”

Seemingly, the first early DS instrumental that PF might have had deep druthers about was “The Mortality Sequence.” Early on, this was not a song, as such, but more of a solemn organ processional by Wright. Layered over it was an audio montage of prayers and political speeches emanating from the quad system. As it turned out, that mournful passage resembled the outros on other PF songs from the late-‘60s. At one point, perhaps the band had thought it to be a clever performance-art piece. But bouncing “Gig” into its place suggests they knew the church thing was cooked and that inspired staging ‘moment’ would likely be lost in translation to tape.

When PF embarked on their 1972 Fall NA tour, the drastically reworked “Mortality” made its debut. The ‘funeral’ was gone. Now, the section – still in theory about the end of life – featured a new Wright piano/organ composition with chord sequences that remained in the final “Gig” recording. The mid-section in this version then included a noisy synth solo over a rather demonic-sounding ascending scale. (Wright had not used synths live before Fall 1972, so this was a new experiment. Interesting but temporary.)

Radical change also came to “The Travel Sequence.” Although not space-rock as such, this instrumental passage – a survivor through the year – was a charging jazz-rock fusion jam with a heavy guitar delay. As archival recordings of the piece show over time, fitting this more choppy groove into the flow between “Breathe” and “Time” could be shaky at times. Where “Travel” used to have an ambient bridge to the next song, PF moved to using a power-chord end-tag and a volley of chiming clocks to signal the transition to “Time.” Maybe that was more entertaining in a live rock show, anyway, but the rawked-up ending of “Travel” seemed even less seamless.

Many more decisions that led to Dark Side’s ‘classic’ sound seemed to have come just before release. According to some sources, much internal debate concerned whether to use a “dry” sonic mix to make effects more three-dimensional or a “wetter” mix that preserved more of the band’s resonant live sound. Consensus was reached, and crisis averted. Reportedly, the compromise had come down slightly in favor of the “wet” one.

As if the Floyd didn’t already have enough to do, they rolled off tour and right into another short side project at the end of 1972. This was to provide live backing for a series of French ballet performances for a few weeks in Paris. But, even for some dates, the band was too pressed to make some gigs, so they provided a pre-recorded soundtrack.

Commitment fulfilled, they and their esteemed engineer Alan Parsons convened in the studio one more time for the final push to get everything just right with DS. Even with most basic tracks and lead vocals complete, a number of songs would undergo a last buff, largely with addition of backing vocals and saxophone. But a couple of sections still nagged at them. Coincidentally, this was also the time in which filmmaker Adrian Maben had visited the studio to document the band in crunch mode. The French director had famously filmed the Floyd performing en plein air in a Roman amphitheater in Italy, in October 1971, for his art film Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii. (At that time, the DS concept had just about started to be a glimmer in PF’s collective minds.) However, Maben – who had only included live-performance footage in his first version – was unsatisfied with the movie’s one-hour run time. He requested a chance to document PF as they worked in the studio and to add interviews to round his film out to a true feature length. Maybe even add a full performance or two.

Session clips seen in Pompeii show PF working on such songs as “Us and Them”, “Brain Damage” and “On the Run.” In particular, for “Run”, we see Waters programming and recording a section of that yet-unheard electronic passage. Using the sequencer on a revolutionary new suitcase synthesizer, Waters keys in series of notes, then speeds it up. This gave a sneak peek – after the fact – at what was soon to come. It was, “Hello, Synthi AKS – Goodbye, ‘Travel Sequence’.” (Fwiw, clips of the other songs may not have been actual work but staged for the benefit of the camera, since those songs had reportedly been recorded months before.)

Perhaps the most crucial unfilmed adjustment in this final session – merely weeks from DS’s March release – was the completion of “The Great Gig in the Sky.” This piece, which anchors the end of DS’s first half and for many is the emotional high point of the album, had evidently evolved the most. “Gig” of course had begun its life as keyboardist Wright’s organ piece in “Mortality.” And then a reworked version debuted on the Fall 1972 NA tour. Clearly, he had been moving toward something more emotional and dynamic but wasn’t quite there yet.

In early winter 1973, as the final mix was nearing completion, Wright had modified the mid-section again. He dropped that interim synth part and introduced an alternating, two-chord keyboard interval. Engineer Alan Parsons had felt it still needed something else. So he added a new trial layer to the mid-section as he compiled a new demo mix. Over that shuffling interval, Parsons inserted just-released audio of NASA’s Apollo 17 astronauts transmitting from the Moon on their final mission, in December 1972. (This full DS mix was preserved on a bonus disc in the 2011 DSotM Immersion box set.) Although interesting to hear, it clearly wasn’t the crowning touch PF and their engineer were seeking.

But Mr. Parsons – being the resourceful guy that he is – had one more trick in his watch pocket. He and the band had a collective hunch to try Wright’s new arrangement with vocals. Parsons had known of a session vocalist in London named Clare Torry. Indeed, she received a call, and a time was booked for January 21. Even with this step, the band still had no clear idea of exactly what she might bring to the piece. As the singer has told it herself, PF members and Parsons greeted her and asked her to start vocalizing, without words. At this, she says, she was inspired to use her voice “as an instrument.” So, it was three takes total, all improvised over the pre-recorded section. Afterward, all the crew had said to Torry then was a simple “thank you.”

After collecting her session fee, the singer left the studio with no expectations. Nonetheless, her efforts were used, edited into a glorious vocal sequence over Wright’s heartfelt, multi-keyboard section. Thankfully, Dark Side could then finally be put to bed. And that’s just some of the perfectionism that made all the difference in saving the Floyd from permanent cult status.

Crushed by Numbers

Confession time: I didn’t buy my first copy of DSotM until 1975, the year in which I turned 21 and could afford my first apartment and a proper stereo. I’d bought a first handful of albums to break in my new system, and DS was first out of the wrap.Of course, by this time, I’d only begun to gain knowledge about all of PF’s back-end work on DS. Within that last calendar year, I’d seen their acclaimed Pompeii movie several times, and, I must say, the studio segments opened my eyes – and ears. And though I’d heard DS in stereo many times at friends’ houses and in cars, there was nothing like hearing it on my own system.

Now that I was able to cast off my preconceived notions about DS and why PF had made various choices, I finally felt ready for it. And it sounded great! And I could play it as much or as loud as I wanted – no parents haranguing me about the ‘strange sounds’ coming from my room. Now that I’d learned a thing or two about how PF had labored so long and hard on it, I began to hear DS with my ‘third ear’, not filtered through my personal music-snob bubble. Clearly, PF had actually done everything right. And, anyway, can 45 million Floyd fans really be wrong? Right out of the box, the rock music listening public took Dark Side into their hearts with unequalled enthusiasm, except possibly for the early days of Beatlemania. Within two months DS hit the Billboard Top 200 chart, its home for a record 741weeks. In later years, it even returned to the chart after Billboard changed its requirements to allow older releases to be counted.

In 1973, the band committed itself fully to the album’s promotion, even booking North American dates close on the heels of its release. A barn-burning spring tour of about 20 dates was the first push, before a short London run in May. Soon, they would prep for another NA leg in June and July. The launch strategy paid off handsomely. And the record company ‘goosed’ that goose to get more golden eggs. With the summer tour looming ahead, PF’s U.S. label, Capitol Records, next released a pair of singles – an unused strategy since PF’s early post-Syd Barrett years. The first of these singles – containing the song “Money”– soon began burning up both AM and FM radio. It became a Top 20 hit.

The single’s killer buzz, of course, insured a surge in record and ticket sales. And, in the proverbial eye wink, “Money” and Floyd had become synonymous. Ironic, isn’t it? Such a satirical, anti-materialistic song became the ‘secret sauce’ that gave the band their long-dreamed-of success. As the year progressed, ticket demand spiked, and the second NA leg in Summer 1973 saw the band scaling up from 8,000-seat arenas to higher-capacity outdoor ‘shed’ venues. PF had already doubled capacities from 1972 to 1973, and now the explosive audience growth — sometimes tripling or quadrupling – had come in only the space of a few months.

I did attend a second show on June 24, at Blossom Music Center, in Greater Cleveland. It was my first experience of seeing PF in a bulging, general-admission lawn setting – and from far back on the lawn this time! Reportedly, it had a capacity audience of 32,000. And I believe it. It took more than two hours to get out of the parking lot afterward! And my retrograde motion – which, oddly, was taking this loyal fan further from the stage each time – seemed to be accelerating! Yes, audiences were simply mad for The Moon!

Touring continued, with new DS shows in the U.K. and Europe later that year, but then the band rounded for home and some much-deserved downtime in the first half of 1974. Over the summer, PF returned to the stage for a short, warm-up run in France. They spotlighted a couple of new songs, a few old proggy Floyd classics, and the full Moon in Set II again. That was more than two years of DS being served as a main course. During early 1974, as PF had been slightly less active and the punk-rock movement had begun to take hold among younger music fans, the perception grew that PF had maybe become too big and bloated. Maybe even not cool anymore. In short, dinosaurs.

When PF performed a complete set of new songs and DSotM in concerts in the U.K. in Fall 1974, the BBC recorded one November concert, at London’s Wembley Arena. This run of shows had generated some mixed reviews, again underscoring the POV that, perhaps, the band had begun to lose its Midas Touch. Critics reporting on the performances dismissed them as uneven, contrived and bordering on predictable. One critic even griped about the band’s physical appearance. (This recording of DSotM is included in the 2011 DS Immersion box and will be also be included in the new 50th anniversary deluxe DS box set, coming out in early March 2023. So fans can decide for themselves.)

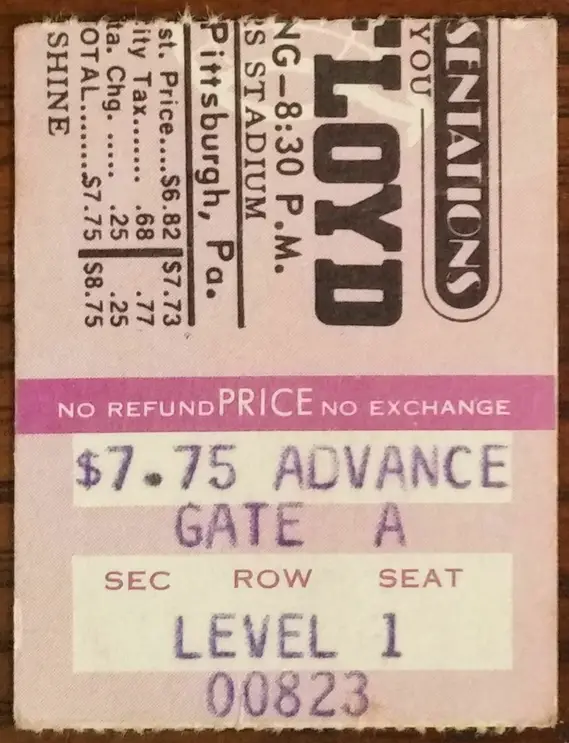

Shortly after I’d made my long overdue purchase of DS, a full-page newspaper ad in the Cincinnati Sunday newspaper announced a new PF concert in June. Yaaay! It would be at Pittsburgh, however, at Three Rivers Stadium. And it was billed as the only regional show. Boooooo! Nonetheless, a road trip would certainly be on my horizon. No one had known for sure what PF would be performing, but, no surprise, Dark Side was once again the centerpiece. And ticket demand this time around had doubled again, now closer to the 50,000 range and selling out rapidly. Quite likely, this was due to the pent-up demand of PF not having toured the U.S. for close to two years, and to more limited, large-scale shows. Prices were going up, too.

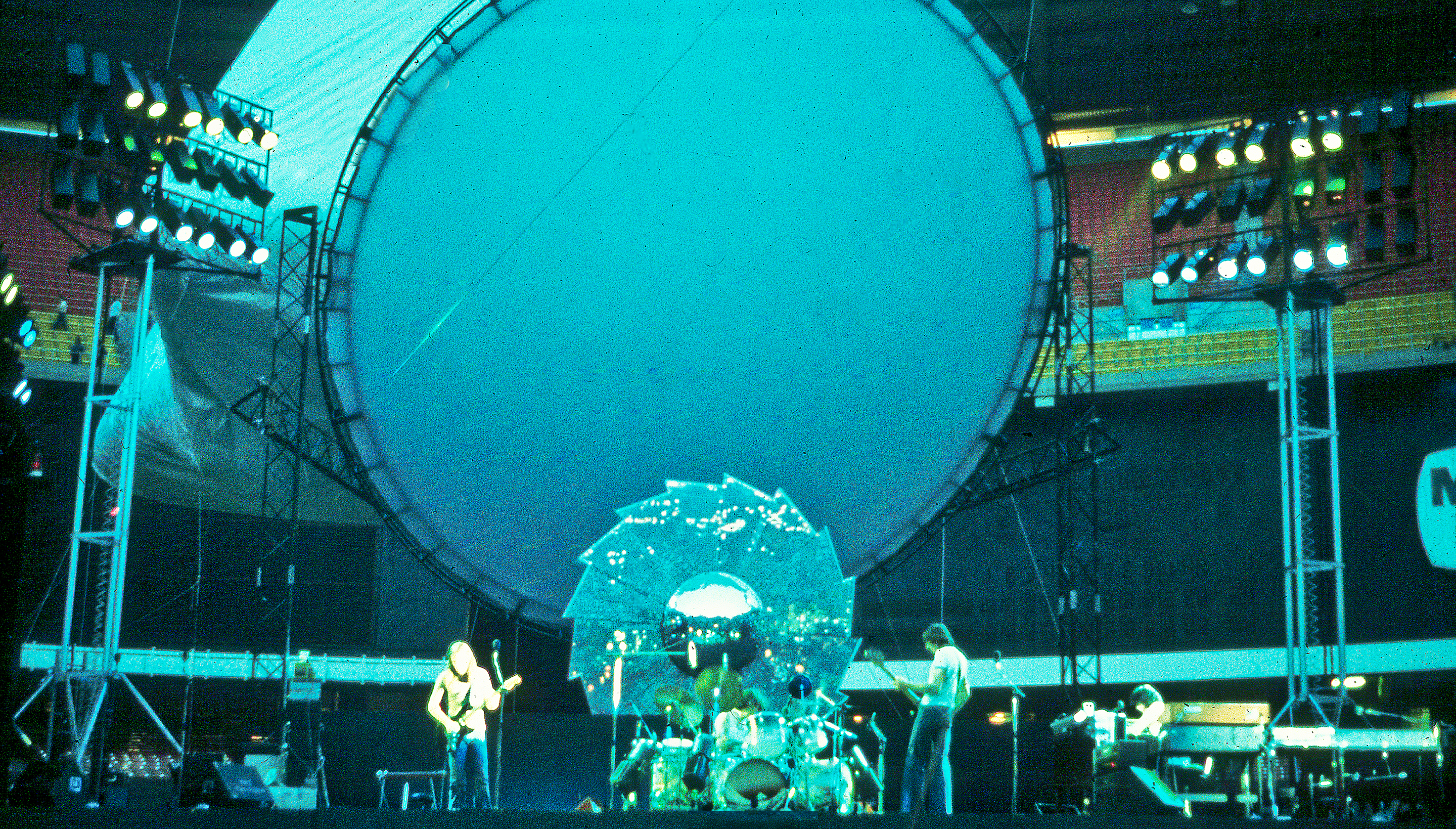

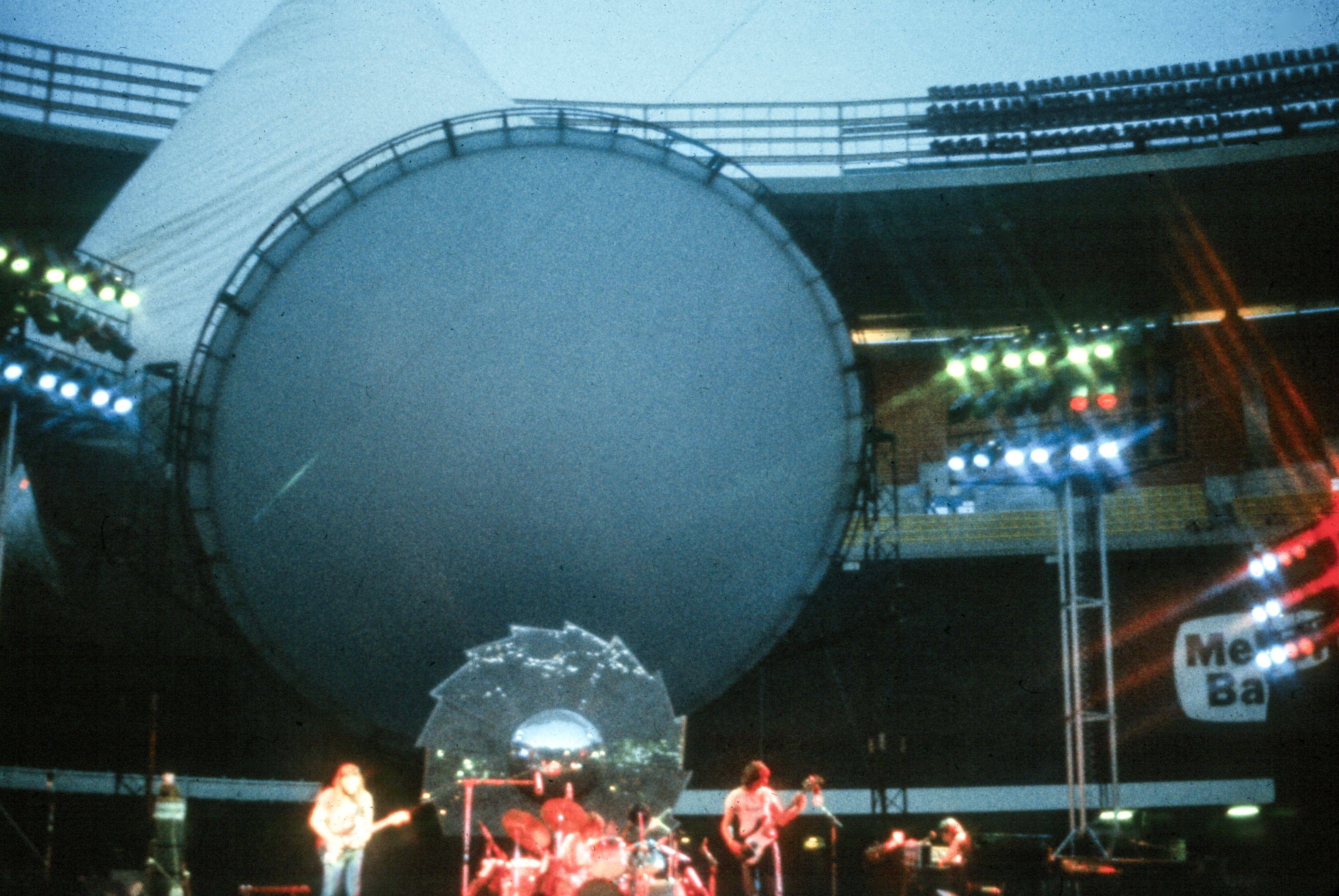

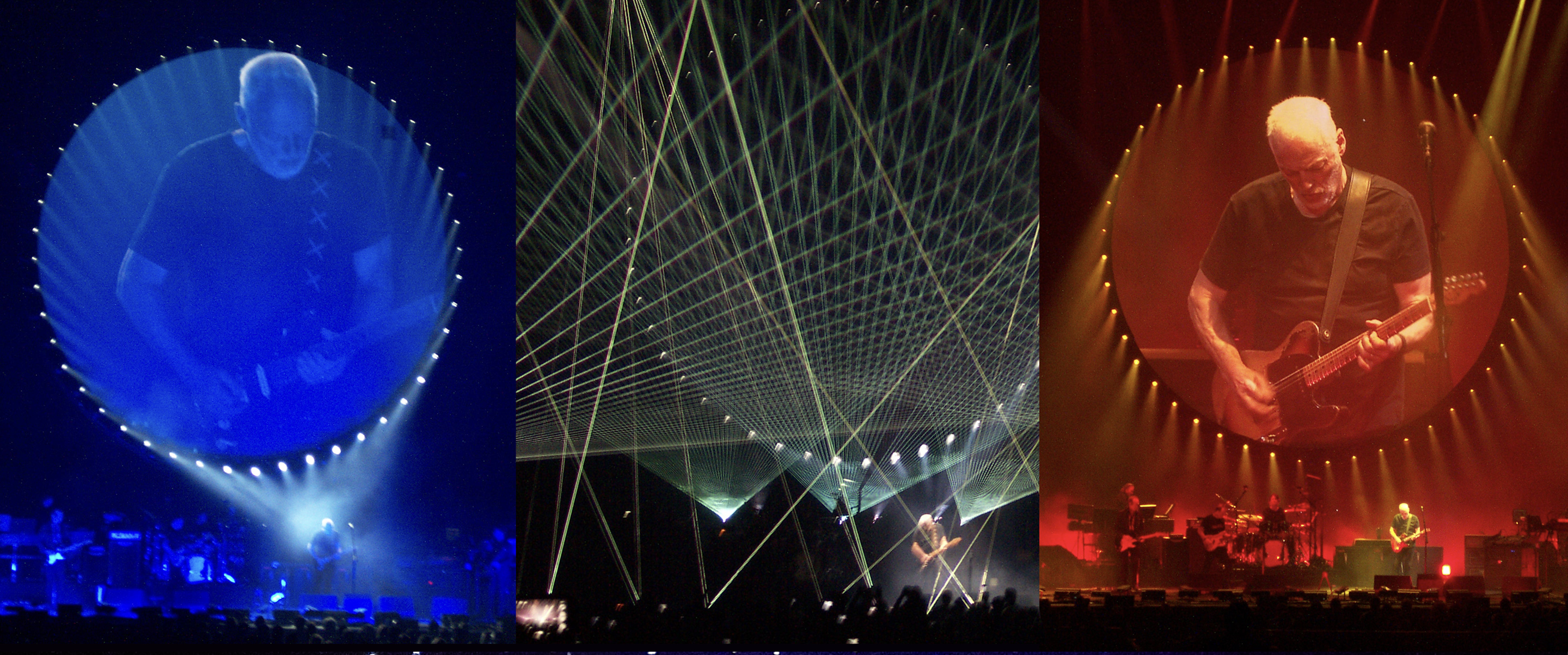

I was just as eager as any fan to join the circus, and join I did. My late friend Joe – another ‘first generation’ PF fan who was determined to take photos – made the nearly-five hour drive with me and some extra passengers, from Cincinnati to Pittsburgh. (Some of his photos from the show accompany this article.) As literal survivors of that show on June 20, 1975, we could see and hear that PF had made a full, clean break from their storied past as an ‘underground’ band, both in repertoire and stagecraft. The new show boasted another whole new set of songs in the first half, a full Dark Side performance in Set II and only one encore – a full 22-minute version of “Echoes.” That was quite literally the last holdover from PF’s halcyon daze!

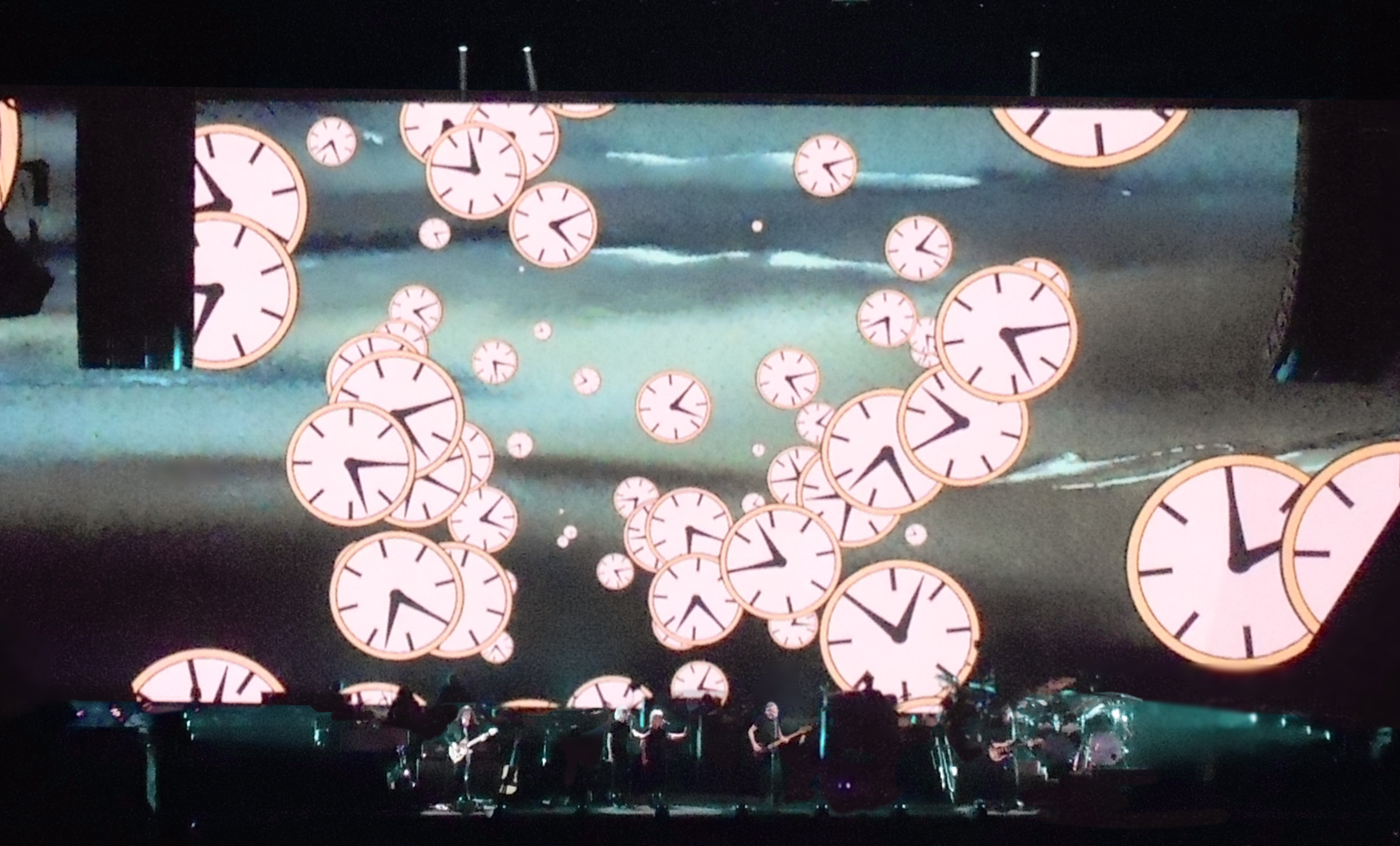

The band had also ramped up their production game again, introducing the circular rear-projection screen – nicknamed “Mr. Screen” within the band’s inner circle. This was for projecting special films that illustrated the themes of key Dark Side songs for the massive audience. These included the famous animated ‘sea of clocks’ for “Time”, the quick-cut montage of materialism gone mad and the record-factory assembly line for “Money”, and – of course – the montage of all the world’s lunatics of the 1970s, set to the tune of “Brain Damage.” They also added a new array of stage lighting, a scale-model plane that would crash in a fiery explosion at the end of “On the Run” and – early in the tour – even a giant, inflatable white pyramid that would hover over the stage during the DS set. (This is visible in another photo with this article.) Heh – maybe that’s where some critics had gotten the idea that PF had grown a wee bit too Spinal Tap for their tastes.

If the jump from the 3,000 to 8,000 seats – and upwards – in 1973 was hard on the band or even some fans, imagine being suddenly in a near-50,000-capacity general admission show in mid-summer, when the temps had been baking hot all day. At the Pittsburgh show, gathered fans were let in the late afternoon, and then the most motivated of us made mad dashes towards the center-field stage to stake out space on the large, plywood planks spread all over the field. The stands filled rapidly, too. Tempers simmered until the 7:30 showtime, when the band launched into Set I, still in daylight. Tensions mounted and many ‘words’ flew with increased crowding and pushing – which had started even as the field filled out. It bubbled over into open anger when people nearest the stage insisted on standing during the performance.

PO’d fans on the field felt these inconsiderate, um, folks could have easily sat down and let everyone behind them enjoy the highly visual show. But this was the era of Saturday Night Fever and a wide range of recreational drugs. So, many had come lubricated or altered – and had gotten even more so during pre-show – and were ready to dance. And to set off firecrackers. And, yes, even to fight. (At a Floyd concert? Really? ) My friend Joe and I - both early Floyd adopters and purists about ‘these things’ – really felt we were the ones on the ‘dark side’ now. But no one was going tell them what to do – nuh-uh.. This was a partay, maaann! “WOOOOO! PLAY MONNNEY!!!”

Needless to say, there were more shout-outs for a song called “SIT DOWN– SIT! DOWN!!!” than there were even for “Money.” We wanted this other song, too. (You might hear us on a YouTube clip of the show.) On archival Canadian concert recordings, you can even hear voices screaming out for this same song, only in French: “Asseyez-Vous! ASSEYEZ-VOUS!!!”. But the Floyd didn’t play either version.

Just as when I had seen PF audience sizes expanding exponentially – like some recursive virus – in 1973, I was asking the very same questions: Who were these people? Where did they come from? And why are there SO many of them? There’s a good chance that the band was even asking those same questions. At the time, it was unmistakable that Waters had taken deep offense to the audiences’ toxic self-centeredness. It seemed to distract and annoy the whole band, resulting in noticeably choppy performances. Early in the tour, he attempted only indirect remarks, and then he dropped all pretenses after that approach failed miserably.

Before a song introduction in Set I at Pittsburgh, Waters had to shout above the crowd noise, “David starts this one on his own. . .so you’ll have to be A LITTLE BIT QUIETER!” At another show soon after, in Hamilton, Ontario, he turned up his passive-aggression dial. “Okay! Tell you what. . ., “ Waters said bitterly. “You just go on talking amongst yourselves and we’ll try to carry on.” And, finally, at this same show, when introducing the shiny-new song “Shine On, You Crazy Diamond”, he slipped in a zinger that likely didn’t even register with most of that crowd: “Um, ahemmm,” he said, clearing his throat. “This is . . . um, a song. . . about not being here. . . .” Ouch!

In time, Waters would become fed up with this industrial-grade indifference and come to believe that an invisible wall had grown between the band and their audiences. In retrospect, we now know this gave partial inspiration to the Animals concept. And The Wall? Well, the live stagings of that were a literal, physical erection of Waters’ discontent with stadium audiences. And though the post-Waters, three-man version of Floyd did revive the full DS as part of their Division Bell tour in mid-1994, Waters would never perform the whole of DSotM with PF again after 1975.

Waking the Lumbering Beast

Over the course of the Floyd’s next four studio albums, a fault line that had been edging ever wider since the early days of DS had split wide open. The driving force was the long-smoldering animosity between Waters and the rest of the band. By consensus of the band’s team with Waters leading the charge, keyboardist Wright lost his position as a full member during the making of The Wall. Then, in 1985 – after the obvious non-starter of The Final Cut had trailed off completely, Waters bluntly notified Gilmour and Mason that he, too, was out.

The collision course that Waters had been on with audiences had bled over into his working relationship with his bandmates, and after building that incomparable Wall largely together, the band had The Great Falling Out. In 1985, Waters famously went public with an announcement in which he tagged the band as a “spent force creatively.” Fans might have worried whether they’d hear any Floyd music – much less Dark Side – ever played live again (“Hello, tribute bands. . . .”). But both Gilmour and Waters both jumped quickly into solo albums and tours. And, indeed, a good amount of PF music – even DS songs – was played on those two 1984 tours. But the erstwhile Floyd guitarist was a quick study on the awful truth: He had zero name recognition as a solo artist, and he calculated that it would be a hard slog. So Gilmour’s smooth move then was to try to reanimate the “lumbering beast.”

Out of his desire to reinvest in the established Floyd name instead of starting over from scratch, Gilmour – along with Wright and Mason – took the world by storm with an unexpected new album, and associated tours in 1987 and 1988. This was A Momentary Lapse of Reason, an album that entered the public’s imagination with the support of high-rotation videos on MTV and an ambitious slate of successful stadium and arena shows. And an awful lot of Dark Side music was played on those tours, too.

Waters, for his part, released a second solo album in this same period but never caught the kind of rad success that came in full connection with the Floyd ‘brand’. At the time, the name recognition of the man who had authored all of Dark Side’s lyrics had turned out to be no more King Midas than had Gilmour’s. Famously, Waters – who was said to have played re-interpreted PF material that included DS songs on his 1987 tour – had found himself playing to only half-empty arenas while the PF guys were selling out multi-night runs. He had called it a “character-forming experience.”

Waters’ solution? File a cease-and-desist lawsuit to stop them from using the band’s name. He had taken the view that he had been the sole creative energy in PF and the rest weren’t even contenders. But, as luck would have it, Waters lost his suit. And the Floyd kept shining on. Nick Mason, being somewhat bemused by it all, couldn’t help but make a cheeky remark about PF’s unexpected second life in the run up to the millennium. “You don't want the world populated only with dinosaurs,” he said in an interview at the time, “but it's a terribly good thing to keep some of them alive.”

In the late 1990s, when Waters returned to the touring circuit after a very long hiatus, he seemed at first a changed man, seemingly touched by the generosity and love coming from audiences in his suddenly-sold-out shows. (The only time he had surfaced in a high-profile way in twelve years was a one-off, 1990 benefit performance of The Wall, in Berlin, with celebrity musical guests.) New generations of fans who knew nothing of the band’s vicious infighting were re-discovering the Floyd with fresh ears and open minds. And, in fact, Dark Side would often be the gateway album for many new PF fans. From the stage and in interviews during his 1999 rebound, Waters would often remark that he could “feel the love” he thought had died so many years ago, “crushed by the numbers.” Ironically enough, that flattening weight that Waters had personally brought upon himself – and the band – had come from their having put so much energy into crafting The perfect album. Yes, Pink Floyd had finally ‘cracked it’ in 1973 with Dark Side. But, in hindsight, it’s now clear that Dark Side had also cracked the band.

A Heart Beats Through It

Although they had reintroduced Dark Side as a full concert feature again during the second half of their 1994 Division Bell tour, the three ancient mariners of Floyd quietly sailed away from the sea of faces after that tour. They were no longer in search of what Waters had once derided in a song lyric as “more and more applause.” (The second half of the 1994 tour was the first time audiences had been able to hear PF play the full DSotM in nearly 20 years. It would also be the last.) And though they have since managed the occasional solo tour on a relatively smaller scale, the touring days of Pink Floyd had become very much like Monty Python’s infamous dead parrot.

So, in the midst of prepping for a new solo album and a small supporting tour with bandmate Wright in June 2005, guitarist Gilmour received a surprise invitation. This was to reunite with his former bandmates – Waters included – on stage for a higher purpose. This one-off event still involved more applause and money, but this time it was to donate their performance to the fight against world poverty at the mega-charity concert Live 8, in London’s historic Hyde Park. This was some big-time, do-goody-good bullshit, all right.

Now, after all of the bad blood that had been spilled between Waters and his former partners over time, this ‘sort of homecoming’ allowed them to step outside of themselves and bury some axes. And they could be heroes again, just for one night. Who’da thunk it, right? But there they were, delivering a stunning, five-song mini concert that included three songs from Dark Side, plus one each from Wish You Were Here and The Wall. Given the nature of the event and the fact that one song had come to represent the best of DS so well, is it really any surprise that “Money” would make the short list again?

There was still magic in the old Moon that night at Live 8, as the sound of Dark Side’s signature opening heartbeat arose on the PA with a vintage, 1977 film backdrop of a friendly, airborne piggy in flight during the prelude, “Speak to Me.” Surely there was a universal moment of disbelief – and probably not a single Floyd fan who saw it whose eyes stayed dry the whole time – when the band once again plunged into the opening chords of “Breathe.” It proved for the record that – through all this time – a loud, insistent heart has been beating through it all.

In spite of the many “glittering prizes” that were said to have been dangled in front of the band, Gilmour remained steadfast in his view that there would be no future Floyd tours, not then nor ever. He further made it clear that he was simply content – every ten years or so – to do a bit of “an old man’s tour” that would not involve waking that gnarly old “beast” again. He has still featured a few much-loved DS fan favorites in his solo shows but has also worked in Barrett covers – and even a Wright song when it has made sense – to honor those two now-long-departed former PF members.

In 2006, the now-late keyboardist joined Gilmour for one of those short-run “old man’s tours”, held in a few small select-theatre locations. There would be no more feeding of the gaping maw of the insatiable stadium crowds of yesteryear for Messrs. Gilmour and Wright. In retrospect, we now see that it proved to be Wright’s last tour as a bandmate to Gilmour, since, sadly, the keyboardist died of cancer in 2008. It was such a special time for the two longtime musical partners, who would once again perform their first masterpiece “Echoes” – the timeless PF song that had taught the band how to really write, work and play as one. And those performances were magical, too, for the smaller audiences who truly appreciated every note and echo of it.

Not one ever to be upstaged, Waters himself turned once more to The Dark Side in 2006 and 2007. With DS as the main attraction, he embarked on a two-year world tour which not only took him to the usual continents but also to lesser-traveled regions that included China, India, New Zealand, South America and Russia. The experience of playing again with his estranged PF bandmates and receiving all the instant audience karma at Live 8 had obviously spurred him into action. This gave him a few more rounds of ‘applause’ for the piece he had done so much to bring to life. And it should be noted that – like any established PF tribute production of the last 30 years – he and his merry band of session players pretty much played DSotM as straight-from-the-album and down-to-the-minute as possible.

The full story of The Dark Side of the Moon has not been written yet – and perhaps it never will. It seems to have a life and a mind of its own. Every generation seems to discover it anew and to find new ways – for example, elaborate tribute tours, deluxe laser shows, even synching it with the movie The Wizard of Oz – in which to enjoy it.

This special two-part report on gratefulweb.com has only been one lifelong PF fan’s attempt to bring some kind of order to the unruly history and memories of this landmark composition’s creation. And thanks to the stalwart PF-themed bands who will be touring this year to celebrate this important anniversary, Floyd fans of every stripe will soon be able to have an up-close and personal live experience with this certifiably-mad masterpiece. (Pro tip: If you plan to see Nick Mason’s Saucerful of Secrets tour in Europe this summer, remember that his band’s PF repertoire ends in the early ‘70s with Obscured by Clouds.)

It has always been one thing to listen to the recorded version of DS – on the album, through headphones, on an eight-track car player or even on a mono reel-to-reel recorder late at night. Your mileage may vary. But there’s no substitute for being there to hear a live performance of The Dark Side of the Moon, faithfully and passionately performed by musicians who truly understand its deeper, inner workings. I still remember my first Moon, and I’m still chasing its eternal shadows and light.

This article is: “Dead-icated to the memory of Joseph Stercz, of Cincinnati, Ohio, a true fellow Floydian traveler who loved his Floyd as Pink as possible. And who inspired me to capture musical moments with my camera and my mind.”

Additional: Dark Side will be honored in a brand-new book to be released in April 2023. A new luxury box set containing a re-release of the album together with numerous related music items and formats is also said to be on schedule for release at the same time. This information will be updated when exact dates are available. And keep your eyes open for the schedules of your favorite PF tribute bands, as announcements are coming weekly now about special Dark Side-themed tours.