The year is 2005. Bob Weir and RatDog are playing the Fillmore Auditorium in Denver, Colorado. I was born in 1969. The Grateful Dead were four years old and gathering steam for their unexpected journey through time that would bring them 40 years into the future. They would become separate bands with separate energies, separate missions. Yet the train keeps rolling, borne of its own momentum, the adoration for the songs of the Grateful Dead, the adoration for the members of the Grateful Dead, the sense of community that will not die, adding new members even as the old ones fade away. The music, always the bedrock of the Grateful Dead, keeps broadcasting into the future, even as it grows and changes, a signal in the noise emanating from 1965, 1967, 1976, a history lesson of American culture from the increasingly tumultuous decades of our current era.

The Fillmore Auditorium in Denver is now the only other Fillmore theater. In its original incarnation as the Mammoth Events Center, it hosted shows in the sixties that many say changed the character of the Colfax Avenue neighborhood into the seedy strip it is today. Extending 26 miles from the foothills to the plains, Colfax Avenue is one of the longest streets in the country, with the Fillmore nestled almost at the center, near the state capitol. With a mix of adult bookstores, dives, low rent motels and street corner hustlers scattered among the still renewing community, Colfax is the perfect real world evocation of Shakedown Street, which was first performed by the Grateful Dead on August 31, 1978 very close to the western end of Colfax Avenue, at Red Rocks Amphitheatre, and unsurprisingly opened RatDog's first ever appearance, Friday night at the venue.

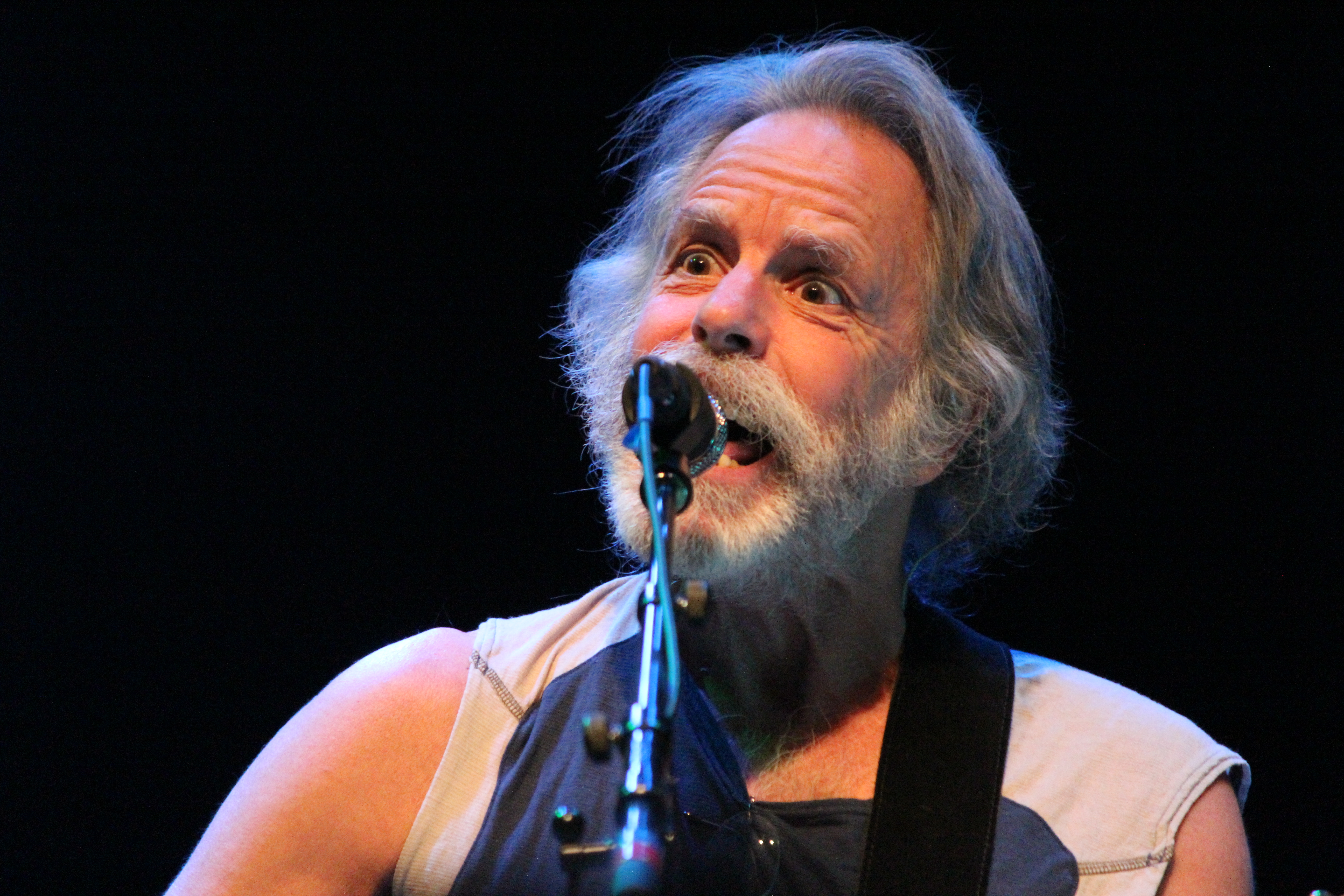

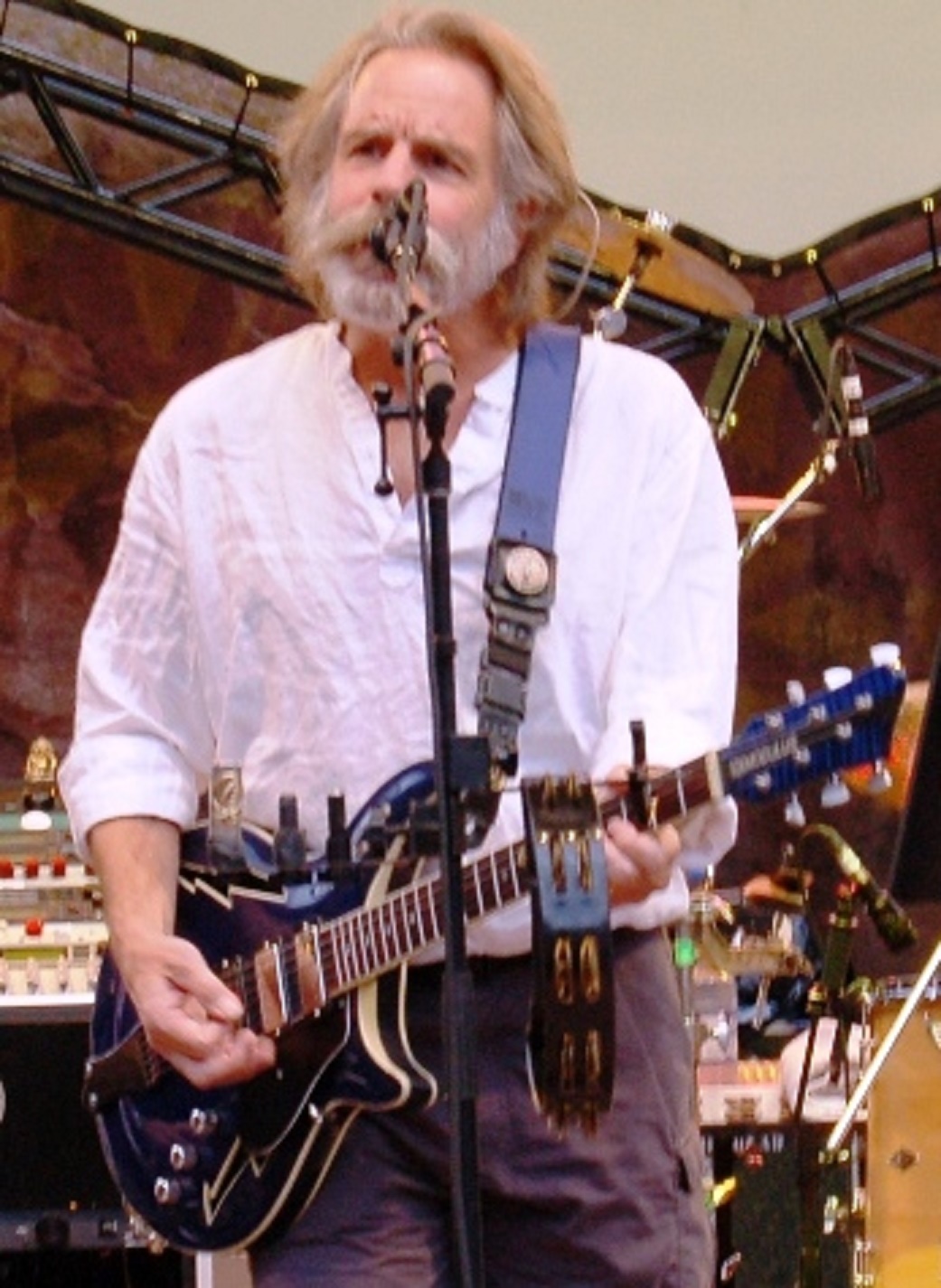

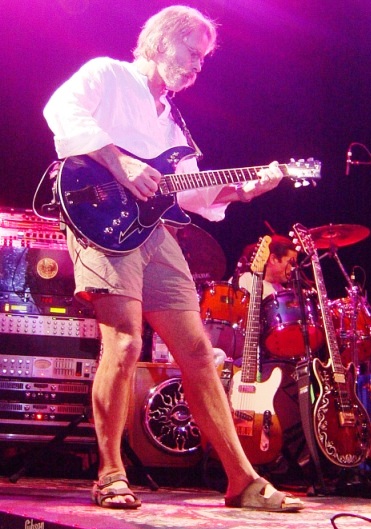

As the crowd jumps to the familiar tune, now having opened 4 of the 15 shows performed at the Fillmore by either Phil Lesh or Bob Weir, Weir is onstage with RatDog and the band's most stable lineup since its inception - guitarist Mark Karan, bassist Robin Sylvester, keyboardist Jeff Chimenti, drummer Jay Lane and saxophonist Kenny Brooks - dressed in shorts and sandals despite the December chill, beard neatly trimmed, sporting a pair of distinguished looking specs, leaning into the microphone with that unmistakable pose and singing with that unmistakable voice that hasn't changed a bit since 1965. With all that has happened over the last 40 years and all the critical and uncritical dissection of the Grateful Dead, it is most frequently Weir's crystal-clear voice that gets ignored. While he is unmistakably a talented guitarist and musician, Weir's voice remains to this day his best and most evocative instrument. After following Shakedown with a skillful but perfunctory performance of Minglewood, that leaves me thinking a little bit of the old Saturday Night Live band, Weir leaps into one of his most soulful covers, Dylan's She Belongs to Me, and is clearly in good form as one of the world's best Dylan interpreters.

The year is 2005. The rules are changing. The Grateful Dead blossomed into a full-blown world-wide phenomenon as a dedicated army of amateur producers began distributing recordings that they had made of the Grateful Dead's concerts, with the bands blessing, many even plugging directly into soundboard. The cassettes changed hands via networks of fans connected by newsletter, by word of mouth. Blanks were sent in bulk to complete strangers, who would take time to duplicate over and over and over again shows requested by complete strangers, only for reason of their love of the band and the community and their willingness to participate, to keep the fire burning. The band grew up, the band's support staff grew up. Marriage, kids, responsibility, family, illness, life and death. When Jerry passed on, the great engine that powered the train was no more - the singularity of the Dead Show. All that was left behind of these shows began to increase in preciousness. Beginning almost simultaneously, the growth of the internet completely changed the accessibility to the music being traded.

Chuck Morris, the well-known local music promoter, whose organization is now part of Clear Channel, is onstage introducing the band's long awaited first Fillmore appearance and announcing that CDs of the show will be available immediately after the concert. There is a still a group of tapers gathered by the soundboard producing the audience tapes that many fans still prefer over the perfection of the digital soundboard recording, but modern technology and economics have created the market for the instant digital replay. To the band whose job and passion is to create music night after night, a different performance each time, some better than others, the facts of this modern age must be both amazing and disturbing. While the Grateful Dead invented the feedback loop between the audience and the band, now fans will yell and scream their names into the performance with the hope of being embedded in the recording for posterity, and not for any particular kind of emotional involvement other than bragging rights. Still, the market exists, is fulfilled and mouths are fed.

After the Dylan cover, Weir steps into another Garcia classic, Row Jimmy. In the highly opinionated Grateful Dead universe, some consider it sacrilegious for Weir to play Garcia tunes. For some songs I tend to agree. Row Jimmy is not one. Never my favorite Dead tune, RatDog performs it as well as any band and I sense an energy, a seriousness of performance from Weir that I haven't seen for a while. The rest of the first set is fairly bluesy. Boots plays harmonica on Walking Blues and Boss Man, The band plays one of their own, Lucky Enough, and knocks out a Big Railroad Blues to close it down.

The year is 2005. No one is certain about anything anymore. An entire generation does not recognize life without the Internet. Everything in life can be had online. Many kids today may never buy a CD in a record store. Perfect copies of any form of entertainment may be easily made available to friends and strangers. And a perfect copy is always perfect no matter how many generations from the original have passed. As Bob's lyricist and old friend John Perry Barlow has argued, with the advent of the Internet not only is the genie out of the bottle, but the bottle has now ceased to exist. Those dedicated tapers and tape traders now have the perfect distribution medium. No more long sessions laboriously creating and mailing cassettes to complete strangers. SASE is a dead "word", almost absent from the lexicon. I can find just about any show I want in a myriad of versions, both audience and soundboard, from numerous websites and sharing mediums, most of which are administered by people with highly ethical ideals about the distribution of the Grateful Dead's music, always following the guidelines set forth by the band and refusing to share any material that overlaps with an official release. Because of the ease of distribution, I have not added any new Dead shows to my collection in a few years because all of my hard drives are full and I have been lax about archiving to CD.

There are no more Dead shows. All that is left are the countless copies of lovingly created archives, analog and digital, soundboard and microphone, released and unreleased. To this date, the Grateful Dead have distributed more than 50 official releases of complete or partial shows from their archives. Every time one of these shows is released, most operators of sharing networks or sites will remove from distribution soundboard versions of these shows, in deference to the wishes of the band. There are no more Dead shows. The fans have always owned the live music, which as an unintentional consequence created an entirely new marketing paradigm, which thousands of organizations both entertainment and otherwise have attempted to emulate. Now as the band tries to enforce some order on the digital chaos, they have come under fire for shifting the paradigm, for trying to somehow contain the last resources they have left. Old feuds are rekindled, compromises are reached. Old pal Barlow advises old pal Weir of the futility of the whole thing. Fans are not amused. The status quo is maintained, barely. There are no more Dead shows. All that remains are the copies - and the continuing performances of the surviving members.

Bob Weir was born to sing El Paso. Where Marty Robbins wrote and performed it with the ultimate singing cowboy smoothness, Bobby delivers it with his Saturday night tequila confidence that permanently replaces any other rendition, even for the casual listener. The band takes the stage to play the song to open the second set with their acoustics out but switch to electric as they perform Masters of War and Corrina segueing into West LA Fadeaway. West LA is another Jerry tune that Weir performs exceptionally well, a slight hint of reggae in his guitar, his singing sinister and sensuous at the same time. Next up is the mashup of Silvio, Tequila and Iko first unveiled on April Fools Day in Chicago, which is both clever and silly at the same time, with the members of the band following up with a series of solos before moving toward the conclusion of the set, beginning with Sugaree. Bob Weir singing Sugaree is not right, shouldn't happen. Too much of a signature Garcia tune. However, Ratdog's version is strong, especially toward the finale, where an extra bit of jam from the band gets the crowd rocking right into an outstanding St. Stephen/Eleven closer. The Ripple encore is merely standard but the band and audience seem fulfilled as RatDog takes its bows at the conclusion of their first Fillmore appearance.

The year is 2005. There are no more Dead shows. Bobby is still out there carrying on with RatDog playing Grateful Dead songs, some RatDog songs and a generous mix of covers. The fans still come out to see him and he is, after all these years, still the rock star of the band. When he approaches the microphone with that half-step forward, leans in and starts singing with that distinctive voice, a small part of the Grateful Dead remains.